Open Repair of Type B Dissection

Paul R. Crisostomo

Jae S. Cho

Introduction

Aortic dissection is the most common of all acute aortic syndromes and develops when a tear, the “entry point,” occurs in the intima of the aortic wall and blood flows into the media, creating a false flow lumen within the media. The DeBakey classification system anatomically categorizes the dissection based on the primary intimal tear and the extent of the dissection. Type I involves the ascending aorta, the arch, the descending aorta and often the abdominal aorta. Type II involves the ascending aorta, stopping at the level of the arch. It does not involve the left subclavian artery (LSA). Type III involves the aorta distal to the LSA and is limited to descending thoracic aorta (IIIa) or the thoracic and abdominal aorta (IIIb) (Fig. 9.1).

In contrast, the Stanford classification system more simply categorizes the dissection based solely on the presence and location of a false lumen irrespective of the primary intimal tear. Type A dissections involve the ascending aorta, defined from the aortic root to the origin of the brachiocephalic artery. However, the primary intimal tear of a type A could occur in the ascending, transverse arch, or descending aorta, and the dissection may also involve the descending thoracic aorta. Type B dissections occur usually distal to the LSA, but a dissection of the aortic arch is also considered a Stanford type B as it does not involve the ascending thoracic aorta. The Stanford classification has greater clinical relevance as it separates patients who always benefit from urgent surgical repair (type A) from patients who may not require emergent intervention (type B). The DeBakey classification, on the other hand, has more relevance when analyzing the outcomes of thoracic endovascular aortic repair (TEVAR) for aortic dissection, that is, Type IIIa versus IIIb. Complete false lumen thrombosis is much more likely to occur with DeBakey Type IIIa extent compared to Type IIIb variant.

In Type B aortic dissections (TBAD), the initial tear commonly occurs within a ruptured plaque. In severely atherosclerotic aorta, the fibrotic media may actually limit the extension of false lumen. The incidence of acute TBAD is 2.1 per 100,000 persons. As the false channel progresses distally, it may exert a significant mechanical stress on aortic true lumen

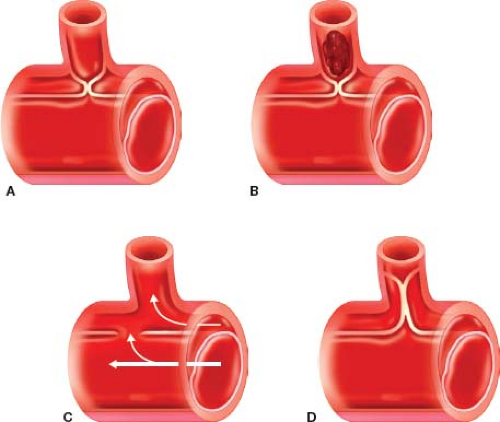

and/or the branch vessels along its path. When perfusion through the branch vessels is compromised, malperfusion syndrome develops, which is observed in 25% to 50% of all TBADs. In malperfusion due to static obstruction, the dissection flap or intimal tear extends into a branch vessel ostium, leading to hypoperfusion or distal thrombosis of the involved vessel. Restoration of flow through the true lumen proximally is not sufficient to restore flow through the involved branch vessel; either bypass grafting or stenting of the vessel is normally required. Often, however, false lumen reentry tear may restore blood flow into the true lumen beyond the obstruction. In malperfusion due to dynamic obstruction, compression of the true lumen or the dissection flap prolapse into the orifice of the vessel results in ischemia. (Fig. 9.2) In the International Registry of Aortic Dissection, malperfusion was noted in about one-third of the patients. Malperfusion syndrome accounts for the majority

of morbidity and mortality in TBADs and often determines the need for surgical intervention of TBAD. Type B dissections without malperfusion have a mortality of 10% at 30 days with medical management alone. In contrast, TBADs with malperfusion have a mortality of 25% at 30 days, and with visceral malperfusion of 50% to 88% at 30 days.

and/or the branch vessels along its path. When perfusion through the branch vessels is compromised, malperfusion syndrome develops, which is observed in 25% to 50% of all TBADs. In malperfusion due to static obstruction, the dissection flap or intimal tear extends into a branch vessel ostium, leading to hypoperfusion or distal thrombosis of the involved vessel. Restoration of flow through the true lumen proximally is not sufficient to restore flow through the involved branch vessel; either bypass grafting or stenting of the vessel is normally required. Often, however, false lumen reentry tear may restore blood flow into the true lumen beyond the obstruction. In malperfusion due to dynamic obstruction, compression of the true lumen or the dissection flap prolapse into the orifice of the vessel results in ischemia. (Fig. 9.2) In the International Registry of Aortic Dissection, malperfusion was noted in about one-third of the patients. Malperfusion syndrome accounts for the majority

of morbidity and mortality in TBADs and often determines the need for surgical intervention of TBAD. Type B dissections without malperfusion have a mortality of 10% at 30 days with medical management alone. In contrast, TBADs with malperfusion have a mortality of 25% at 30 days, and with visceral malperfusion of 50% to 88% at 30 days.

Figure 9.1 Classification of aortic dissection. DeBakey I (60%), II (10–15%), IIIa, IIIb (25% to 30%). Stanford A, B. |

Complicated acute TBADs, those with malperfusion syndrome of the viscera, lower extremities, spinal cord or rupture/imminent rupture, should be intervened emergently. Kidney malperfusion, by itself without any other organ malperfusion, usually does not warrant an emergent intervention. The aggregate function of both kidneys must be taken into account in the decision making process. In the setting of impending renal failure with rising creatinine and refractory hypertension, renal intervention may be performed in a more elective, nonemergent setting. Retrograde dissection into aortic arch and ascending aorta may occur in 2% to 10% of TEVARs performed for complicated TBAD; this also requires urgent or emergent open surgical repair.

TEVAR has completely changed the treatment paradigm for TBAD with its superior outcomes compared with open repair. In September 2013, the Food and Drug Administration approved the Gore Conformable TAG Thoracic Endoprosthesis for repair of acute and chronic Type B dissections. The majority of practitioners would apply TEVAR for acute complicated TBAD when anatomically and technically feasible.

Rarely, open surgical intervention is indicated in acute settings. Anatomical features not favorable for TEVAR include inadequate proximal seal (at least 2 cm), small or occluded iliac access, acute angle in young patients, and narrow aortic diameter in young patients. Concern for stroke, TEVAR collapse, and retrograde type A dissection are other situations where TEVAR may not be ideal. The latter is especially the case in patients with connective tissue disorders. In these scenarios, open repair of complicated acute Type B dissection is indicated.

Chronic dissections weaken the thoracic aorta and increase risk for rapid or late aneurysmal degeneration. Repair is indicated for aneurysmal degeneration of the aorta to >5.5cm, symptomatic dilatation, and rapid expansion defined as >1 cm/yr. Other indications for surgical repair include recalcitrant pain, refractory hypertension, dissection progression in length, pseudoaneurysm, aortic arch involvement, younger patient without comorbidity, and Marfan’s syndrome.

Although TEVAR for treating chronic TBAD has been reported in multiple single-center and registry-based series, its role remains controversial. A rigid chronic dissection flap may prevent reexpansion of the true lumen, while multiple distal reentry points may perpetuate flow into and pressurization of the false lumen. When aneurysmal degeneration extends into the abdominal aorta, TEVAR offers a very limited chance for cure. Direct open repair may offer the only realistic option for durable repair.

The media of the aorta has a rich supply of nerve endings. As such, patients with dissection present with acute onset of sharp chest or back pain, especially when it occurs in relatively healthy aorta. When the aorta is involved with atherosclerotic aorta as is commonly seen in Type B dissection, the pain may be reduced in its sharpness and severity. The pain is typically described as sharp, severe upper back pain that extends down to the lower back and even to the groins, depending on the extent of dissection and involvement of the iliac vessels.

Symptoms of malperfusion are dependent on the organs affected. Abdominal pain, nausea, and emesis may indicate compromised mesenteric blood supply. Flank pain may develop in the setting of kidney ischemia. Cold and pulseless lower extremity results when iliac or femoral vessels are affected. Paraplegia, although rare, may manifest when spinal arteries thrombose or are sheared off by intramural hematoma. Acute paralysis is usually accompanied by spinal shock, which may make initial evaluation more difficult. Rupture is a relatively rare event occurring in <5% of cases.

Computed tomography angiography (CTA) is the diagnostic imaging modality of choice and allows definition of true and false lumen, intra-arterial thrombus, and malperfusion.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) time-of-flight angiography (MRA) can be performed without contrast, which has clear benefit in patients with contrast allergy, renal dysfunction, or those concerned with long-term radiation effects. However, MRA spatial resolution is less precise, calcification is less well defined, prolonged imaging acquisition time requires hemodynamic stability and lack of claustrophobia, and is contraindicated in the presence of Swan-Ganz catheters and other internal metallic hardware. Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) is less sensitive for the detection of aortic dissection in even experienced operator’s hands, but more sensitive in detecting cardiac pathophysiology (coronary artery occlusion, aortic insufficiency, cardiac tamponade) and is thus a frequently utilized intraoperative or preoperative adjunct. Aortography has many pitfalls such as lack of false lumen visualization and poor sensitivity and is no longer used if the aforementioned imaging modalities are available. Intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) is an essential component to TEVAR repair for identification of true and false lumen, but is not necessary in open Type B repair.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) time-of-flight angiography (MRA) can be performed without contrast, which has clear benefit in patients with contrast allergy, renal dysfunction, or those concerned with long-term radiation effects. However, MRA spatial resolution is less precise, calcification is less well defined, prolonged imaging acquisition time requires hemodynamic stability and lack of claustrophobia, and is contraindicated in the presence of Swan-Ganz catheters and other internal metallic hardware. Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) is less sensitive for the detection of aortic dissection in even experienced operator’s hands, but more sensitive in detecting cardiac pathophysiology (coronary artery occlusion, aortic insufficiency, cardiac tamponade) and is thus a frequently utilized intraoperative or preoperative adjunct. Aortography has many pitfalls such as lack of false lumen visualization and poor sensitivity and is no longer used if the aforementioned imaging modalities are available. Intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) is an essential component to TEVAR repair for identification of true and false lumen, but is not necessary in open Type B repair.

Medical therapy is the initial therapy of choice for uncomplicated TBAD and for complicated TBAD without life-threatening malperfusion or rupture. It consists of beta blockers and vasodilators. Beta blockers reduce blood pressure and minimize aortic wall stress, thereby retarding propagation of the dissection, reducing the risk or rupture, controlling pain, and stabilizing the dissected aorta. In the early phase, intravenous agents such as esmolol or labetalol are used. Adjunctive calcium channel blockers can be used. Use of nitroprusside is limited in the early phase for a short duration to stabilize the patients. Pain management may also aid in blood pressure control.

Once stabilized, oral agents are used to maintain the blood pressure and heart rate in the desired range. It is not unusual for these patients to have malignant hypertension and require a combination of antihypertensives consisting of beta blockers, calcium channel blockers, angiotensinogen-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, diuretics, and alpha-2 agonists. However, many of these patients are affected with atherosclerosis in cerebrovascular, mesenteric, renal and lower extremity beds, and require a higher pressure head to maintain pressure to these end organs. In such circumstances, a balancing act is required between minimizing aortic stress and perfusion of distal organs.

Preoperative cardiac evaluation is essential as greater than 25% of patients will have concomitant coronary artery disease. Electrocardiogram (ECG), TEE, and cardiologist evaluation are often part of the preoperative workup, but coronary arteriography is not universally required. In patients who require coronary artery bypass prior to TBAD open repair, preservation of the left internal mammary artery may allow aortic cross-clamping proximal to the LSA as well as maintain important collateral blood supply to the spinal cord.

The risk of spinal cord ischemia increases dramatically with open direct aortic repair in the setting of acute dissection (19% acute vs. 2.9% chronic). Thus CSF drainage is mandatory.

A variety of other tests are also essential for preoperative workup of open aortic repair. Patients with aortic dissection may have genetic mutations associated with early onset occlusive vascular disease. Carotid duplex, extremity arterial Doppler, and extremity arterial duplex may be useful noninvasive screening modalities. Pulmonary function tests and arterial blood gases may alert the need for perioperative bronchodilators, systemic steroids, or antibiotics as well as provide additional incentive for smoking cessation. Careful evaluation of the patient’s renal function is mandatory because preoperative renal disease is a well-recognized predictor of mortality, postoperative renal failure, and paralysis.

Prophylactic antibiotics are dosed in the usual fashion prior to incision. Nasogastric tube, Foley catheterization, central venous access, arterial line monitoring at the minimum are also obtained. Intraoperative TEE monitoring is also critical.

Open Direct Aortic Repair

Open direct aortic repair is rarely necessary acutely in the current era. It is indicated when TEVAR is not available or anatomically possible, in complicated TBAD with retrograde aortic dissection where hybrid procedure (arch debranching and TEVAR) is not desirable, and aortic rupture. In rare instances of acute aneurysmal dilation of the aorta, open direct aortic repair is also indicated. For malperfusion, placement of a short descending aortic graft to replace the primary intimal tear site and to restore blood flow distally in the true lumen or both true and false lumen, depending on the status of reno-visceral perfusion, is the goal. For rupture or impending rupture, the entire aorta from the entry tear to the rupture site is resected.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree