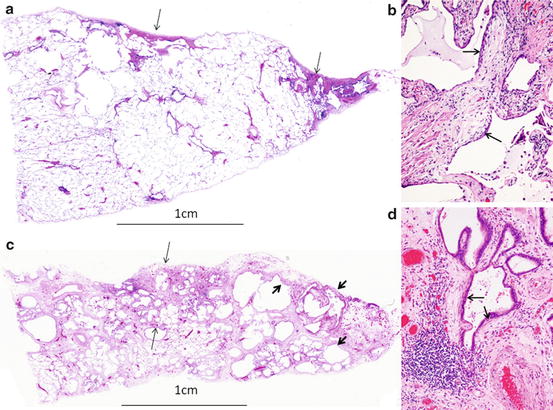

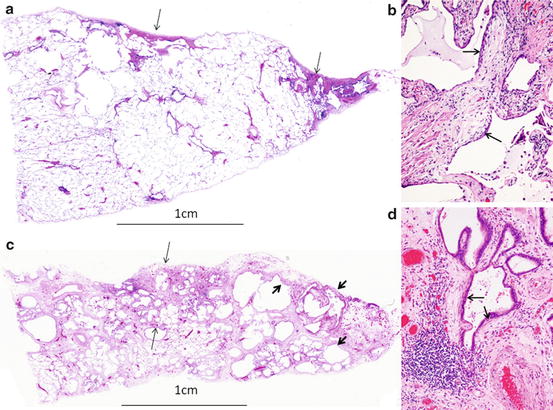

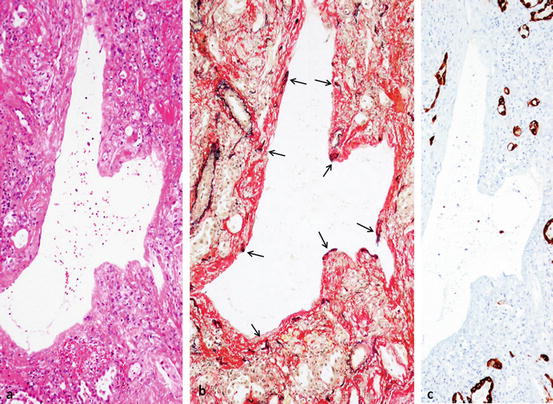

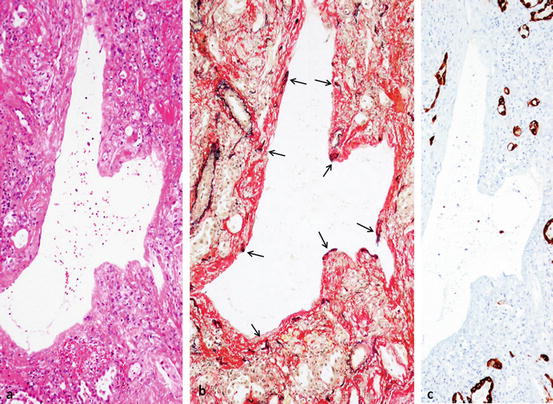

Fig. 7.1

Histology of UIP. (a) Panoramic view. Patchy involvement and perilobular dense fibrosis with structural remodeling. Bar: 1 cm. Hematoxylin-eosin staining (HE). (b, c) Fibroblastic focus on dense fibrosis (arrow). ×10. HE

Now (in 2011), we can understand that UIP (HRCT and/or histology) of unknown etiology is IPF [10]. In 2000, IPF was defined as follows: (a) unknown etiology, (b) abnormal pulmonary function (decreased vital capacity and/or impaired gas exchange) with decreased diffusing capacity, and (c) abnormality on conventional chest radiographs or high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) (bibasilar reticular abnormalities with minimal ground-glass opacities on HRCT) when surgical lung biopsy (SLB) proved UIP [9]. Clinical criteria of IPF without SLB were defined separately. Recently, typical HRCT findings (honeycombing) have been stressed (previous criteria [9] including dyspnea and abnormal pulmonary function were eliminated), and SLB was recommended when HRCT is not typical [10]. In the latter cases [10], complicated combinations of HRCT and SLB can diagnose IPF as definite, possible, or inconsistent. Histopathological criteria for UIP were divided into (a) definite (fulfills the four criteria: marked fibrosis with structural remolding predominantly located peripheral lobule, patchy involvement, FF, and no alternative diagnosis), (b) probable (marked fibrosis but lacking either patchy involvement or FF and no alternative diagnosis), (c) possible (marked fibrosis and no alternative diagnosis), and (d) not UIP [10].

Not UIP includes the presence of any of six criteria: (a) hyaline membranes, (b) organizing pneumonia, (c) granulomas, (d) marked inflammatory cell infiltration away from honeycombing, (e) predominant airway-centered changes, and (f) features suggestive of an alternative diagnosis. Features suggestive of an alternative diagnosis can include silicotic nodules, asbestos bodies, substantial other inorganic dust deposits, and marked eosinophilia [1].

7.3 Natural History of UIP, Emphasizing the Early Stage and Exacerbation

Natural history of UIP will be presented in Fig. 7.2 and will be explained later. In short, its continuous gradual progression and acute and subacute exacerbation will take place at any stages of UIP. Clinical IPF is the last stage.

Fig. 7.2

Suspected natural history and treated course of UIP. Natural history of UIP (thick line) is divided into three stages: (1) undetectable stage; (2) asymptomatic, HRCT-detectable, subclinical stage; and (3) symptomatic, clinical stage. Acute exacerbation (blue) can be seen at any stage and some cases respond to corticosteroid therapy (red arrow). When acute exacerbation is seen at the undetectable stage, it is called acute interstitial pneumonia or idiopathic DAD (yellow arrow). Subacute exacerbation (purple) can be seen at any stage and most cases respond to corticosteroid therapy (red arrow). Slower progression than expected is also seen (dark blue) (Modified from Modern Physician (Ref. [38]), Internal Medicine [43], and Kokyu [49] with permission)

7.3.1 Definition of IPF

It is unclear to me whether IPF without dyspnea is admitted into the new classification [10], though many Japanese specialists believe so. In order to avoid confusion, here I wish to use the terms subclinical (asymptomatic stage but sufficiently detectable by HRCT) IPF and clinical (symptomatic stage, ordinarily) IPF when the cause of UIP is unknown.

7.3.2 Natural History of UIP

7.3.2.1 Stage

I suspect that UIP starts with microscopic dense fibrosis with FF generally located in the base of the lower lobe subpleurally (Fig. 7.3a, b). Gradually, this fibrosis extends upward and to the inner lung continuously or discontinuously until HRCT can detect it (Fig. 7.3c, d).

Fig. 7.3

Histology of early UIP. a.c. Costophrenic edge on the right side. (a) Microscopic UIP showing dense fibrosis with/without structural remodeling (arrow). Bar: 1 cm. Panoramic view. HE. (b) Fibroblastic focus on dense fibrosis (arrow). ×10. HE. (c) Histology of macroscopic mild UIP showing dense fibrosis of 4.5 mm thickness from the pleura (between arrows) with honeycombing (thick arrows). Panoramic view. HE. (d) Fibroblastic focus on dense fibrosis (arrow). ×10. HE

I personally defined the UIP stages as follows: (a) microscopic stage, when macroscopically undetectable; (b) mild macroscopic stage, macroscopically detectable but up to 1 cm in depth from the pleura; and (c) extensive macroscopic stage, more than 1 cm in depth from the pleura by macroscopic examination of resected lung [13–15]. The mild macroscopic stage roughly correlates with the HRCT-detectable stage when there are faint or clear, sufficient reticular shadows and/or honeycombing. When bilateral lower lobe reticular shadows or honeycombing are clearly seen within 1 cm in depth, it is subclinical IPF. The extensive macroscopic stage might be roughly clinical IPF.

7.3.2.2 Incidence and Time Course

It is unclear how many years are required to progress from onset until the mild macroscopic stage, although 10 to 20 years has been suggested by me. The incidence of macroscopically detectable mild- and extensive-staged UIP was more than 20 % in more-than-moderate smokers and 3.5 % in nonsmokers in lungs subjected to lobectomy for lung cancer [14]. The incidence of mild macroscopic UIP increases with age (0 %, <40 years; 3 %, 50–60; 14.1 %, 70–80; 28 %, >80) [13]. It seems that mild macroscopic UIP begins approximately at the age of the 40s. The rate of subclinical interstitial pneumonia (mainly subclinical IPF) was 9.7 % [16] in Japan. In addition, a rate of bilateral lower lobe reticular shadows of 8 % was reported, as determined by HRCT in asymptomatic smokers [17]. I suppose that both variously typed interstitial pneumonias and airspace enlargement with fibrosis (AEF) [14] are included in this 8 %. As for progression, Nagai et al. reported that routine chest X-ray-screened, pathologically proven UIP cases became symptomatic 1000 days later [18]. Fukushima et al. followed up 127 microscopic and macroscopic mild UIP cases for 4 years; 4 % showed acute exacerbation and 6 % showed chronic progression [19]. It is necessary to follow up cases that show HRCT-detected reticular shadows and macroscopically detected UIP lesions found by lobectomy to determine how many years are required for progression to clinical IPF.

7.3.3 Acute Exacerbation of UIP

7.3.3.1 Historical Understanding

DAD superimposed of UIP is clinically called acute exacerbation [20–30], whether UIP is idiopathic or secondary. Liebow might have been the first to report acute exacerbation of IPF [5]. In Japan, idiopathic interstitial pneumonia was divided into the acute form (idiopathic DAD) and the chronic form (IPF) in 1976 following Liebow’s concept because of the common complication of DAD in UIP. Yoshimura et al. reported acute exacerbation of IPF for the first time in 1984 [20]. Thirty-five cases suffered 43 episodes of acute exacerbation, and 97.1 % had died one month after the episode. They proposed diagnostic criteria of acute exacerbation. Kondo and Saiki published the first English paper in 1989 [21]: (a) clinical study (among 155 IPF cases, 89 (57 %) showed acute exacerbation) and (b) pathological study (among 22 SLB-proved IPF cases, four showed acute exacerbation, and pathological examination confirmed hyaline membrane formation (one type of DAD) on UIP in all of these four cases).

7.3.3.2 General Risk Factors and Incidences

Papers on acute exacerbation were mainly reported from the northeast of Asia, and the incidence of acute exacerbation varied, but was around 10 % per year [20, 22–25]. Risk factors were infection, reduction of corticosteroid dose, and various types of surgery, among others [15, 20–22, 25]. The reported incidences of acute exacerbation of clinical and subclinical IPF following lobectomy for lung cancer are 15 % (collective data of nine papers) [26] and 15.8 % (11 papers) [27]. The incidences of acute exacerbation of microscopic and macroscopic mild and extensive UIP cases just after lobectomy were 1.6, 6, and 10.6 % [15]. The incidence of acute exacerbation following SLB was reported to be low in Europe and America [28, 29].

7.3.3.3 Extension of Acute e Exacerbation to the Milder Cases and Mortality

Generally, the concept of acute exacerbation has been used for clinical IPF. We reported acute exacerbation of macroscopic mild UIP cases following lobectomy in 2001 [13] and again in 2005 [15], in the same year as the report of Chida et al. [30], as well as a case report in 2011 [31]. We also reported acute exacerbation of the microscopic-staged cases [15, 32].

7.3.3.4 The Pathological Risk Factors

The pathological risk factors of acute exacerbation have not been well clarified. Fukushima et al. compared a thick-walled, small-sized honeycombing (4.3 ± 0.5 mm in diameter) cases and a thin-walled, variously sized honeycombing (10.0 ± 1.6 mm in diameter) cases. The former cases showed a higher incidence of acute exacerbation, as well as higher rates of women, nonsmokers, and those with a lower smoking index [34]. We also confirmed that the former cases showed a higher incidence of acute exacerbation, in addition to extent by another trial [15]. Histological factors related to acute exacerbation was the presence of active inflammatory changes: (a) degree of interstitial inflammation continuous with dense fibrosis, (b) amount of granulation tissue in and next to dense fibrosis (FF), (c) quantification of interstitial inflammatory change with granulation tissue apart from dense fibrosis, and (d) quantification of acute interstitial inflammatory change with fibrin exudation seen in the lobectomy UIP area [35]. In addition, a microscopic organized membranous organization pattern of DAD, which will be described later, was seen only in the acute exacerbation cases [35].

