Percutaneous Approaches to Valvular Disease

Alec Vahanian

Eric Brochet

David Messika-Zeitoun

Bernard Iung

Until the early 1980s surgery was the only possible treatment for severe valvular lesions, then a new alternative appeared: percutaneous valve intervention. We deal here with percutaneous valvuloplasty for acquired valvular stenoses, and we briefly describe the very first experiences of percutaneous valve replacement and repair.

PERCUTANEOUS MITRAL COMMISSUROTOMY

The first person to perform percutaneous mitral commissurotomy (PMC) was K. Inoue, in the early 1980s (1).

Technique

PMC probably should be carried out only by groups with experience of transseptal catheterization, because this is the first step of the procedure. To assure their technical performance and ability to select patients, operators should have successfully carried out an adequate number of procedures on a regular basis. The transarterial approach could represent an alternative to transseptal catheterization in rare cases where the transseptal approach is contraindicated or impossible (2).

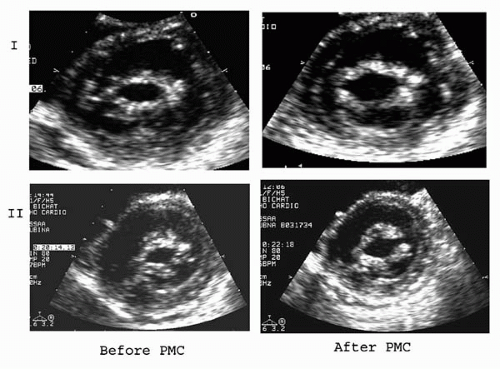

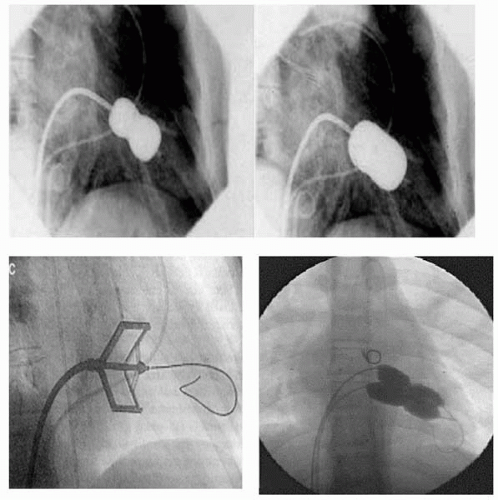

The Inoue technique, now the most popular worldwide (3,4), uses the Inoue balloon, which enables fast positioning across the valve and is pressure-extensible to allow stepwise dilatations to be performed. Comparisons suggest that this technique makes the procedure easier, has overall equivalent efficacy to, and carries a lower risk than other techniques. In developing countries, economic constraints lead to a residual use of the double-balloon technique (5) and the reusable metallic commissurotome (6) (Fig. 25.1). Echocardiographic monitoring enables the early detection of complications and provides essential information on the mitral opening (Fig. 25.2). The following criteria have been proposed for the desired endpoint of the procedure: valve area 1cm2/m2 BSA; complete opening of at least one commissurotome; appearance or increment of regurgitation greater than grade 1/4. However, these criteria should be adapted to individual circumstances.

Immediate Results

PMC usually allows for a doubling in valve area, with a final valve area of around 2 cm2, resulting in an immediate decrease in pulmonary pressures, both at rest and during exercise.

Risks

The failure rates range from 1% to 15%, and these mostly reflect the learning curve of the operators (2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7). Procedural mortality ranges from 0% to 3%. The incidence of hemopericardium varies from 0.5% to 5%. Embolism is encountered in 0.5% to 5% of cases. Severe mitral regurgitation (MR) occurs in 2% to 10% of patients, mostly when a heterogeneous distribution of the morphologic abnormalities is present (8). Urgent surgery is seldom required for complications (<1% in experienced centers) such as massive hemopericardium or severe MR with poor hemodynamic tolerance.

Figure 25.1. Inoue balloon technique (upper panel). Metallic commissurotome in the open position (lower panel left). Double-balloon technique (multitrack) (lower panel right). |

Long-Term Results

When immediate results are unsatisfactory, surgery is usually required in the following months. Conversely, after successful PMC, long-term results are good in the majority of cases, 35% to 56% of patients being free of symptoms without reintervention after 10 years (9,10). When functional deterioration occurs, it is late and mainly related to restenosis (around 40% after 7 years) (9,11). Repeat PMC can be proposed in selected patients with favorable characteristics, if restenosis leads to symptoms, occurs several years after an initially successful procedure, and the predominant mechanism of restenosis is commissural refusion (12). Finally, repeat PMC is the sole option in patients with contraindications for surgery. Successful PMC also has been shown to reduce embolic risk (13).

Selection of Candidates

The first step is to eliminate contraindications (Table 25.1). To rule out the possibility of left atrial thrombosis, transesophageal echocardiography must be performed before the procedure. No consensus has been reached in cases with thrombosis localized in the left atrial appendage.

Echocardiographic assessment allows the classification of patients into anatomic groups, with a view to predicting results. Most authors use the Wilkins’ score (14) (Table 25.2), whereas others use a more general assessment of valve anatomy (4). More recently, scores have been developed that take into account the uneven distribution of anatomic abnormalities, in particular in commissural areas (15). Because predicting the results of PMC is multifactorial, other factors such as age, history of commissurotomy, functional class, small mitral valve area, and presence of tricuspid regurgitation, which are all independent predictors of results (9,10), should also be taken into account.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree