Traditional care

Enhanced-recovery pathway

Patient education

Variable

Standardized preoperative education protocol

Drain (urine)

Variable

POD #1: removal

Drain (chest tube)

Variable weaning protocol

POD #0: −20 cm suction

POD #3: removal of second chest tube if <450 mL/24 h and no air leak

Nutrition

Surgeon discretion

POD #0: clear fluid

POD #1: diet as tolerated

Activity

Mobility encouraged by team

POD #0: up in chair

POD #1: ambulate in hallway BID

POD #2: ambulate >18 m TID

POD #3: ambulate >75 m TID

Target discharge

None

POD #4

Table 2.2.

Comparison of postoperative care milestones between traditional care and an enhanced-recovery pathway implemented at the McGill University Health Centre (Montreal, Canada) for esophagectomy.

Traditional care | Enhanced-recovery pathway | |

|---|---|---|

Patient education | Variable | Standardized preoperative education protocol |

Drain (urine) | Variable | POD #1 |

Drain (chest tube) | Removal 1 day after resumption of feeds | POD #5 |

Nutrition | Surgeon discretion | POD #3: clear fluid |

POD #5: post-esophagectomy diet | ||

Nasogastric tube | Removal after barium swallow (POD #7) | POD #2 |

Contrast study | POD #7: barium swallow | None |

Target discharge | None | POD #6 |

Fast-track and enhanced recovery pathways in thoracic surgery utilizing a written, multimodal, evidence-based, step-by-step approach to perioperative care are increasingly utilized.

Basic principles include written daily patient education goals, smoking cessation, preoperative physiotherapy, nutrition supplementation, epidural pain control, early mobilization, early feeding, and early drain removal.

Fluid Management

Thoracic surgery does not induce large fluid shifts and intravascular fluid losses compared to other surgical procedures.

Collapse and re-expansion of lung parenchyma, heterogeneous pulmonary compliance in lateral decubitus position, elevated positive pressure ventilatory pressures, or increased pulmonary arterial pressures during single-lung ventilation may induce pulmonary edema that should be monitored and managed postoperatively.

Avoiding fluid overload through judicious, if not restricted, crystalloid and colloid administration intraoperatively and postoperatively is therefore critical in all thoracic patients, especially in patients with limited pulmonary reserve, or with cases requiring increasing pulmonary resection, where the remaining lung is subjected to the entire cardiac output. Fluid restriction while maintaining adequate end-organ perfusion is essential.

Transient hypotension and decreased urine output may be seen due to relative rather than absolute hypovolemia in patients with high thoracic epidural analgesia and should be managed with judicious fluid administration, decreasing epidural dosing as well as its concentration of local anesthetic, and occasionally using low dose vasopressor administration.

Analgesia

Principles of analgesia include [7]:

1.

Multimodal analgesia (e.g., acetaminophen, NSAID and opiate)

2.

Meticulous and continuous attention to each patient’s pain, while dynamically adjusting analgesia, particularly in the first 48 h

3.

Identifying patients at increased risk for postoperative pain

4.

Targeted use of epidural and intercostal blockade

Thoracotomy incisions may be very painful (Fig. 2.1), impairing adequate mobilization, inspiration and expectoration, leading to atelectasis, retention of secretions, infection or worse. Inadequate analgesia contributes to a significant number of postoperative complications in these patients. Inadequate control of pain on postoperative days 1 and 2 is an independent predictor of chronic post-thoracotomy pain. It is thus imperative to control pain effectively and immediately.

Fig. 2.1.

Typical posterolateral thoracotomy incision. Used with permission from the McGill University Health Centre Patient Education Office.

The use of high thoracic epidural anesthesia is associated with improved pain control and decreased risk of pulmonary complications (such as pneumonia, atelectasis, prolonged mechanical ventilation, and re-intubation from respiratory failure), compared to patient-controlled analgesia and narcotic administration [8]. There is also a reduction in opioid consumption.

Thoracoscopic incisions are generally far less painful; however, chronic pain may occur due to levering a trocar on the rib and neurovascular bundle above. Preemptive analgesia with intercostal nerve blocks and local infiltration is an essential adjunct to multimodal oral and intravenous analgesia.

Over-sedation should be avoided when switching patients to oral or subcutaneous narcotics, as this may lead to subsequent hypoventilation and hypercarbia.

Chest Tube Management

Chest tubes are routinely placed in virtually all operations whereby the parietal pleura has been entered to allow for evacuation of air, detection and management of air leaks, and drainage of hemothorax, chylothorax, enteric content, or other types of pleural effusions.

Principles of chest tube placement include being positioned for optimal drainage (fluid: posterior and basal; air: apical and anterior), with tube caliber directed at expected output (large-bore chest tube for sanguinous fluid; pigtail for air and serous fluid).

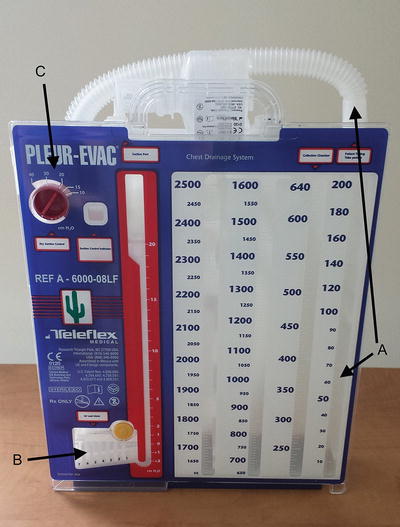

Postoperatively, the patient is asked to voluntarily cough or perform a Valsalva’s maneuver and the water sealed chamber is observed for bubbles (Fig. 2.2). The fluid level in the water chamber should move up and down with deep respiration and coughing.

Fig. 2.2.

Chest tube collection chamber unit. (a) Collection chamber, (b) water seal, (c) suction.

Stationary fluid level in the water seal indicates either intra-thoracic or extra-thoracic tube blockage.

Large swings in the fluid level indicate the presence of a large residual pleural space.

Persistent air leak can be detected by suddenly placing (or increasing) the chamber on suction and observing a sudden rush of air through the system. For patients with small air leaks, the chest tube can be clamped for a couple of hours and then unclamped while on vacuum suction to observe the sudden rush of air; however, clamping overnight is neither necessary nor advisable.

Suction:

Placement of chest tubes on suction rather than water seal after lung resection has not been shown to affect the duration of chest tube, duration of hospital stay, or duration of air leak. However, placing chest tube on suction is associated with a lower incidence of pneumothorax after pulmonary resection [14, 15].

As a principle of management, the minimal suction to achieve intended pleural drainage objectives is optimal.

Chest tube placed in post-pneumonectomy patients should not be on suction due to the risk of mediastinal shift and cardiac herniation.

Removal:

The ideal volume drainage to predict safe removal of chest tubes is unknown. 200 mL/24 h with no air leak is commonly quoted as the threshold for removal; however, there is no evidence to support this.

Chest tubes can be safely removed with drainage volumes of up to 500 mL/24 h without increasing the risk of fluid re-accumulation [16, 17].

Commonly, the target removal date of the second tube after a lobectomy is on day 3 if there is <300 mL of non-chylous fluid in 24 h with no air leak.

Chest tubes should be removed sequentially and each tube should be removed while off suction, with simultaneous application of an occlusive dressing to prevent air entry during its removal.

Respiratory Care

It is imperative for patients to maintain the ability to deliver an effective cough (pulmonary toilet) and to maintain good bronchial hygiene.

Incisional pain can lead to significant chest wall splinting, preventing proper airway clearance of secretions and mucus plugs. This is further exacerbated by a strong smoking history and chronic bronchitis.

Placing a pillow over the incision while coughing reduces pain.

Early ambulation, fluid restriction, aggressive pain control, chest physiotherapy, and prevention of over-sedation with narcotic medications all contribute to a better pulmonary recovery in the postoperative period.

Nasotracheal suctioning, flexible bronchoscopy, mechanical ventilation may be required, especially in patients with poor preoperative pulmonary function.

Other supportive therapies include (as necessary):

Humidified oxygen

Bronchodilators

N-acetylcysteine

Diuretics

High flow, high humidity oxygen

Postoperative Complications

The Thoracic Morbidity and Mortality (TM&M) classification is a system to standardize and grade the presence and severity of surgical complications after non-cardiac thoracic surgery (available at: http://www.ottawatmm.org[18])

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree