General

Endocardial cardiac ablations are performed for a variety of indications. These include ablation of bypass tracts, re-entrant pathways, and arrhythmogenic foci determined by electrophysiologic mapping (

Table 142.1). Arrhythmias that are treated include atrial and ventricular tachycardias and atrial fibrillation.

Ablation is most frequently accomplished by radiofrequency waves, but lasers, microwaves, and cryoablation have also been used. Radiofrequency causes thermal injury using alternating current and is usually delivered percutaneously via catheter. Cryoablation produces myocardial injury with tissue freezing and thawing. Cryoablation, which is more frequently done by open procedure, produces less endothelial or endocardial injury possibly with less endocardial thrombus.

An electrophysiologic study records electrical activity and determines where catheter ablation may eliminate cardiac arrhythmias. The success of catheter ablation is high for atrioventricular nodal reentry, accessory pathways, atrial flutter, and idiopathic ventricular tachycardia. The success rate is lower in patients with atrial fibrillation or structural heart disease.

5

Wolff-Parkinson-White Syndrome

Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome is a preexcitation syndrome caused by atrioventricular bypass tracts that are most common in the left free wall, followed by the right free wall and the posteroseptal region (see

Chapter 4). Most patients are asymptomatic and do not require treatment. Catheter ablation is performed in patients who are refractory to drugs and are symptomatic with atrioventricular reentrant tachycardia or paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. In the past, open surgical procedures were performed to interrupt the pathway, and currently, catheter-based radiofrequency ablation is used, with a success rate of near 100%.

6Of note, patients with certain types of congenital heart disease (e.g., Ebstein anomaly) (Chapter 34) have a high incidence of WPW and may have ablations in addition to their underlying structural heart disease.

Atrial Arrhythmias

Supraventricular arrhythmias are frequently treated with ablation and are often caused by reentry, especially near the coronary sinus. Of atrial arrhythmias in children, supraventricular re-entrant tachycardia

accounts for over 60%, the remainder including atrioventricular nodal re-entrant tachycardia, atrial tachycardia, and atrial flutter.

7,8,9 Supraventricular tachycardias also occur in adults, and ablation sites can be anywhere in the atria but most frequently in the area of the atrioventricular node and posteriorly at the coronary sinus. In junctional reciprocating tachycardia, the accessory pathway is often the posteroseptal area.

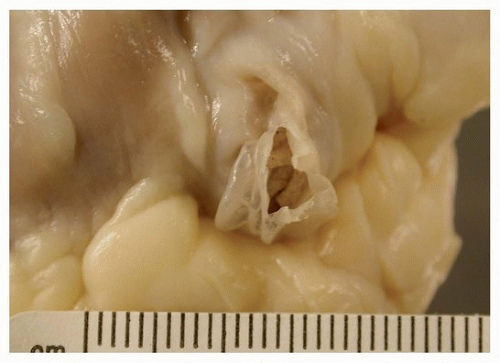

10 Occasionally, they may be associated with coronary sinus aneurysms (

Fig. 142.4).

Atrial flutter is classified as counterclockwise or clockwise and is a re-entrant arrhythmia, which often involves the isthmus between the tricuspid valve and the inferior vena cava; this area is used for treatment of atrial flutter, and ablation sites may be present in this area at autopsy from patients with prior treatment.

Atrial fibrillation is the most common arrhythmia treated by intervention. It may be chronic or paroxysmal and is frequently associated with organic heart disease, such as cardiomyopathy or ischemia. Chronic atrial fibrillation has been classified as persistent (>7 days) or permanent. Occasionally, there are no predisposing diseases (lone atrial fibrillation). Noncardiac conditions that increase the risk of atrial fibrillation include hypertension, lung disease, and hyperthyroidism. The most common cardiac conditions are mitral valve disease, especially stenosis, ischemic heart disease, and cardiomyopathy.

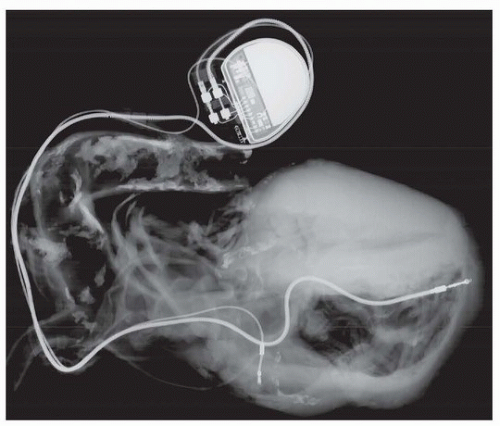

Patients with atrial fibrillation are treated with anticoagulation, because there is a sevenfold increase in the risk of stroke from embolized mural thrombosis. Other complications include heart failure and palpitations; the ventricular response is treated with beta-blockers and calcium channel blockers. Occasionally, ablation of the atrioventricular node is necessary, with dual-chamber pacing.

There are no specific pathologic findings in atrial fibrillation, but nonspecific features are commonly encountered such as gross atrial dilatation (which may be primary or secondary to the arrhythmic state) and histologic hypertrophy and fibrosis. These latter findings have been shown to have some correlation with recurrence of atrial fibrillation following the Cox maze procedure.

11 Mural thrombi are common findings in markedly dilated atria.

The arrhythmia is believed to propagate in the area of the pulmonary valve sleeves, or regions of smooth muscle that extend from the pulmonary vein media into the left atrial body. The sleeve length ranges from 2 to 25 mm and is longest in the upper veins. The concept of interruption of left atrial tracts has led to a variety of surgical approaches, which are generally termed “maze” procedure, after the irregular incisions made above the posterior leaflet of the mitral valve. Patients with atrial fibrillation due to mitral valve disease often undergo mitral valve replacement or repair. Approximately 40% of these patients have surgical ablation either by incisions or by other methods of ablation, typically cryotherapy (cryomaze). The latter procedure has been associated with over 75% freedom from recurrent atrial fibrillation at 1 year.

12 In general, the success of the maze procedure is correlated to the degree of atrial dilatation and is most successful if the atrium is <50 mm in diameter.

Ventricular Tachycardia in the Absence of Structural Heart Disease

Monomorphic ventricular tachycardias and premature ventricular impulses occur anywhere in the ventricles but most frequently in the left ventricular outflow tract beneath the aortic valve cusps,

13 right ventricular outflow tract,

14 and tricuspid annulus.

15 Ablation has a good success rate of ameliorating symptoms with prevention of recurrent arrhythmias. In patients with a history of ventricular ablation, these are sites that are likely to have been treated with prior ablations, which appear as white endocardial scars.

Ventricular Tachycardia in Structural and Ischemic Heart Disease

Cardiomyopathies, including hypertrophic and dilated cardiomyopathy, are prone to the development of monomorphic ventricular tachycardias that are amenable to ablation.

16 In dilated cardiomyopathy, they may be endocardial based, especially near a valve annulus, or deep and subepicardial.

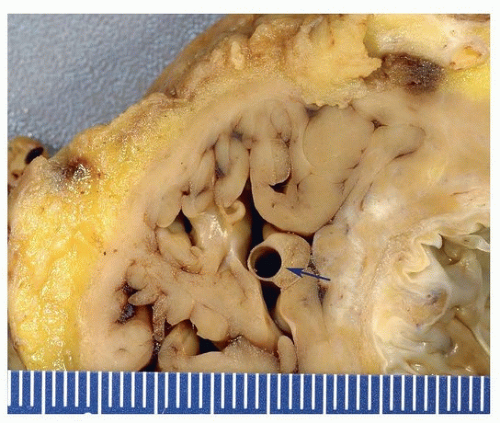

17 The latter may be approached percutaneously by introducing the catheter to the epicardium through the pericardium. Ventricular tachycardia associated with healed myocardial infarction is also associated with areas of low-voltage scar. Histologic sections of these areas at autopsy show transmural scars in most cases.

18 Common ablation sites for monomorphic ventricular tachycardias in ischemic cardiomyopathy are the posterior papillary muscle and ventricular septum.

19

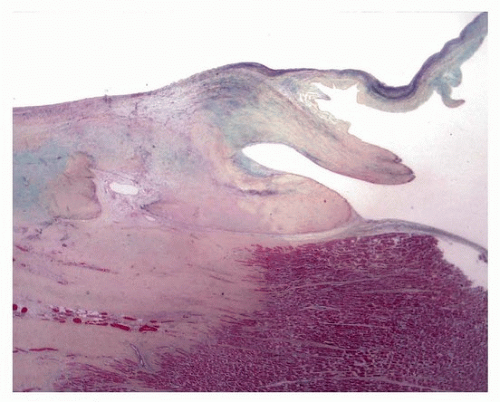

Pathologic Findings

Radiofrequency ablation results in endocardial injury generally 5 to 6 mm diameter and up to 3 mm deep, sometimes associated with mural thrombus. Grossly, lesions are acutely pale and progress to fibrosis, which may disappear on gross inspection. Acutely, there is coagulative necrosis surrounded by neutrophils and then macrophages and granulation tissue, as in any wound healing response. In areas of healed injury, there may be transmural coagulation necrosis of meshlike fibrotic tissue, with interspersed islands of myocardial cells, up to a maximum depth of 7 mm.

18 Chronically, there is fibrosis, which is nonspecific as to etiology.