Paraesophageal Hernia Repair: Laparoscopic Technique

John G. Hunter

Mark J. Eichler

DEFINITION

For millennia, the existence of hiatal hernias was well known. First described by Henry Bowditch in 1853, and later in 1951 officially by Philip Allison, the paraesophageal hernia (PEH) presents a physiologic link to reflux esophagitis, ulceration, stricture, and other esophageal pathology.1,2

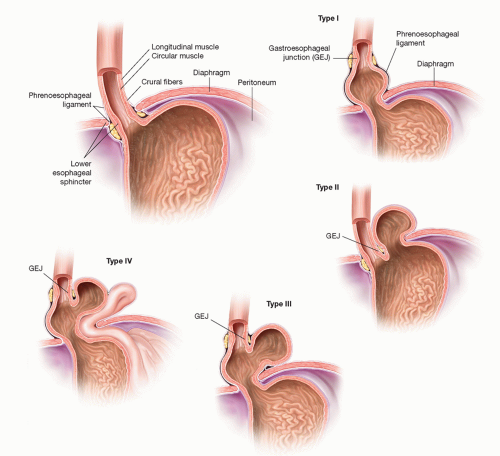

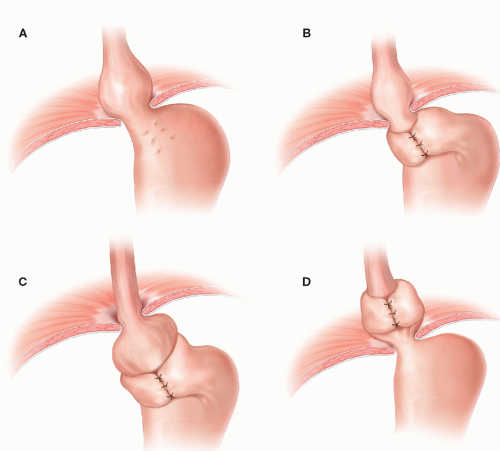

Of the four types of hiatal hernias known today, 95% of incidence resides with the type I or sliding hiatal hernia, which typically can be managed medically with gastric acid suppression. The remaining three types are lumped as “paraesophageal hernias.” These include the true PEH (type II), combined sliding and paraesophageal (type III), and extragastric (type IV) (FIG 1). With the advent of modern antireflux surgery, failed fundoplication overlaps with this classification (FIG 2). Furthermore, disruption of the esophageal hiatus for other disease processes, such as esophagectomy, potentiates the PEH, especially type IV.

This chapter, in concert with other procedures such as fundoplication and esophageal lengthening (Collis gastroplasty), will deal with the surgical management of PEH types II to IV, which anatomically may also encompass redo fundoplication. Principles of repair include definition of anatomy and symptoms, safe reduction of abdominal organs back to the peritoneal cavity, excision of the hernia sac, closure of crura (with or without mesh repair), evaluation of intraabdominal esophageal length, and an antireflux procedure.3,4

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Necessity for PEH repair lies with the patient symptomatology, medical status, and chance of obstruction or strangulation. PEHs can encompass symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), which includes typical symptoms of heartburn, acid reflux, and dyspepsia. In contrast, atypical GERD symptoms manifest as laryngeal and pulmonary complaints of noncardiac chest pain, dyspnea, poor dentition, sinusitis, asthma, chronic cough, pneumonia, and halitosis. PEH-specific complications include gastric volvulus, incarceration, gastric outlet obstruction, and higher mortality when performed emergently. Early studies on mortality in the 1960s demonstrated mortality rates over 50% for PEHs with associated gastric volvulus, although more recent analysis suggests that number to be overestimated and is actually more likely to be under 20% for such patients in duress from PEH.5,6 For all PEH patients, overall mortality is under 1% and can safely be performed with a laparoscopic approach even in the face of obstruction, gangrene, and so forth.7

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Preoperative diagnostic studies help dictate the range of elective, urgent, and emergent nature of a symptomatic patient with a PEH. In those patients who are in extremis, the minimum workup needed for urgent or emergent PEH repair is radiographic evidence of incarceration, perforation, obstruction, or failed antireflux surgery. However, the majority of patients present in an elective manner, and we therefore advocate for a complete workup to assist preoperative planning of the symptomatic patient with PEH by the addition of manometry, pH testing, and endoscopy to rule out pseudoobstruction or esophageal motility disorders.

Chest x-ray: At presentation, whether to an emergency department or a primary care physician’s office, the chest x-ray gives quick and cost-effective information to the severity of the PEH. Mediastinal gas bubble can be seen on plain film radiography as well as the presence of pneumoperitoneum or pneumomediastinum.

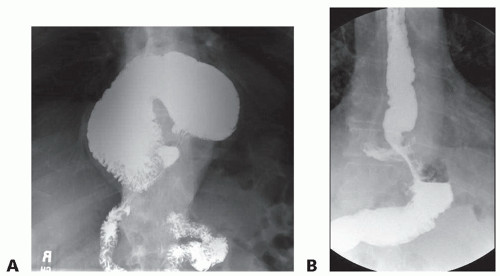

Esophagram: The supine and upright plain film esophagram demonstrates static anatomy and can often locate the gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) in relation to the diaphragm as well as deduce the presence of reflux on delayed films. Mucosal abnormalities can be seen with this modality as well (FIG 3A,B).

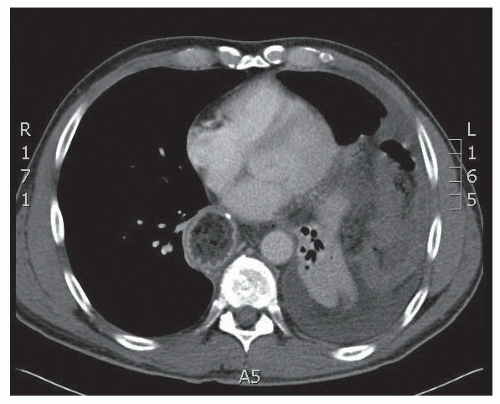

Computed tomography (CT): Indications for obtaining CT scans include the emergent presentation, inconclusive but worrisome findings on two-dimensional radiography, and PEH type IV (FIG 4). CT aids the preoperative planning by alerting the surgeon to the extent of skin preparation and positioning for operative repair but is not necessary.

Upper endoscopy: All preoperative patients should undergo upper endoscopy if possible. By visualization of the esophageal and gastric lumen, neoplasm, Barrett’s esophagus, and esophagitis can be biopsied, and, in case esophagectomy is warranted, provide histologic diagnosis. Furthermore, anatomic landmarks can be seen such as the distance between the hiatus and the GEJ as well as the size of the hiatal hernia.

Manometry: Several studies of benign esophageal disorders confirm the use of preoperative manometry.3,8 Distal esophageal pressures greater than 30 mmHg indicate favorable outcome of response to fundoplication, which, according to some surgeons, is a threshold for performing a complete versus partial wrap for the antireflux component of the PEH repair. Manometry also rules out primary esophageal dysmotility including achalasia, diffuse esophageal spasm, nutcracker esophagus, hypertensive lower esophageal sphincter (LES), and ineffective esophageal motility. We do not advocate performing a complete fundoplication for patients with esophageal dysmotility or low distal esophageal pressures.

pH study: Although the previous modalities of the PEH workup provide a robust description of the PEH patient, pH studies provide data for the decision in failed antireflux

surgery to dissect and redo a previous fundoplication. In the setting of a negative pH study (by way of DeMeester score <15),9 a “herniated” fundoplication may indeed be intact, thus saving the risk of tedious and unnecessary redo fundoplication as a component of the PEH repair.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Preoperative Planning

All studies, including esophagram, esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD), manometry, and pH testing should be readily available and reviewed prior to and at the time of surgery. The esophagram should be displayed on a spare or dedicated monitor in the operating theater and EGD images be loaded as well for intraoperative reference.

Attention to fine detail of the manometric report may avoid an unnecessary and detrimental 360-degree fundoplication, as a complete wrap may worsen symptoms in the light of the following findings8:

Severe esophageal dysmotility

Very low residual postrelaxation LES pressures less than 30 mmHg during wet swallow

Positioning

An operating table capable of steep reverse Trendelenburg position is required. Arms are tucked at the patient’s sides but can be out 90 degrees and secured. Footboards on a split-leg table are mandatory, and a preprocedural reverse Trendelenburg test is used for safety confirmation of positioning (FIG 5A).

Assume extensive mediastinal dissection will be warranted, and therefore, pleural compromise is a frequent occurrence. The sterile skin preparation must be wide enough on either flank in case tube thoracostomies are necessary from resultant pneumothorax. However, a red rubber catheter between 10 and 14 Fr may be placed in a witnessed pleural defect intraabdominally, spanning the diaphragm to the hemithorax in question. This reduces the resultant pneumothorax and peak ventilatory pressures with the aid of lowering insufflation pressures as well as anesthesia-assisted ventilatory Valsalva.

After Veress needle insufflation in either the supraumbilical or the left upper quadrant, trocar placement ensues. Five trocars are used for the laparoscopic PEH repair (FIG 5B). After the liver retractor and ports are placed, the patient is positioned into steep reverse Trendelenburg and the dissection begins.

Instrumentation

As aforementioned, there can be up to a 20% enterotomy rate during PEH repair, especially during redo operations. Therefore, extraordinary care is tantamount to establishing safe dissection planes, especially near the esophagus. Ultrasonic shears are the mainstay of dissection (Harmonic Ace curved shears, Ethicon, Somerville, NJ), whereas when operating extremely close to organs, we advocate switching to laparoscopic scissors as well as blunt dissection to avoid thermal injury.

FIG 4 • CT of massive PEH type IV in which the entire transverse colon has herniated into the left hemithorax. |

FIG 5 • Patient positioning (A) and trocar placement (B). After pneumoperitoneum is established, lines are drawn at the inferior edge of the costal margin diagonally up to an imaginary point above the xiphoid as a zero point for trocar placement. Five trocars are used for the laparoscopic PEH repair. (1) An 11-mm supraumbilical camera port, offset just to the left of the midline and 15 cm inferiorly. (2) A 12-mm left upper quadrant port, measured 12 cm along the parallel line to the left costal margin, for the surgeon’s right hand. This port is placed 1 to 2 cm inferiorly to the 12-cm mark. (3) A 5-mm right upper quadrant trocar, measured 7 to 10 cm from the supraxiphoid point and 1 to 2 cm inferiorly, for the surgeon’s left hand. This can be placed to the right of the falciform and then through the falciform. (4) An assistant’s 5-mm left flank trocar is placed about a palm’s width inferiorly and laterally from the 12-mm trocar. (5) Finally, a 5-mm port is placed and removed in the subxiphoid region for the Nathanson liver retractor. Similarly, a port can be placed at the right flank, symmetrically opposite from the assistant’s port for a linear liver retractor, as supplies may vary per operating theater.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|