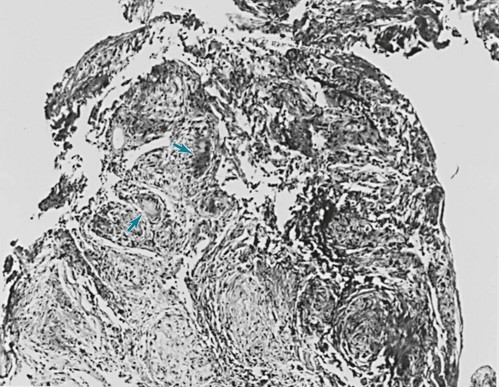

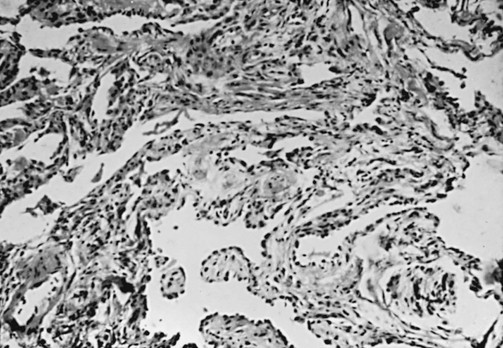

9 A large group of disorders affects the alveolar wall in a fashion that ultimately may lead to diffuse scarring or fibrosis. These disorders traditionally have been referred to as interstitial lung diseases, although the term is somewhat of a misnomer (see Chapter 8). The interstitium formally refers only to the region of the alveolar wall exclusive of and separating the alveolar epithelial and capillary endothelial cells. However, interstitial lung diseases affect all components of the alveolar wall: epithelial cells, endothelial cells, and cellular and noncellular components of the interstitium. In addition, the disease process often extends into the alveolar spaces and therefore is not limited to the alveolar wall. Many authors now prefer the expression diffuse parenchymal lung disease, which is the term generally used in this book. For practical purposes, however, the reader should recognize that the expressions diffuse parenchymal lung disease and interstitial lung disease typically refer to the same group of disorders causing inflammation and fibrosis of alveolar structures. There are more than 150 diffuse parenchymal lung diseases. Table 9-1 lists the most common of these disorders, grouped by broad categories according to whether the underlying etiology of the disease is currently known or unknown. A third category of “mimicking disorders” is included in recognition of the fact that a number of additional well-defined clinical problems can produce diffuse parenchymal abnormalities on chest radiograph. Even though these mimicking disorders often are not included in traditional lists of diffuse parenchymal lung diseases, the clinician must remember to consider them in the appropriate clinical settings. Table 9-1 CLASSIFICATION OF SELECTED DIFFUSE PARENCHYMAL LUNG DISEASES KNOWN ETIOLOGY Resulting from inhaled inorganic dusts (pneumoconiosis [e.g., asbestosis, silicosis]) Caused by organic antigens (hypersensitivity pneumonitis) UNKNOWN ETIOLOGY MIMICKING DISORDERS *Typically associated with focal or multifocal disease rather than diffuse disease. Familiarity with all these diseases is difficult even for the pulmonary specialist, so the novice in pulmonary medicine cannot be expected to amass knowledge regarding each individual entity. Rather, the reader is urged to first develop an understanding of the pathologic, pathogenetic, pathophysiologic, and clinical features common to these disorders. This chapter is an overview of general aspects of diffuse parenchymal lung disease and refers to individual diseases only when necessary. Chapter 10 discusses disorders associated with an identifiable etiologic agent; approximately 35% of patients with diffuse parenchymal lung disease are in this category. Chapter 11 discusses diseases for which a specific etiologic agent has not been identified; the majority of patients with diffuse parenchymal lung disease belong in this second category. These chapters cover only a small number of the described types of diffuse parenchymal disease. The goal throughout is to consider those disorders the reader most likely will encounter. Included in the discussion of diseases of unknown etiology in Chapter 11 are several disorders that affect the lung parenchyma but do not characteristically have diffuse findings on chest radiograph. Examples of diseases in which the findings are more typically focal (or multifocal with more than one area of involvement) include Wegener granulomatosis and cryptogenic organizing pneumonia. The diseases covered in these three chapters are primarily chronic (or sometimes subacute) diseases affecting the alveolar structures. Another group of diseases is associated with acute injury to various components of the alveolus. These latter disorders, which are of clinical importance as causes of acute respiratory failure, are discussed in Chapter 28. Typically, the diffuse parenchymal lung diseases, regardless of cause, have two major pathologic components: an inflammatory process in the alveolar wall and alveolar spaces (sometimes called an alveolitis) and a scarring or fibrotic process (Fig. 9-1). Both features frequently occur simultaneously, although the relative proportions of inflammation and fibrosis vary with the particular cause and duration of disease. The general presumption has been that active inflammation is the primary process and that fibrosis follows as a secondary feature. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a major exception to this generalization. As discussed in Chapter 11, the primary process in IPF appears to be epithelial cell injury and fibrosis (representing an abnormal repair of injury) rather than alveolar inflammation (see Pathogenesis). Figure 9-1 Photomicrograph of diffuse parenchymal lung disease shows markedly thickened alveolar walls. Cellular inflammatory process and fibrosis are present. Compare with appearance of normal alveolar walls in Figure 8-1. One of the most important pathologic features associated with several diffuse parenchymal lung diseases is the granuloma. A granuloma is a localized collection of cells called epithelioid histiocytes, which are tissue cells of the phagocytic or macrophage series (Fig. 9-2). These cells are generally accompanied by T lymphocytes within the granuloma, often forming a rim around it. When cellular necrosis is present in the center of a granuloma, the entity is termed a caseating granuloma, but diffuse parenchymal lung diseases are associated almost exclusively with noncaseating granulomas (i.e., granulomas in which the central area is not necrotic). In contrast, caseating granulomas are characteristically seen in infectious diseases, especially tuberculosis (see Chapter 24, Pathology). The granuloma typically also has multinucleated giant cells that result from fusion of several phagocytic cells into a single large cell with abundant cytoplasm and many nuclei (see Fig. 9-2). Examples of diffuse parenchymal lung disease in which granulomas are part of the pathologic process include sarcoidosis and hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Granulomas are often considered to reflect some underlying immune process, specifically an immune reaction to an exogenous agent. In the case of hypersensitivity pneumonitis, many agents have been identified. However, in the case of sarcoidosis, no specific exogenous agent has been identified. Granulomas in the lung have many other causes (e.g., tuberculosis, certain fungal infections, and foreign bodies), but they are not covered here because the granulomas are generally not associated with diffuse parenchymal lung disease. This chapter discusses seven pathologic entities subsumed under the broad term idiopathic interstitial pneumonias: (1) usual interstitial pneumonia, (2) desquamative interstitial pneumonia, (3) respiratory bronchiolitis interstitial lung disease, (4) nonspecific interstitial pneumonia, (5) acute interstitial pneumonia, (6) cryptogenic organizing pneumonia, and (7) lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia. This section briefly describes the pathologic characteristics defining these seven entities. Chapter 11 focuses on a broader consideration of the more important clinical counterparts of some of them. An important clinical branch point is distinguishing between UIP and the other conditions, because UIP typically carries a worse prognosis. Usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) is characterized by patchy areas of parenchymal fibrosis and interstitial inflammation interspersed between areas of relatively preserved lung tissue (Fig. 9-3). Fibrosis is the most prominent component of the pathology, with focal collections of proliferating fibroblasts called fibroblastic foci. The fibrosis often is associated with honeycombing

Overview of Diffuse Parenchymal Lung Diseases

Pathology

Pathology of Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonias

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Overview of Diffuse Parenchymal Lung Diseases