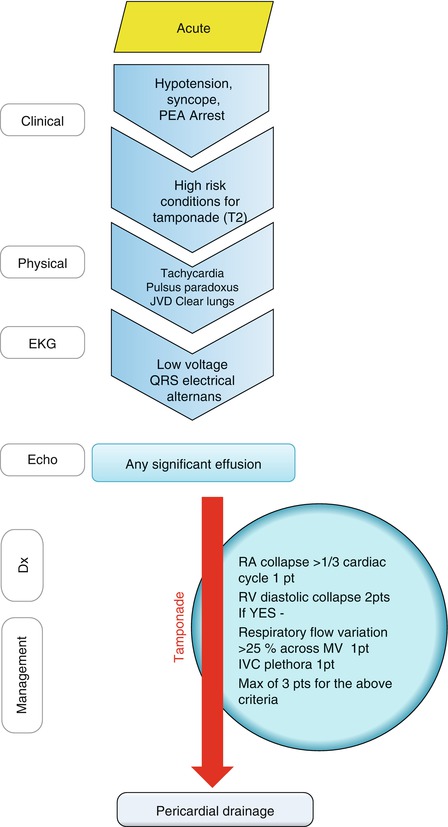

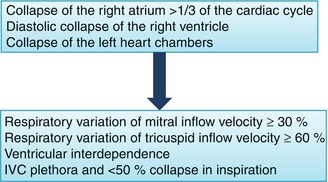

Fig. 13.1

Novel “CHASER” pathway for the management of pericardial disease. The figure outlines a unified, stepwise pathway-based approach to pericardial disease management

The Advanced Cardiac Admission Program

The “Advanced Cardiac Admission Program (ACAP)” was launched at St Luke’s Roosevelt Hospital Center in New York, in 2004. It consists of a series of projects which have been developed to bridge the gap between published guidelines and implementation during “real world” patient care (available at: www.nycardiologypathways.org). The pericardial disease management pathway is the ninth project of the ACAP program [2].

How to Use the Pathway

Entering the Pathway

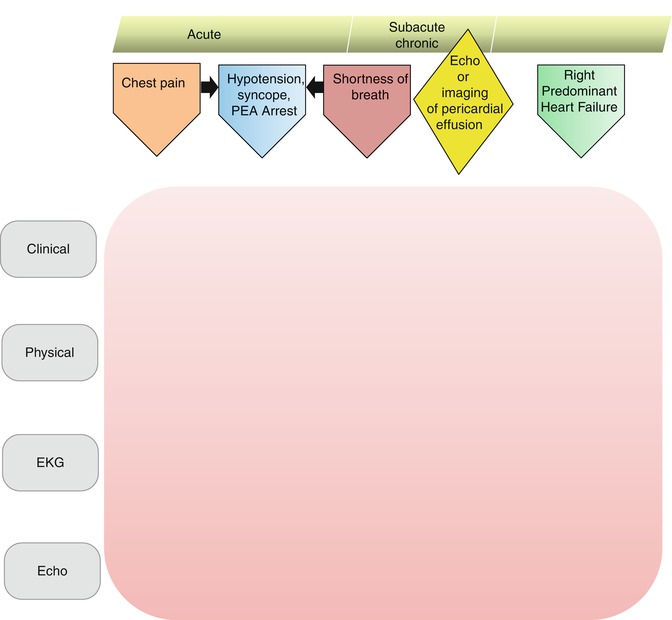

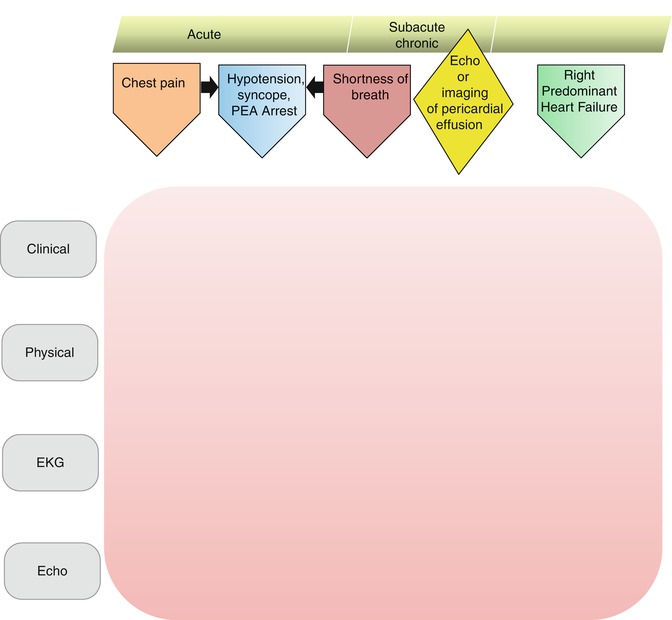

Despite the broad range of pericardial pathologies, there is a limited number of clinical presentations that would make a clinician suspect pericardial disease (Fig. 13.2). We assigned each clinical presentation a certain pathway which starts with patient’s complaints and continues along the lines of further work-up, diagnosis, and management. Typical clinical presentations in patients with pericardial disease include chest pain, hypotension/arrest, dyspnea, and right-predominant heart failure. Incidental finding of pericardial effusion during imaging study is also a common clinical scenario. Figure 13.2 outlines the entry points into the pericardial disease management pathway. The timeline of symptom development is a continuum ranging from acute, immediate presentation to subacute and chronic symptoms. A systematic approach to patients with suspected pericardial disease starts with the chief presenting complaint and is followed by a history taking, physical examination, electrocardiogram (EKG), and echocardiography. Further diagnostic testing is tailored to the initial findings.

Fig. 13.2

Entry points into the pericardial disease pathway. The entry points based on the initial clinical presentation form “CHASER” acronym

The following are the five entry points:

1.

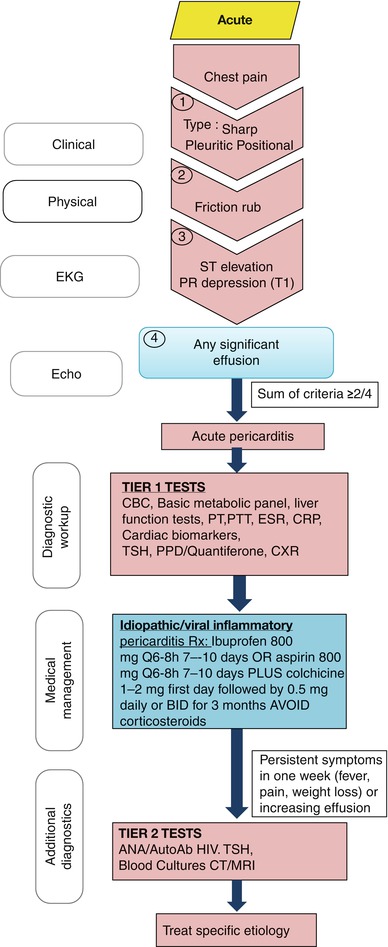

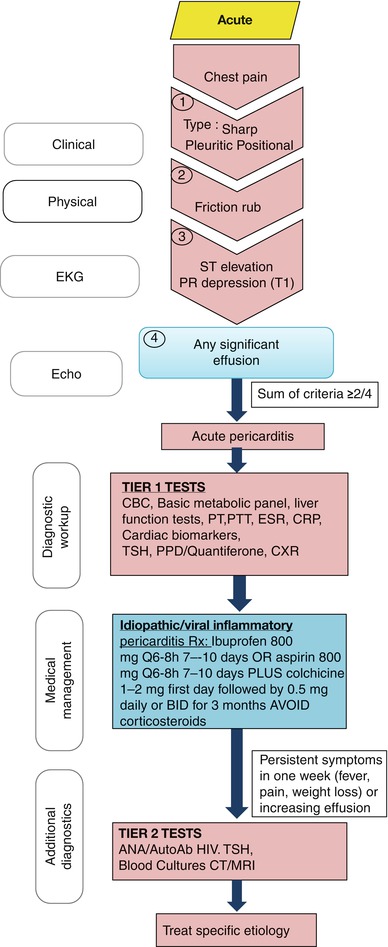

Chest Pain

Acute pericarditis should be considered in the differential diagnosis of any patient presenting with chest pain along with other etiologies. The chest pain algorithm of the pathway is outlined in Fig. 13.3. The diagnosis of acute pericarditis relies on the following four cardinal features: characteristic chest pain which is pleuritic and positional, friction rub on physical examination, characteristic evolving EKG changes (Table 13.1), and pericardial effusion demonstrated by echocardiography [3–5]. Presence of at least two of these features is usually diagnostic of acute pericarditis. Most cases of acute pericarditis in the western world are idiopathic or viral but other causes should also be considered [6]. Initial testing in all patients with acute pericarditis should include tier 1 testing (Fig. 13.3) [7]. Positive cardiac biomarkers indicate myocardial involvement. Inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein can be followed sequentially to monitor disease progression and response to treatment. Typical treatment includes nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents at full doses for 7–10 days [1]. We recommend the following doses: ibuprofen 600–800 mg every 6–8 h for 7–10 days or aspirin 800 mg every 6–8 h for 7–10 days. In postmyocardial infarction pericarditis, aspirin is preferred. In patients without contraindications, colchicines at a dose of 1–2 mg first day followed by 0.5 mg daily or twice daily for 3 months should be given as it reduces the rate of recurrence substantially [5, 8].

Fig. 13.3

Evaluation of chest pain in patient with possible acute pericarditis. A stepwise algorithm outlines evaluation and management of chest pain patients suspected to have acute pericarditis

Table 13.1

EKG features of acute pericarditis

Stage 1: diffuse ST segment elevation and PR segment depression |

Stage 2: normalization of ST segment changes |

Stage 3: diffuse T wave inversion |

Stage 4: normalization of T wave changes |

Corticosteroids increase the likelihood of relapse and should be avoided unless specifically indicated (e.g., in patients with connective tissue disease) [5, 9]. Patients with idiopathic or viral pericarditis usually respond promptly to treatment. Patients with persistent symptoms or with atypical clinical features are more likely to have other causes of pericarditis such as connective tissue disease and should undergo tier 2 testing as seen in Fig. 13.3 [10]. Those tests include imaging studies such as computed tomography scan of the chest or magnetic resonance imaging [1]. Corticosteroids can be used as a last resort for those patients if no specific cause was found [1].

2.

Hypotension, Syncope, or Pulseless Electrical Activity Arrest

Patients with tamponade can have an acute, dramatic presentation like patients with acute ascending aortic dissection involving the pericardial sac, or these patients can present with subacute symptoms of chest pain, dyspnea, and syncope like patients with neoplastic pericarditis. Cardiac tamponade should be suspected in any patients with hypotension, collapse, and pulseless electrical activity arrest (Fig. 13.4), and high-risk conditions commonly associated with tamponade should be specifically thought (Table 13.2) [11]. These include blunt chest trauma, recent procedure/intervention (e.g., electrophysiology procedures and coronary interventions), chest surgery, and aortic dissection. Neoplastic pericardial effusion, tuberculous pericarditis, and uncommonly idiopathic pericarditis can progress to tamponade. Physical examination findings should focus on pulsus paradoxus, jugular vein pressure, and lung auscultation. EKG findings may include low voltage QRS complex size and finding of electrical alternans. Echocardiography is essential in diagnosing pericardial effusion and confirming tamponade by the echocardiographic signs of hemodynamic compromise (Fig. 13.5). Echocardiography is also commonly used for guiding the intervention. Pericardiocentesis can be lifesaving in these patients.

Fig. 13.4

Approach to a patient with hypotension, syncope or pulseless electrical activity (PEA) arrest with possible pericardial tamponade. Initial clinical evaluation of patients suspected to have cardiac tamponade is outlined in the figure

Table 13.2

High-risk conditions for tamponade

Advanced renal failure |

Aortic dissection |

Chest trauma |

Connective tissue disease |

Malignancy |

Purulent infection |

Recent acute coronary syndrome |

Surgery/intervention |

Suspected tuberculosis |

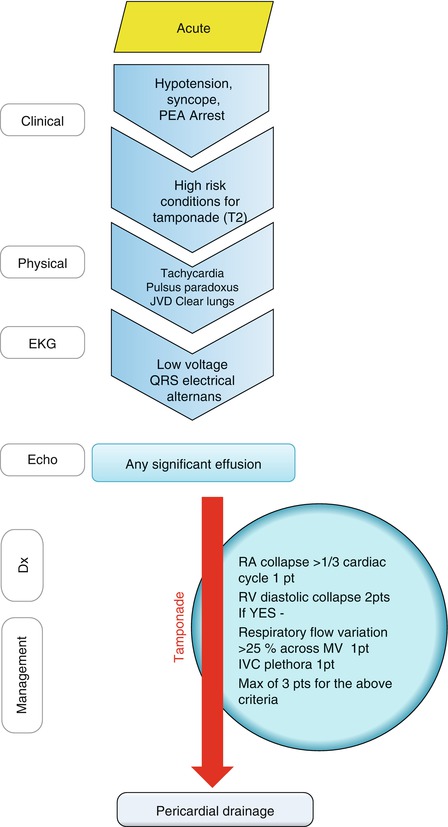

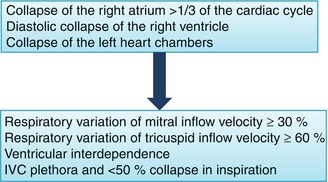

Fig. 13.5

Echocardiographic signs of hemodynamic compromise. The findings of heart chamber collapse are presented in order of decreasing sensitivity and increasing specificity. Confirmatory signs include respiratory variation across the atrioventricular valves, ventricular interdependence, and inferior vena cava (IVC) plethora

3.

Dyspnea

Patients with significant pericardial effusion often present with dyspnea, poor exercise tolerance, chest discomfort, and fatigue. Although the differential diagnosis of dyspnea is broad, it should include pericardial effusion (Fig. 13.6). The pericardium can be the primary focus for the disease as in most cases of acute pericarditis or it can be involved in a systemic process such as malignancy, endocrine diseases, or rheumatic diseases. In every patient with suspected pericardial disease, a systematic approach and consideration of possible etiologies are important parts of clinical reasoning (Table 13.3). These patients are hemodynamically stable and have no clinical signs of tamponade. EKG characteristics commonly include low voltage QRS complex size. Pulsus alternans is occasionally seen with large effusions without tamponade [11]. Echocardiography is an effective and inexpensive tool in diagnosing pericardial effusion.

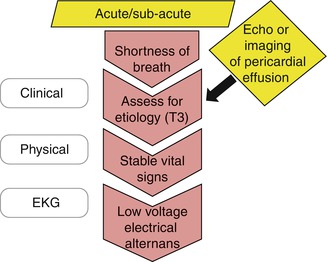

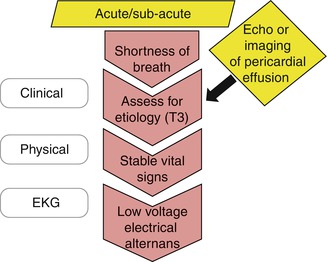

Fig. 13.6

Approach to a patient with dyspnea and possible pericardial effusion. Initial clinical evaluation of patients suspected to have pericardial effusion is outlined in the figure. Some patients are diagnosed with incidental pericardial effusion during imaging study done for other indications

Table 13.3

Causes of pericardial disease

Endocrine |

Hemopericardium (trauma, procedure, aortic dissection) |

Idiopathic |

Infectious (including viral, tuberculosis, and purulent) |

Medications |

Neoplastic |

Perimyocardial infarction |

Postcardiotomy syndrome |

Radiation |

Renal failure |

Rheumatic/autoimmune diseases |

4.

Incidental Finding of Pericardial Effusion

Sometimes, pericardial effusion is found as an incidental finding in patients worked-up for other causes. Although it is important to search systematically for possible etiologies of pericardial disease in each individual patient (Table 13.3), a substantial number of these cases remain unexplained [12, 13]. In patients with moderate to large effusion, tier 1 and tier 2 testing seem reasonable [12]. If a specific cause is found, it should be addressed. In patients with no obvious clue to the cause of the effusion and no evidence of hemodynamic compromise, elevated inflammatory markers suggest acute idiopathic pericarditis and trial of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents is justified. If inflammatory markers are within normal limits and there is no evidence of hemodynamic compromise, idiopathic pericardial effusion is high on the list of differential diagnosis [12]. Some patients with pericardial effusion have elevated right-sided pressures after pericardial drainage and they might have effusive-constrictive pericarditis [14].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree