generally produce serious upper extremity symptoms by embolization to the digital arteries (Table 14.2). Occlusive disease of the subclavian artery, although very common, is rarely a cause of limb-threatening upper extremity ischemia unless complicated by embolization to the forearm, palmar, or digital arteries.

FIGURE 14.1. Raynaud’s attack in a 47-year-old woman shows various stages of pallor, cyanosis, and rubor. |

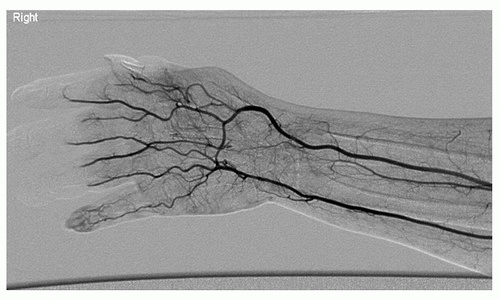

proximal ulnar/radial arterial occlusive disease, respectively. If the blood pressure difference is more than 15 mm Hg between adjacent levels, or between the radial and ulnar arteries, it is likely due to a stenosis or occlusion (Fig. 14.4).

TABLE 14.1 DISEASES ASSOCIATED WITH INTRINSIC DIGITAL ARTERY OCCLUSIONS | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree