Primary vasculitis

Large-sized vessel vasculitis

Takayasu’s arteritis

Giant cell (temporal) arteritis

Medium-sized vessel vasculitis

Polyarteritis nodosa

Kawasaki disease

Primary granulomatous central nervous system vasculitis

Small-sized vessel vasculitis

Antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody

Wegener granulomatosis

Churg-Strauss syndrome

Microscopic polyangiitis

Immune complex small-sized vessel vasculitis

Henoch-Schönlein purpura

Cryoglobulinemic vasculitis

Secondary vasculitis

Connective tissue diseases

Systemic lupus erythematosus

Rheumatoid arthritis

Sjögren syndrome

Behçet syndrome

Infectious diseases

Bacteria

Virus

Drugs

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

Anticancer drugs

Antibiotics

Paraneoplastic vasculitis

Carcinoma

Lymphoproliferative neoplasm

Myeloproliferative neoplasm

Clinical Features

The diagnosis of the several GI vasculitides is often built on the correlation of clinical manifestations, image and laboratory findings, and histopathological features. As the clinical or image findings may not be distinct from diseases that can mimic systemic vasculitis (Table 10.2) and therefore may have limited value in making a specific diagnosis, a high suspicion rate is needed [7]. Nevertheless, the possibility of vasculitis must be considered whenever mesenteric ischemic changes develop in a young patient; are noted in atypical sites such as stomach, duodenum, or rectum; appear simultaneously in the large and small intestine; or are associated with genitourinary involvement [1, 2]. As suggested by Ha and colleagues, knowledge of systemic clinical manifestations in affected patients may suggest a specific diagnosis [8] (Table 10.3).

Table 10.2

Diseases that can mimic systemic vasculitis

Systemic multisystem disease | |

Infection | Subacute bacterial endocarditis |

Neisseria | |

Rickettsia | |

Metastatic carcinoma | |

Malignancy | |

Paraneoplastic | |

Other | Sweet syndrome |

Scurvy | |

Cocaine abuse | |

Occlusive vasculopathy | |

Embolic | Cholesterol crystals |

Atrial myxoma | |

Infection | |

Thrombotic | Antiphospholipid syndrome |

Procoagulant states | |

Calciphylaxis | |

Others | Ergot |

Radiation | |

Köhlmeier-Degos | |

Angiographic | |

Aneurysmal | Fibromuscular dysplasia |

Neurofibromatosis | |

Occlusion | Coarctation |

Atherosclerosis | |

Table 10.3

Systemic manifestations of vasculitis

% | |

|---|---|

Fever | 66 |

Peripheral nervous system involvement | 61 |

Weight loss | 60 |

Arthralgia | 52 |

Cutaneous symptoms | 44 |

Renal involvement | 37 |

Myalgia | 34 |

Hypertension | 23 |

Lung involvement | 19 |

Central nervous system involvement | 13 |

Asthma | 13 |

Ear, nose, and throat involvement | 13 |

Cardiac involvement | 10 |

Ophthalmologic involvement | 10 |

Raynaud syndrome/digital ischemia | 8 |

The signs and symptoms of GI involvement in systemic vasculitis depend upon the size and location of the affected vessel. As a result, in the large-sized vessel diseases, abdominal manifestations may be indistinguishable from those of atherosclerotic or embolic mesenteric ischemia, except for evidences of systemic disease. In the medium-sized arteries, such as the CT and SMA, inflammation can lead to aneurysm formation (Fig. 10.1), as noticed in polyarteritis nodosa (PAN). Rupture of aneurysms may cause intra-abdominal or GI hemorrhage. In small-artery involvement, ulceration and stricture formation are common and can complicate with perforation.

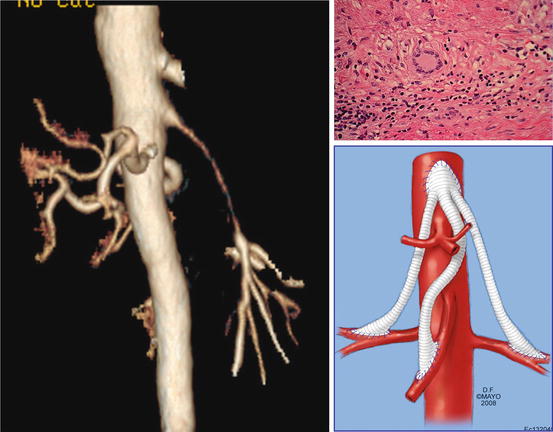

Fig. 10.1

Multiple intrahepatic aneurysms in a patient with polyarteritis nodosa who presented with ruptured intrahepatic artery aneurysm (By permission of Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. All rights reserved)

The GI symptoms demonstrate a wide spectrum, ranging from mild transient abdominal pain to life-threatening complications requiring emergency surgery, such as bowel perforation, peritonitis, or hypovolemic shock (Table 10.4).

Table 10.4

Gastrointestinal manifestations and radiologic findings

Abdominal findings in mesenteric vasculitis | |

|---|---|

% | |

Abdominal pain | 97 |

Nausea or vomiting | 34 |

Diarrhea | 27 |

Hematochezia or melena | 16 |

Hematemesis | 6 |

Esophageal ulcerations | 11 |

Gastroduodenal ulcers | 27 |

Colorectal ulcerations | 10 |

Gastritis | 6 |

Peritonitis | 18 |

Bowel perforations | 15 |

Intestinal occlusion | 6 |

GI ischemia/infarction | 16 |

Appendicitis | 10 |

Cholecystitis | 8 |

Acute pancreatitis | 5 |

Abnormal angiography | 67 |

Abnormal abdominal CT | 75 |

Surgical abdomen | 34 |

The GI tract may be involved in vasculitides in up to 50 % of the cases [9]. However, the majority of patients are asymptomatic. Rits and colleagues in a retrospective review of the Mayo Clinic patients who underwent mesenteric revascularization due to mesenteric vasculitis evidenced 7,514 patients evaluated for vasculitis in a 24-year period, 102 (0.013 %) had symptoms of mesenteric ischemia, and only 15 underwent open or endovascular treatment for mesenteric vasculitis [1]. Pagnoux et al. reviewing 344 patients with systemic vasculitides in a 21-year period have evidenced 62 (0.18 %) patients with associated GI symptoms [3].

Abdominal pain is the most frequent and almost constant finding in these cases, occurring in 97 % of the patients. The intensity of the pain varies widely and usually does not lie in a specific location in the abdomen. Patients with GI vasculitis may also present chronic abdominal pain after eating, named intestinal angina, similar to patients with chronic atherosclerotic occlusion of the intestinal vessels. This symptom generally is followed by weight loss and cachexia and may be misdiagnosed as cancer. The pain can also be similar to the findings of acute mesenteric ischemia, which is out-of-proportion pain on the abdominal exam. However, a surgical abdomen was not systematically associated with intense abdominal pain or tenderness. Nausea and vomiting are present in one-third of the patients, and 27 % had diarrhea. Ischemic hepatitis, gastritis, esophagitis, pancreatitis, cholecystitis, and appendicitis were also reported in those patients [10–13]. Symptomatic patients may present with bleeding from gastrointestinal mucosal erosions or small aneurysms of the distal mesenteric or hepatic artery branches.

Image Findings

Duplex Ultrasound

Duplex ultrasound is an accurate screening test for ostial arterial lesions. A peak systolic velocity greater than 275 cm/s and an end-diastolic velocity greater than 45 cm/s seems to be highly specific for significant superior mesenteric artery (SMA) stenosis [14]. Moreover, patients with Behçet syndrome and GI involvement had increased flow in both the superior and inferior mesenteric arteries. These findings were not similar in patients with Behçet syndrome and no GI involvement. Altered pericolic fat may suggest presence of transmural necrosis [15, 16]. However, since the duplex scan has limitations, such as patients presenting with abdominal distention or intraperitoneal gas, and is operator-dependent, these findings may not be always reliable, and a second study with axial images of the abdomen is often necessary, in order to exclude other causes of pain and for analysis of the anatomy and planning of the procedure.

Endoscopy and Colonoscopy

Endoscopy and colonoscopy are useful exams in cases where symptoms of upper or lower GI involvement are suspected, proceeding with biopsy if ulceration is present. Despite the few reports on the subject, the combination of the tests and radiographic findings facilitates the precise diagnosis of the vasculitis [17]. Ischemic enteritis may suggest Kawasaki’s disease, granulomatous enteritis can be present in Wegener granulomatosis, and mucosal edema and hemorrhage at the bowel may suggest systemic lupus erythematous or Churg-Strauss disease. During these procedures, the manipulation of the endoscopic device, the bowel insufflation, and biopsies must be performed with extreme caution and finesse, in order to prevent bowel perforation.

Computed Tomography

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) may provide useful information on inflammatory, neoplastic, and vascular diseases of the abdomen and have the advantage of assessment of emergent abdominal vascular conditions, ischemic bowel disease, and its complications. Bowel wall thickening, a “target sign,” an increased attenuation of mesenteric fat, increased or delayed enhancement in the bowel wall due to hyperemia, or frank bowel infarction or perforation with pneumatosis intestinalis, portal venous air, or pneumoperitoneum are suggestive of acute ischemia.

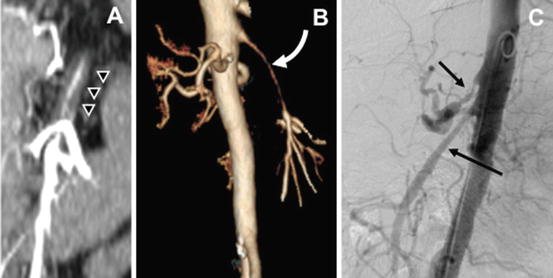

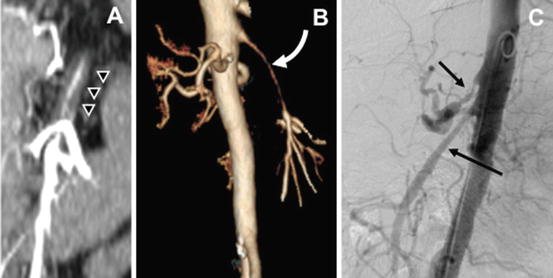

Arterial-phase CT scans and particularly CT angiography (CTA) are of great value in the evaluation of mesenteric arteries. Arterial wall thickening is a characteristic finding in patients with mesenteric vasculitis (Fig. 10.2). They help to identify site, level, and cause of bowel ischemia. In addition, venous phases may identify the mesenteric veins and the bowel wall itself, improving accuracy in the identification of bowel perforation and abscess [2, 8]. Limitations of the study are dye allergy and renal failure.

Fig. 10.2

Computed tomography angiography in a patient with mesenteric vasculitis. Coronal view demonstrates thickening of the arterial wall (a) also noticed in 3-D reconstruction (b). Angiography shows smooth lesion (c) sparing the origin of the mesenteric vessels

Angiography

Angiography remains the “gold standard” test for diagnosis of peripheral vessel splanchnic disease, particularly visceral aneurysms in polyarteritis nodosa and arterial narrowing in Takayasu’s disease. Its role as confirmatory test and for planning revascularization diminished, in favor of the noninvasive modalities previously discussed. More frequently, angiography is obtained in conjunction with a planned endovascular intervention. Exceptions are patients with suboptimal imaging studies and those with extensive calcification, small vessels, or multiple prior stents causing metallic artifact.

Specific Disorders in Mesenteric Vasculitis

Although the ischemic symptoms and image findings may be similar regardless of the systemic vasculitis, distinct outcomes may result; hence specific syndromes deserve mention.

Takayasu’s Arteritis

Takayasu’s Arteritis (pulseless disease) is a large-sized vessel granulomatous vasculitis characterized by ocular disturbances and marked pulse weakening in the upper and lower extremities. It is related to fibrous thickening of the aortic arch with narrowing or obliteration of the ostia of the great vessels in the arch. TA involves the aortic arch, and in 32 % of the cases, it affects the rest of the aorta and its branches. Generalized symptoms and signs include malaise, fever, night sweats, arthralgia, and weight loss. GI symptoms are mainly nonspecific, such as anorexia, nausea, vomiting, and loss of weight, and start during the pulseless phase of the disease. GI morbidity is due to arterial stenosis; however, organ ischemia is rare. Chronic mesenteric ischemia has already been reported and is manifested similar to atherosclerotic presentation. Diagnosis is suspected by duplex scan and confirmed by arteriography or CTA. The findings consist in irregular thickening of the aortic wall with intimal wrinkling, stenosis, poststenotic dilatation, aneurysm formation, and occlusion with subsequent luxurious collateral circulation [2, 4, 8, 18].

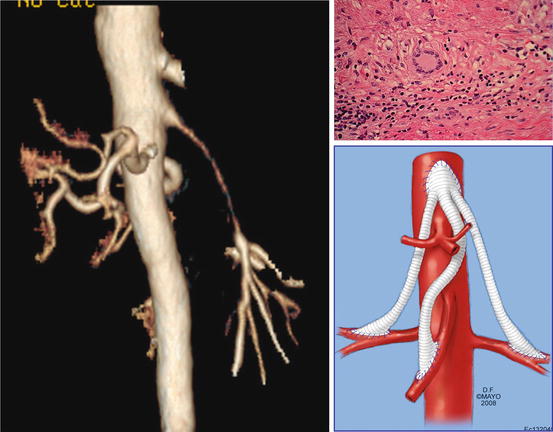

Giant Cell Arteritis

Giant cell arteritis (GCA) is one of the most common vasculitides to present with occlusive mesenteric artery disease (Fig. 10.3). Giant cell arteritis is also known as temporal arteritis, cranial arteritis, or Horton disease. It most commonly involves large- and medium-sized arteries. Its original description affects branches of the external carotid artery and can lead to permanent blindness if not recognized and treated with corticosteroids. The name (giant cell arteritis) reflects the type of inflammatory cell involved and seen on a biopsy. The terms “giant cell arteritis” and “temporal arteritis” are sometimes used interchangeably, because of the frequent involvement of the temporal artery. However, it can involve other large vessels, such as the aorta (“giant cell aortitis”) and its branches.

Fig. 10.3

Patient with long segment superior mesenteric narrowing and bilateral renal artery disease due to giant cell arteritis. Biopsy of arterial wall demonstrates giant cell (By permission of Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. All rights reserved)

Polyarteritis Nodosa

Polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) is a fibrinoid necrotizing vasculitis that involves small- and medium-sized arteries. Multiple aneurysm formation (Fig. 10.1) is the characteristic finding of the disease and is present in 50–60 % of the patients [8]. The kidney is the most commonly involved organ (80–90 % of cases), followed by the gastrointestinal tract (50–70 %), liver (50–60 %), spleen (45 %), and pancreas (25–35 %). GI involvement increases mortality rates, due to the extensive destruction of the mesenteric arteries. The small intestine is the most commonly affected territory of the GI tract, followed by the mesentery and colon. Approximately two-thirds of patients have abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. Other gastrointestinal signs and symptoms include peritonitis, mesenteric infarction, acute cholecystitis, appendicitis, and duodenal ulcers. In association with organ damage due to ischemia and infarction, GI hemorrhage occurs in 6 % of cases, bowel perforation in 5 %, and bowel infarction in 1.4 % of the cases [1, 3, 4, 7, 8, 19, 20].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree