P-Q

Parainfluenza

Parainfluenza refers to any of a group of respiratory illnesses caused by paramyxoviruses, a subgroup of the myxoviruses. Affecting both the upper and lower respiratory tracts, these self-limiting diseases resemble influenza but are milder and seldom fatal. They primarily affect young children.

CAUSES AND INCIDENCE

Parainfluenza is transmitted by direct contact or by inhalation of contaminated airborne droplets. Paramyxoviruses occur in four forms—Para 1 to 4—that are linked to several diseases: croup (Para 1, 2, 3); acute febrile respiratory illnesses (1, 2, 3); the common cold (1, 3, 4); pharyngitis (1, 3, 4); bronchitis (1, 3); and bronchopneumonia (1, 3). Para 3 ranks second to respiratory syncytial viruses as the most common cause of lower respiratory tract infections in children. Para 4 rarely causes symptomatic infections in humans.

Parainfluenza is rare among adults but widespread among children, especially males. By age 8, most children demonstrate antibodies to Para 1 and Para 3. Most adults have antibodies to all four types as a result of childhood infections and subsequent multiple exposures. Reinfection is usually less severe and affects only the upper respiratory tract. Incidence rises in the winter and spring.

Upon exposure, the major site of virus binding and subsequent infection is the respiratory epithelium. The virus causes airway inflammation, necrosis and sloughing of respiratory epithelium, edema, excessive mucus production, and interstitial infiltration of the lung. Edema of the mucus layer causes swelling (occurring in the vocal cords, larynx, trachea, and bronchi), leading to obstruction of airway inflow and stridor.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

After a short incubation period (usually 3 to 6 days), signs and symptoms emerge that are similar to those of other respiratory diseases, including:

• chills

• muscle pain

• nasal discharge

• reddened throat (with little or no exudate)

• sudden fever.

COMPLICATIONS

• Croup

• Laryngotracheobronchitis

• Bronchiolitis

• Pneumonia

DIAGNOSIS

Parainfluenza infections are usually clinically indistinguishable from similar viral infections. A swab of nasal secretions allows for rapid viral testing. Although isolation of the virus and serum antibody titers can differentiate parainfluenza from other respiratory illnesses, it’s rarely performed.

TREATMENT

Depending on the severity of signs and symptoms, treatment can range from no treatment to bed rest and use of antipyretics, analgesics, and antitussives. Complications, such as croup and pneumonia, require appropriate treatment. Corticosteroids and nebulization help control respiratory symptoms and reduce airway edema.

Drugs

• Corticosteroids, such as dexamethasone (Decadron, Solurex, Dexasone), prednisone (Deltasone, Orasone, Meticorten, Sterapred), and prednisolone (Delta-Cortef, Articulose-50, Econopred), to reduce airway inflammation; budesonide (Pulmicort Respules, Turbuhaler) given via inhaler for the same purpose

• Sympathomimetics such as epinephrine (AsthmaNefrin, microNefrin, S-2) to reverse upper airway edema

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

• Throughout the illness, monitor respiratory status and temperature, and ensure adequate fluid intake and rest.

• The easiest and most effective way to prevent the spread of infection is to practice good hand washing.

Pharyngitis

The most common throat disorder, pharyngitis is an acute or chronic inflammation of the pharynx. It frequently accompanies the common cold.

CAUSES AND INCIDENCE

Viruses account for 40% to 60% of pharyngitis cases and bacteria cause 5% to 40% of cases, with allergies, trauma, toxins, and neoplasias accounting for the rest. The most common bacterial cause is group A beta-hemolytic streptococci; others include Mycoplasma and Chlamydia.

The peak incidence of bacterial and viral pharyngitis occurs in children ages 4 to 7 years; it’s rare in children younger than 3 years. Non-infectious pharyngitis is widespread among adults who live or work in dusty or very dry environments, use their voices excessively, habitually use tobacco or alcohol, or suffer from chronic sinusitis, persistent coughs, or allergies.

With infectious pharyngitis, bacteria or viruses may directly invade the pharyngeal mucosa, causing inflammation. Other viruses, such as rhinovirus, cause nasal secretions, which in turn irritate the mucosa. Streptococcal infections release extracellular toxins and proteases,

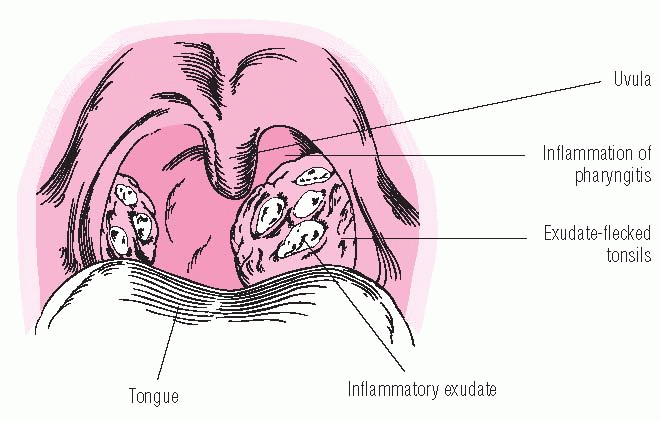

which can cause such complications as rheumatic fever, heart valve damage, and acute glomerulonephritis. (See Acute pharyngitis.)

which can cause such complications as rheumatic fever, heart valve damage, and acute glomerulonephritis. (See Acute pharyngitis.)

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Typically, the patient complains of:

• a sore throat

• slight difficulty swallowing (swallowing saliva hurts more than swallowing food)

• sensation of a lump in the throat

• a constant and aggravating urge to swallow

• headache

• muscle and joint pain (especially in bacterial pharyngitis)

• mild fever

• pharyngeal wall appears fiery red, with swollen,

• exudate-flecked tonsils and lymphoid follicles

• acutely inflamed throat with patches of white and yellow follicles (bacterial pharyngitis)

• strawberry red tongue

• enlarged, tender cervical lymph nodes.

COMPLICATIONS

• Otitis media

• Sinusitis

• Mastoiditis

• Rheumatic fever

• Nephritis

• Glomerulonephritis

• Toxic shock syndrome

• Pneumonia

DIAGNOSIS

• A throat culture can identify any bacterial organisms causing inflammation, but it may not detect other causative organisms.

• Rapid strep tests generally detect group A streptococcal infections, but they miss the fairly common streptococcal groups C and G.

• Computed tomography scanning can identify the location of abscesses.

• A white blood cell (WBC) count is used to determine atypical lymphocytes; an elevated total WBC count is present.

TREATMENT

Treatment for acute viral pharyngitis is usually symptomatic and consists mainly of resting, gargling with warm saline solution, sucking throat lozenges that contain a mild anesthetic, drinking plenty of fluids, and taking analgesics as needed. If the patient can’t swallow fluids, he may need I.V. hydration.

Suspected bacterial pharyngitis requires rigorous treatment with penicillin or another broad-spectrum antibiotic because Streptococcus (the most likely infecting organism) could lead to the development of acute rheumatic fever. Antibiotic therapy should continue for 48 hours until culture results are back. If the culture or a rapid strep test is positive for group A beta-hemolytic streptococci, or if bacterial infection is suspected despite negative culture results, penicillin therapy should continue for 10 days.

Chronic pharyngitis requires the same supportive measures as acute pharyngitis but with greater emphasis on eliminating the underlying cause, such as an allergen. Preventive measures include adequate humidification and avoiding excessive exposure to air conditioning. In addition, the patient should be urged to stop smoking.

Drugs

• Antimicrobials appropriate to the specific causative agent to combat infection

• Corticosteroids, such as dexamethasone (Decadron) or prednisone (Deltasone, Orasone, Sterapred), to reduce airway edema in cases of airway obstruction

• Antifungals, such as nystatin (Mycostatin) or fluconazole (Diflucan), to combat oral thrush

• Antivirals, such as acyclovir (Zovirax), famciclovir (Famvir), ganciclovir (Cytovene, Vitrasert), and foscarnet (Foscavir), for a severe mucocutaneous HSV infection or an immunocompromised patient

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

• Administer analgesics and warm saline gargles, as ordered and as appropriate.

• Encourage the patient to drink plenty of fluids. Scrupulously monitor intake and output, and watch for signs of dehydration.

• Provide meticulous mouth care to prevent dry lips and oral pyoderma, and maintain a restful environment.

• Obtain throat cultures, and administer antibiotics as needed. If the patient has acute bacterial pharyngitis, emphasize the importance of completing the full course of antibiotic therapy. Tell him to call his

practitioner if he experiences any adverse reactions.

practitioner if he experiences any adverse reactions.

• Inform the patient and his family that in the case of positive streptococcal infection, the family should undergo throat cultures regardless of the presence or absence of symptoms. Those with positive cultures require penicillin therapy.

• Teach the patient with chronic pharyngitis steps he can take to minimize environmental sources of throat irritation such as using a humidifier in the bedroom.

• Refer the patient to a self-help group to stop smoking if appropriate.

• Tell the parents of a school-age child with infectious pharyngitis that the child should receive at least 24 hours of therapy before returning to school.

• A patient who has exhibited three or more documented bacterial infections within 6 months may need daily penicillin prophylaxis during the winter months; carriers who live in closed or semiclosed communities may also need treatment.

Pleural effusion and empyema

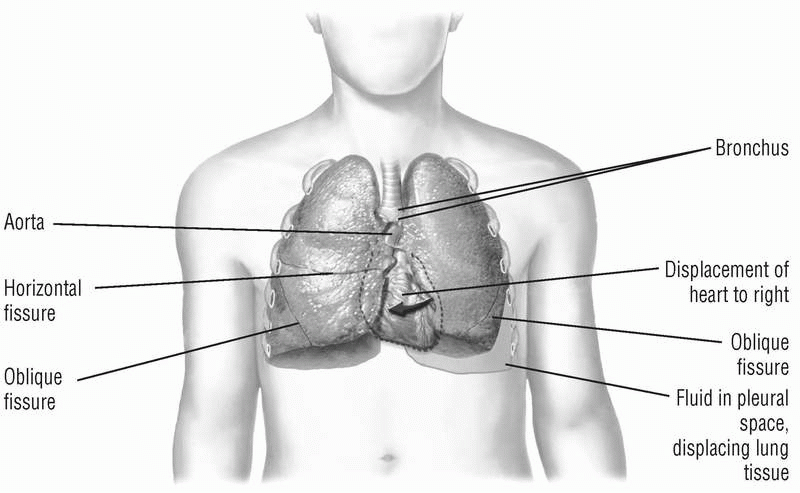

Pleural effusion is an excess of fluid in the pleural space. Normally, this space contains a small amount of extracellular fluid that lubricates the pleural surfaces. Increased production or inadequate removal of this fluid results in pleural effusion. Empyema is the accumulation of pus and necrotic tissue in the pleural space. Blood (hemothorax) and chyle (chylothorax) may also collect in this space.

CAUSES AND INCIDENCE

The balance of osmotic and hydrostatic pressures in parietal pleural capillaries normally results in fluid movement into the pleural space. Balanced pressures in visceral pleural capillaries promote reabsorption of this fluid. Excessive hydrostatic pressure or decreased osmotic pressure can cause excessive amounts of fluid to pass across intact capillaries. The result is a transudative pleural effusion, an ultrafiltrate of plasma containing low concentrations of protein. Such effusions can result from heart failure, hepatic disease with ascites, peritoneal dialysis, hypoalbuminemia, and disorders resulting in overexpanded intravascular volume. (See Lung compression in pleural effusion, page 122.)

Exudative pleural effusions result when capillaries exhibit increased permeability with or without changes in hydrostatic and colloid osmotic pressures, allowing protein-rich fluid to leak into the pleural space. Exudative pleural effusions occur with tuberculosis, subphrenic abscess, pancreatitis, bacterial or fungal pneumonitis or empyema, malignancy, pulmonary embolism with or without infarction, collagen disease (lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis), myxedema, and chest trauma.

Empyema is usually associated with infection in the pleural space.

Such infection may be idiopathic or may be related to pneumonitis, carcinoma, perforation, or esophageal rupture.

Such infection may be idiopathic or may be related to pneumonitis, carcinoma, perforation, or esophageal rupture.

Pleural effusion affects 1.3 million people each year. Morbidity and mortality are directly related to the cause, the stage of disease at the time of onset, and findings in the pleural fluid analysis. Patients with malignant pleural effusion have a poor prognosis, with a life expectancy of 3 to 6 months.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

The patient’s history characteristically shows underlying pulmonary disease. Signs and symptoms include:

• dyspnea (with effusion)

• pleuritic chest pain (with pleurisy)

• general feeling of malaise (with empyema)

• tracheal has deviation

• fever (with empyema)

• decreased tactile fremitus (with a large amount of effusion)

• dullness over the effused area that doesn’t change with respiration.

• diminished or absent breath sounds over the effusion

• a pleural friction rub during both inspiration and expiration

• bronchial breath sounds, sometimes with the patient’s pronunciation of the letter “e” sounding like the letter “a.”

COMPLICATIONS

• Atelectasis

• Infection

• Hypoxemia

DIAGNOSIS

Chest X-rays show radiopaque fluid in dependent regions (usually with fluid accumulation of more than 250 ml). A negative tuberculin skin test helps rule out tuberculosis as a cause. A pleural biopsy can help confirm tuberculosis or cancer if thoracentesis doesn’t provide a definitive diagnosis in exudative pleural effusion.

Analysis of fluid aspirated during thoracocentesis can provide the following information:

• In transudative effusion, fluid usually has a specific gravity less than 1.015 and contains less than 3 g/dl of protein.

• Exudative effusion has a ratio of protein in the fluid to serum of greater than or equal to 0.5, pleural fluid lactate dehydrogenase (LD) of greater than or equal to 200 IU, and a ratio of LD in pleural fluid to LD in serum of greater than or equal to 0.6.

• In empyema, aspirated fluid contains acute inflammatory white blood cells and microorganisms and shows leukocytosis.

• In empyema and rheumatoid arthritis, which can be the cause of an exudative pleural effusion, fluid shows an extremely decreased pleural fluid glucose level.

• Pleural effusion that results from esophageal rupture or pancreatitis usually has fluid amylase levels higher than serum levels.

• Aspirated fluid may also be tested for lupus erythematosus cells, antinuclear antibodies, and neoplastic cells and analyzed for color and consistency; acid-fast bacillus, fungal and bacterial cultures, and triglycerides (in chylothorax).

TREATMENT

Depending on the amount of fluid present, symptomatic pleural effusion may require either thoracentesis to remove fluid or careful monitoring of the patient’s own reabsorption of the fluid. Hemothorax requires drainage to prevent fibrothorax formation.

Pleural effusions associated with lung cancer commonly reaccumulate quickly. If a chest tube is inserted to drain the fluid, a sclerosing agent, such as talc, may be injected through the tube to cause adhesions between the parietal and visceral pleura, thereby obliterating the potential space for fluid to recollect.

Treatment of empyema requires insertion of one or more chest tubes after thoracentesis to allow purulent material to drain, and possibly decortication (surgical removal of the thick coating over the lung) or rib resection to allow open drainage and lung expansion. Empyema also requires parenteral antibiotics. Associated hypoxia requires oxygen administration.

Drugs

• Antimicrobials specific to the type of organism involved to combat the infecting organism

• Diuretics, such as furosemide (Lasix) or spironolactone (Aldactone), as needed to promote diuresis

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

• Explain thoracentesis to the patient. Before the procedure, tell him to expect a stinging sensation from the local anesthetic and a feeling of pressure when the needle is inserted. Instruct him to tell you immediately if he feels uncomfortable or has difficulty breathing during the procedure.

• Reassure the patient during thoracentesis. Remind him to breathe normally and to avoid sudden movements, such as coughing or sighing. Monitor his vital signs, and watch for syncope. If fluid is removed too quickly, the patient may suffer bradycardia, hypotension, pain, pulmonary edema, or even cardiac arrest.

After thoracentesis, watch for respiratory distress and signs of pneumothorax (sudden onset of dyspnea and cyanosis).

• Administer oxygen and, in empyema, antibiotics, as ordered.

• Encourage the patient to perform deep-breathing exercises to promote lung expansion. Use an incentive spirometer to promote deep breathing.

• Provide meticulous chest tube care, and use sterile technique for changing dressings around the tube insertion site in empyema. Ensure tube patency by watching for fluctuations of fluid or air bubbling in the water-seal chamber. Continuous bubbling may indicate an air leak. Record the amount, color, and consistency of any tube drainage.

• If the patient has open drainage through a rib resection or intercostal tube, use hand and dressing precautions. Because weeks of such drainage are usually necessary to obliterate the space, make visiting nurse referrals for the patient who will be discharged with the tube in place.

• If pleural effusion was a complication of pneumonia or influenza, advise prompt medical attention for upper respiratory infections.

Pleurisy

Pleurisy, also known as pleuritis, is an inflammation of the visceral and parietal pleurae that line the inside of the thoracic cage and envelop the lungs.

CAUSES AND INCIDENCE

Pleurisy develops as a complication of pneumonia, tuberculosis, viruses, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, uremia, Dressler’s syndrome, certain cancers, pulmonary infarction, and chest trauma. Pleuritic pain is caused by the inflammation or irritation of sensory nerve endings in the parietal pleura. As the lungs inflate and deflate, the visceral pleura covering the lungs moves against the fixed parietal pleura lining the pleural space, causing pain. This disorder usually begins suddenly. The normal pleural space contains approximately 1 ml of fluid, balancing hydrostatic and oncotic forces (in the visceral and parietal pleural

vessels) and lymphatic drainage. Pleural effusions result when a disruption occurs in this balance.

vessels) and lymphatic drainage. Pleural effusions result when a disruption occurs in this balance.

In the United States, the estimated incidence is 1 million cases per year. Most are caused by heart failure, malignancy, infections, and pulmonary emboli.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Signs and symptoms of pleurisy include:

• sudden, sharp, stabbing pain that worsens on inspiration

• shallow, rapid breathing

• dyspnea

• pleural friction rub—a coarse, creaky sound heard during late inspiration and early expiration—directly over the area of pleural inflammation.

• coarse vibrations over the affected area.

COMPLICATIONS

• Permanent adhesions that can restrict lung expansion

DIAGNOSIS

• Electrocardiography rules out coronary artery disease as the source of the patient’s pain.

• Chest X-rays can identify pneumonia.

• Ultrasonography of the chest and thoracentesis may aid in diagnosis.

TREATMENT

Treatment is directed at the underlying cause; bacterial infections are treated with appropriate antibiotics, tuberculosis requires special treatment, and viral infections may be permitted to run their course. Treatment also includes measures to relieve signs and symptoms, such as anti-inflammatory agents, analgesics, and bed rest. Severe pain may require an intercostal nerve block of two or three intercostal nerves. Pleurisy with pleural effusion calls for thoracentesis as a therapeutic and diagnostic measure.

Drugs

• Antimicrobials specific to the type of organism involved to combat the infecting organism

• Analgesics to relieve pain

• Antitussives to relieve cough

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

• Stress the importance of bed rest, and plan your care to allow the patient as much uninterrupted rest as possible.

• Asses the patient for pain every 3 hours, and administer antitussives and pain medication as ordered, but be careful not to overmedicate. Pain relief allows for maximum chest expansion. If the pain requires an opioid analgesic, warn the patient who’s about to be discharged to avoid overuse because such medication depresses coughing and respiration.

• Encourage the patient to take deep breaths and to cough. To minimize pain, apply firm pressure at the site of the pain while the patient coughs.

• Encourage the use of incentive spirometry every hour and instruct the patient on proper use.

• Place the patient in high Fowler’s position to help lung expansion. Positioning him on the affected side may aid in splinting.

• Assess the patient’s respiratory status at least every 4 hours to detect early signs of compromise. Monitor for such complications as fever, increased dyspnea, and changes in breath sounds.

• Plan your care to allow the patient as much uninterrupted rest as possible.

• Pain can impair the patient’s mobility, so help him perform active and passive range-of-motion exercises to prevent contractures and promote muscle strength.

• If the patient needs thoracentesis, remind him to breathe normally and avoid sudden movements, such as coughing or sighing, during the procedure. Monitor his vital signs, and watch for syncope. Also watch for indications that fluid is being removed too quickly: bradycardia, hypotension, pain, pulmonary edema, and cardiac arrest. Reassure the patient throughout the procedure.

After thoracentesis, watch for respiratory distress and signs of pneumothorax (sudden onset of dyspnea and cyanosis).

• Throughout therapy, listen to the patient’s fears and concerns, and answer any questions he may have. Remain with him during periods of extreme stress and anxiety. Encourage him to identify actions and care measures that help make him comfortable and relaxed. Perform these measures, and encourage the patient to do so as well.

• Whenever possible, include the patient in care decisions, and include family members in all phases of the patient’s care.

Pneumonia

Pneumonia is an acute infection of the lung parenchyma that commonly impairs gas exchange. The prognosis is generally good for people who have normal lungs and adequate host defenses before the onset of pneumonia; however, pneumonia is the sixth leading cause of death in the United States.

CAUSES AND INCIDENCE

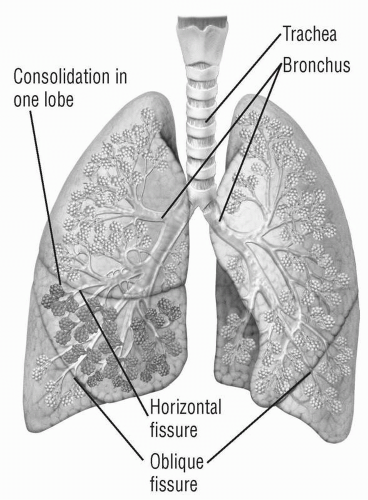

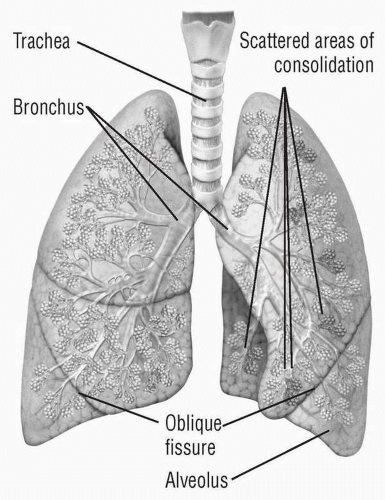

Pneumonia can be classified in several ways. Classification by microbiologic etiology includes viral, bacterial, fungal, protozoan, mycobacterial, mycoplasmal, and rickettsial pneumonia. Classification by location looks at the part of the anatomy affected: Bronchopneumonia involves distal airways and alveoli; lobular pneumonia, part of a lobe; and lobar pneumonia, an entire lobe. (See Pneumonia in two locations.) Classification by type focuses on whether the pneumonia is primary or secondary: Primary pneumonia results from inhalation or aspiration of a pathogen and includes pneumococcal and viral pneumonia; secondary pneumonia may follow initial lung damage from a noxious chemical or other insult (superinfection) or may result

from hematogenous spread of bacteria from a distant focus. Aspiration pneumonia results from inhaling a foreign substance, such as food particles or vomit, into the lungs. Several other classification systems also exist.

from hematogenous spread of bacteria from a distant focus. Aspiration pneumonia results from inhaling a foreign substance, such as food particles or vomit, into the lungs. Several other classification systems also exist.

Predisposing factors for bacterial and viral pneumonia include chronic illness and debilitation, cancer (particularly lung cancer), abdominal and thoracic surgery, atelectasis, common colds or other viral respiratory infections such as acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, chronic respiratory diseases (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, bronchiectasis, and cystic fibrosis), influenza, smoking, malnutrition, alcoholism, sickle cell disease, tracheostomy, exposure to noxious gases, aspiration, and immunosuppressive therapy.

Predisposing factors for aspiration pneumonia include old age, debilitation, artificial airway use, nasogastric (NG) tube feedings, impaired gag reflex, poor oral hygiene, and a decreased level of consciousness.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree