SWS is predominant during the first third of the sleep cycle, these disorders are more prevalent in the beginning of the night and are common in childhood— usually decreasing in frequency with increasing age (11,12). Arousal disorders may be triggered by a variety of conditions including fever, alcohol use, sleep deprivation, emotional stress, or medications. These precipitators should be viewed as triggering events in susceptible individuals rather than causal. A variety of primary sleep disorders such as obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) may also provoke disorders of arousal (13).

CNS depressants (i.e., hypnotics, sedatives, tranquilizers, alcohol, and antihistamines); and underlying metabolic, hepatic, renal, and toxic encephalopathies. Confusional arousals are often seen in conditions characterized with pathologic hypersomnia, such as in patients with narcolepsy or OSA. Episodes of confusional arousals are frequent in patients with sleep terrors and sleepwalking. Organic causes of confusional arousals are rare but may include lesions in arousal generators, such as the periventricular gray, the midbrain reticular area, and the posterior hypothalamus.

TABLE 5.1 Key Similarities and Differentiating Features Between Non-REM and REM Parasomnias as Well as Nocturnal Seizures | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

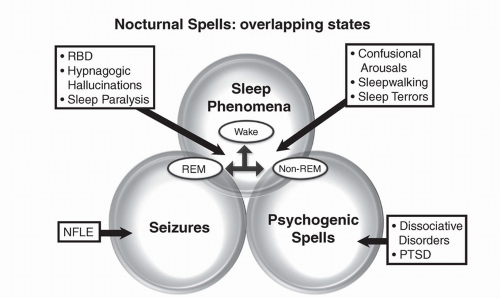

1. Sleep terrors are differentiated by symptoms of acute autonomic hyperarousal and fear.

2. Sleepwalking includes ambulation and complex motor automatisms.

3. RBD consists of dream enactment and complex movements such as fighting and punching while asleep in older male patients.

4. Sleep-related epileptic seizures of the partial complex type with confusional automatisms are rare, are diurnal, and associated with an epileptic EEG pattern.

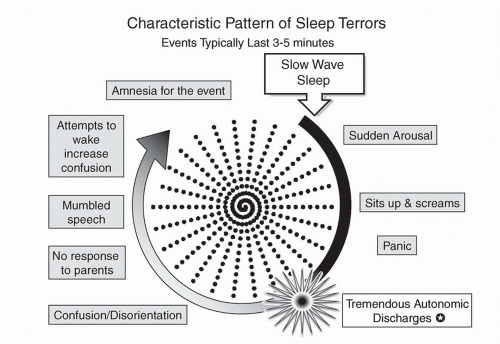

1. Sleep terrors: Sleepwalking episodes are distinguished from sleep terrors in that the latter are often accompanied with an attempt to “escape” from the terrifying stimulus and have an associated autonomic hyperarousal, such as fear, and panic coupled with a scream and aggression (Fig. 5.4).

2. RBD: RBD is characterized clinically based on episodes during REM sleep of complex dream-enactment, fragmentary recall, and abnormal augmentation of muscle activity.

3. Sleep-related epilepsy with ambulatory automatism: Can be distinguished by an epileptiform EEG.

4. Nocturnal eating syndrome: Characterized by ambulatory behavior of eating.

TABLE 5.2 Differences Between Sleep Terrors and Nightmares | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

1. Nightmares: Differentiation from nightmares is most important (Table 5.2). Sleep terrors are characterized by amnesia of the event compared to the vivid recollection in patients with nightmares. Nightmares also occur during the last third of the night, but unlike sleep terrors, they are confined to REM sleep. Associated with a vivid recollection and normal cognition, nightmares usually lack the sympathetic activation and confusion that is frequent with sleep terrors.

2. Confusional arousals: Are awakenings from SWS without terror or ambulation.

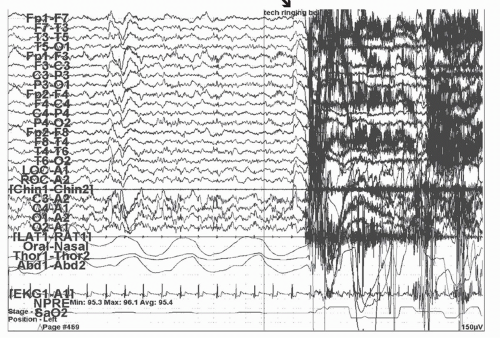

3. Sleep-related epilepsy: Episodes tend to be more frequent, occur several times per night, and have ictal abnormalities on the PSG/EEG recordings.

4. OSA: Patients to have phenotypic evidence of crowded airways, snoring, and evidence of apneic episodes associated with oxygen desaturations on PSG.

to 5 have clinically significant nightmares that disturb their parents. Up to 75% of the population can remember at least one or a few nightmares in the course of their childhood. About half of adults admit to having an occasional nightmare. About 1% of the adult population is afflicted with frequent nightmares of more than one per week. Nightmares usually start at age 3 to 6 years but can occur at any age. In children, the gender ratio is equal, while in adults there is a male: female ratio of 1:2 to 1:4 favoring females.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree