Chapter 50 Organizing Pneumonia

Definition

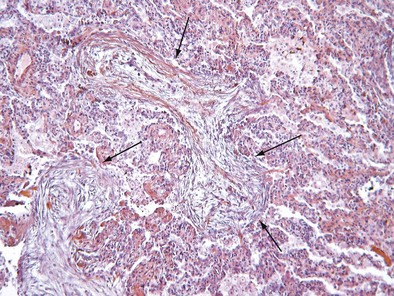

Initially described as the specific histopathologic pattern resulting from organization of an inflammatory exudate in the lumen of alveoli of unresolved pneumonia, OP is characterized by intraalveolar buds of granulation tissue with fibroblasts and myofibroblasts intermixed with loose connective matrix (Figure 50-1). Similar lesions may be present within the lumen of the bronchioles—hence the formerly synonymous term bronchiolitis obliterans with organizing pneumonia (“BOOP”). The latter designation has been abandoned, however, because OP (rather than bronchiolitis) is clearly the major lesion, and furthermore, use of the older term was a potential source of confusion between this entity and bronchiolitis with airflow obstruction occurring, for example, after lung or hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Although the condition is not strictly interstitial, COP is included in the American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society international consensus classification of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias, because of its idiopathic nature and occasional similarities with interstitial pneumonias.

Pathogenesis

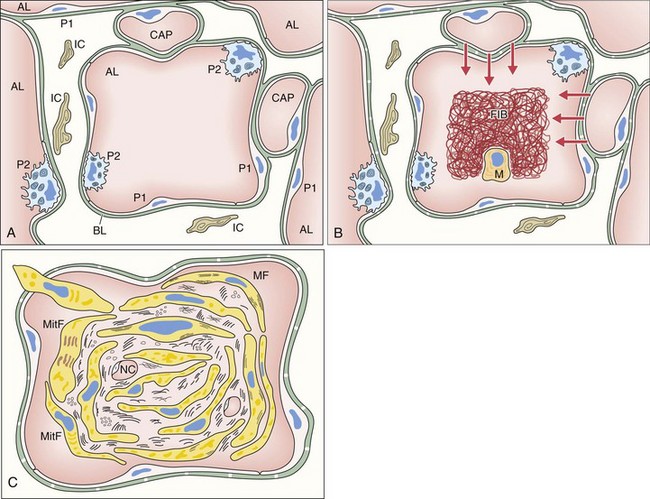

The first event of the sequence leading to the formation of intraalveolar buds is alveolar epithelial injury with necrosis of pneumocytes (especially type I) (Figure 50-2). The epithelial basal laminae are denuded and injured, resulting in formation of gaps. Capillary endothelial injury often is associated. The consequence of alveolar injury is flooding of the alveolar lumen by plasma proteins (permeability edema), including coagulation factors. The balance between coagulation and fibrinolysis is clearly tipped in favor of coagulation (especially because of decreased fibrinolysis), leading to accumulation of fibrin deposits that are soon populated by migratory inflammatory cells and fibroblasts.

Clinical and Imaging Features

Cryptogenic Organizing Pneumonia

Imaging Features

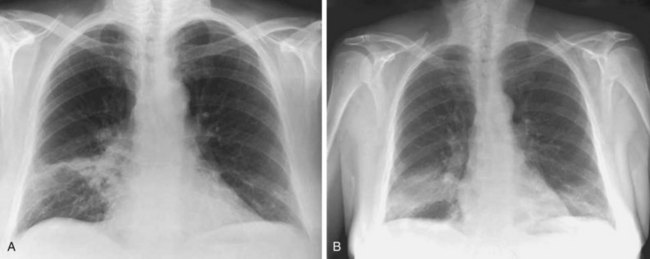

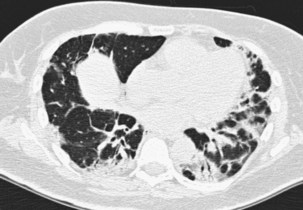

The imaging features of COP may consist of a variety of high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) findings, some of which are highly suggestive of the diagnosis. The most typical imaging pattern in COP consists of multiple patchy alveolar opacities (Figures 50-3 and 50-4). These usually are bilateral, with a subpleural distribution, and sometimes migratory (with attenuation or clearing in some areas and appearance of new opacities in others), ranging in density from ground glass to consolidation with air bronchogram, with no predominance in cranial versus caudal distribution. The size of the opacities may vary, ranging from 1 to 2 cm to involvement of an entire lobe. Consolidation at imaging corresponds pathologically with intraalveolar buds of granulation tissue within the distal air spaces, whereas areas of ground glass opacity reflect the cell infiltration of alveolar wall by inflammatory cells, with some OP changes in the distal air spaces. This imaging pattern with multiple patchy alveolar opacities, especially those of a migratory nature, is so characteristic of typical COP that it should immediately suggest the diagnosis. The main other consideration in the differential diagnosis at this stage is idiopathic chronic eosinophilic pneumonia (in the latter, blood eosinophilia with cell counts usually greater than 1500/µL is present; conversely, nodules may be found more frequently in COP than in chronic eosinophilic pneumonia).

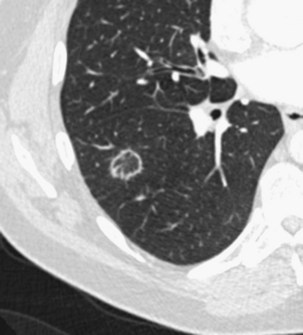

Patchy ground glass opacities frequently are observed, usually associated with consolidation. The reverse halo sign or atoll sign (Figure 50-5), consisting of a circular consolidation pattern (corresponding histopathologically to organizing pneumonia in the distal air spaces) surrounding an area of ground glass opacities (corresponding to alveolar wall inflammation), also is highly suggestive of the diagnosis, although not specific.

The infiltrative (or progressive fibrotic) pattern of OP associates interstitial opacities, with small superimposed alveolar opacities on HRCT (with possible perilobular pattern consisting of bowed or polygonal opacities with poorly defined margins bordering the interlobular septa). Honeycombing is not present. Infiltrative or progressive COP may overlap on both histopathologic and imaging studies with idiopathic nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP), with uniform alveolar and interstitial cellular inflammation (with more or less fibrosis), with the possible presence of foci of organizing pneumonia. Such imaging presentation of OP seems to be particularly frequent in patients with idiopathic inflammatory myopathy (Figure 50-6).

Several less common imaging presentations of COP have been occasionally reported, including multiple nodules, cavitary opacities, perilobular opacities, centrilobular or peribronchovascular ill-defined nodules, bronchocentric areas of consolidation, and linear subpleural bands (Box 50-1). A few mediastinal lymphadenopathies are not rare in COP. Pleural effusion is uncommon.