7.3.3.5 Two Histological Types of DAD

According to my experience, two histological patterns of DAD are observed. One is extensive epithelial erosion and hyaline membrane formation with subsequent membranous or ring organization (hyaline membrane was replaced by membranous granulation tissue due to activation of fibroblast) over the orifice ring of the alveolar wall (Fig. 7.4), and the other is epithelial erosion and massive exudation of fibrin following subsequent obstructive and incorporated-type intraluminal organization (Fig. 7.5) [36]. I named these as follows: (a) membranous organization pattern and (b) luminar organization pattern (somewhat resembling OP) in 1992 and 1994 [37, 38] (Figure 7.6 with permission from Kokyu and Modern Physician). Frequently, both patterns and mixed pathology are seen in autopsy lungs, especially cases without a fulminant course, and the luminar organization pattern is older than the membranous organization pattern. DAD pathology as reported by Kondoh et al. was a luminar organization pattern [33]. Mandal et al. reported that DAD with organizing pneumonia showed greater survival than DAD without it (67 % versus 33 %) [39]. A luminal organization pattern and DAD with organizing pneumonia might involve nearly the same pathology. Parambil et al. reported seven cases showing DAD (six cases) and OP (one case) with 86 % mortality [40]. Churg et al. reported 12 cases showing DAD (four cases), OP (five cases), and giant fibroblastic foci (three cases), ten cases of which survived due to therapy [41].

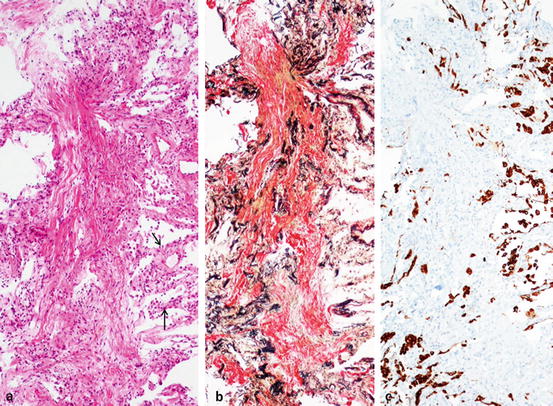

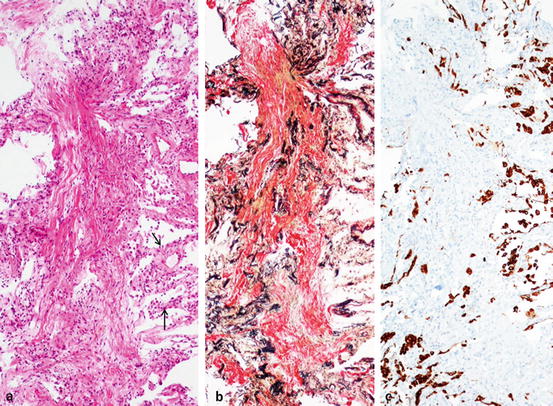

Fig. 7.4

Organizing DAD, membranous organization. ×10. (a) Membranous or ring organization and dilated space. HE. (b) Alveolar orifice (arrows, portion of black dot) is embedded in the membranous organization and alveolar lumina are markedly collapsed. Dilated space is alveolar sac or duct. Elastica-van Gieson staining (EvG). (c) Remaining tiny airspace (mainly collapsed alveolar lumen) is lined by regenerative epithelium but no epithelialization on sac or duct. Immunostaining with AE1/AE3 for epithelium

Fig. 7.5

Organizing DAD, luminar organization. ×10. (a) Longitudinal organization in the center and thick-walled surrounding alveolar wall with cuboidal metaplasia (arrow). HE. (b) Many collapsed obliterated alveoli are trapped in the organization (obstructive-type organization). EvG. (c) No epithelialization in the organization, but surrounding alveolar wall is lined by cuboidal cells. Immunostaining with AE1/AE3 for epithelium. Figures 7.4 and 7.5 are of the same case. A 66-year-old female complained of exertional dyspnea and diffuse ground-glass opacities (GGO) within 1 month. Transbronchial lung biopsy showed luminal organization. Later, necropsy showed both membranous organization and luminal organization. The type of DAD changed or progressed

Fig. 7.6

Two types of DAD. Membranous organization begins with hyaline membrane formation covering the surface of the alveolar orifice, and then hyaline membrane undergoes organization, resulting in a membranous or ring organization. Luminar organization begins with massive exudation to the alveoli, and obstructive and mural organization firmly attached to the alveolar wall

7.3.3.6 Three Histological Features of Acute Exacerbation and Histological Differences Might Be Related to Prognosis

Before writing about pathology of acute exacerbation, I wish to discuss acute lung injury patterns (ALI/P). ALI/P was proposed by Katzenstein including DAD and BOOP in 1997 [42]. As far as my understanding from English literatures, the distinction between organizing DAD (luminal organization pattern) and OP is not so clear to me. The intraluminal organization seen in DAD is obstructive and incorporated mural pattern with an unclear lung structure, and the intraluminal organization in OP is mainly of the polypoid type with a preserved lung structure. Histologically, differential diagnosis between DAD and OP is clear, but there is a transitional-typed organization between DAD and OP. I named this ALI/P not otherwise specified (NOS). Katou et al. also reported this type of acute exacerbation [43]. Table 7.1 presents the histological features and prognosis of the two types of DAD and ALI/P NOS. Nowadays, above three comprise pathological features of acute exacerbation.

Table 7.1

Histological features and prognosis of acute exacerbation

Early, acute stage | Organizing stage | Prognosis | |

|---|---|---|---|

DAD membranous organization | Mainly hyaline membrane formation | Membranous/ring fibrosis on hyaline membrane with remodeled lung structure | Poor, mostly fatal |

Epithelial denudation | Atypical epithelial regeneration including stratified squamous cells | ||

Fibrin exudation | |||

Hemorrhage | |||

DAD luminar organization | Mainly fibrin exudation | Obstructive and mural organization with unclear lung structure | Frequently favorable |

Epithelial denudation | Atypical epithelial regeneration | ||

Myxomatous swelling of the alveolar wall | |||

ALI/P NOS | Not clear | Various types and degrees of organization with unclear or preserved lung structure | Favorable |

Diffuse interstitial inflammation | |||

Epithelial regeneration |

As stated before, the mortality rate of acute exacerbation ranges from 0 to 100 %. This difference in the mortality rate might mainly depend on different histology, in addition to recent advanced therapy, and other factors.

7.3.4 Subacute Exacerbation of UIP

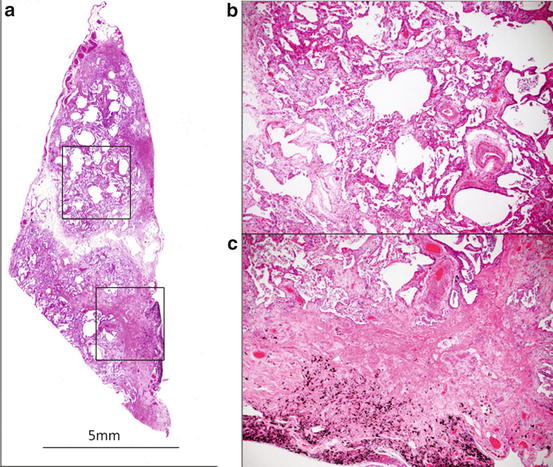

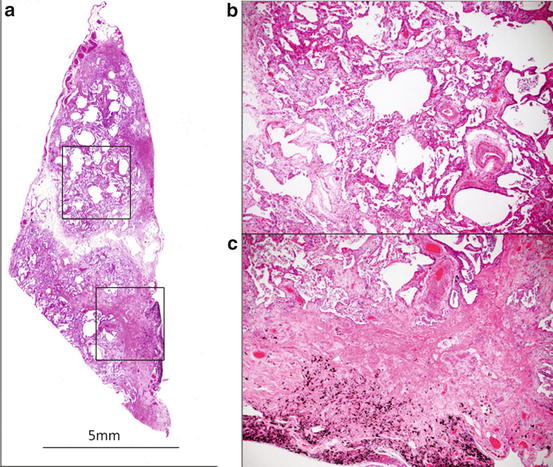

We reported on female-dominant subacute interstitial pneumonia (SIP) [44] with 1 month to 6 months of increasing dyspnea, which shows a favorable prognosis following steroid treatment in 1995, 1 year after the NSIP paper [45]. Histologically, SIP resembles cellular and fibrosing NSIP (c- & f-NSIP) [45], but differs from organizing pneumonia [2]. I wish to propose the descriptive pathological term “organizing interstitial pneumonia” (organizing IP; interstitial pneumonia with various degreed and types of luminar organization) for SIP pathology. In addition, there was the frequent complication of UIP subpleurally together with SIP (15 cases, age 62.4 ± 9.3) (Fig. 7.7) in the same slide, which showed worse prognosis than SIP alone (35 cases, age 58 ± 11) in spite of no clinical and radiological differences between two groups [46]. This resembles subacute exacerbation of UIP cases. There are also reports on discordant UIP, namely, the presence of UIP and NSIP in different lobes, which follows the prognosis of IPF and has a worse prognosis than NSIP alone [47, 48].

Fig. 7.7

Combined fibrosing IP and UIP seen in a SLB slide. (a) Diffuse involvement of the lung tissue. Panoramic view. HE. (b) Inflammatory thick alveolar wall due to incorporation of organization into interstitium and new luminar organization (upper box). ×10. HE. (c) About 2-mm-thick, dense subpleural fibrosis with muscle tissue proliferation of UIP feature (lower box). ×10. HE

7.3.5 Scheme of the Natural History of UIP

Katou et al. and I proposed schemes of the natural history of UIP in 1994 and 1995 [38, 43, 49], and now I wish to present a modified natural history and treated course of UIP, with permission from the publishers (Modern Physician, Internal Medicine, and Kokyu) of references [38, 43, 49] (Fig. 7.2). Namely, it is divided into undetectable stage, subclinical stage, and clinical stage, as stated before. At any stage, acute exacerbation can take place. Araya et al. reported fatal [32], but Katou et al. reported improved acute exacerbation at the undetectable stage [44]. When acute exacerbation occurs at the undetectable stage, it is difficult to differentiate from idiopathic DAD (so-called acute interstitial pneumonia). We reported that the incidence of acute exacerbation at the undetectable stage following lobectomy is 1.6 % [15]. We also suspect that subacute exacerbation can take place at any stage (Fig. 7.7). Slower progression than expected is also experienced. The suspected progression pattern is shown in Fig. 7.8, namely, chronic, subacute, and acute (with permission from Modern Physician: [38]). Chronic progression comprises FF and local interstitial pneumonia with organization next to or adjacent to dense fibrosis. Subacute progression comprises two types of subacute exacerbation (c- & f-NSIP and organizing IP) and may be cellular NSIP (c-NSIP) apart from dense fibrosis.

Fig. 7.8

Three patterns of UIP progression. Generally, UIP progression is chronic, characterized by fibroblastic focus formation and other injury patterns next to fibrosis or the nearby perilobular area. Subacute progression sometimes takes place, showing interstitial pneumonia with some luminar organization apart from dense fibrosis. Acute exacerbation shows both luminar organization and membranous organization of DAD or ALI/P NOS. Generally, luminar organization takes place first, followed by membranous organization. In fulminant cases, only hyaline membrane formation occurs, and death occurs without membranous organization (Modified from Modern Physician (Ref. [38]), with permission)

The complication of two types of DAD, AIP/P NOS, c-NSIP, c- & f-NSIP, and organizing IP might be an integral part of UIP (concept of stable or inactive phase of UIP when there is UIP only and unstable or active phase of UIP when there is UIP + another interstitial pneumonia).

7.3.6 Early HRCT Detection of UIP Can Prepare for Acute Exacerbation and Early Therapy

CT and HRCT features of IPF were reported [50, 51]. Johkoh et al. recently reported the HRCT features of clinical IPF without honeycombing [52]. However, we do not know about the HRCT features of subclinical IPF. Close pathological and radiological correlation is needed using lung subjected to lobectomy showing macroscopic mild UIP or subclinical IPF. It would be useful to understand the characteristic HRCT features of subclinical IPF, so we can prepare for acute and subacute exacerbation, especially choosing therapy methods for lung cancer and introducing prompt timely therapy. I used to report to clinicians on whether lobectomized UIP cases had a risk of acute exacerbation or not by checking the activity of UIP as described before within 1 week, since most postoperative acute exacerbations occur around 1 week after surgery (unpublished data).

As discussed before, many of acute exacerbations are suspected to begin with luminar organization-typed DAD or ALI/P NOS; then early vigorous therapy can be effective.

7.4 Differential Diagnosis of UIP and Etiological Approach Through Histology

7.4.1 Classification of Interstitial Pneumonias

The classification of interstitial pneumonias is an artificial one, and there was no complete classification. We thus have to look for a more suitable classification that shows the clinical-radiological-pathological correlation and indicates the constant effect of therapy.

Carrington et al. proved the differences in the natural history and treated course between UIP and DIP [7]. However, DIP was interpreted as the early stage and UIP as the late stage of IPF in 1976 [53], which was officially corrected in 2002 [1].

In my opinion, interstitial pneumonias of various etiologies can be classified into three types: acute interstitial pneumonia (using just the pathological pattern, not the specific disease) within 1 month, SIP with a course of 1–6 months of symptoms, and chronic interstitial pneumonia with a course of more than 6 months of symptoms or radiological findings [37, 49, 54]. Acute interstitial pneumonia can be histologically divided into membranous organization and luminar organization of DAD and ALI/P NOS. SIP can be histologically divided into organizing IP, c-NSIP, and c- & f-NSIP (overlap each other). Chronic interstitial pneumonia can be histologically divided into UIP, c- & f-NSIP, fibrosing NSIP (f-NSIP), DIP, and just chronic interstitial pneumonia unclassifiable.

Various types of SIP can be reversible. The challenge to the pathologists is chronic interstitial pneumonia; each histology has its own course and therapy response. Differentiation is essential for the selection of therapy.

7.4.2 Histological Heterogeneity of UIP and Selection of SLB Site

7.4.2.1 Histological Heterogeneity

As stated before, Flaherty et al. reported that, among 109 cases (either UIP or NSIP), biopsied multiple lobes showed UIP-UIP in 47 %, UIP-NSIP in 26 %, and NSIP-NSIP in 27 % [47]. Monaghan et al. reported that among 64 previously diagnosed IPF cases, 12.5 % showed UIP-NSIP, 39.1 % showed UIP-UIP, and 48.4 % showed NSIP-NSIP [48]. I wonder whether the UIP-NSIP group showed pure UIP-pure NSIP without mixed features in one slide. In both studies, the age of UIP-NSIP cases was intermediate between those of UIP-UIP cases and NSIP-NSIP cases. Our SIP + UIP cases are old (not statistically significant) compared with SIP only. I suspect that, in the UIP-NSIP group, UIP might have a macroscopic mild extent and NSIP might be complicated, which could explain why the patients are younger than those with UIP-UIP and show symptoms. Katzenstein et al. also stated that focal NSIP was frequently seen in UIP [11, 12]. The data indicate that mixed histological patterns frequently exist, even in one disease, and the complication of NSIP can be understood as chronic exacerbation of UIP/stepwise progression of it or subacute exacerbation.

7.4.2.2 Effect of Therapy

Treatment also affects histological features. Matsushima reported that SLB-proved DIP following treatment showed NSIP by later lobectomy for lung cancer [55]. Generally, at an advanced stage, each pathological pattern loses its characteristic or specific features and becomes nonspecific with/without therapy.

7.4.2.3 Selection of Biopsy Site and Management

In order to make a pathological diagnosis, clinicians have to avoid far-advanced areas and should choose mildly to moderately affected areas, including normal-looking lung or early-stage areas. If possible, clinicians should select two portions showing different features on HRCT. In addition, the tip of the middle lobe or lingula should be avoided because of many nonspecific changes. Afterward, SLB staple should be removed and formalin should be injected, until the pleural surface becomes smooth, through the staple-removed area, in order to avoid injection of formalin into a fibrotic portion and interlobular septum.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree