Fig. 9.1.

Natural history of Barrett’s oesophagus.

Risk factors: Chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD; worse with nocturnal symptoms), risk factors for GERD (age, male, obesity, caffeine, alcohol, tobacco and spicy, fatty and acidic foods, visceral fat, Caucasian)

Prevalence: 2 % in Western countries; 6–12 % of all patients undergoing oesophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) [1]

Classification

Short-segment Barrett’s: ≤3 cm

Long-segment Barrett’s: >3 cm; higher risk of dysplasia and cancer [2]

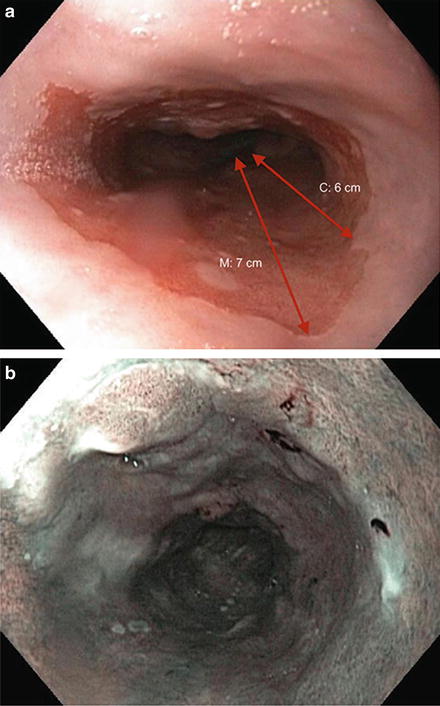

Prague Classification of Barrett’s (endoscopic grading) [3]:

C: Circumferential extent in cm

M: Maximum extent in cm

For example, patient with 7 cm length of columnar lined mucosa with intestinal metaplasia proximal to the gastric folds, 4 cm of which is 100 % circumferential, and 3 additional cm of non-circumferential “islands” or “tongues” of Barrett’s is represented as C4M7.

Pathophysiology

Pathophysiology remains unclear; however acid, bile and other reflux-related products seem to play a role

40-fold increased risk of oesophageal and GEJ adenocarcinomas [4]

0.33–0.5 %/year from non-dysplastic Barrett’s to adenocarcinoma; 0.9 %/year to high-grade dysplasia

Correlates with Barrett’s length (0.2 %/year for short segment)

25-fold increase in mortality from oesophageal cancer compared to general population

Dysplasia

Low-grade dysplasia (LGD) increases the risk of progression to high-grade dysplasia (HGD) and adenocarcinoma

HGD is a red flag for the development, or occult presence, of adenocarcinoma

Many harbor synchronous occult adenocarcinoma

45–60 % develop adenocarcinoma within 5 years (5 % are > T1a) [5]

Clinical Presentation

Most patients are asymptomatic or manifest GERD symptoms

Heartburn, regurgitation, acid taste in the mouth, belching, indigestion

Atypical GERD or laryngopharyngeal reflux disease symptoms may also be present.

Persistent throat clearing, persistent cough, globus sensation, hoarseness, chocking episodes

Work-Up

EGD may suggest Barrett’s with segments of salmon-colored columnar like mucosa in the lower oesophagus (Fig. 9.2).

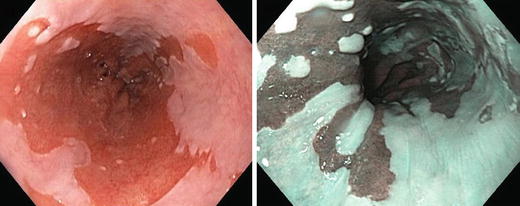

Fig. 9.2.

Barrett’s oesophagus is seen on oesophagogastroscopy as salmon-coloured mucosa extending from the gastroesophageal junction.

Graded according to Prague criteria [3]

New endoscopic imaging adjuncts to increase sensitivity of targeted biopsies: chromoendoscopy, narrow-band imaging, autofluorescence, confocal microscopy.

Management: (Fig. 9.3)

Fig. 9.3.

Management algorithm for Barrett’s oesophagus. *: High-grade dysplasia should be treated either endoscopically or surgically based on several factors: patient compliance for future endoscopic surveillance, focal vs. multifocal lesions, tortuous oesophagus, grade of differentiation and lymphovascular invasion if patient has associated invasive malignancy.

Medical

Acid-suppressive therapy (proton-pump inhibitors): symptom control

Regression of Barrett’s: 7 %; progression of Barrett’s: 41 % [6]

Use of anti-inflammatory cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitors as chemoprevention is controversial

Endoscopic

The choice of intervention is based on site, extent, histology and pre-malignant potential of the lesion (Table 9.1).

Table 9.1.

Comparison of various treatment modalities for Barrett’s oesophagus.

Procedure

Advantages

Disadvantages

Endoscopic

Ablative therapy

• Minimally invasive

• Ablation up to SM1

• Proven efficacy of eradication of dysplasia

• Operator dependant and costly

• Small risk of strictures/perforation

• Requires close follow-up and repeat endoscopies

Endoscopic mucosal resection

• Minimally invasive

• Resection up to muscularis mucosa

• Can be used for early localized cancer

• Provides pathological specimen details

• Can only resect up to 0.5–1 cm at one time (piece-meal resection for larger lesions)

• High rate of strictures for long-segment circumferential resections

• Risk of perforation

• Requires close follow-up and repeat endoscopies

• Risk of missing metachronous lesions

• Operator dependant and costly

• High risk (30 %) of local recurrence when used for early-stage oesophageal cancer [26]

Combined ablation/EMR

• Decreased recurrence rate compared to EMR alone

• Risk of perforation

• Requires close follow-up and repeat endoscopies

• Operator dependant and costly

Endoscopic submucosal dissection

• Minimally invasive

• Resection up to SM2/3

• High rates of R0 resection

• Can be used for early localized malignant lesions

• Limited experience

• Technically challenging

• Risk of perforation

Surgical

Anti-reflux surgery

• Treats the underlying cause

• Possible regression of metaplasia

• May facilitate subsequent ablative therapies

• Not proven definitively in preventing cancer in patients with Barrett’s

• May make future surveillance difficult/inadequate

Oesophagectomy

• Complete resection of diseased oesophagus

• Provides pathological specimen details (grade, LVI, stage)

• High rates of morbidity and mortality

Ablative therapies: Radiofrequency ablation (RFA), photodynamic therapy, argon plasma coagulation (APC), cryotherapy, laser ablation, multipolar electrocoagulation (MPEC)

Goal: Ablate metaplastic mucosa, with subsequent re-epithelialization with normal squamous mucosa

RFA preferred due to its limited risks, consistent therapeutic depth, ease of use and proven efficacy of eradication of disease [7]

APC and MPEC: Not as effective, greater risk of strictures and buried glands

Most ablative therapies have an efficacy of Barrett’s eradication of approximately 80–85 %. Less effective for ultra-long segments (>8 cm), tortuous oesophagus and large hiatal hernias.

Due to high cost, usually reserved for patients with dysplastic Barrett’s

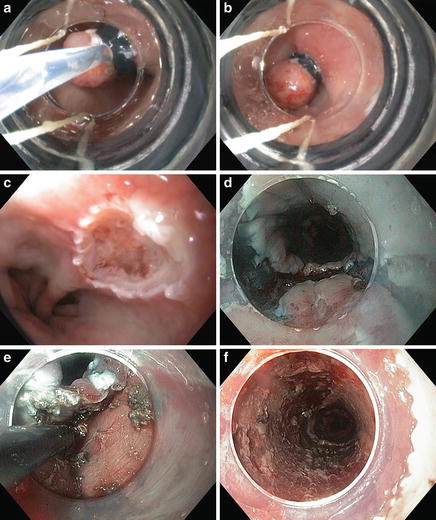

Resective therapies (Fig. 9.4)

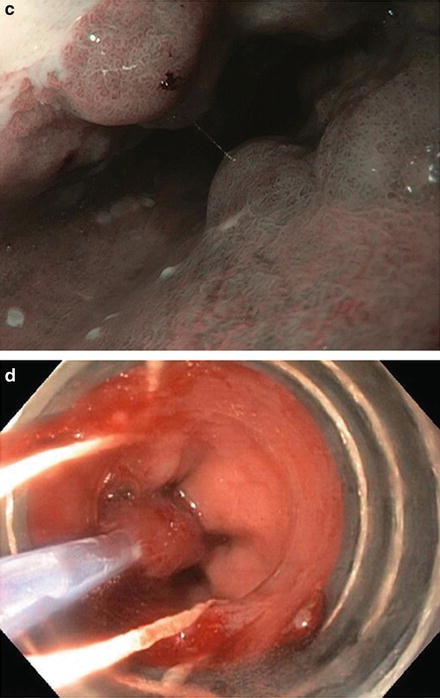

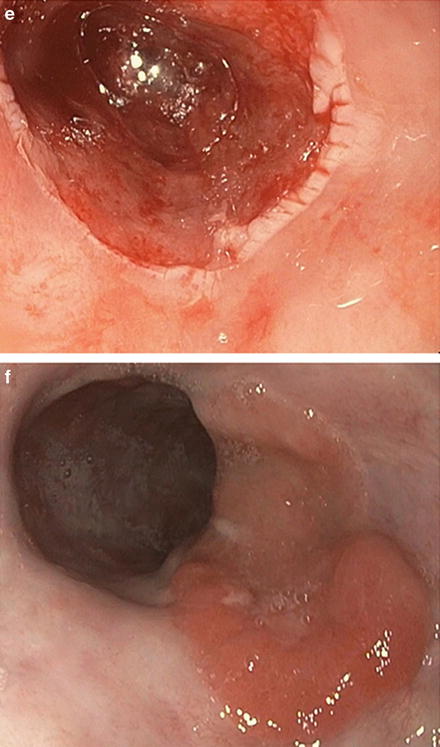

Fig. 9.4.

Endoscopic resections include EMR (a–c) and ESD (d–f) for a patient with pT1aNx, moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma and no lymphovascular invasion.

Endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR)

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD)

Ablative and endoscopic resection therapies are frequently used together (Fig. 9.5)

Fig. 9.5.

The Prague classification is an endoscopic grading system that takes into account circumferential extent (C) and maximum extent (M). (a) This patient has multinodular Barrett’s oesophagus C6M7. b–c: The extent of Barrett’s can also be seen on narrow-band imaging.

Endoscopic resection (EMR or ESD) is required to diagnose and possibly treat early cancers associated with Barrett’s oesophagus

This should be done for all nodular/irregular Barrett’s mucosa prior to any ablative treatment

Increases the diagnostic accuracy for occult cancer, and may be adequate oncologic treatment if an early cancer is identified

Surgery

Anti-reflux surgery—controversial

Regression of Barrett’s: 25 %; progression of Barrett’s: 9 % [6]

Does not eliminate the risk of dysplasia and cancer

Laparoscopic anti-reflux surgery may be required prior to ablation of dysplastic Barrett’s in some cases:

Large hiatal hernias with tortuous oesophagus

Ongoing oesophagitis despite maximal medical therapy

Oesophagectomy

Reserved for HGD that is not amenable to endoscopic therapies

Laparoscopic oesophagectomy is the approach of choice

Oesophageal Cancer

Overview

Incidence:

Canada: 1,700 estimated new cases per year (nearly equivalent mortality rate)

USA: 18,000 estimated new cases per year (>15,000 estimated deaths) [8]

Squamous-cell carcinoma (SCC) predominates worldwide, while in North America, adenocarcinoma represents the majority of malignancies of the oesophagus (>75 %), given the increasing incidence of Barrett’s oesophagus

SCC: Mostly upper and middle-third oesophagus

Adenocarcinoma: Mostly middle and distal-third oesophagus and gastroesophageal junction

Other histologic subtypes: Neuroendocrine tumour, gastrointestinal stromal tumour, adeno-squamous carcinoma, melanoma, sarcoma, lymphoma

Risk factors:

SCC: Geographic location (some areas of the world are endemic), smoking, alcohol, head and neck malignancy, achalasia, caustic injury, diverticular disease, Plummer-Vinson syndrome, radiation therapy, tylosis, nitrosamines and other nitrosyl compounds

Adenocarcinoma: Barrett’s oesophagus, GERD, obesity, smoking

Clinical Presentation

Most patients do not become symptomatic until late in the course of illness.

Obstructive symptoms: Progressive dysphagia (solid food, then liquids), regurgitation, oesophageal perforation, chronic cough, aspiration

Hematemesis, melena

Symptoms of local invasion: Hoarseness, bronchoespohgeal fistula, empyema.

Systemic symptoms: Weight loss, fatigue

Physical examination may reveal cervical or supraclavicular lymph nodes

Work-Up and Staging (Table 9.2)

Table 9.2.

TNM staging classification for oesophageal cancer.

Primary tumour (T) | |||||

T1 | Invasion of lamina propria, muscularis mucosae, submucosa | ||||

T1a | Invasion of lamina propria, muscularis mucosae | ||||

T1b | Invasion of submucosa | ||||

T2 | Invasion of muscularis propria | ||||

T3 | Invasion of adventitia | ||||

T4a | Invasion of pleura, pericardium or diaphragm | ||||

T4b | Invasion of other adjacent structures (e.g. aorta, vertebral body, trachea) | ||||

Regional lymph nodes (N) | |||||

N0 | No regional lymph node metastases | ||||

N1 | 1–2 regional lymph nodes | ||||

N2 | 3–6 regional lymph nodes | ||||

N3 | >6 regional lymph nodes | ||||

Distant metastasis (M) | |||||

M0 | No distant metastasis | ||||

M1 | Distant metastasis | ||||

Squamous-cell carcinoma | |||||

Stage | T | N | M | Grade | Tumour location |

IA | T1 | N0 | M0 | 1 | Any |

IB | T1 | N0 | M0 | 2,3 | Any |

T2–3 | N0 | M0 | 1 | Lower | |

IIA | T2–3 | N0 | M0 | 1 | Upper, middle |

T2–3 | N0 | M0 | 2,3 | Lower | |

IIB | T2–3 | N0 | M0 | 2,3 | Upper, middle |

T1–2 | N1 | M0 | Any | Any | |

IIIA | T1–T2 | N2 | M0 | Any | Any |

T3 | N1 | M0 | Any | Any | |

T4a | N0 | M0 | Any | Any | |

IIIB | T3 | N2 | M0 | Any | Any |

IIIC | T4a | N1, N2 | M0 | Any | Any |

T4b | Any N | M0 | Any | Any | |

Any T | N3 | M0 | Any | Any | |

IV | Any T | Any N | M1 | Any | Any |

Adenocarcinoma | |||||

Stage | T | N | M | Grade | Tumour location |

IA | T1 | N0 | M0 | 1,2 | Any |

IB | T1 | N0 | M0 | 3 | Any |

T2 | N0 | M0 | 1,2 | Any | |

IIA | T2 | N0 | M0 | 3 | Any |

IIB | T3 | N0 | M0 | Any | Any |

T1–2 | N1 | M0 | Any | Any | |

IIIA | T1–T2 | N2 | M0 | Any | Any |

T3 | N1 | M0 | Any | Any | |

T4a | N0 | M0 | Any | Any | |

IIIB | T3 | N2 | M0 | Any | Any

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|