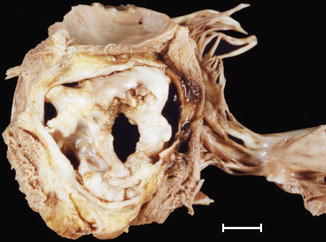

Fig. 7.1

Cross-sectional view at the level of the semilunar valves. In the aortic valve, the right coronary artery ostium can be observed in the right sinus and the beginning of the left coronary artery trunk next to the left sinus (arrows)

7.2.1 Aortic Stenosis

Aortic stenosis is the most common cardiac valvulopathy in Europe and North America. The most frequent aetiology of aortic stenosis is valve degeneration and calcification associated with aging, followed by congenital conditions, mainly bicuspid aortic valve, which is more common in younger patients. Rheumatic aetiology is rare. Depending on the location of the stenosis, aortic stenosis can be valvular (at the level of the leaflets), supravalvular (above the leaflets) and subvalvular (below the annulus) (Table 7.1).

Table 7.1

Morphological classification of aortic stenosis

Valvular | Supravalvular | Subvalvular |

|---|---|---|

Congenital | Membranous | Membranous |

Bicuspid | Hourglass deformity | Tunnel-like |

Unicuspid | Hypoplastic | Obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy |

Acquired | ||

Senile calcific | ||

Postinflammatory | ||

Mixed | ||

Aortic stenosis produces pressure overload in the left ventricle characterized by left ventricular hypertrophy without dilation, although in very advanced stages ventricular dilation and dysfunction may occur. Patients may be asymptomatic for many years despite having a morphologically-severe stenosis. When cardiovascular symptoms appear (syncope, angina, dyspnea or heart failure), valve replacement is usually required, in the majority of cases by surgical intervention. The technical development of percutaneous aortic valve replacement offers a new hope for patients at high risk for surgical intervention.

7.2.1.1 Aortic Valve Stenosis

Congenital Conditions

Bicuspid Aortic Valve

Bicuspid aortic valve (BAV) is one of the most common congenital heart diseases, with an incidence of 1–2 % in the general population and a strong male predominance (4:1). Several familial cases have been described in an autosomal dominant pattern with variable penetrance, and it is frequent in people affected by Turner’s syndrome. BAV occurs due to alterations in the process of valvulogenesis and leaflet formation. The two cusps are generally asymmetric and 75 % of these present a raphe or abortive commissure in the midline of the larger cusp. This raphe does not reach the aortic wall and contains elastic fibres, features that allow its differentiation from a post-inflammatory commissural fusion.

In up to 80 % of cases, fusion takes place between the right and the left coronary cusps in such a way that the leaflets are orientated in an anterior and posterior manner. The raphe is usually found in an anterior position with the coronary artery ostia located at both sides of the raphe (Subtype A) (Fig. 7.2). Coarctaction of the aorta is associated with this type of malformation.

Fig. 7.2

Schematic illustration of the different modalities of bicuspid aortic valve (Reproduced with permission from Fernández et al. 2010)

Less frequently, the commissure between the right-coronary and non-coronary cusps is absent and the leaflets are orientated to the right and to the left (Subtype B) (Fig. 7.3). The raphe usually locates in the right leaflet (Fig. 7.4). This morphology is associated with a greater severity of valve dysfunction (stenosis and aortic valve regurgitation).

Fig. 7.3

Bicuspid aortic valve. The origin of the coronary arteries can be appreciated in each of the sinuses. BAV was found during autopsy of a 41-year-old male who died from ischaemic heart disease

Fig. 7.4

Calcification of a bicuspid aortic valve. Sudden death in a 55-year-old male. Bicuspid valve with a calcified raphe located between the right and the posterior sinuses (Subtype B). Heart weight was 594 g and there was LV hypertrophy

The most common complication of BAV is aortic valve stenosis caused by the progressive and degenerative process of dystrophic calcification (Figs. 7.4, 7.5 and 7.6). Stenosis of the bicuspid aortic valve occurs approximately two decades earlier than in the tricuspid valve. In cases of severe calcification, the differentiation between a bicuspid aortic valve and a process of calcification on a valve with post-inflammatory fibrosis becomes a very difficult task.

Fig. 7.5

Bicuspid aortic valve with dysplastic and partially calcified leaflets. A 31-year-old male who died suddenly while playing football. The heart weighed 640 g and showed severe concentric LV hypertrophy

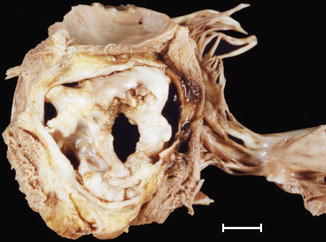

Fig. 7.6

Calcification of a bicuspid aortic valve. Sudden death in a 47-year-old male. A bicuspid aortic valve with heavily calcified leaflets, causing a significant obstruction of the LV outflow tract, which ultimately led to cardiac hypertrophy with a heart weight of 760 g

In up to 20 % of patients with congenital aortic stenosis, other concomitant cardiovascular abnormalities exist. For example, an association with aortic dissection is common (Fig. 7.7) and complications such as infective or rheumatic endocarditis may occur, causing mixed forms of aortic stenosis (Fig. 7.8).

Fig. 7.7

Aortic dissection associated with bicuspid aortic valve. A 30-year-old male. In the hours prior to death he presented prodromal symptoms such as chest pain. The cause of death was cardiac tamponade due to haemopericardium secondary to a type A aortic dissection. Dissection of the aortic wall, with intimal tear and dilatation of the aortic root can be appreciated in the image

Fig. 7.8

Mixed aortic stenosis. A 61-year-old male who suddenly fainted while walking in the street. A bicuspid aortic valve in addition to commissural fusion (arrow), probably secondary to an inflammatory process. Heart weight: 345 g, with LV wall thickness: 18 mm

Unicuspid Aortic Valve

There are two types of congenital unicuspid aortic valves: (1) the acommissural or dome-shape unicuspid valve, with three aborted commissures (or raphes), and (2) the unicommissural unicuspid aortic valve in which adjacent cusps of two commissures are congenitally fused. In the majority of cases, the only functional commissure is the left-non coronary, which originates an eccentric orifice in the shape of a teardrop that extends towards the left, posterior to the annulus, resembling an “exclamation mark”.

Patients with unicuspid aortic valve, as occur in cases of BAV, are at higher risk of infective endocarditis and aortic dissection. This is especially true for unicommissural valves, and symptoms appear once calcification occurs (Figs. 7.9 and 7.10). It is commonly associated with leaflet dysplasia. Accomisural valves are often associated with aortic atresia and hypoplastic left heart syndrome.

Fig. 7.9

Unicuspid aortic valve. The valve has a unique commissure (arrow) and extensive calcification. A 53-year-old male who died while playing raquetball. Severe LV hypertrophy (heart weight: 600 g). Severe coronary atherosclerosis affecting two vessels was also diagnosed (RCA and LAD coronary artery)

Fig. 7.10

Aortic stenosis and regurgitation in a unicuspid aortic valve. A 39-year old-male found dead at work. Severe cardiac hypertrophy was observed (heart weight of 924 g)

Acquired Pathology

Degenerative Calcific Aortic Stenosis

Degenerative calcific aortic stenosis is the most common type of valvular heart disease that requires valve replacement, and constitutes the valvulopathy that most frequently causes sudden death in older adults.

Morphologically, it is characterized by the deposition of nodular calcific masses on the leaflets, mainly at their base (Figs. 7.11 and 7.12A). The disease can be asymptomatic or result in left ventricular outflow obstruction, which causes a progressive increase in the LV pressure that in turn leads to concentric hypertrophy (Fig. 7.12b).

Fig. 7.11

Degenerative calcific aortic stenosis. A 54-year-old woman who was found dead at home. View of the aortic valve from the aortic side. Tricuspid valve with marked calcification (whitish nodules) at the base of the leaflets, with no commissural involvement. Necropsy also revealed moderate coronary atherosclerotic disease and severe cardiac hypertrophy

Fig. 7.12

Degenerative calcific aortic stenosis. A 74-year-old woman, with a history of chronic renal failure treated with haemodialysis, who died suddenly at home. (a) Tricuspid aortic valve with leaflet calcification. (b) Secondary concentric left ventricular hypertrophy. Heart weight: 495 g and wall thickness: 2 cm

Post-Inflammatory Aortic Stenosis

Inflammatory aortic valve disease has a mostly rheumatic origin and is associated with mitral valvulopathy (see below).

Fibrous thickening of the leaflets occur, which determines valve regurgitation in addition to stenosis, and commissural fusion (Fig. 7.13). With time, calcification may develop, initiating mixed types of aortic stenosis with features of degenerative and rheumatic stenosis (Fig. 7.14).

Fig. 7.13

Post–inflammatory aortic stenosis. Sudden death in a 57-year-old male with a previous history of osteomuscular problems, treated with NSAIDs. The aortic valve showed commissural fusion and calcification, which reduced the lumen to 7 mm in diameter (0.38 cm2). Heart weight: 570 g

Fig. 7.14

Mixed aortic stenosis. A 68-year-old male with hypertension. The aortic valve showed nodular calcification in the leaflets and commissural fusion (arrow). Mitral valve was also involved

7.2.1.2 Supravalvular Aortic Stenosis

Congenital supravalvular aortic stenosis is the least common form of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction. It usually manifests during childhood, and in some instances is part of Williams syndrome (also associated with characteristic facial anomalies, mental delay and hypercalcaemia).

Morphologically, the narrowing can be located in the sinotubular junction, creating an hourglass-type supravalvular stenosis (Figs. 7.15 and 7.16); or there can also be a diffuse narrowing for a variable distance along the ascending aorta (Fig. 7.17), or even in the aortic arch vessels. The leaflets tend to be dysplastic and it is often associated with a bicuspid aortic valve and coronary artery lesions.

Fig. 7.15

Supravalvular aortic stenosis associated with a bicuspid aortic valve. A 13-year-old boy diagnosed with bicuspid aortic valve underwent percutaneous valvuloplasty at the age of 9 years. During his last year the disease evolved to moderate aortic regurgitation and dilation and dysfunction of the LV. He died suddenly in a park. Image shows a bicuspid valve with thickened and rough leaflets (compatible with valvuloplasty), sinotubular junction stenosis, and post-stenotic dilation creating an hourglass deformity. Heart weight was 476 g, with a dilated LV and scar tissue from a circumferential subendocardial infarction

Fig. 7.16

Supravalvular aortic stenosis associated with a bicuspid aortic valve. A 12-year-old boy who died suddenly during physical education class. Morphologically, the aorta is similar to the above image (Image reproduced with permission from Suarez-Mier and Aguilera 2002)

Fig. 7.17

Supravalvular aortic stenosis of the tubular type. Sudden death in a 27-year-old woman with Williams’s syndrome. Note that the ascending aorta is tubular (2 cm in diameter) with a thickened wall. Dysplastic and dilated Valsalva sinuses (Image reproduced with permission from Suárez-Mier and Morentin 1999)

7.2.1.3 Subvalvular Aortic Stenosis

Subvalvular aortic stenosis (subaortic stenosis) affects 0.1/1,000 live births and is more common in the male gender. It is associated with other malformations such as BAV, ventricular septal defects, patent ductus arteriosus or coarctation of the aorta. Morphologically, there are three types (Table 7.1): thin membranous type (90 % of the cases), tunnel type and fibromuscular collar type that relates to obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with extensive hypertrophy in the anterior portion of the basal septum (see Chap. 8). It can also be caused by abnormalities in the mitral valve implantation.

It has been regularly observed that this type of obstruction develops and progresses over time, so for many experts this is an acquired rather than a congenital valvular disease.

The membranous type implies the formation of a fibrous membrane that extends from the interventricular septum onto the anterior leaflet of the mitral valve (Figs. 7.18 and 7.19). The clinical presentation ranges from a stable and asymptomatic disease that can last for many years to a rapidly progressive disease. It is frequently associated with aortic regurgitation and infective endocarditis and can relapse after surgical resection.

Fig. 7.18

Membranous subaortic stenosis. A 36-year-old male with a history of subaortic stenosis. He died of ischaemic cardiopathy with a three vessel disease and occlusive thrombosis in the RCA. A fibrous membrane can be appreciated below the aortic valve annulus that reaches the anterior leaflet of the mitral valve (arrow)

Fig. 7.19

Membranous subaortic stenosis. A 52-year-old male, diabetic, with no cardiac history, who died while sleeping. Heart weight: 724 g. View of the LV outflow tract where a subaortic fibrous membrane can be appreciated associated with an anomalous mitral valve, with shortening of the chordae tendineae of the anterior pillar (arrow)

7.2.2 Aortic Regurgitation

Aortic regurgitation is produced when the aortic valve does not close adequately. The acute form may be seen in cases of type A aortic dissection or valve disease due to endocarditis. The chronic form, which is more frequent, is due usually to valve pathology or aortic annulus distortion caused by dilation in the ascending aorta. Table 7.2 describes the classification of aortic regurgitation based on the mechanism.

Table 7.2

Types of aortic regurgitation

Type I: Dilation of the aortic root with normal cusps and normal motion (in patients over 60 years it is idiopathic or associated with hypertension; in younger patients it is related to Marfan syndrome) |

Type II: Secondary to valve prolapse with mixoid or excessive tissue and commissural disruption |

Type III: Secondary to restricted cusp motion with valve structural lesions (rheumatic valve disease, endocarditis, bicuspid valve, etc.) |

The most frequent causes of aortic regurgitation in the Western world are secondary to aortic dilation and bicuspid valve involvement. The pathology of the aorta is described in Chap. 3.

7.3 Mitral Valve Pathology

Normal function of the mitral valve requires the structural integrity of all its components. Table 7.3 summarises the macroscopic and microscopic features of the mitral valve (see Chap. 1).

Table 7.3

Anatomy of the mitral valve

Semicircular anterior leaflet: |

Rough zone that coapts with the posterior leaflet |

Smooth zone |

Fenestrated posterior leaflet with indentations |

Rough zone that coapts with the anterior leaflet |

Membranous zone |

Basal zone |

Anterolateral and posteromedial commissures |

Tendinous cords (Chordae tendinae) |

Atrialis: thin layer of aligned elastic and collagen fibres in continuity with the left atrial endocardium |

Spongiosa: composed of mixoid connective tissue |

Fibrosa: composed of dense collagen with some elastic fibres |

Fig. 7.20

Normal mitral valve. (a) Closed valve as seen from the left atrium. PMC: posteromedial commissure. ALC: anterolateral commissure. (b) Open valve. (c) Microscopic image of the posterior leaflet and chordae tendinae at low magnification (Weigert’s stain) (d) Higher magnification of the edge of the posterior leaflet: A atrialis, S spongiosa, F fibrosa (Masson’s trichrome)

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree