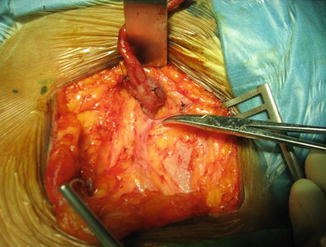

Fig. 7.1

Preoperative mapping of the veins

3.

Mapping the local varices and blow outs in the extremity. This is again done with the patient in the standing position. Total extirpation of the marked varices would improve the final cosmetic appearance of the limb.

4.

Documenting the ankle brachial index to rule out ischemia.

Perioperative thrombosis prophylaxis is not recommended by the American Venous Forum guidelines for patients who do not have additional thromboembolic risk factors. Early and frequent ambulation is suggested. Low-molecular-weight heparin as prophylaxis is recommended for patients with extra risk factors [4].

High Ligation: The Actual Procedure

The term indicates ligation and division of the GSV at its confluence with the common femoral vein (CFV) along with ligation and division of all upper GSV tributaries [1]. The patient is positioned on the table with a Trendelenburg tilt. The limb to be operated is slightly abducted and externally rotated and the knee joint slightly flexed and supported on a roll.

Siting the incision at the appropriate level is a crucial step. One of the common errors is to site the incision too low. According to textbooks of anatomy, the SFJ is located 4 cm below and lateral to the pubic tubercle [9]. During surgery, it is found to be much higher. We make a transverse incision of sufficient length, with its center located 2 cm below and lateral to the pubic tubercle. This incision is cosmetically pleasing and gives a good exposure of the SFJ and all the terminal tributaries. The hockey stick incision described by Dodd and Cockett gives an excellent exposure, but such extensive exposure is not really needed.

There are three basic steps involved in the surgery:

1.

Exposure of the terminal 7–10 cm of the trunk of the GSV and exposure of the SFJ

2.

Control of the terminal tributaries

3.

Making the high ligation

The location of the SFJ is confirmed by displaying the anterior surface of the common femoral vein. Another useful landmark is the superficial external pudendal artery. It runs along the curved lower border of the fossa ovalis, usually posterior to the trunk of the GSV. In a small subset of patients, this vessel runs anterior to the GSV. Its pulsation can be made out and this is a useful pointer to the position of SFJ (Fig. 7.2).

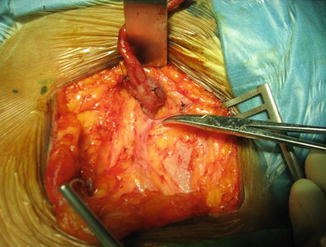

Fig. 7.2

SFJ location. Note the position of the superficial external pudendal artery and the CFV

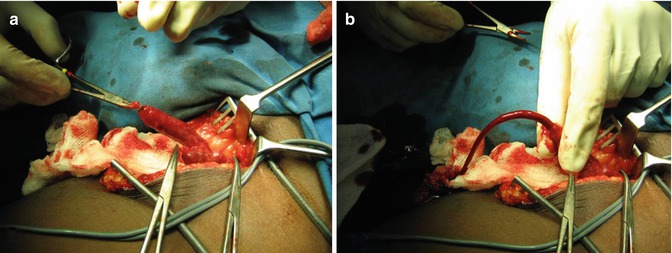

The tributaries to be controlled include the named terminal tributaries – superficial circumflex iliac, superficial epigastric, and external pudendal veins (Fig. 7.3).

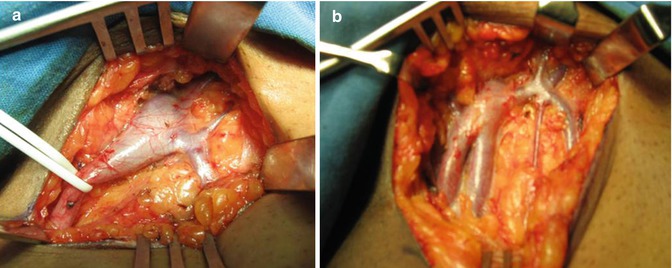

Fig. 7.3

Anatomy of SFJ displayed during high ligation. Note the variations in the position and distribution of tributaries. (a) Distribution of tributaries are displayed. (b) Bifid GSV with a different pattern of tributaries

The anterior accessory saphenous vein and posterior accessory saphenous vein in the thigh are also controlled. Hidden tributaries entering on the posterior aspect of the GSV may be evident by transecting the GSV at a point 7–10 cm from the SFJ and turning the proximal stump upward. The deep external pudendal vein may join the GSV on its posterior aspect close to the femoral vein. Sometimes this vessel can enter the femoral vein also [2]. The tributaries are ideally controlled beyond their secondary branch [10].

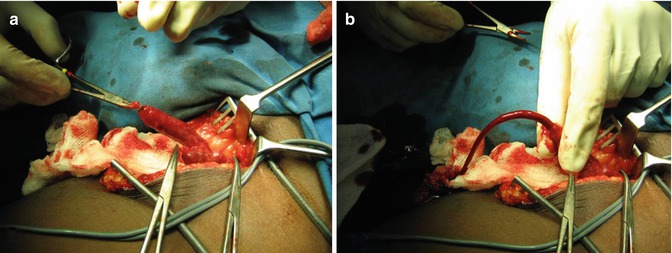

Confirming Reflux at SFJ: We always confirm reflux at the SFJ by the intraoperative test for SF incompetence. For this, the GSV is divided about 7–10 cm from the SFJ between two bulldog clamps. The bulldog clamp controlling the proximal end is released under control. If the SFJ is incompetent, there is a brisk bleed back from the divided proximal stump even as an arterial flow [11] (Fig. 7.4).

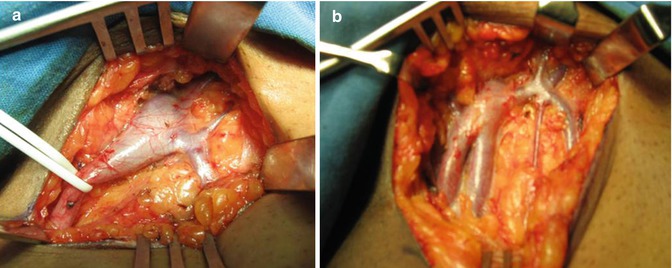

Fig. 7.4

Intraoperative test for SFJ incompetence. (a) Transected stump of GSV controlled with a clamp. (b) Clamp released. Note the brisk bleed back

The SFJ is ligated with double ties with nonabsorbable sutures. The second tie may be a transfixing ligature. The stump should be about 1–2 cm long. Too short a stump has a risk of slipping of ligature. Too long a stump can produce a cul-de-sac. Covering the stump with a patch of PTFE graft is recommended by some to prevent neovascularization. This is not recommended in the guidelines of the American Venous Forum [4]. The distal end is removed along with stripping. The wound is closed with a suction drain after completing the stripping procedure.

Two problems can add on to the technical difficulties:

Saphena varix: This is a localized, circumferential, or anterior wall dilatation of the terminal portion of the GSV. It results from reflux at SFJ. During straining and coughing, a jet of refluxing blood from the femoral vein strikes the anterior wall of the GSV at a point 7–10 cm from the junction. This is the reason why saphena varix is seldom located at the exact SFJ. The varix is thin walled and when torn can bleed profusely (Fig. 7.5)

Fig. 7.5

Saphena varix

Enlarged inguinal lymph nodes: May be a difficult problem especially in an ulcerated limb. The dissection of the vein should be kept away from the nodes. Injury to the nodes can cause bleeding and postoperative lymphatic leak.

Our Observations During High Ligation

In a series of 80 dissections in the groin for high ligation of the groin, we made the following observations:

1.

SFJ was on average situated 2.6 cm below and 3 cm lateral to the pubic tubercle.

2.

The number of tributaries varied from 2 to 7.

3.

Superficial external pudendal artery could be identified in 90 % of the limb. The vessel was coursing anterior to the GSV in only two limbs.

4.

Saphena varix was seen in 25 % of the limbs, 6.25 cm (mean) from the termination.

Stripping of the Trunk of GSV

The term stripping indicates removal of a large segment of the vein, the GSV or SSV, by means of a device. This is an essential step in the surgery of GSV varicose veins. It is recognized that the recurrence rate can be minimized by including this procedure [4]. One of the important causes of REVAS is presence of refluxing channels [12].

Total stripping from groin to ankle is not practiced currently because of the risk of damage to the saphenous nerve in the leg and the high incidence of postoperative saphenous neuralgia [4, 10]. Moreover, even total stripping does not disconnect incompetent ankle perforators [2].

Short-segment stripping from the groin to below-knee level is the recommended option now. This procedure removes the incompetent thigh segment of the GSV (the below-knee segment of the GSV is usually competent in the majority of patients); at the same time, it avoids injury to the saphenous nerve.

Perforate-invaginate stripping (PIN stripping) minimizes these events and is the preferred option. In conventional intraluminal stripping, the stripped vein gets rolled over and wrapped around the acorn-shaped stripper head to form a thick hard “plug.” The tissue trauma along the stripped tract can be considerable. Again, a large exit wound is needed. The PIN stripping uses an instrument with a miniscule head and flat neck. It is a minimally invasive procedure and can be carried out even in an office setting under local anesthesia. The technique was introduced by Oesch in 1993, initially for short saphenous varicosity [13]. A flexible Codman disposable stripper without the removable acorn can also be used for invagination stripping [4].

To reduce bleeding during stripping, the limb is elevated and as the stripping progresses, compression bandages are applied. Infiltration of the perivenous space by tumescent anesthesia is recommended by Gloviczki et al. to reduce bleeding [4].

Cryostripping of the GSV: This is recommended to decrease hemorrhage from the stripped tract. The procedure needs the use of a cryosurgical system. After high ligation, the cryoprobe is passed down to the desired level around knee and freezing initiated. The saphenous vein is invaginated by pulling the vein with force. The incidence of post stripping bruising and complications were less compared to standard stripping [14].

Phlebectomy

This procedure is aimed at excising local blowouts and bulging veins. It improves the cosmetic appearance of the limb, an important goal of treatment of varicose veins. Meticulous preoperative mapping of the veins is essential to achieve optimum outcome.

Cosmetic phlebectomy: The procedure was described by Dodd and Cockett. Through 1–2 cm long vertical incisions, large segments of the veins are excised. It is compared to birds picking out worms from burrows and hence is also called “worming.” The wounds are sutured. Vertical incisions in the extremities are preferred between joints since they fall in the natural Langer’s line. The resultant scars are cosmetically acceptable [2].

Ambulatory phlebectomy: The procedure is also known as stab or hook or mini phlebectomy. It involves the avulsion or removal of varicose veins through small 1–2 mm stab wounds made by a number 11 blade. Avulsion of varicose veins is performed with hooks (Muller or Oesch) or forceps. The procedure can be performed under tumescent local anesthesia. The skin wounds are approximated with steristrips. Thigh-length compression stockings/bandages are applied on completion of the procedure [4].

Light assisted stab phlebectomy: Lawrence and Vardanian have reported a newer technique stab phlebectomy. It combines transillumination, tumescent anesthesia, and stab phlebectomy using special surgical instruments. It provides better visualization and more rapid and complete removal of veins [15].

Transilluminated powered phlebectomy (TIPP): This is a useful technique for the removal of larger clusters of varicosities. The procedure is done under spinal, epidural, or general anesthesia. Tumescent anesthesia is added with infusion of dilute lidocaine with epinephrine. Transillumination is achieved by a specially designed cannula. Vein extraction is done using a resector [16]. The procedure is combined with HL/S. The advantages claimed include a decrease in the number of incisions and much faster removal of a large amount of varicose vein tissue [4].

Preservation of the GSV

The CHIVA Technique: Ambulatory Conservative Hemodynamic Management of Varicose Veins

Basically this technique preserves the GSV to facilitate venous drainage into the deep veins. The tributaries are controlled by phlebectomy. This is to reduce the hydrostatic pressure in the GSV and tributaries. The drainage function of the superficial veins is maintained by a reversed flow [4]. CHIVA is an example of duplex-controlled surgery. The aim of CHIVA is to treat varicose veins by preserving the GSV and utilizing its drainage function by eliminating reflux points. A basic requirement is to make a detailed study by duplex scan and determine the sites of reflux [17].

The surgical approach is planned on the basis of duplex finding. A common CHIVA technique includes ligation of the incompetent saphenous vein; ligation, division, and avulsion of only the incompetent tributaries; maintaining patency of the saphenous trunk and the competent saphenous tributaries; and maintaining venous drainage through reentry perforators [18]. In contrast, the conventional procedure of HL/S disconnects competent tributaries and also removes the re entry perforating veins [17].

The ASVAL Technique: Ambulatory Selective Varices Ablation Under Local Anesthesia

The procedure was described by Pitaluga and colleagues and tries to control the disease by eliminating the varicose reservoirs and preserving the incompetent and refluxing saphenous vein. Traditionally it was believed that in primary varicose veins, reflux starts at the confluence of the SFJ and descends progressively downward. This descending hemodynamic concept has been questioned, and it is believed that it can happen the other way round, in an ascending manner. The encouraging results of endovenous techniques where the SF junction is spared tend to support this theory.

A careful preoperative mapping of the reservoir filling sources is carried out by duplex scanning. For this, each segment of the limb is divided into four surfaces, anterior, medial, lateral, and posterior. A total of 32 zones are identified. The areas to be controlled are selected from this on the basis of the scan. The stab avulsion of the tributaries is carried out under local anesthesia. The procedure is recommended for the less evolved form of the disease. Follow-up at 32.4 months revealed reduction of SF reflux with a significant diminution in the diameter of the superficial veins [19].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree