Chapter 12

Palliative care in respiratory disease in low-resource settings

Talant M. Sooronbaev

Respiratory Medicine, Intensive Care and Sleep Medicine Department of NCCIM, Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan.

Correspondence: Talant M. Sooronbaev, Respiratory Medicine, Intensive Care and Sleep Medicine Department of NCCIM, 3 Togolok Moldo str, 720040, Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan. E-mail: sooronbaev@yahoo.com

Palliative care for respiratory diseases is a separate and serious problem for low-income countries. Many patients with advanced COPD and other chronic lung diseases who have reached the terminal stage often have disabling symptoms, such as breathlessness, cough, anxiety, depression, pain and fatigue. These patients need to be able to access health professionals with skills in palliative care in order to ensure optimal symptom control. In turn, these patients depend on the adoption of palliative care policies at local and national levels to ensure such access. These networks are, generally, far better developed in high-income countries than in low- and middle-income countries. That is why it is important to develop palliative care in low- and middle-income countries for patients with advanced, progressive respiratory diseases.

There are significant social and healthcare differences between high-, middle- and low-income countries. Many of the underlying causes of these differences are rooted in the long history of development of such nations, and include social, cultural and economic variables, historical and political elements, international relations, and geographic factors. According to the United Nations, a developing country is one with a relatively low standard of living, an undeveloped industrial base and a moderate-to-low Human Development Index. This index is a comparative measure of poverty, literacy, education, life expectancy and other factors that has been reported for countries worldwide [1].

CRDs are currently ranked fifth as a cause of disability [2]. CRDs are the third most frequent cause of mortality globally and are becoming more important in planning health services [3]. Most deaths among patients with CRD occur in patients with COPD. Thus, it has a high prevalence in low-resource settings [4]. According to the European Lung White Book [4], it should also be noted that the mortality rate of all respiratory diseases in low-resource settings occupies a leading position among the European countries and amounts to 143.9 deaths per 100 000 people in Kyrgyzstan. Unfortunately, to date, there are no data for the prevalence or mortality from CRDs in low- and middle-income countries.

According to World Health Organization (WHO) estimates, every year, about 20 million people around the world need palliative care at the EOL [5]. 80% of these people currently live in low- and middle-income countries, about two-thirds are over the age of 60 years and it is estimated that about 6% are children. Most adult patients in need of palliative care die from cardiovascular disease (38.5%), cancer (34%), CRD (10.3%), HIV/AIDS (5.7%) and diabetes (4.6%) [5, 6].

Many patients with advanced COPD and other chronic lung diseases who have reached the terminal stage often have disabling symptoms: breathlessness, cough, anxiety, depression, pain and fatigue. Such patients need to be able to access health professionals with skills in palliative care in order to ensure optimal symptom control. In turn, these people depend on the adoption of palliative care policies at local and national levels to ensure such access. These networks are, generally, far better developed in high-income countries than in low- and middle-income countries. That is why it is important to develop palliative care in low- and middle-income countries for people with advanced, progressive respiratory diseases.

Key definitions and concepts

Definitions of terms used in the field of palliative care are discussed in more detail in the first chapter of this Monograph, but are summarised here to provide context for this discussion [7]. Palliative care is an approach that seeks to optimise the quality of life of patients and their families who face the problem of life-limiting illnesses, to optimise a person’s continued independence for as long as possible, and to reduce suffering by early identification and accurate assessment of the whole person including their clinical care [8]. Palliative care is an important part of public healthcare. It also has goals related to preserving and improving human dignity, and actively identifying the unmet needs of patients and their families throughout the course of the life-limiting illness and, for families and friends, during bereavement [8].

Chronic, progressive diseases are accompanied by various symptoms and various levels of functional impairment. Chronic diseases often occur in combination with other chronic conditions, especially as people age, all of which may impact on a person’s quality of life. Despite the different clinical causes of advanced, life-limiting illnesses, many people experience a similar pattern of symptoms late in life. The intensity of these symptoms and the functional impairment that they cause can vary from person to person and from life-limiting illness to life-limiting illness.

Palliative care should be delivered when a patient needs such care and before the symptoms become uncontrolled. It should not be delivered exclusively by specialised medical teams, palliative care services or hospices [9]. Such care needs to be available from a range of health and clinical services, with specialist services being involved when symptom management becomes more difficult. Specialist palliative care is intensive support for patients or their families with the most complex needs.

Low-income countries

Palliative care is a separate and serious problem for low-income countries. The lack of widespread access to palliative care in low-resource settings is generated by a number of factors, the main one of which is the overall lack of access to adequate health services. There is also sometimes a traditional cultural taboo in sharing patients’ diagnosis and prognosis with them in the setting of a life-limiting illness.

For the successful development of palliative care in low-resource settings, it is necessary to create policies and strategies to create and expand the scope of services, train health personnel, and redistribute financial resources so as to meet the increasing demand as the health of whole populations improves. Initially, this will require a careful analysis of existing policies that can facilitate palliative care, and evaluate the gaps between ideal policies and those currently in place. This gap can then be addressed through policy development.

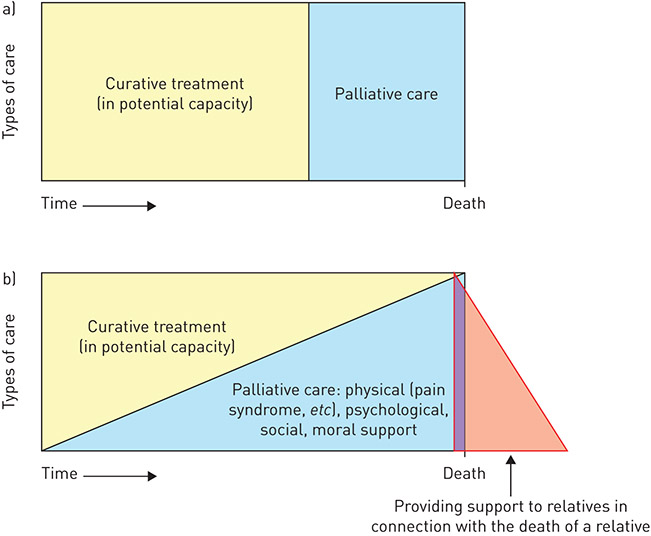

Since 1987, palliative care has been recognised as branch of medicine in its own right. In 1990, for the first time, the WHO defined palliative care with an emphasis on how this approach can be introduced in low-, medium- and high-resource countries. Two concepts of palliative care developed by WHO are presented in figure 1 [10].

Palliative care: 1) respects human life and accepts human mortality; 2) respects the dignity of the patient and their independence, and prioritises their needs; 3) is delivered to all patients suffering from an advanced, progressive disease, regardless of their age; 4) is focused on optimal control and reduction of symptoms, including pain, breathlessness and fatigue; and 5) includes diagnostic measures necessary for the most accurate assessment of the nature of clinical complications causing the patient’s symptoms, adequate treatment of underlying causes when this is appropriate, and optimising the patient’s quality of life.

Palliative care offers: 1) a system of care that supports the sick person, helping them to ensure the best possible quality of life until the death; and 2) support for the patient’s family and friends who provide the majority of care, both during the patient’s life and after their death in bereavement.

In low-resource settings, there is a lack of accurate information about where and how people are dying. At a more detailed level, there is almost no information on the symptom burden of people with life-limiting illnesses. A life-limiting illness causes more than physical symptoms: it can cause emotional, spiritual and social problems for patients and their families. The terminal stages of chronic, progressive diseases (cardiovascular diseases, COPD, diabetes, cancer, HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria) cause patients’ suffering, accompanied by a range of symptoms. In this regard, it is important to understand and implement the basic principles of palliative care, based on simple, available evidence-based approaches (figure 2). In this construct of a framework for quality palliative care, none of the spheres will be effective without interaction with the other two. This requires close and effective interdisciplinary cooperation.