Fig. 66.1

King Aha Slab – 1st Dynasty (From Pahor AL. Ear nose and throat in Ancient Egypt. J Laryngol Otol. 1992;106:773–9. Courtesy of the Journal of Laryngology)

Fig. 66.2

Kind Dyer slab – 1st Dynasty (From Pahor AL. Ear nose and throat in Ancient Egypt. J Laryngol Otol. 1992;106:773–9. Courtesy of the Journal of Laryngology)

The procedure was also performed in the ancient Hindu culture and described in the Rig Veda, the sacred Hindu book of medicine written between 2000 and 1000 B.C. Alexander III of Macedon more commonly known as Alexander the Great (356–323 B.C.) reportedly performed a tracheotomy on one of his soldiers and “opened the trachea of a choking soldier with the point of his sword.” The prominent Roman surgeon Galen of Pergamon (130–200 B.C.) wrote that his colleague Asclepiasds of Bithynia performed the first elective tracheotomy. Early evidence of the procedure surfaced again in the medical text Epitome written by Paul of Aeginas (625–690 B.C.) with this description of tracheotomy: “In cases of inflammation of the mouth or palate, it is reasonable to use tracheotomy (pharyngotomy) in order to prevent suffocation. We cut the trachea below the upper part at the level of the third or fourth ring. For a better exposure of the trachea, the head needs to be reclined. A transverse incision is made in between two tracheal rings, so it is not the cartilage that is incised, but the tissue in between.” The procedure was deemed a success by “a wheezing noise escaping from the hole in the trachea and the loss of the patient’s voice.” For unknown reasons, the procedure fell out of favor during the fifth century, and its use was rarely documented over the next millennium. tracheotomy reemerged in the medical literature in 1546 when the Italian surgeon Antonia Musa Brasavola is credited with reintroducing the procedure on a patient dying from asphyxiation from an upper airway obstruction and is quoted as saying, “when there is no other possibility, in angina, of admitting air to the heart, we must incise the larynx below the abscess.” Hieronymus Fabricus (1537–1619) is credited with first using a cannula which was short and straight so as to reduce the risk of posterior tracheal wall puncture and flanges to prevent aspiration of the instrument.

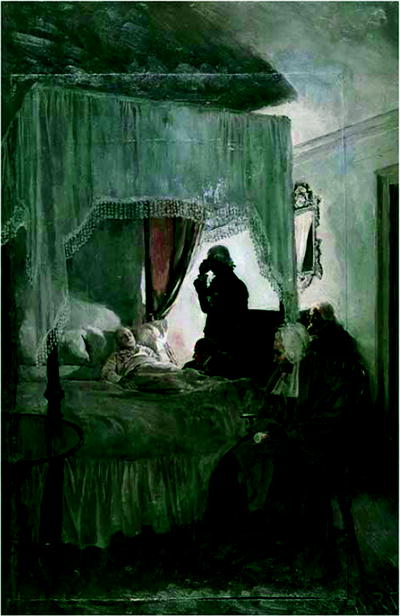

In 1626, another Italian surgeon, Sanctorio Sanctorius, performed the first percutaneous approach to tracheotomy and described the procedure by using a “ripping needle” to introduce a silver cannula into the tracheal lumen and then removed the needle. Despite the technical improvements in regard to the procedural approach to tracheotomy, it remained a highly morbid procedure leading to the majority of practicing surgeons to shy away from performing it. This most famously occurred on the evening of December 14, 1799, when a patient was fatally struck with “cynanche trachealis” presumed to be bacterial epiglottitis. He was surrounded at the bedside by 3 prominent physicians, Dr. James Craik, Dr. Gustav Brown, and Dr. Elisha Dick. At the time, bloodletting was a mainstay treatment and tracheotomy was still considered experimental. Dr. Dick had recently been trained in tracheotomy and reportedly a debate ensued between Dr. Dick and Dr. Craik in regard to the appropriate treatment. As the senior physician on the team, Dr. Craik vetoed this suggestion by Dr. Dick and continued to pursue bloodletting which was ineffective. Although tracheotomy would have likely saved his life, it was not performed, and at 10:20 pm that evening, George Washington, the first president of the United States of America, died with his wife Martha at his bedside (Fig. 66.3).

Fig. 66.3

The Death of Washington, Sketch from 1896 in Oil by Howard Pyle. Dr. James Craik is pictured standing, Dr. Gustavus Brown is seated, and Martha Washington sits at the foot of the bed (Courtesy of the Boston Public Library Print Department)

During the diphtheria epidemic of 1833, Pierre Bretonneau and his student Armand Trousseau were the first physicians to document using tracheotomy on a routine basis. During this epidemic, Dr. Trousseau was quoted as stating, “Today gentleman, I have performed this operation more than 200 times and I am reasonable happy to have a success in more than 25% of cases.” Trousseau was also the first to use a spreader to keep the trachea open during the procedure. In 1869, Trendelenburg developed the first cuffed tracheotomy tube, and although this was an improvement, due to its high operative mortality, tracheotomy continued to be used in limited circumstances at only a few institutions worldwide. The tracheotomy procedure further declined during the late 1800s. During that time, Dr. Joseph O’Dwyer joined the hospital staff at the Foundling Asylum of the Sisters of Charity in New York after completing his training at the College of Physicians and Surgeons in New York City. At that time, there continued to be a very high mortality of patients with laryngotracheal croup. From the period of 1869–1880, every patient who underwent a tracheotomy at the Foundling Asylum had died. Dr. O’Dwyer decided to make it his life’s work to discover a treatment to prevent suffocation without surgical intervention and, as a result, pioneered the orotracheal tube. In 1894, he presented his data at the National Sciences Research Workers Meeting in Nuremberg that 40% of the 1,324 cases he had treated had fully recovered.

It was not until the early twentieth century that tracheotomy regained popularity due to the standardization of open surgical tracheotomy by the famous American surgeon Chevalier Jackson. Jackson is credited with reducing the operative mortality associated with tracheotomy at that time from 25% to 1%. He recognized and emphasized the importance of adequate oxygenation during the procedure as well as airway control. He also further advanced all surgical techniques by recognizing the importance of postoperative care. In the 1930s, tracheotomy was advocated as an effective way to provide bronchopulmonary toilet in patients with polio. Due to the continued modern track record of safety associated with the placement of tracheotomy tubes along with the widespread use of positive pressure ventilation in the 1950s, there was considerable effort focused on the development of tracheotomy tubes as a means of providing long-term ventilatory support.

In 1955, Shelden introduced the first modern-day percutaneous tracheotomy set which closely resembled the approach fist described by Sanctorius 500 years earlier. The procedure used a trocar over a needle that resulted in multiple deaths secondary to airway and vascular injury and was abandoned. In 1967, Toye and Weinstein first used the Seldinger technique to safely introduce a cannula into the tracheal lumen. The technique was further refined by Pasquale Ciaglia in 1985 in what has now become one of the most popular techniques for percutaneous dilatational tracheotomy (PDT).

Tracheal Anatomy

As with all invasive procedures, knowledge of the anatomy is an essential prerequisite prior to proceeding with any surgical procedure. Basic airway anatomy as well as a thorough understanding of the surrounding vasculature and vital structures which approximate the trachea is required. The trachea is a centrally located unpaired organ which extends in an oblique fashion from the superficial position in the neck and deeper into the mediastinum. The average length of the adult trachea is 11 cm (range 10–13 cm). Along the course of the trachea, there are 18–22 incomplete or semicartilaginous rings with an anteroposterior diameter of 1.8 and 2.3 cm in the lateral dimension. The cricoid cartilage in the larynx has the only complete cartilaginous ring and has a membranous attachment to the first tracheal ring. The posterior wall of the trachea or membranous trachea is comprised of a flexible sheet of fibroelastic tissue between the ends of the tracheal rings and abut the anterior portion of the esophagus. The combination of the rigidity of the anterior two-thirds of the trachea with the flexibility of the poster one-third allow for a great range of flexibility and stability to withstand the forces of forced expiration and coughing and allow continued airway patency.

There are several structures which lie anterior to the trachea which should be identified prior to tracheotomy. The thyroid isthmus is located between second and third tracheal rings, the innominate artery most often crosses the anterior trachea in an oblique fashion distal or inferior to the third tracheal ring and the aortic arch crosses above the carina. The recurrent laryngeal nerves lie in close proximity to the trachea within the tracheoesophageal groove. The blood supply to the cervical trachea enters posterolaterally from the inferior thyroid artery. As a result, when performing a tracheotomy, dissection along the anterolateral plane is safest to avoid vascular injury (Fig. 66.4).

Fig. 66.4

Anatomic landmarks (Courtesy of Cook Critical Care, Bloomington, IN)

Indication and Timing

Although there has been a significant reduction in tracheal injury secondary to endotracheal intubation, there are pros and cons related to each technique (Table 66.1).

Table 66.1

Pros and cons of endotracheal tubes and tracheotomy tubes

PROS | CONS | |

|---|---|---|

Tracheotomy tube | Decreased work of breathing | Potential loss of airway |

Decreased auto-PEEP | Tracheal stenosis at stoma | |

Increased patient comfort | Tracheal stenosis/malacia at cuff | |

Decreased sedation | ||

Facilitates transfer out of ICU | Surgical training needed | |

Facilitates speech and swallowing | Surgical scar | |

Facilitates airway suctioning | ||

Increases patient mobility | ||

Endotracheal tube | Quickly reinserted under vision | Laryngeal injury |

Tracheal stenosis/malacia at cuff | ||

Deeper sedation | ||

Requires ICU level of care |

In the 1960s, Drs. Hermes Grillo and Joel Cooper first reported tracheal injury due to cuffed endotracheal tubes. Since that time, high-volume, low-pressure, cuffs for endotracheal tubes have since been developed which resulted in a reduction in tracheal injury. Despite this reduction, there remains a significant degree of other complications including vocal cord injury, subglottic stenosis, and tracheomalacia (Fig. 66.5).

Fig. 66.5

(a) and (b) Tracheal injury where the cuff has caused some tracheal injury (8b) which is best seen with the tube removed (8c) from the autopsy specimen (Courtesy of Joel Cooper, M.D.)

In addition, as more patients are ventilated for increasingly longer periods of time, there has been an associated increase in ventilator-associated pneumonia and mortality. Although tracheotomy can reduce some of these complications, the procedure itself has its own inherent complications, and as such, some studies recommend early tracheotomy as means of further reducing the additive effects of multiple procedures and the longer-term risks of prolong endotracheal intubation. The most recent 2001 American College of Chest Physicians guidelines for weaning and discontinuing ventilatory supports encourage early tracheotomy after patient stabilization if the patient needs prolonged mechanical ventilation more than 3 weeks after intubation where rates of ICU mortality and failure to wean increase. In the randomized controlled trial by Rumbak et al. comparing early (less than 48 h) versus late (14–16 days) tracheotomy in patients with respiratory failure, the early group had a significant decrease in mortality, pneumonia, and ventilator days. Terrangi et al. randomized 419 patients to receive early (6–8 days) vs. late (after 13–15 days) tracheotomy with a primary endpoint of incidence of ventilator-associated pneumonia and secondary endpoints of ventilator-free days, ICU-free days, and 28-day survival. There was a trend toward a decrease in VAP and a significant decrease in ICU days and successful weaning but no survival benefit. In a systematic review and meta-analysis by Dunham et al. comparing early versus late tracheotomy in trauma patients, there was benefit seen in the early tracheotomy group in ventilator days, ICU length of stay, and VAP only in the brain injury cohort.

To date, there are not enough well-designed studies to allow for a clear consensus or guidelines in regard to the timing of tracheotomy. Kollef et al. published a post hoc analysis of a prospective cohort study which found that patients who receive a tracheotomy have a lower mortality than those who do not, despite an increase in total days on mechanical ventilation and hospital length of stay. Although questions such as survival benefit and ventilator days remains in question, one must take into account other factors which have been established. Improved patient comfort, decreased need for sedatives, and increased ability to communicate with enhanced nursing care have all been shown to be improved by tracheotomy placement. Selection of patients who should undergo tracheotomy placement is a complex medical decision and as such needs to be individualized for each patient. Table 66.2 reviews suggested indications for PDT.

Table 66.2

Suggested indications for PDT

Prolonged mechanical ventilation estimated or anticipated to be longer than 7 days |

Enhancement of patient comfort prolonged weaning efforts |

Failed extubation |

Relief of upper airway obstruction |

Secretion management |

Need for bedside procedure secondary to increased risk of patient transfer to operating room |

Contraindications

As with all procedures, the first major contraindication is the performance of the procedure by an inexperienced provider without appropriate supervision and guidance. The large majority of PDT cases are elective, thus affording the proceduralist the luxury of performing a detailed history and physical examination to assess candidacy for bedside PDT (Table 66.3). Patients should be hemodynamically stable, and coagulopathy parameters should be corrected prior to proceeding with the procedure.

Table 66.3

Contraindications to PDT

Absolute |

• Absence of informed consent |

• Active site infection |

• Uncorrectable bleeding diathesis |

• Operator inexperience |

• Infants |

Relative |

• Uncorrectable coagulopathy/thrombocytopenia |

• Difficult airway |

• Morbid obesity |

• High ventilatory/positive end-expiratory pressure requirements |

• Pediatric population |

• Recent sternotomy |

• History of neck surgery |

• Emergent procedure |

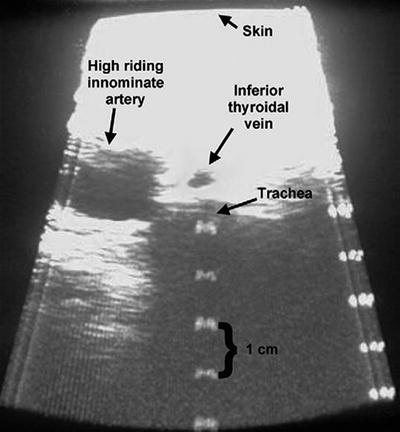

The neck anatomy should be carefully examined for high lying or crossing vasculature which greatly increases the risk of fistula formation. If these anatomic variants are identified, patients should be referred for open surgical tracheotomy to allow dissection and isolation of the surrounding vasculature. Ultrasound as a prescreening measure prior to PDT has been increasingly used in intensive care units. The use of an ultrasound probe with Doppler technology allows both a gross anatomic ultrasound examination, localization of the cartilaginous rings, and a vascular assessment that appears to reduce complications when used by a trained professional on a routine basis (Fig. 66.6). Although the overall risks during PDT are small, preoperative ultrasound assessment may further reduce these rare complications. In a study by Muhammad et al. where 497 PDT procedures were performed, six cases were aborted due to bleeding, and 18 cases had clinically significant bleeding during the procedure (incidence of 4.8%). In a postprocedure review of these patients, 4 had ultrasound findings which could have identified the risk preoperatively (2 inferior thyroidal veins, 1 high brachiocephalic, and 1 aberrant anterior jugular communicating vein).