The search for complementary treatments in primary prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a high-priority challenge. Grape and wine polyphenol resveratrol confers CV benefits, in part by exerting anti-inflammatory effects. However, the evidence in human long-term clinical trials has yet to be established. We aimed to investigate the effects of a dietary resveratrol-rich grape supplement on the inflammatory and fibrinolytic status of subjects at high risk of CVD and treated according to current guidelines for primary prevention of CVD. Seventy-five patients undergoing primary prevention of CVD participated in this triple-blinded, randomized, parallel, dose–response, placebo-controlled, 1-year follow-up trial. Patients, allocated in 3 groups, consumed placebo (maltodextrin), a resveratrol-rich grape supplement (resveratrol 8 mg), or a conventional grape supplement lacking resveratrol, for the first 6 months and a double dose for the next 6 months. In contrast to placebo and conventional grape supplement, the resveratrol-rich grape supplement significantly decreased high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (−26%, p = 0.03), tumor necrosis factor-α (−19.8%, p = 0.01), plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1 (−16.8%, p = 0.03), and interleukin-6/interleukin-10 ratio (−24%, p = 0.04) and increased anti-inflammatory interleukin-10 (19.8%, p = 0.00). Adiponectin (6.5%, p = 0.07) and soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (−5.7%, p = 0.06) tended to increase and decrease, respectively. No adverse effects were observed in any patient. In conclusion, 1-year consumption of a resveratrol-rich grape supplement improved the inflammatory and fibrinolytic status in patients who were on statins for primary prevention of CVD and at high CVD risk (i.e., with diabetes or hypercholesterolemia plus ≥1 other CV risk factor). Our results show for the first time that a dietary intervention with grape resveratrol could complement the gold standard therapy in the primary prevention of CVD.

Approximately 2 decades ago, red wine consumption was found to be the explanation for the so-called French paradox, i.e., a low mortality from cardiovascular disease (CVD) in France compared to that in other countries despite sharing CVD risk factors. Initially, the polyphenol resveratrol was identified as the potential cause of the beneficial properties of red wine. Abundant preclinical evidence (in vitro and animal models of human CVD) using high resveratrol concentrations has shown CV benefits by increasing insulin sensitivity and decreasing ischemia heart disease, heart failure, and hypertension. Despite the expectation derived from this molecule’s preclinical benefits, corroboration through long-term randomized human clinical trials is lacking. Our main aim was to investigate the effects of a dietary resveratrol-rich grape supplement on the inflammatory and fibrinolytic status of subjects at high risk of CVD and treated according to current guidelines for primary prevention.

Methods

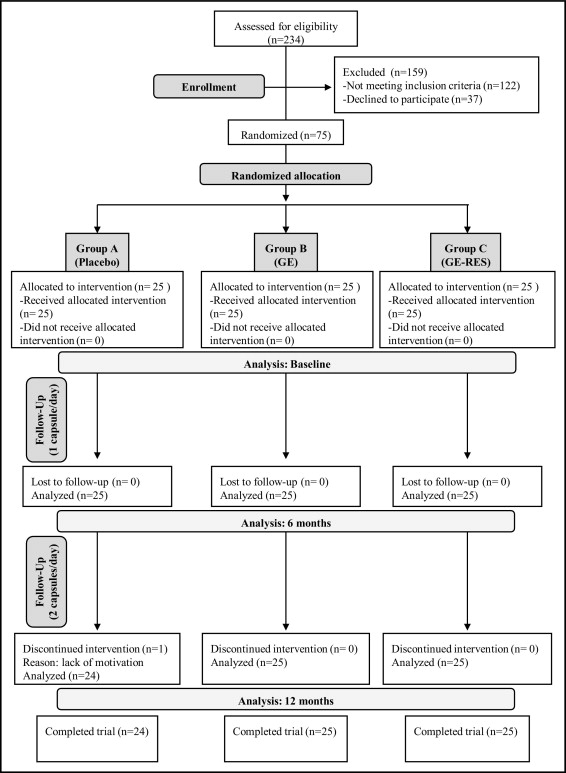

The study was a randomized, triple-blinded, placebo-controlled trial with 3 parallel arms, i.e., grape extract containing resveratrol 8 mg (GE-RES), a grape extract (GE) with a similar polyphenolic content but lacking resveratrol, and placebo (maltodextrin). Patients undergoing primary CVD prevention were recruited from the Morales Meseguer University Hospital Cardiology Service (Murcia, Spain). Inclusion criteria were patients 18 to 80 years old on statin treatment for >3 months before inclusion and diabetes mellitus or hypercholesterolemia plus another CV risk factor such as arterial hypertension, active tobacco smoking, or overweight/obesity (body mass index >30 kg/m 2 ). Exclusion criteria were pregnancy, an age <18 or >80 years, or documented CV or cerebrovascular diseases, or habitual intake of food supplements (herbal preparations, “antioxidant” pills, etc.), or infectious disease or neoplastic disease or other known chronic pathology. In total 75 subjects (34 men and 41 women) of 234 eligible patients were randomly distributed in 3 groups (25 patients each), i.e., A (placebo), B (GE), and C (GE-RES) using a computer-generated random-number sequence ( Figure 1 ) . Table 1 presents baseline characteristics of patients at inclusion. The primary end point was change in high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) level from baseline to 12 months. Sample size was calculated to detect a difference of 1 mg/L with a power of 80% and a 2-sided test with an alpha of 0.05 on the variable hs-CRP. The study was included in the Spanish National Research Project BFU2007-60576 and conformed to ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki and its amendments. The design (reference 02/07) was approved by the clinical ethics committee at Morales Meseguer University Hospital and by the Spanish National Research Council’s bioethics committee (Madrid, Spain). The trial was explained to all patients who provided written informed consent. The trial was registered at http://clinicaltrials.gov as NCT01449110 and was conducted from April 2009 through March 2011.

| Variable | Groups | p Values at Baseline | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A (n = 25) | B (n = 25) | C (n = 25) | A vs B | A vs C | B vs C | |

| Age (years) | 63 ± 9 | 56 ± 11 | 62 ± 9 | 0.04 ⁎ | 0.99 | 0.06 |

| Men | 13 (52%) | 14 (56%) | 7 (28%) | 0.84 | 0.10 | 0.07 |

| Body mass index (kg/m 2 ) | 29 ± 3 | 31 ± 5 | 32 ± 9 | 0.11 | 0.67 | 0.31 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 129 ± 18 | 132 ± 18 | 130 ± 16 | 0.99 | 0.73 | 0.71 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 76 ± 10 | 77 ± 11 | 76 ± 9 | 0.66 | 0.85 | 0.54 |

| Heart rate (beats/min) | 68 ± 10 | 67 ± 9 | 66 ± 8 | 0.90 | 0.52 | 0.60 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 9 (36%) | 12 (48%) | 11 (44%) | 0.51 | 0.82 | 0.67 |

| Hypertension | 23 (92%) | 20 (80%) | 22 (88%) | 0.55 | 0.55 | 1.00 |

| Smoking | 13 (52%) | 16 (64%) | 12 (48%) | 0.71 | 0.55 | 0.34 |

| Antiplatelet therapy | 10 (40%) | 14 (56%) | 11 (44%) | 0.69 | 0.83 | 0.55 |

| Acetyl salicylic acid | 9 (36%) | 13 (52%) | 10 (40%) | 0.68 | 0.83 | 0.53 |

| Clopidogrel | 1 (4%) | 1 (4%) | 1 (4%) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Statins | 25 (100%) | 25 (100%) | 25 (100%) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Atorvastatin | 20 (80%) | 18 (72%) | 15 (60%) | 0.40 | 0.30 | 0.48 |

| Rosuvastatin | 1 (4%) | 3 (12%) | 3 (12%) | 0.32 | 0.32 | 1.00 |

| Pravastatin | 2 (8%) | 2 (8%) | 6 (24%) | 1.00 | 0.26 | 0.26 |

| Fluvastatin | 2 (8%) | 2 (8%) | 1 (4%) | 0.65 | 0.32 | 0.56 |

| Calcium channel blockers | 9 (36%) | 7 (28%) | 3 (12%) | 0.62 | 0.08 | 0.21 |

| β Blockers | 10 (40%) | 12 (48%) | 10 (40%) | 0.83 | 0.65 | 0.51 |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors | 3 (12%) | 3 (12%) | 1 (4%) | 1.00 | 0.32 | 0.32 |

| Angiotensin II receptor blockers | 18 (72%) | 17 (68%) | 18 (72%) | 0.74 | 0.61 | 0.86 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) | 187 ± 31 | 193 ± 54 | 187 ± 23 | 0.30 | 0.69 | 0.52 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | 121 ± 48 | 121 ± 65 | 124 ± 52 | 0.93 | 0.85 | 0.92 |

| Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (mg/dl) | 106 ± 27 | 114 ± 43 | 110 ± 16 | 0.24 | 0.36 | 0.80 |

| High-density lipoprotein cholesterol (mg/dl) | 55 ± 13 | 53 ± 12 | 54 ± 11 | 0.89 | 0.98 | 0.87 |

| High-sensitivity C-reactive protein (mg/L) | 4.4 ± 4.3 | 3.2 ± 2.5 | 5.0 ± 3.7 | 0.20 | 0.85 | 0.16 |

| Adiponectin (µg/ml) | 14.3 ± 8.1 | 14.8 ± 5.9 | 15.4 ± 9.9 | 0.27 | 0.55 | 0.60 |

| Tumor necrosis factor-α (pg/ml) | 13.4 ± 11.8 | 10.5 ± 10.6 | 16.2 ± 16.2 | 0.43 | 0.46 | 0.14 |

| Interleukin-6 (pg/ml) | 1.6 ± 1.3 | 1.6 ± 1.5 | 1.7 ± 1.1 | 0.91 | 0.84 | 0.76 |

| Interleukin-10 (pg/ml) | 9.8 ± 6.8 | 9.9 ± 6.2 | 9.6 ± 7.8 | 0.41 | 0.86 | 0.29 |

| Interleukin-6/interleukin-10 | 0.28 ± 0.35 | 0.20 ± 0.22 | 0.25 ± 0.31 | 0.68 | 0.40 | 0.60 |

| Interleukin-18 (pg/ml) | 216 ± 131 | 227 ± 145 | 184 ± 117 | 0.92 | 0.88 | 0.82 |

| Soluble intercellular adhesion molecule type 1 (ng/ml) | 364 ± 112 | 353 ± 106 | 342 ± 86 | 0.70 | 0.47 | 0.73 |

| Plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1 (ng/ml) | 17.5 ± 5.2 | 17.1 ± 10.9 | 16.7 ± 6.7 | 0.85 | 0.73 | 0.87 |

| D-dimer (mg/L) | 0.11 ± 0.06 | 0.11 ± 0.08 | 0.13 ± 0.09 | 0.79 | 0.15 | 0.24 |

| Fibrinogen (g/L) | 3.6 ± 0.7 | 3.3 ± 0.5 | 3.7 ± 0.6 | 0.27 | 0.75 | 0.18 |

| γ-Glutamyl transferase (U/L) | 28 ± 13 | 30 ± 22 | 30 ± 26 | 0.35 | 0.83 | 0.29 |

| Aspartate transaminase (U/L) | 25 ± 5 | 27 ± 11 | 27 ± 9 | 0.49 | 0.17 | 0.52 |

| Alanine transaminase (U/L) | 28 ± 10 | 34 ± 20 | 29 ± 15 | 0.36 | 0.79 | 0.54 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (U/L) | 333 ± 51 | 325 ± 43 | 336 ± 33 | 0.84 | 0.99 | 0.85 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (U/L) | 197 ± 58 | 168 ± 43 | 205 ± 85 | 0.13 | 0.98 | 0.11 |

| Creatine phosphokinase (U/L) | 129 ± 69 | 119 ± 44 | 129 ± 83 | 0.80 | 0.61 | 0.81 |

| Glucose (mg/dl) | 121 ± 33 | 119 ± 33 | 115 ± 26 | 0.04 ⁎ | 0.03 ⁎ | 0.76 |

| Glycated hemoglobin (%) | 6.5 ± 1.2 | 6.6 ± 1.2 | 6.2 ± 0.6 | 0.17 | 0.00 ⁎ | 0.15 |

| Thyroid-stimulating hormone (mU/L) | 2.1 ± 1.2 | 2.2 ± 1.4 | 2.2 ± 1.0 | 0.64 | 0.96 | 0.68 |

| Thyroxine (ng/dl) | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 0.11 | 0.68 | 0.24 |

| Bilirubin (mg/dl) | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 0.55 | 0.11 | 0.32 |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 0.57 | 0.28 | 0.55 |

| Urate (mg/dl) | 5.3 ± 1.5 | 5.8 ± 1.2 | 5.7 ± 1.3 | 0.22 | 0.06 | 0.47 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 44 ± 2 | 45 ± 3 | 44 ± 4 | 0.75 | 0.64 | 0.89 |

Placebo, GE, and GE-RES were encapsulated in identical hard gelatin capsules (370 mg) containing 350 mg of the corresponding product plus 20 mg of the excipients magnesium stearate and silicon dioxide. The products were kindly provided by Actafarma S.L. (Pozuelo de Alarcón, Madrid, Spain). This resveratrol-rich GE (Stilvid ® ) is the key ingredient included in the formulation of the commercially available nutraceutical Revidox ® (Actafarma S.L.). GE and GE-RES contained an approximately similar polyphenolic content per capsule, i.e., procyanidins ∼40 mg, anthocyanins ∼25 mg, flavonols ∼1 mg, and hydroxycinnamic acids ∼0.8 mg (determined by high-performance liquid chromatography coupled to mass detection; Supplementary Table 1 , available online). For GE-RES, the GE also contained resveratrol 8.1 ± 0.5 mg per capsule and other resveratrol-derivatives (piceid and viniferins) in trace amounts. Therefore, conventional GE and GE-RES products were ideal to ascertain the possible specific role of resveratrol compared to the remaining grape constituents.

Patients, cardiologists, and scientists in charge of biochemical determinations and statistical analyses were blind to treatments during the trial. Capsule blisters were labeled with the codes A, B, or C (corresponding to placebo, GE, or GE-RES, respectively) and packed in blank boxes with their corresponding codes. Patients were requested to keep their medication ( Table 1 ), habitual lifestyle, and diet throughout the 12-month period. Patients consumed 1 capsule/day in the morning for the first 6 months and 2 capsules/day for the next 6 months to assess a possible dose–response effect. Study product provision was calculated for the entire study. Ten boxes of 60 capsules were provided to each patient. Patients were requested to return the remaining capsules at the end of the study. Compliance was estimated by taking the amount of capsules ingested divided by the amount the patient should have ingested and multiplied by 100. Possible incidences such as digestive problems (intolerance, dyspepsia, nausea, constipation, or diarrhea), muscle pains, allergic reactions to study products, changes in dietary habits, temporary interruption of treatments, febrile processes, etc., were monitored through questionnaires and telephone calls during the study. Patients were asked to annotate the intake of grape-derived products, especially red wine. In addition, patients recorded their diet for 3 days before each blood withdrawal. Questionnaires were collected and checked at the intermediate (6 months) and final (12 months) measurements. Subjects were instructed to fast overnight before each blood collection.

Blood samples were collected from 8:00 to 10:00 a . m . at baseline, 6 months, and 12 months. Corresponding serum or plasma samples were kept at −80°C until analysis. Safety of the trial was assessed by measuring many variables involved in hepatic, thyroid, and renal functions ( Table 1 ). Serum levels of inflammation-related markers were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays using commercially available standard kits according to protocols described by the manufacturers. Interleukin (IL)-6, IL-10, and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) were measured using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits from BioLegend (San Diego, California). IL-18 and soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (sICAM-1) were measured using kits from eBioscience (San Diego, California). For hs-CRP and adiponectin, kits were purchased from AssayPro (Winfield, Missouri). Plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1 (PAI-1) antigen levels were measured in citrated plasma using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits from PeproTech (Rocky Hill, New Jersey). All samples were tested ≥2 times. In addition, markers with statistically significant changes were further repeated to confirm results.

All analyses were performed with SPSS 19.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, Illinois). Analysis of covariance for repeated measurements was conducted to determine mean changes before and after intragroup comparison and postintervention intergroup comparisons. Parameters with skewed distribution were logarithmically transformed for analysis. Results are expressed as mean ± SD. To adjust for within-subject variation and intersubject differences, covariates included in statistical analysis for each marker were age, gender, body mass index, arterial hypertension, smoking, diabetes mellitus, waist circumference, diagnosed hypercholesterolemia, and medication with antiplatelets, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers, calcium channel blockers, and type of statin. Chi-square test was used for baseline comparison of categorical variables. Pearson r correlation was used to measure the strength of association between 2 variables. In all instances, the accepted level of statistical significance was 0.05 with 95% coefficient interval (CI). Marginal statistical differences were acknowledged at p values from >0.05 to 0.1.

Results

Except for age, glucose, and glycated hemoglobin, which showed slightly different initial values among groups ( Table 1 ), no significant differences were observed in characteristics of participants at inclusion. Trial compliance was >96% in all groups. Only 1 patient from the placebo group dropped out after 10 months.

Significant correlations were found at baseline for hs-CRP versus PAI-1 (r = 0.39, p <0.001), IL-6 versus hs-CRP (r = 0.43, p <0.001), TNF-α versus hs-CRP (r = 0.38, p <0.001), adiponectin versus sICAM-1 (r = −0.41, p <0.001), and IL-18 versus sICAM-1 (r = 0.46, p <0.001) in all groups. After randomization, percentages of patients with hs-CRP values >3 mg/L were 54%, 32%, and 48% in the placebo, GE, and GE-RES groups, respectively.

In the placebo group, a slight increase was observed in IL-6 over the first 6 months, which became significant at the end of intervention (0.19 pg/ml, 95% CI 0.05 to 3.7). In contrast, the anti-inflammatory IL-10 decreased after 12 months (−1.1 pg/ml, 95% CI −1.9 to −0.2; Table 2 ), which yielded a borderline significant increase in the proinflammatory IL-6/IL-10 ratio after 12 months ( Table 2 ). Other markers were not significantly altered in the placebo group. In group B (GE), no change was observed in any marker after 12 months of intervention ( Table 2 ). In contrast, in group C (GE-RES), a mean decrease of 1.3 mg/L was observed for hs-CRP, the main primary outcome of this study (95% CI −2.5 to −0.09; Table 2 ). This biomarker decreased in 20 of 25 patients in this group, and the percentage of patients with hs-CRP values >3 mg/L (used for stratification of CVD risk) decreased from 48% at inclusion to 30% at the end of the trial. In contrast, this proportion did not change in the placebo and GE groups. TNF-α and PAI-1 also decreased in the GE-RES group (−3.18 pg/ml, 95% CI −5.3 to −0.7; −2.8 ng/ml, 95% CI −5.2 to −0.2, respectively; Table 2 ). The IL-6/IL-10 ratio decreased (−0.06, 95% CI −1.2 to −0.01) mainly because of the increase of IL-10 (1.9 pg/ml, 95% CI 1.3 to 2.5). sICAM-1 decreased but with marginal significance ( Table 2 ). Adiponectin significantly increased after 6 months (1.4 μg/ml, 95% CI 0.1 to 3.3), but only with marginal significance after 12 months ( Table 2 ). IL-18 decreased over time but not significantly, and IL-6 was unaffected. We next investigated whether all these changes were correlated for each patient within group GE-RES. We found that the decrease of hs-CRP was significantly correlated with decreases of TNF-α (r = 0.52, p = 0.00) and PAI-1 (r = 0.51, p = 0.00). A significant correlation was also found between the decrease of sICAM-1 and the decrease of IL-18 (r = 0.66, p = 0.00) and in the increase of adiponectin and the decrease of sICAM-1 (r = −0.58, p = 0.00). In addition to the significant intragroup changes observed over time, intergroup differences were significant for IL-10 (groups GE vs GE-RES) and for sICAM-1 and PAI-1 (groups placebo vs GE-RES; Table 2 ). Figure 2 shows the impact of each treatment on inflammatory biomarkers and PAI-1 after 6 and 12 months of intervention compared to their baseline values after consumption of 1 capsule/day and 2 capsules/day, respectively. Although some intergroup changes did not reach statistical significance, Figure 2 shows evident intergroup differences for some markers at the end of the trial, namely hs-CRP, TNF-α, and IL-6/IL-10 ratio.

| Marker | Experimental Values After 6 Months | Experimental Values After 12 Months | Intergroup p Values | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A (n = 25) | B (n = 25) | C (n = 25) | A (n = 25) | B (n = 25) | C (n = 25) | 6 Months | 12 Months | |||||

| A vs B | A vs C | B vs C | A vs B | A vs C | B vs C | |||||||

| High-sensitivity C-reactive protein (mg/L) | 4.8 ± 4.1 | 3.2 ± 2.0 | 4.2 ± 2.6 | 4.8 ± 4.3 | 3.3 ± 1.8 | 3.7 ± 2.8 | 0.06 | 0.34 | 0.38 | 0.09 | 0.16 | 0.79 |

| p Value 0–6 months | 0.46 | 0.97 | 0.12 | |||||||||

| p Value 6–12 months | 0.91 | 0.53 | 0.24 | |||||||||

| p Value 0–12 months | 0.43 | 0.65 | 0.03 ⁎ , ↓26.0% ⁎ | |||||||||

| Tumor necrosis factor-α (pg/ml) | 12.1 ± 8.9 | 11.8 ± 10.4 | 15.2 ± 13.9 | 12.4 ± 8.9 | 12.7 ± 10.9 | 13.0 ± 12.9 | 0.91 | 0.34 | 0.29 | 0.93 | 0.86 | 0.92 |

| p Value 0–6 months | 0.37 | 0.40 | 0.43 | |||||||||

| p Value 6–12 months | 0.59 | 0.26 | 0.00 ⁎ , ↓14.5% ⁎ | |||||||||

| p Value 0–12 months | 0.78 | 0.53 | 0.01 ⁎ , ↓19.8% ⁎ | |||||||||

| Adiponectin (µg/ml) | 14.62 ± 8.2 | 15.6 ± 5.7 | 16.8 ± 9.1 | 14.4 ± 7.8 | 15.2 ± 5.3 | 16.4 ± 8.9 | 0.29 | 0.34 | 0.91 | 0.28 | 0.36 | 0.86 |

| p Value 0–6 months | 0.67 | 0.37 | 0.03 ⁎ , ↑9.1% ⁎ | |||||||||

| p Value 6–12 months | 0.48 | 0.42 | 0.38 | |||||||||

| p Value 0–12 months | 0.83 | 0.56 | 0.07 | |||||||||

| Interleukin-6 (pg/ml) | 1.7 ± 1.3 | 1.6 ± 1.4 | 1.8 ± 1.3 | 1.8 ± 1.5 | 1.6 ± 1.5 | 1.8 ± 1.4 | 0.67 | 0.89 | 0.59 | 0.55 | 0.91 | 0.64 |

| p Value 0–6 months | 0.32 | 0.79 | 0.39 | |||||||||

| p Value 6–12 months | 0.42 | 0.98 | 0.93 | |||||||||

| p Value 0–12 months | 0.04 ⁎ , ↑11.4% ⁎ | 0.58 | 0.56 | |||||||||

| Interleukin-10 (pg/ml) | 9.4 ± 6.6 | 10.1 ± 6.5 | 10.6 ± 8.1 | 8.7 ± 6.5 | 9.8 ± 5.9 | 11.5 ± 8.4 | 0.61 | 0.45 | 0.17 | 0.68 | 0.15 | 0.04 ⁎ |

| p Value 0–6 months | 0.20 | 0.74 | 0.00 ⁎ , ↑10.4% ⁎ | |||||||||

| p Value 6–12 months | 0.01 ⁎ , ↓7.4% ⁎ | 0.20 | 0.00 ⁎ , ↑8.5% ⁎ | |||||||||

| p Value 0–12 months | 0.01 ⁎ , ↓11.2% ⁎ | 0.78 | 0.00 ⁎ , ↑19.8% ⁎ | |||||||||

| Interleukin-6/interleukin-10 | 0.31 ± 0.04 | 0.21 ± 0.23 | 0.21 ± 0.26 | 0.37 ± 0.49 | 0.21 ± 0.25 | 0.19 ± 0.25 | 0.38 | 0.16 | 0.49 | 0.43 | 0.20 | 0.51 |

| p Value 0–6 months | 0.07 | 0.59 | 0.06 | |||||||||

| p Value 6–12 months | 0.24 | 0.86 | 0.07 | |||||||||

| p Value 0–12 months | 0.07 | 0.58 | 0.04 ⁎ , ↓24% ⁎ | |||||||||

| Interleukin-18 (pg/ml) | 250 ± 154 | 251 ± 161 | 187 ± 126 | 244 ± 127 | 249 ± 148 | 168 ± 89 | 1.00 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.96 | 0.18 | 0.17 |

| p Value 0–6 months | 0.17 | 0.18 | 0.77 | |||||||||

| p Value 6–12 months | 0.67 | 0.90 | 0.21 | |||||||||

| p Value 0–12 months | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.14 | |||||||||

| Soluble intercellular adhesion molecule type 1 (ng/ml) | 363 ± 80 | 342 ± 96 | 333 ± 83 | 374 ± 69 | 342 ± 110 | 323 ± 71 | 0.38 | 0.23 | 0.72 | 0.19 | 0.04 ⁎ | 0.46 |

| p Value 0–6 months | 0.96 | 0.15 | 0.23 | |||||||||

| p Value 6–12 months | 0.39 | 0.98 | 0.19 | |||||||||

| p Value 0–12 months | 0.62 | 0.55 | 0.06 | |||||||||

| Plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1 (ng/ml) | 18.8 ± 6.9 | 17.9 ± 8.4 | 16.4 ± 7.5 | 17.9 ± 5.9 | 15.5 ± 8.7 | 13.9 ± 5.8 | 0.67 | 0.28 | 0.50 | 0.21 | 0.04 ⁎ | 0.42 |

| p Value 0–6 months | 0.30 | 0.48 | 0.86 | |||||||||

| p Value 6–12 months | 0.31 | 0.05 | 0.01 ⁎ , ↓15.2% ⁎ | |||||||||

| p value 0–12 months | 0.54 | 0.27 | 0.03 ⁎ , ↓16.8% ⁎ | |||||||||

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree