8 Non-Neoplastic Pathology of the Large and Small Airways

The Conducting Airways

The trachea and conducting airways play a vital role in lung function. The diseases that affect these structures are commonly related to inhalation exposure but also may arise from developmental anomalies and systemic diseases (Box 8-1). In this section, topics are presented in anatomic order, beginning with the trachea and proceeding distally to the bronchi and bronchioles.

The Trachea

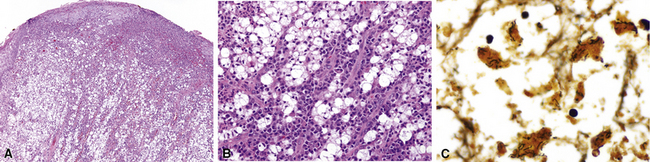

Non-neoplastic pathology of the trachea can be divided broadly into extrinsic and intrinsic diseases. Among extrinsic diseases are certain infections, such as rhinoscleroma (caused by Klebsiella rhinoscleromatis1,2) (Fig. 8-1), and systemic autoimmune diseases that affect cartilage (e.g., Wegener granulomatosis3,4). These diseases may cause tracheal obstruction or collapse and may also involve the larynx or the conducting airways, or both. Diseases intrinsic and unique to the trachea are few and mainly of congenital and/or metabolic origin. In the following section, we will describe three of these entities: tracheal amyloidosis, tracheobronchomalacia, and tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica. The latter may be rare but deserves mention as it can be encountered incidentally during bronchoscopy.

Tracheal Amyloidosis

Tracheobronchial amyloidosis is an idiopathic disease characterized by amyloid deposition, often throughout the tracheobronchial tree5,6 but sometimes restricted to the larynx and trachea.7 Approximately 150 cases have been reported in the literature. Tracheobronchial amyloidosis most frequently produces dyspnea, wheezing (sometimes misdiagnosed as asthma), recurrent pneumonia, and atelectasis, which are believed to be sequelae of the narrowed airways. Pulmonary function tests usually show fixed obstruction. On histopathologic examination, amyloid deposits usually are seen in the submucosa and may involve the entire tracheal or bronchial wall, occurring in irregular masses or sheets (Fig. 8-2). Amyloid may be accompanied by multinucleate giant cells; calcification and ossification are frequent5,6,8,9 (Fig. 8-3). When amyloid is identified in bronchoscopic biopsy specimens, this typically is an organ-limited manifestation, similar to nodular lung parenchymal amyloid.10 Of the three major types of amyloid, AL, AA, and transthyretin, the AL type is the most common in tracheobronchial amyloid deposits. The prognosis is poor: Nearly one third of patients die within 7 to 12 years of diagnosis.6 Therapy is limited to debulking procedures and stent placement for localized lesions, although some evidence suggests that radiation therapy may provide more definitive treatment.11–14

Tracheobronchomalacia

Tracheobronchomalacia (TBM) is a term used to encompass a number of conditions characterized by a decrease in the structural rigidity of the trachea and conducting airways. Such changes are manifested clinically by excessive expiratory collapse of the central airways owing to increased flaccidity or redundancy of the posterior membranous airway wall, or to weakness of the supporting cartilage (a recent in-depth review of the disease is available15). Although typically a disease process of the central airways, TBM has been shown to frequently have associated air trapping on computed tomography (CT) scan, an indicator of small-airway disease.16,17

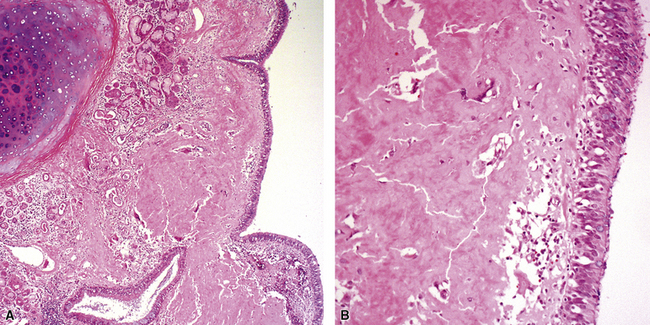

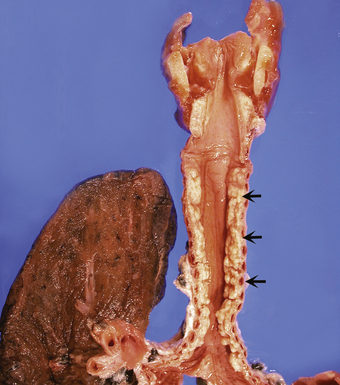

Both children and adults may be affected.18 In children, the disease most often is related to prematurity and the requirement for prolonged mechanical ventilation. In these patients, TBM appears to be self-limited.19,20 In adults, TBM is seen in the middle-aged and the elderly and is a progressive condition, commonly seen in association with COPD.16 Other reported associations in adults include prolonged intubation, vascular anomalies, and exposure to mustard gas.21 TBM may complicate amyloidosis and rheumatoid arthritis when these diseases affect the airways22 and may be related to relapsing polychondritis, a systemic disease affecting the cartilaginous tissue in several organs, including the airways.18,23–25 Pathologically, the tracheal wall is soft, as a result of inflammatory destruction of the cartilage (Fig. 8-4). Over time, the cartilage is replaced by fibrous tissue, accompanied by inflammatory infitration and reparative vascular proliferation.

Treatment is variable and depends on symptom severity, with conservative therapy appropriate for mildly symptomatic cases and more invasive therapy indicated for severely symptomatic cases, including tracheoplasty (for reduction of expiratory tracheal collapse and symptomatic improvement).26 In the absence of treatment, severely symptomatic TBM can lead to significant respiratory morbidity and rarely may be fatal.

Tracheobronchopathia Osteochondroplastica

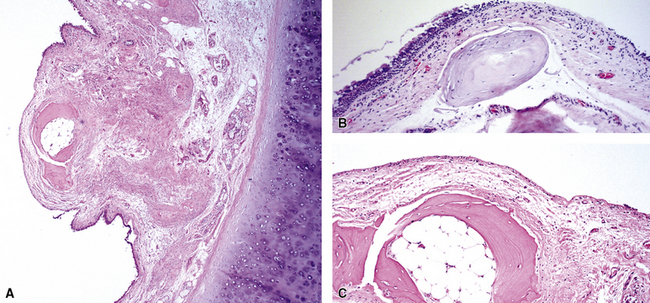

Tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica is a rare lung disease characterized by the presence of cartilaginous or osseous submucosal nodules that bulge into the lumen of the trachea and bronchi (Fig. 8-5), with sparing of the posterior membranous portion.27–30 The etiology and pathogenesis are unknown. The disease affects adults more commonly than children, with a predilection for males. Most cases are asymptomatic, and are most often diagnosed incidentally during intubation or bronchoscopy. A minority of patients may experience cough, dyspnea, and hemoptysis.

The bronchoscopic appearance alone is usually diagnostic, and biopsy is seldom if ever required.31 In the rare bronchoscopic biopsy showing the cartilaginous or ossified lesions of tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica (Fig. 8-6), the differential diagnosis includes ossified amyloid deposits. Other conditions associated with endoluminal nodular lesions include endobronchial sarcoidosis, endobronchial granulomatous infections, papillomatosis, and tracheobronchial calcinosis.

The Bronchi

The conducting airways begin at the carina and extend distally in the lung to the level of the noncartilaginous bronchioles. Although many diffuse lung diseases may involve the large airways secondarily, some primary diseases also may affect the bronchi and are presented here. Asthma-associated diseases, typically observed in the large airways, are discussed later in the final section of this chapter. Cystic fibrosis and ciliary disorders are not discussed here, because detailed expositions can be found in other sources.32,33

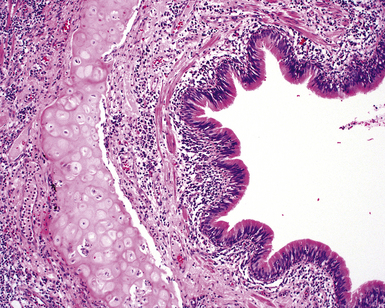

Bronchitis

Infectious and inflammatory conditions of the large airways are particularly relevant to the surgical pathologist and the cytopathologist, given the prominence of inflammatory manifestations seen in biopsies obtained through the bronchoscope (endobronchial and transbronchial specimens). In practice, the presence of acute or chronic inflammation in endobronchial biopsies, in which bronchial mucosa and muscle or cartilage are evident, demands a descriptive diagnosis (Fig. 8-7). It is best to avoid the use of the term “chronic bronchitis” in reference to such inflammatory changes involving respiratory mucosa, because it carries a clinical implication regarding the diffuse nature of the disease and specific clinical manifestations. When bronchitis occurs as a direct result of respiratory infection, necrosis of the mucosa may be present (acute necrotizing bronchitis). In the postinfection period, residual chronic inflammatory changes may be the dominant findings. Unfortunately, the list of possible etiologic disorders associated with chronic inflammation in bronchial mucosa is quite long (Box 8-2) and sufficiently diverse as to not be useful in narrowing the scope of the clinical differential diagnosis. For this reason, a careful search for other, more specific findings is always in order, and these are worth mentioning as a list of pertinent negative findings (e.g., vasculitis, granulomas, necrosis, tumor).

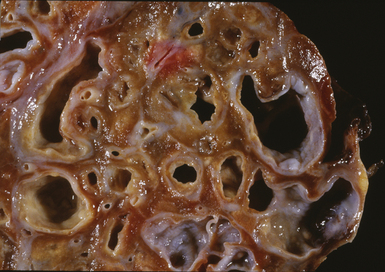

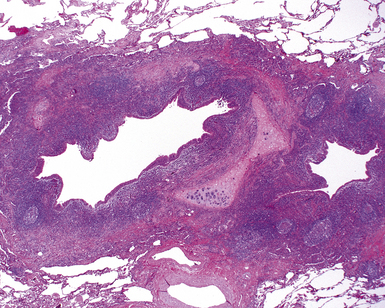

Bronchiectasis

Bronchiectasis is defined as a permanent dilatation of the cartilaginous airways (bronchi), often attended by acute and chronic inflammation. Conceptually, bronchiectasis can be considered the end result of any number of conditions that damage the airway wall and result in weakening over time and dilatation.34 Primary causes are most commonly related to inherited abnormalities (ciliary dysfunction, abnormal mucus production), whereas secondary causes are numerous. In a review of multiple published series of bronchiectasis between 1935 and 1981, Barker and Bardana35 found a significant proportion of idiopathic cases (as much as 30% according to Nicotra and associates36). Among recognizable causes of bronchiectasis are infections, primary ciliary dyskinesia, immunodeficiency, cystic fibrosis, rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease,37 and graft-versus-host disease.38 An intriguing implication of Helicobacter pylori in the pathogenesis of bronchiectasis has been raised in some studies.39–41 In specific conditions such as cystic fibrosis, bronchiectasis may dominate the pulmonary pathology. Bronchiectasis, outside the setting of cystic fibrosis, often is perceived to be rare in Western societies but remains an important cause of chronic suppurative lung disease in the developing world. The decline in hospital admission rates for pediatric bronchiectasis in the Western countries has been noted since the 1950s and has been attributed to improvements in sanitation and nutrition, introduction of childhood immunization (particularly against pertussis and measles), and the early and frequent use of antibiotics.

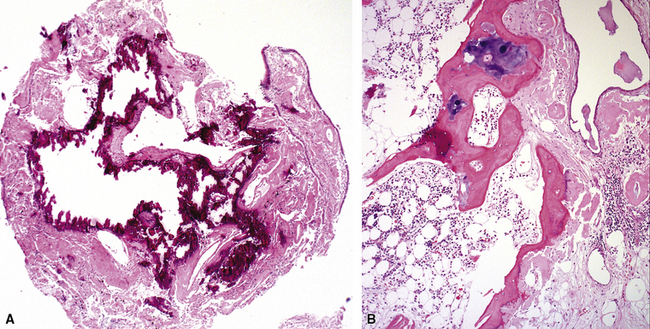

Bronchiectasis is a radiologic diagnosis in the living patient but has distinctive features in resected lungs (Fig. 8-8) and lobes and sometimes in surgical biopsies. The proposed historical classification of bronchiectasis divided the process into three types:

Presenting signs and symptoms include cough with production of purulent sputum, fever, shortness of breath, and, occasionally, hemoptysis. No age or sex predilection has been noted, and the disease tends to run a course of recurrent exacerbation, sometimes with superimposed infection. Inflammatory changes in biopsies obtained with the bronchoscope correlate poorly with the presence or absence of bronchiectasis. Nevertheless, such specimens may be useful for ancillary laboratory studies (such as ultrastructural studies in search of ciliary abnormalities). On plain films of the chest, classic parallel linear opacities (referred to as “tram tracks”) correspond to thickened bronchial walls, whereas tubular opacities reflect mucus-filled bronchi. Today, most cases of bronchiectasis are diagnosed by HRCT.42,43 Overall, the sensitivity of HRCT in detecting bronchiectasis is quite high.44,45 The HRCT findings in bronchiectasis are summarized in Box 8-3.

Box 8-3 High-Resolution Computed Tomography Findings in Bronchiectasis

The gross findings in bronchiectasis have been well described in autopsy series.46 For the histopathologist, acute and chronic inflammatory changes dominate the bronchoscopic biopsy picture (Fig. 8-9). The presence of necrotic debris and mucus in airways may be a sign of coexistent bronchiectasis, but in most instances, even surgical lung biopsy findings only reflect “downstream” secondary manifestations of obstruction or infection occurring more proximally. Lymphoid hyperplasia surrounding the large airways may occur in bronchiectasis and bronchoscopically derived biopsies may sample such hyperplastic lymphoid tissue, raising concern for tumor on occasion (especially when a portion of a germinal center dominates the small biopsy specimen). Caution is always advisable in these settings to avoid the overdiagnosis of lymphoproliferative disease. Also, the necrotic granular debris that may accompany bronchiectasis may be sampled by bronchoscopic biopsy, thereby raising concern for necrotic neoplasm or abscess. Providing a broad differential diagnosis is the best approach here, to avoid confusion and possible misdirection of clinical management.

Middle Lobe Syndrome

The concept of “right middle lobe syndrome” was highlighted in studies of children with chronic failure to thrive and right middle lobe abnormalities on chest radiographs. The proposed hypothesis was based on the notion that lymphoid hyperplasia occurring around the right middle lobe bronchus produced compression and narrowing of the bronchial lumen. Also, the position of the middle lobe (and the lingula of the left lung) relative to the remainder of the tracheobronchial tree makes it susceptible to obstruction and secondary chronic inflammatory changes in the lobe (long narrow bronchus). In clinical practice, the disease occurs more frequently in adults and often without an identifiable obstructing lesion.47 This population consists predominantly of middle-aged or elderly women, and the condition has been referred to as “Lady Windermere syndrome.”48–50 A role for Mycobacterium avium complex infection has been postulated in the pathogenesis of middle lobe syndrome, although it remains unclear whether this is an epiphenomenon related to the common occurrence of bronchiectasis in this condition. Consolidation of the right middle lobe, or lingula, attended by bronchiectasis, is typical.34,47

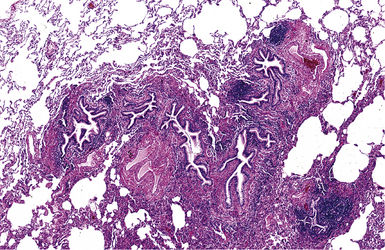

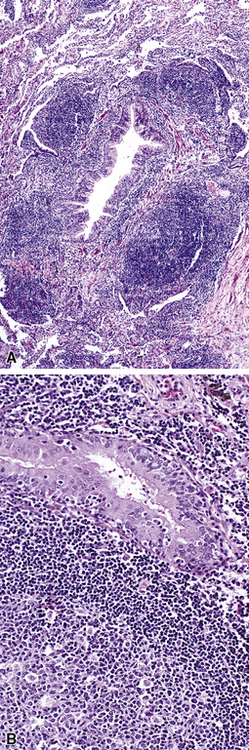

In surgical lung biopsies of the right middle lobe or lingula, advanced remodeling, granulomatous inflammation, extensive inflammatory infiltrates, and mucostasis, when present together, should always suggest the possibility of middle lobe syndrome (Fig. 8-10). The presence of granulomas in the context of middle lobe syndrome should raise suspicion for colonization by atypical mycobacterial species, and acid-fast organisms may be identified in granulomas.48 A number of inflammatory changes are observed in middle lobe syndrome, and these are listed in Box 8-4.47,51 Removal of any obstructing lesions, whether neoplasm or other, in early stages of the disease process may avoid the need for lobectomy.52

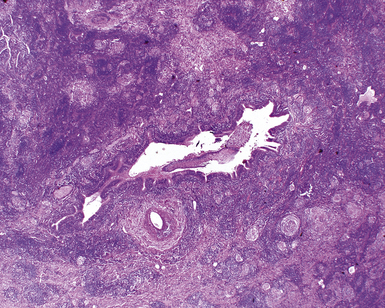

Figure 8-10 Middle lobe syndrome. The bronchial wall shows prominent lymphoid infiltration, with many germinal centers.

The Small Airways (Bronchioles and Alveolar Ducts)

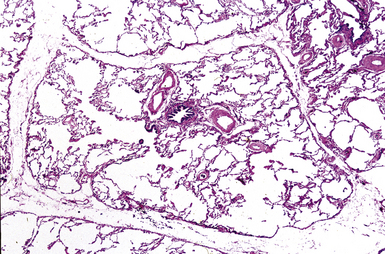

The small airways of the lung include the small bronchi, with a diameter less than 2 to 3 mm, and the membranous bronchioles (terminal and respiratory bronchioles). Terminal bronchioles have a diameter of less than 1 mm and are just proximal to the respiratory bronchioles, the first airways that have alveoli budding from their walls. The terminal bronchioles are located in the center of the pulmonary lobule and, like all conducting airways, are always accompanied by a pulmonary artery branch (Fig. 8-11). In cross-sectional views, their respective diameters are approximately equal (Fig. 8-12A). The lumen of the terminal bronchiole is uniform in longitudinal histologic sections, but minor variations in size can be seen (see Fig. 8-12B).

It is said that the small airways constitute the “Achilles heel” of the lung, because they play an important role in air distribution and flow but lack the rigid structure of the bronchi to protect them from collapse during exhalation, especially when affected by disease. The small airways can be affected secondarily by inflammatory diseases that involve primarily the bronchi or the alveoli, or both, or by primary diseases that selectively involve these delicate anatomic structures. No single classification of bronchiolar disorders has been widely accepted, although any number of classification schemes have been proposed based on cause and underlying diseases, radiologic features, histopathologic findings, or some combination of these parameters.53–56 As recently proposed by Ryu and colleagues, bronchiolar disorders can be divided into three groups: primary bronchiolar disorders, bronchiolar involvement in interstitial lung diseases, and bronchiolar involvement in large airway disease57,58 (Box 8-5). From a histopathologic point of view it should be pointed out that patients rarely come to lung biopsy with a preoperative diagnosis of “small airway disease.” The reasons for this are legion but mainly reflect the fact that disorders of the small airways are relatively “silent” clinically and radiologically. In addition, some of the small- airway lesions are quite subtle histologically and, at first glance, may be overlooked.59,60

Box 8-5 Classification of Bronchiolar Disorders

Adapted from Ryu JH. Classification and approach to bronchiolar diseases. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2006;12(2):145–151; and Ryu JH, Myers JL, Swensen SJ. Bronchiolar disorders. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168(11):1277–1292.

It is the rare lung biopsy that does not show some degree of histopathologic alteration in the small airways. Critical to the evaluation of such changes is knowledge of the clinical manifestations, the radiologic distribution of disease (whether localized or bilateral and diffuse), and the patient’s cigarette smoking history. Attempts to predict clinical disease based on isolated abnormalities of the small airways, as viewed through the microscope, often are unrewarding. The HRCT scan may provide valuable information regarding the possible pathologic pattern of disease, as shown in Table 8-1.

Table 8-1 High-Resolution Computed Tomography Abnormalities of the Small Airways

| Radiologic Finding | Pathologic Pattern |

|---|---|

| Centrilobular nodularity | Cellular bronchiolitis |

| Follicular bronchiolitis | |

| Respiratory bronchiolitis | |

| Peribronchial nodules | Follicular bronchiolitis |

| “Tree in bud” pattern | Cellular bronchiolitis |

| Panbronchiolitis | |

| Diffuse or “geographic” air-trapping | |

| Mosaic pattern | Constrictive bronchiolitis |

| Bronchioloectasis, bronchiectasis | Panbronchiolitis |

| Patchy ground-glass attenuation | Respiratory bronchiolitis |

| Ground-glass opacity | Follicular bronchiolitis |

Modified from Lynch DA. Imaging of small airways diseases. Clin Chest Med. 1993;14(4): 623–634.

Inflammatory Bronchiolitis

Inflammatory bronchiolitis, also known as cellular bronchiolitis, is a generic term that includes acute bronchiolitis, chronic bronchiolitis, and combined forms with variable amounts of both types of processes. All forms may be associated with bronchiolar fibrosis.60 An important point is that both acute and chronic forms of bronchiolitis may have significant overlap, with one form typically being dominant. Diseases of the airways rarely have histopathologic features sufficiently specific to point to a single etiologic disorder or a specific disease in the absence of some characteristic finding (e.g., viral inclusions, aspirated foreign material). When the surgical pathologist is confronted with isolated inflammatory changes in the small airways, it is important to invoke a differential diagnosis to stimulate clinicopathologic correlation, and thereby help to narrow considerations in the clinical differential diagnosis.

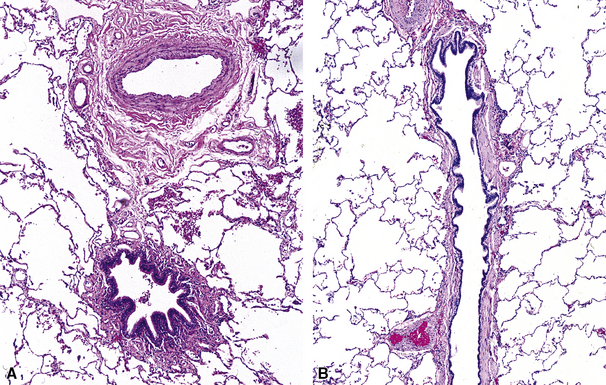

Acute Bronchiolitis

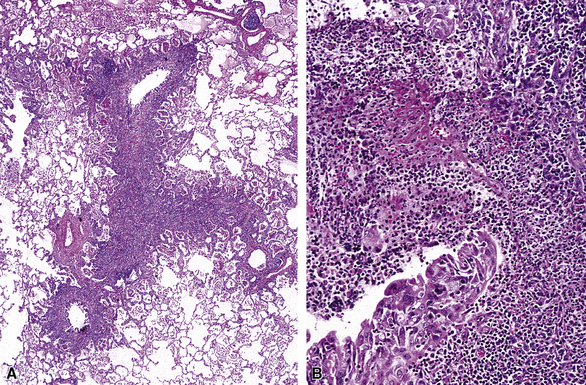

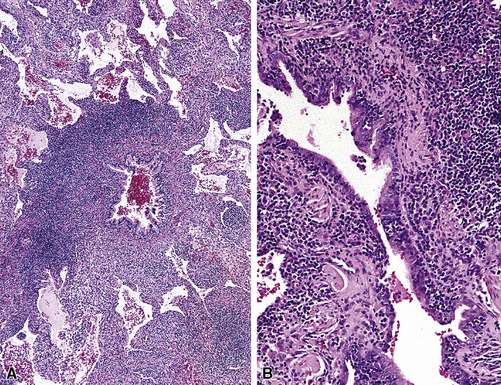

Florid acute bronchiolitis is characterized by predominantly acute inflammation of the small airways, with variable epithelial sloughing. Extension of acute inflammation into surrounding peribronchiolar parenchyma is typical (Fig. 8-13). Very often, acute bronchiolitis is associated with some degree of chronic inflammatory infiltration, as described below. Conditions associated with relatively pure acute bronchiolitis include the early phase of certain infections (most of which also produce epithelial necrosis).61,62 A careful search for viral inclusions is especially relevant in this scenario. Acute fume or toxic gas inhalation can also produce acute small-airway injury, with few if any chronic changes. Loose connective tissue polyps may develop as a consequence of basement membrane disruption with fibroblastic migration into the airway lumens from subepithelial regions (so-called Masson polyps). Acute aspiration can manifest occasionally as acute bronchiolitis (most commonly seen at autopsy, in cases in which aspiration may have been part of the terminal event). Acute bronchiolitis can be an uncommon manifestation of Wegener granulomatosis.63

Acute and Chronic Bronchiolitis

Acute and chronic inflammation of the small airways (Fig. 8-14) is one of the most common manifestations of so-called cellular bronchiolitis.64 This inflammatory process frequently is associated with other bronchiolocentric manifestations, including intraluminal polyp formation, constriction and obliteration, and presence of lymphoid follicles within the peribronchiolar sheath (follicular bronchiolitis).

When acute and chronic bronchiolitis are the primary manifestation in the lung biopsy, clinical manifestations may be accompanied by completely obstructive, completely restrictive, or a mixture of obstructive and restrictive pulmonary physiology. HRCT scans may show a predominantly nodular pattern, although reticulonodular infiltrates are more commonly observed. Box 8-6 lists the most frequent diseases associated with acute and chronic bronchiolitis.

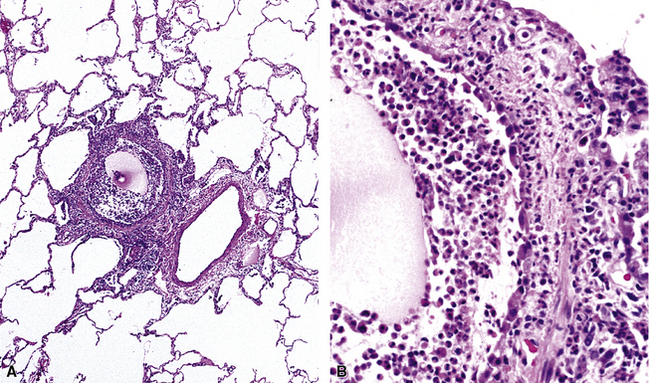

Chronic Bronchiolitis

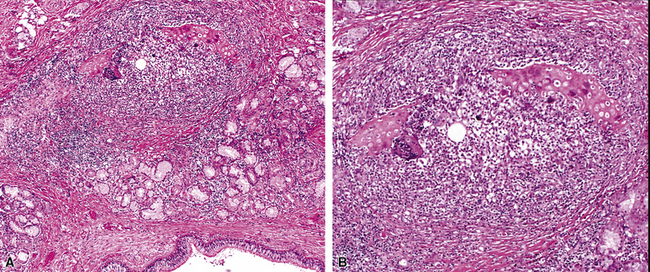

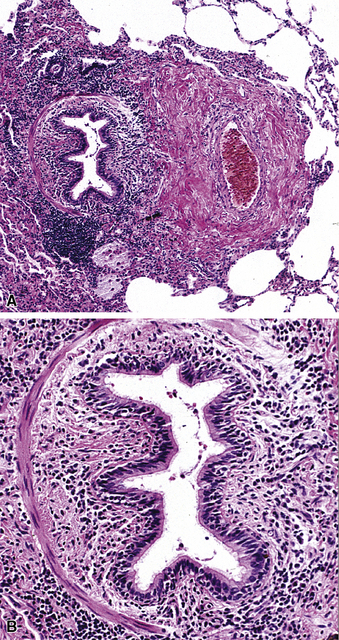

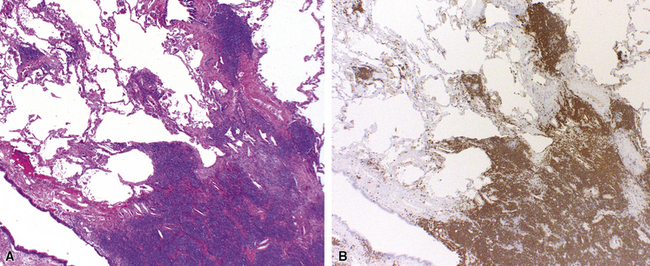

Chronic inflammation within and surrounding the walls of small airways (Figs. 8-15 and 8-16) can be seen in several conditions (Box 8-7). Chronic bronchiolitis can occur with or without lymphoid follicles or some degree of fibrosis. Follicular bronchiolitis is a specific subtype of chronic bronchiolitis, characterized by the presence of lymphoid follicles with well-formed germinal centers surrounding the bronchiolar walls, sometimes with lymphocytes migrating in the respiratory epithelium, either singly or in small clusters (Figs. 8-17 to 8-19). Follicular bronchiolitis may be seen in several connective tissue diseases.65–69 In cases with dense and extensive lymphoid infiltrates, especially if lymphoepithelial lesions are prominent, one should always consider the possibility of a lung lymphoma, most of which are low-grade B cell lymphomas of extranodal marginal zone type, arising from the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT)70–72 (Fig. 8-20). Follicular bronchiolitis may also be seen in some occupational exposure settings, such as nylon flocking workers,73–77 and in immunodeficiency syndromes including the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) related to human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.78

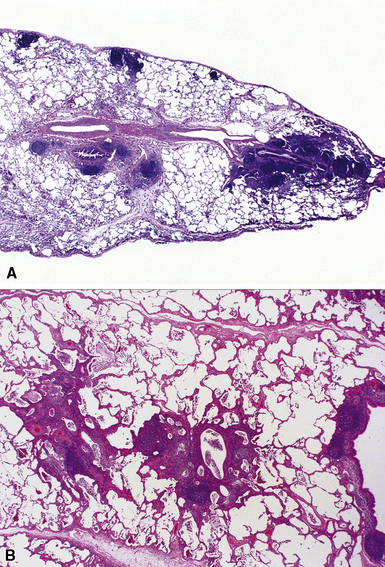

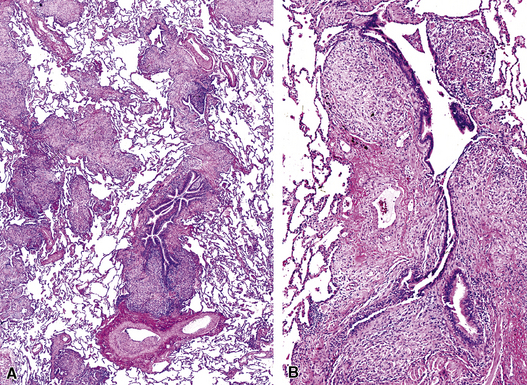

Granulomatous Bronchiolitis

Isolated granulomatous bronchiolitis is unusual. Sarcoidosis is the leading consideration in the differential diagnosis in the absence of necrosis (Fig. 8-21). Granulomas of sarcoidosis are usually distributed along the lymphatic routes in the lung and therefore are frequently bronchiolocentric, allowing bronchoscopic biopsy to provide excellent diagnostic material. On the other hand, when necrosis is present, granulomas are usually present in the surrounding lung parenchyma as well, and herald the strong possibility of infection (especially infection caused by mycobacteria and fungi)79 (Fig. 8-22). Necrotizing granulomatous bronchiolitis also may be seen in the setting of middle lobe syndrome47 and chronic necrotizing forms of pulmonary aspergillosis.80 Even in the absence of necrosis, however, infection should still remain high in the differential diagnosis. Non-necrotizing granulomatous bronchiolitis can be seen in association with inflammatory bowel disease, such as Crohn disease, sometimes accompanied by microabscesses.81 Non-necrotizing peribronchiolar granulomas are also seen in a majority of patients with hypersensitivity pneumonitis (Fig. 8-23). Generally, granulomas in hypersensitivity are less well delimited and well formed than in infectious diseases and may take the form of loose aggregations of histiocytic epithelioid cells, with or without giant cells.