Pelvic Congestion Syndrome

Derek P. Nathan

Mark H. Meissner

Pelvic congestion syndrome was first described by Taylor in 1949.1 He, as well as others, demonstrated that pelvic varicosities and venous congestion were consistently found in women with what was then known as the pelvic pain syndrome.2 Reflux and obstruction affecting the pelvic veins may present in a variety of ways including chronic pelvic pain; varicose veins affecting the legs, vulva, perineum, or gluteal cleft; or with symptoms of flank pain and hematuria associated with the nutcracker syndrome.

Chronic pelvic pain is defined as pain below the umbilicus that lasts for 6 months or longer. It affects 15% of women 18 to 50 years of age in the United States and may be associated with significant disability and distress.3 Fifteen percent of women with chronic pelvic pain report time lost from employment, and 45% report decreased work productivity. Despite the significant clinical and socioeconomic impact, a definitive diagnosis is made in fewer than 40% of women with chronic pelvic pain. Although a variety of disorders, including endometriosis, uterine leiomyoma, and pelvic inflammatory disease, may be associated with chronic pelvic pain, pelvic congestion syndrome is the second leading cause of chronic pelvic pain and accounts for as many as 31% of cases.4 The modern diagnosis of pelvic congestion syndrome is based upon correlation of the patient’s clinical presentation with diagnostic imaging findings demonstrating reflux and/or obstruction in the pelvic venous system.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Pelvic venous disorders primarily affect premenopausal, multiparous women and may be associated with a variety of clinical presentations. Among 42 women with pelvic varices, the mean onset of symptoms was after the second pregnancy at a mean age of 31.9 years. Symptoms were related to vulvar varices in 74%, lower extremity varices in 43%, and chronic pelvic pain in 26%.5

Beard et al6 compared the clinical features of women with chronic pelvic pain due to pelvic congestion to those of women with pain due to other pelvic pathologies. Women with symptomatic pelvic congestion were younger and more often multiparous. Pain associated with pelvic congestion is often described as dull and aching with occasional sharp exacerbations. It is improved in the supine position but worsened in positions that increase pelvic blood flow, such as standing or sitting, as well as during menstruation.4,7 Such patients may also report dyspareunia, dysmenorrhea, and dysuria, and they have higher rates of anxiety and depression than do women with chronic pelvic pain from other causes.4 Symptoms usually improve or resolve with menopause.6

Pelvic venous disorders may also be associated with varicose veins, with or without pelvic pain. Atypically distributed varices, specifically those localized below the gluteal crease, on or below the perineum in the medial thigh, or on the vulva, should raise the suspicion of pelvic venous reflux. However, more typically distributed varices may also arise from communications between the deep and superficial external pudendal tributaries of the great saphenous vein and the internal iliac veins. Importantly, depending on demographics, one-quarter to one-third of recurrent varicose veins in women arise from a pelvic source.8

Aortomesenteric compression of the left renal vein (the nutcracker syndrome) may be associated with left flank pain and hematuria as well as pelvic congestion symptoms in women and a left-sided varicocele in men.9 The nutcracker syndrome has a bimodal age distribution, with one peak in adolescents and young adults and a second peak in women in their third to fourth decades.

ANATOMY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The diagnosis and management of pelvic venous disorders requires a thorough understanding of the complicated venous anatomy. The venous drainage of the pelvis occurs through the ovarian veins, tributaries of the internal iliac veins, and the femoral veins. These three systems have multiple interconnections, including frequent drainage across the pelvis.10 The ovarian veins drain the venous territories of the parametrium, cervix, mesosalpinx, and pampiniform plexus, which may also drain through the internal iliac veins as a collateral pathway. These plexuses form the ovarian vein, which may have two to three trunks before classically forming a single vein at the level of the fourth lumbar vertebra. Although variations occur, the right ovarian vein usually drains directly into the inferior vena cava, while the left ovarian vein drains into the left renal vein. Together with the left adrenal, ascending lumbar, hemiazygous, peri-ureteric, and capsular veins, the left ovarian vein may be the primary drainage of the left kidney in cases of aortomesenteric compression of the left renal vein. The normal ovarian vein has a diameter of approximately 3 mm, although this increases with pregnancy, and it usually has two or three valves.

The internal iliac vein is formed by the union of the obturator, branches of the internal pudendal, and gluteal veins, which originate in the thigh, perineum, and buttock, respectively. The internal iliac vein may have multiple collaterals, both across the pelvis and through the internal pudendal and obturator tributaries to the ovarian and femoral veins. Four pelvic escape points have been described as connections between internal iliac tributaries and the lower extremity veins: the inguinal (I) point arising from the round ligament vein, the perineal (P) point arising from the pudendal veins, the obturator (O) point carrying reflux from the obturator vein, and the gluteal (G) points arising from the superior and inferior gluteal veins.11

As with other venous disorders, pelvic venous syndromes may result from either reflux or obstruction. Both the ovarian veins and the internal iliac tributaries contain valves that can become incompetent, leading to pelvic venous reflux. Ovarian vein reflux may be demonstrated in up to 47% of women. Pregnancy is associated with as much as a 60-fold increase in pelvic blood flow as well as hormonally mediated ovarian and uterine vein dilation.7,12,13 Ovarian vein dilation ultimately leads to valvular incompetence and retrograde flow or reflux. The high capacitance of the pelvic venous system is facilitated by the pelvic veins’ lack of a supporting sheath of fascia as in the veins of the lower and upper extremities. The central role of hormonally mediated changes in the pelvic venous circulation in pelvic congestion syndrome is demonstrated by the significant improvement in symptoms with pharmacologic ovarian suppression.4 The role of pelvic vein dilatation is similarly demonstrated by the observation that dihydroergotamine, a vasoconstrictive agent that increases venous tone and reduces venous capacitance, is effective in reducing venographic venous diameters, increasing contrast clearance, and decreasing venous congestion in women with chronic pelvic pain.14

Pelvic congestion syndrome may also result from venous obstruction, usually related to compression of the common iliac veins, resulting in internal iliac venous reflux, or compression of the left renal vein, resulting in left ovarian venous reflux. May-Thurner syndrome, which most commonly arises from compression of the left common iliac vein by the right common iliac artery, and the nutcracker syndrome, which most commonly represents compression of the left renal vein by the superior mesenteric artery, are the most common compression syndromes in the abdomen. Less commonly, a retroaortic left renal vein may be compressed between the aorta and vertebral column (posterior nutcracker syndrome). Although most commonly associated with deep venous thrombosis, iliac vein compression may occasionally lead to varices associated with internal iliac venous reflux.13 As discussed above, the left ovarian vein may also function as a refluxing collateral pathway draining the kidney in cases of symptomatic aortomesenteric compression of the left renal vein.

DIAGNOSTIC CONSIDERATIONS

The diagnosis of pelvic congestion syndrome can be difficult, and it is common for women to consult multiple physicians prior to obtaining a definitive diagnosis. The differential diagnosis is quite broad, including endometriosis, pelvic adhesions, atypical menstrual pain, pelvic inflammatory disease, leiomyoma, urologic disorders, pelvic congestion syndrome, and irritable bowel syndrome. Furthermore, a high prevalence of psychiatric disorders among women with pelvic congestion syndrome, such as depression and anxiety, may obfuscate the diagnosis.4 As described above, the anatomy and pathophysiology are quite complex, with both reflux and obstruction in multiple interconnected venous beds. Finally, the availability and quality of the imaging studies used to establish the diagnosis may vary widely between institutions.

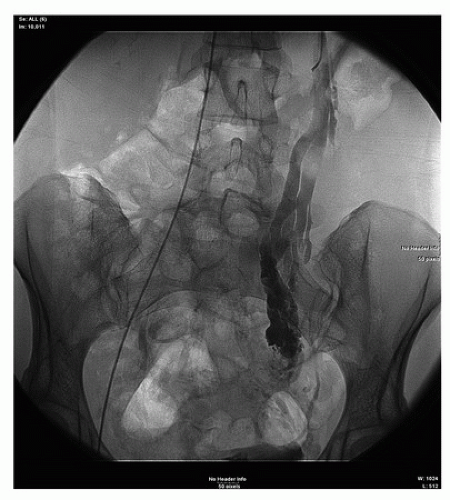

Selective left renal, bilateral ovarian, and bilateral internal iliac venography is often considered the gold standard for the diagnosis of pelvic congestion syndrome (Fig. 25.1). Either a common femoral vein or right internal jugular vein approach may be utilized for catheter access, although due to the acute angulation of its confluence with the inferior vena cava, selective catheterization of the right ovarian vein may be difficult from the groin. Based on transuterine pelvic venography, Beard et al2 described the venographic criteria for pelvic congestion as (1) an ovarian vein diameter ≥6 mm, (2) contrast retention within the pelvic veins of greater than 20 seconds, and (3) congestion of the pelvic venous plexus and/or opacification of the ipsilateral (or contralateral) internal iliac vein. Each variable is assigned a value of 1 to 3 depending on the degree of abnormality with a score greater than 5 being diagnostic of pelvic congestion syndrome. Venographic filling of vulvovaginal and thigh varicosities is also diagnostic of a pelvic source of reflux (Fig. 25.2).

The invasive nature of venography has led to the investigation of noninvasive imaging modalities for diagnosis of pelvic congestion syndrome. Both computed tomographic (CT) and magnetic resonance (MR) venography can be used to document compression of the left renal and iliac veins, to measure ovarian vein diameters, and to identify pelvic varices. CT- and MR-based criteria for pelvic congestion syndrome include an ovarian vein diameter greater than 8 mm and more than four tortuous parauterine veins measuring greater than 4 mm in diameter (Fig. 25.3).15 Unfortunately, standard cross-sectional imaging gives no physiologic information regarding the hemodynamic significance of reflux or

obstruction, and the quality of studies varies widely between institutions.

obstruction, and the quality of studies varies widely between institutions.

FIGURE 25.1. Selective contrast venography demonstrating a dilated, refluxing left ovarian vein communicating with extensive pelvic varicosities. |

FIGURE 25.2. Balloon occlusion contrast venography demonstrating communication between internal iliac venous tributaries and the great saphenous vein. |

Ultrasound provides a noninvasive means for identifying women who might benefit from diagnostic and therapeutic pelvic venography. Moreover, ultrasound can identify other conditions, such as leiomyoma or endometriosis, which are important in the diagnostic workup of the patient. Both transabdominal and transvaginal ultrasound have been widely used, sometimes in combination, for the evaluation of pelvic congestion syndrome.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree