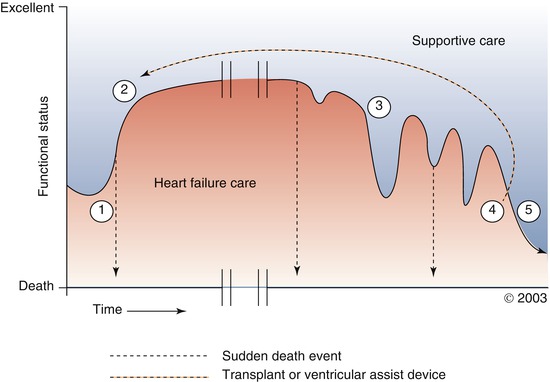

Fig. 3.1

Traditional model for the integration of palliative care and hospice in a terminal illness. Note that this paradigm may be more applicable to cancer patients than patients with advanced cardiovascular disease, and may contribute to the late initiation of discussions surrounding end-of-life care (ellipse) (Adapted from Goldstein [9]. Used with permission)

Estimation of Prognosis

Progression of disease in advanced HF is characterized by acute and severe exacerbations, requiring aggressive medical management. Treatment often provides rapid and durable improvement in symptoms and functional status, but advanced HF patients remain susceptible to rapid decompensation and sudden death. Several risk-profiling scores have been developed to improve physician estimates of prognosis; even so, it remains difficult to predict the disease trajectory for many patients with advanced HF [10–13]. The Seattle Heart Failure Model uses 24 variables to predict 1–3- year survival among patients aged 85 or younger, although it may overestimate survival, particularly among the elderly [13, 14]. Simpler models using fewer variables also may be helpful [15]. Seminal events, such as re-hospitalizations, may provide additional predictors of mortality; median survival after the fourth hospitalization is 1 year or less [16]. Adding to the complexity, many patients with advanced HF have multiple other comorbidities [17]. Under these circumstances, determining prognosis can be difficult not only for cardiologists but also for palliative care and hospice practitioners who may be accustomed to the more predictable clinical decline at EOL seen in patients with solid organ tumors [18]. Prognostic uncertainty in advanced HF is a problem that is unlikely to be resolved; physicians may miss opportunities to explore patient wishes regarding EOL care unless discussions of prognosis and the uncertainty surrounding it begin early in the course of therapy.

Communication Around Prognosis

Physicians may feel reluctant to address the possibility of dying with their patients, but patients and their caregivers frequently find such information helpful [19]. Because of the uncertainty intrinsic to advanced HF prognosis, discussions that include acknowledgement of HF as a life-limiting illness should begin early in the course of therapy. Communication about prognosis and preferences regarding EOL care should be viewed as an ongoing process. Initial discussions may be quite brief, but as the disease progresses, more in-depth conversations will become necessary. To communicate effectively in these difficult situations, it is important to assess what the patient knows and wants to know about the disease and its prognosis. Cognitive impairment is common among HF patients [20]; if appropriate, clinicians should offer to include caregivers in the discussion [21]. One simple but effective model for “bad news” conversations is “ask-tell-ask” [22]. The clinician starts by asking about the patient’s understanding, then tells information, and finally asks for feedback from the patient. Eliciting questions and establishing a common understanding require careful attention not just to the words spoken but also to the emotions displayed. The extent of discussion will depend on the readiness of the patient and family to hear and accept what the clinician is saying. In the event that a patient is reluctant to address EOL issues, the clinician may conclude the discussion by asking permission to raise the topic again at a future visit.

Timing of Palliative Care and Hospice Referrals

Palliative care referral is appropriate if a HF patient could benefit from specific attention to symptom management and help with advanced care planning, regardless of whether the patient is receiving aggressive medical management. In particular, palliative care consultation may benefit patients who are undergoing evaluation for advanced HF therapies, such as continuous inotrope infusions, ventricular assist devices (VAD), and heart transplantation [23]. Other prompts for palliative care consultations may include worsening HF requiring repeated hospitalizations, and patient or family request for more information. Not all palliative care, however, needs to be provided by specialists; in some hospitals, checklists are used to identify patients in need of “primary” or basic palliative care interventions versus those in need of more complex palliative care services [24]. Integration of palliative care concepts into HF clinics may allow for gentler transitions when patients with advanced heart disease approach EOL.

Although HF patients comprise only a small portion of hospice beneficiaries, use of hospice services has been increasing both in general and in the HF population in recent years [25]. For any given disease, the Medicare hospice benefit requires a physician to certify that a patient’s life expectancy is 6 months or less if the disease were to run its natural course. In the case of HF, the Medicare guidelines rely heavily on the New York Heart Association (NYHA) symptom class and associated co-morbidities. One obstacle to timely hospice referral for HF patients is that even using the best risk profiling scores, it is difficult to give an estimate of prognosis that is precise enough to fit in the 6-month window. In addition, hospice agencies are not uniform in their coverage of advanced HF treatments, particularly more expensive therapies like home inotrope infusions and VAD therapy. It is important that the clinician, patient, and family be aware of potential limitations prior to initiation of advanced HF therapies, as these therapies may dictate where the patient can receive EOL care. Early integration of discussions about patient preferences for EOL care may help when it is time to transition to hospice care.

Advanced Care Planning

An advance directive (AD) is a legal document that provides guidance about a person’s wishes for medical care. ADs frequently also designate a “durable power of attorney for healthcare” or surrogate decision-maker. These documents go into effect only if a person becomes unable to speak for himself. A recent study found that AD use is low among HF patients, but that patients who had completed an AD were less likely to be transferred to an intensive care unit (ICU) or to receive mechanical ventilation [26]. In addition, good patient-physician communication around advanced care planning improves patient satisfaction with their medical care [27]. Palliative care consultation has been shown to increase preparedness planning and use of ADs amongst patients being evaluated for VAD placement [28]. The idea that one should “hope for the best and prepare for the worst” will be recognized by most people. This concept may be used to communicate the clinician’s desire to support the patient in their quest for life prolonging therapy in the face of a life limiting illness [29]. Focusing conversations about patient preferences for EOL care on “big picture goals” and values, instead of specific treatment decisions, may prove helpful in guiding future care [21].

Symptom Management

Patients with end-stage cardiovascular disease suffer from a significant burden of symptoms, due to both the pathophysiology of HF and to comorbidities common in HF patients, such as arthritis and sleep-disordered breathing. Although comorbid conditions must be addressed, the cornerstone of symptom management in advanced HF is optimization of the medical treatment itself. Common symptoms reported by patients with advanced HF include dyspnea, pain, fatigue, anorexia, depression, and anxiety [30].

Dyspnea

The first line of treatment for dyspnea in advanced HF is management of fluid status and systolic dysfunction with diuretics, vasodilators, intravenous inotropes, fluid restriction, and reduced sodium diet. As HF progresses, the ability to manage dyspnea by optimizing volume status may be hampered by hypotension and renal insufficiency. Although the mechanisms are not fully understood, low-dose opioids may provide relief in dyspnea refractory to diuresis [31]. Oxygen supplementation is frequently used to treat dyspnea, particularly in hypoxemic patients. Even patients without significant hypoxemia may derive benefit; however, it is not clear whether this is due to the oxygen itself or to the sensation of air flow [32]. Benzodiazepines also may be used as a second-line therapy, particularly for anxiety associated with dyspnea at EOL [33].

Pain

Pain is a common and debilitating symptom in patients with HF [34]. Although the causes are not completely understood, pain may result from the underlying pathophysiology of HF itself or it may be associated with frequently occurring comorbidities, including degenerative arthritis, anxiety, and depression [34, 35]. General principles of pain management can be applied to the treatment of pain in HF patients; however, special attention must be paid to drug selection and dosing, and therapeutic effectiveness must be frequently reassessed [36]. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents are not recommended in HF patients due to their tendency to cause sodium and fluid retention; worsen kidney function; increase the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding; and potentiate adverse effects of important HF treatments, such as diuretics, angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors, and angiotensin II receptor blockers [37].

Fatigue

Many end stage HF patients struggle with fatigue, which may be associated with low cardiac output, depression, obstructive sleep apnea, and anemia. Screening and treatment for underlying causes of fatigue can improve patients’ quality of life. Treatment of sleep apnea with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) has been shown to improve heart function, mental alertness and fatigue in patients with HF [37]. Decreased cardiac output may be treated with intravenous inotropes if it is consistent with the patient’s goals of care. When appropriate, treatment of anemia with erythropoietin can improve exercise tolerance and overall quality of life in patients with advanced HF [38]. In addition, graded exercise programs, low-dose opioids, and caffeine have shown benefit in treating fatigue associated with exertion [39–41].

Depression and Anxiety

Patients with advanced HF face uncertainty about the future and loss of independence. Depression is common, but may be difficult to recognize in advanced HF, as many of the symptoms of depression are also symptoms of HF [42]. Supportive counseling may be beneficial, as may some complementary and alternative medicine interventions, such as mindfulness-based stress reduction [43]. For those patients who require pharmacologic treatment, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), tricyclic antidepressants, benzodiazepines, and psychostimulants, such as methylphenidate, have all shown some benefit in the treatment of depression, particularly when used in conjunction with counseling [44]. Benzodiazepines should be used with caution in the elderly due to potential adverse effects of sedation and confusion. Psychostimulants may be a better option in patients for whom a rapid response is important, although patients may experience worsening anxiety or agitation. All HF patients started on antidepressant medication should be monitored for mental status changes, prolongation of the QT interval, orthostatic hypotension, and hyponatremia.

Anorexia and Cachexia

Weight loss and anorexia in advanced HF patients are thought to be related to neuro-hormonal effects of HF itself. Little data exist about the effectiveness of pharmacological treatment of anorexia and cachexia, therefore potentially treatable underlying causes of anorexia must be addressed, including hypothyroidism, depression, intestinal edema, and uncontrolled pain [45]. Appetite stimulants may be helpful in cancer-related anorexia, but can cause side effects that may outweigh the benefits in HF patients. Discussions about the reasons for anorexia and weight loss in advanced HF may allow patients and families to focus less on the quantity of food consumed and more on the quality of the experience. Encouraging smaller servings of favorite foods and liberalizing dietary restrictions when appropriate can benefit the patient with end stage heart disease.

Technological Advances and End-of-Life Care

Over the past several decades, there has been tremendous progress in the development of highly technological treatment modalities for advanced HF. Cardiac transplantation, the “gold standard” for the treatment of advanced HF, is limited by the number of donor hearts, but the number of patients receiving some form of device therapy has been rising steadily for the past 10 years. Although not all people with advanced HF receive these treatments, they deserve special mention because they can complicate EOL care Fig. 3.2.

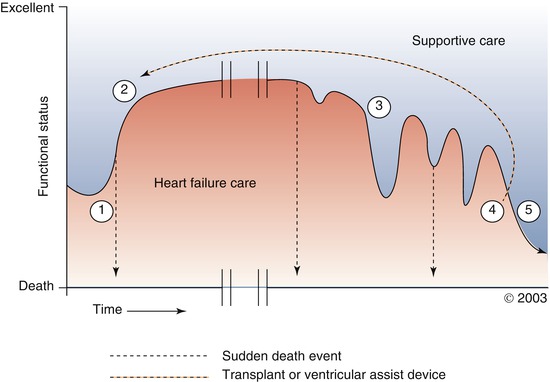

Fig. 3.2

Schematic course of Stage C and D heart failure. Sudden death may occur at any point along the course of illness. (1) Initial symptoms of heart failure (HF) develop and HF treatment is initiated. (2) Plateaus of variable length may be reached with initial medical management or after mechanical circulatory support (MCS) or heart transplant. (3) Functional status declines with variable slope, with intermittent exacerbations of HF that respond to rescue efforts. (4) Stage D HF, with refractory symptoms and limited function. Note that heart transplantation or MCS may result in a return to an earlier plateau on the disease trajectory. (5) End of life (Adapted with permission from Goodlin et al. [17])

Heart Transplantation

Despite improvements in medical and device therapy for HF, heart transplantation remains the best option for advanced HF patients who qualify for it. The primary limitation of heart transplantation is the scarcity of donor hearts. The annual number of heart transplants in the US is around 2,200, and there has been little change in this figure since 1998 [46]. Perioperative mortality rates have dropped since the 1980s; patients who survive their first year have a 63 % chance of surviving to 10 years [47]. In addition to the physical symptoms of advanced HF, patients awaiting heart transplantation may encounter emotional or existential distress related to the uncertainty of knowing whether they will receive a donor heart. Most patients wait for weeks to months, but a substantial proportion (30–37 %) may wait for over a year [48]. In the past, concurrent transplant evaluation and palliative care consultation may have been viewed as contradictory, but more recent research indicates that this patient population may benefit from systematic integration of palliative care into their treatment plans [49].

Mechanical Circulatory Support

Ventricular assist devices (VADs) have been shown to decrease morbidity and mortality among patients with HF refractory to medical management [50]. As a result, VADs have become an important HF treatment modality, both as a bridge to cardiac transplantation and as “destination therapy.” From 2006 to 2010, the number of VADs implanted in the US increased from 206 to 1,451 [51]. Mean survival for advanced HF patients increases from 6 months with medical therapy alone to 2 years with the addition of continuous-flow VADs [52–54]. This technology is expensive – the cost is almost six times higher than the cost of medical management; however, continuous-flow VAD patients may experience dramatic improvements in quality of life compared to medically managed patients [55].

Despite advancements in VAD technology, adverse events may occur, leading to increased morbidity, hospitalization, and death. The most common causes of death among VAD patients include stroke, worsening HF or VAD failure, sepsis, multi-organ failure, and infection [56–60]. EOL care for patients with VADs may be complicated by the need to obtain care at tertiary care centers as smaller hospitals lack experience with the devices. In addition, many hospice organizations may be unable to support the care of VAD patients due to lack of familiarity and high cost. As the VAD patient population grows, questions of how to handle death and dying in these patients and the need for formalized support for patients, caregivers, and staff will become more prominent.

Pacemakers and Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillators

Pacemakers have improved the quality and length of life for patients with bradyarrhythmias for decades [61]. More recently, implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs) have demonstrated substantial survival benefits for patients at risk for sudden cardiac death [62]. Cardiac resychronization therapy may also improve symptoms and survival [63]. Since a major benefit of cardiac pacing therapies is symptom relief, the question of how to manage these devices at EOL is not usually problematic. The majority of ICDs, on the other hand, are implanted not for symptom relief, but to reduce the risk of sudden death. Up to 20 % of patients with ICDs can experience painful shocks in the last few weeks of their lives, and these shocks can impair patients’ quality of life and cause distress amongst their caregivers [64]. Patients and caregivers may also have misconceptions about what ICDs do, and what to expect if they are turned off [65]. Guidelines and consensus statements issued by the major cardiology societies strongly encourage physicians and patients to discuss the option of ICD deactivation at the EOL prior to implantation, and it is recommended that organizations caring for patients with ICDs have a formal policy regarding ICD deactivation [66]. Unfortunately many hospice programs do not have such policies – a 2010 survey of 900 hospices across the US revealed that patients in hospices that had established policies regarding ICD deactivation were twice as likely to have their device turned off, but that only 10 % of hospices had such policies [67]. Although deactivating an ICD may shorten survival time, physicians should emphasize that it will not result in immediate death and that the process of deactivation is not painful. If a patient decides that deactivation is the right choice, the ICD function may be deactivated by reprogramming the device, which can occur at home, in the clinic, or in the hospital. Organizations that care for patients with ICDs should have protocols in place for patients who are actively dying but have not deactivated their ICD. The ICD function of most devices can be disabled by placing a magnet on top of the device generator; as long as the magnet remains in place, the ICD will not sense arrhythmias and will not deliver shocks (pacemaker functions will not be disabled by the magnet, although they may revert to the default settings).

IV Intravenous Inotropes

Continuous infusions of inotropes have not demonstrated a survival benefit for advanced HF patients; however, in some cases these medications may improve symptoms. The role of continuous IV inotropes in the EOL care of advanced HF patients has not been well-studied. Advanced HF patients who do not qualify for transplant or VAD treatment and are started on palliative inotrope infusions have very high mortality rates and may have a shortened lifespan as a result of inotropic therapy [68]. There is no easy way to know whether a person facing EOL will choose quality of life or quantity of life. Talking to patients about options before they reach the terminal stages of disease is still the best way to understand treatment preferences [69].

Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Do-Not-Resuscitate Orders

Hospitalized patients with advanced HF are far less likely to have Do-Not-Resuscitate (DNR) orders in place than patients with advanced cancer; they are also far more likely to receive life-sustaining treatments during their final hospitalization [70, 71]. Some of the reluctance on the part of both physicians and patients to discuss or institute DNR orders may be a perception that patients with DNR orders get substandard care. Indeed, there is some evidence that advanced HF patients who have DNR orders are less likely to meet quality of care performance measures [72]. Providers should be explicit that DNR orders apply only to resuscitation, and that optimal management of HF and its symptoms is the goal for all patients, regardless of resuscitation preferences. Inquiring about “code status” is not the best way to introduce a discussion of EOL issues, but this is commonly how the subject is broached in acute care hospitals [73]. A more fruitful way of framing the question might be to focus not on what people want when they die (or almost die), but how they want to live up to that point. For some patients with advanced HF, the decision to request DNR status may represent a willingness to trade length of life for quality of life [74]. Considered discussion of the patient’s goals and of how various treatment options will promote the best quality of life should begin in the outpatient setting and continue in the inpatient setting. If CPR will help the patient achieve his or her goals, it should be offered for consideration; if not, it should be presented as “inadvisable” [75].

Care of Adults with Congenital Heart Disease

Although congenital heart disease (CHD) affects relatively few people, it is one of the most common birth defects. In the past, infant mortality from CHD was quite high, but advances in cardiology and cardiac surgery have changed the demographics of this disease; over 90 % of children born with CHD now survive to adulthood [76]. Further study is needed to develop guidelines for EOL care of this patient population, but strategies of care used for other patient populations with early onset disease, such as cystic fibrosis and childhood cancers, may prove useful [77]. Because symptoms of worsening HF may not manifest until late in the disease course, these patients require an early and proactive approach to discussions about life-prolonging treatment options and wishes regarding EOL care [78].

Hospice Care and Advanced Heart Failure Treatments

In part because of difficulties with prognostication, use of hospice care remains low among patients with advanced HF relative to patients with cancer [79]. In addition, clinicians and advanced HF patients may have misconceptions about hospice, believing that it is only for people who are actively dying and not for people who maintain some capacity to function. Patients with HF are much more likely than patients with cancer to be referred to hospice during an acute hospitalization, and they are also much more likely to return to the hospital despite hospice enrollment [80]. Hospices are reimbursed on a per diem basis – currently most US hospices receive about $150/day to cover all of a patient’s care, including personnel, medications, and durable medical equipment [81]. As a result, hospices generally provide oral medications only; many are unable to support more high-technology treatments like continuous inotrope infusions, bi-level positive airway pressure (BiPAP), or VADs. In addition, some hospices may not be given, or do not ask for, necessary clinical data when admitting HF patients [82]. Dealing with the complex EOL care of patients with advanced HF will require specialists in cardiology and in hospice and palliative care to refine the current practice. Cardiology specialists should continue to be involved when advanced HF patients are referred to hospice. Educating hospice and palliative care practitioners about advanced HF remains a critical need, and will only be improved by a collaborative approach.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree