Pediatric and Congenital Tumors

Pediatric and Congenital Tumors

Joseph J. Maleszewski, M.D.

Allen P. Burke, M.D.

General

Incidence

Pediatric heart tumors are rare and are the primary indication in <1% of heart surgeries in a children.

1

Clinical

There is no obvious sex predilection for most of the cardiac tumors that arise in children. In surgically resected tumors, the mean age is ˜4 years, with a range of 1 day to 18 years, or the definition of the upper limit of a pediatric age group.

2 Intrauterine detection of heart tumors has become common, especially for intrapericardial teratoma.

3

Histopathologic Types

In general, there are five entities that are considered pediatric and/or congenital tumors of the heart. These include rhabdomyoma, fibroma, histiocytoid cardiomyopathy, and inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (IMT). Cardiac hamartomas (discussed in Chapter 183) and cystic

tumor of the atrioventricular node are likely also present at birth and could be classified as pediatric/congenital tumors, but often do not present until adulthood.

The most common pediatric heart tumor in children < age 5 is rhabdomyoma, followed by cardiac fibroma (

Tables 180.1 and

180.2). In neonates and fetuses, intrapericardial teratomas tend to be more common (see

Chapter 186). In older children, myxomas are more common.

Myxomas are discussed in Chapter 181. In children, myxomas are rare under age 10 and are usually recognized during investigation of a murmur. As in adults, most are located in the left atrium. In children and young adults, there is a higher incidence of Carney complex than in adults with cardiac myxoma.

1

Imaging

Echocardiography, ultrasound, and magnetic resonance imaging are used most commonly to image cardiac masses in children and fetuses. Echocardiography is noninvasive and radiation free, but has poor soft tissue characterization in larger children and suboptimal evaluation of extracardiac structures. Ultrasound is the modality of choice for evaluating fetal abnormalities and has excellent sensitivity for such.

Magnetic resonance imaging is the modality of choice for cardiac masses, especially in children. There is no use of ionizing radiation. With the use of intravenous contrast, it is excellent in differentiating neoplasms from thrombus as well as discriminating between benign and malignant cardiac masses. The extent of myocardial, pericardial, valvular, and coronary arterial involvement can also be gauged well by this modality.

Computed tomography can provide additional anatomic information and tissue characterization such as calcification and offers assessment of patients with suspected metastatic disease, especially in conjunction with positron emission tomography.

4

Treatment and Prognosis

The treatment of most heart tumors is surgical resection, with the exception of rhabdomyoma, which may spontaneously regress. The prognosis for excised benign tumors is excellent, with a 93% 5-year survival.

2 The highest intraoperative mortality is seen with cardiac fibroma, because of the frequent large size.

1 The prognosis for malignant tumors is poor, with a 40% 5-year survival.

2

Rhabdomyoma

Clinical Findings

Children with rhabdomyomas typically present, before the age of 10 years, with murmurs, arrhythmias, or heart failure. There are extracardiac manifestations of tuberous sclerosis in >50% of patients.

1,2,5Only 23% of children with cardiac rhabdomyoma require heart surgery, because the tumors have a propensity to spontaneously regress. Those that require surgery generally have luminal obstructive lesions that usually require intervention prior to age 3 months.

6

Gross Pathology

Cardiac rhabdomyomas usually involve the ventricles, with atrial involvement in fewer than 10% of cases. Most (>60%) occur in multiples, particularly those associated with tuberous sclerosis.

On gross examination, cardiac rhabdomyomas are lobulated, tanwhite or yellow nodules with a distinct demarcation from the surrounding myocardium. They range from a few millimeters up to 10 cm. Rarely, they may occur as a miliary studding of the myocardium.

7

Microscopic Pathology

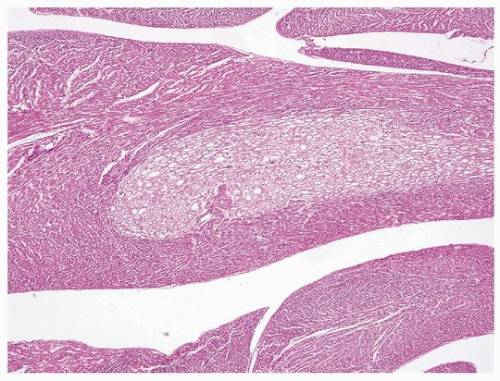

Cardiac rhabdomyomas form well-demarcated unencapsulated lobules of vacuolated tumor cells identified easily on low magnification (

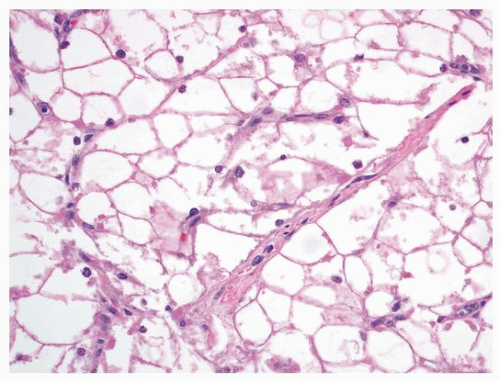

Fig. 180.1). The lobules consist of round polygonal cells with cytoplasmic clearing and small nuclei (

Fig. 180.2). Strands of eosinophilic cytoplasm often emanate from the center of the rhabdomyoma cell and extent radially to the sarcoplasmic membrane, giving the appearance of a spider (so-called

spider cells).

Calcification is usually absent, in contrast to a large proportion of fibromas. On immunohistochemical studies, the tumor cells reflect

their myogenous origin and show positivity for vimentin, actin, desmin, and myoglobin. Hamartin and tuberin, the protein products of the genes associated with TSC, namely,

TSC1 and

TSC2, respectively, are also positive in rhabdomyomas, with some evidence pointing to a down-regulation status of these proteins in rhabdomyoma cells when compared to normal myocytes.

8

Treatment and Prognosis

The prognosis for cardiac rhabdomyoma is excellent, as the tumor is benign and generally undergoes spontaneous regression. In those children who require surgery for obstructive lesions, there is an operative mortality of around 7%.

1 More recently, drugs that inhibit the mTOR pathway have proven effective in hastening regression and may greatly reduce the number of surgical resections for this tumor.

9

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access