Infections:

Virus: adenovirus, enterovirus (Coxsackie), echovirus, herpes simplex virus, hepatitis C virus, human immunodeficiency virus, parvovirus B19

Bacteria: Staphylococcus, Streptoccocus sp., Legionella, Mycobacterium sp., Mycoplasma pneumoniae

Fungi: Aspergillus, Candida, Cryptococcus

Protozoa: Trypanosoma cruzi, Toxoplasma gondii

Rickettsias: Coxiella burnetti, Rickettsia typhi

Immunological syndromes:

Churg-Strauss syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease, giant cell myocarditis, hypereosinophilic syndrome, Wegener’s granulomatosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, sarcoidosis

Hypersensitivity reactions:

Penicillin, ampicillin, cephalosporins, tetracyclines, digoxin, tricyclic antidepressants, diuretics, clozapine

Venoms from scorpion or viper

Toxic reactions to therapeutic and illicit drugs:

Cocaine, amphetamines, anthracyclines, phenytoin, ethanol

Remarks |

In the majority of cases diagnosed at autopsy, it is not possible to identify the pathogen and myocarditis is attributed to viral infection |

Endomyocardial biopsy has low sensitivity since inflammation is usually patchy |

Young adults constitute the age group more commonly affected |

Myocarditis is a significant cause of sudden death in infants and children |

The inflammatory process, which occurs during infections, can be produced by direct pathogen invasion, toxin production or through immunological mediators. Medication can induce myocardial damage either directly by a toxic effect or can be mediated by hypersensitivity reactions.

Symptomatology in the majority of patients involves dyspnoea, chest pain or palpitations, and can be part of the following clinical entities:

Associated with pericarditis.

Recently diagnosed heart failure.

Acute coronary syndrome without coronary artery disease.

Syncope and ventricular arrhythmias.

Dilated cardiomyopathy with chronic heart failure.

To confirm a diagnosis of myocarditis, it is necessary to analyse the cardiac tissue. The Dallas criteria were proposed in 1987 and provided a histopathological categorization by which the diagnosis of myocarditis could be established from endomyocardial biopsies. According to these criteria, myocarditis requires an interstitial inflammatory infiltrate and associated myocyte necrosis and/or degeneration. When these criteria are applied, a diagnosis of myocarditis is established in 25 % of the biopsied patients, or in up to two thirds of patients if more than five samples are taken. This low sensitivity is due to the fact that the inflammatory involvement is often patchy and can be missed, and also due to technical limitations. Currently, an endomyocardial biopsy is indicated in situations of a recently diagnosed heart failure (less than 3 months) with ventricular dysfunction that provokes a haemodynamic compromise or does not respond adequately to treatment. This biopsy should be carried out in experienced hospitals to avoid complications, which arise in around 1 % of the cases.

The wide spectrum of possible aetiologies, mechanisms of pathogenicity, variability of clinical presentation and the absence of a systematic histological examination, results in a poor understanding of the disease and limits progress in this field.

It is interesting to study the clinico-pathological correlation in the most frequent forms of myocarditis, which are the following:

Fulminant myocarditis: typically occurs 2 weeks after a viral infection. It manifests with a very severe decrease in cardiac function that threatens life, although a complete recovery is possible if the patient survives the acute period. Cardiac chambers appear with thickened walls, but are not dilated. Histology reveals abundant diffuse and active inflammatory infiltrates compatible with a diagnosis of myocarditis.

Acute myocarditis: Progression to heart failure is not as quick and serious as in fulminant myocarditis, although there is a greater risk of incomplete recovery of cardiac function. Myocardial tissue may show limited criteria for the diagnosis of myocarditis with few isolated foci of active inflammation.

Chronic active myocarditis: Clinical presentation is slower but clinical and histological recurrences are observed, with fibrosis and ventricular dysfunction in the medium-long term. Biopsy may show limited criteria for the diagnosis of myocarditis with few isolated foci of active inflammation.

Chronic persistent myocarditis: Biopsy may show limited criteria for the diagnosis of myocarditis with few isolated foci of active inflammation, but the patient suffers neither loss of cardiac function nor symptoms of heart failure.

Advances in several techniques have modified the perspectives of this disease and, undoubtedly, will improve its clinical approach:

The use of immunohistochemistry and molecular biology techniques (the viral genome has been isolated using the polymerase chain reaction) that allow the identification of viruses in the myocardium even in instances where the Dallas criteria are not met.

Cardiac Magnetic Resonance (CMR) provides accurate location and quantification of the inflammatory process, oedema and myocardial fibrosis. This imaging technique permits the identification of patients with myocarditis in up to 30 % of the cases that present with chest pain but without lesions in the coronary arteries. Currently, CMR is not as accessible as echocardiography; hence, it is not yet routinely used.

9.2 Lymphocytic Myocarditis

Lymphocytic myocarditis is caused mainly by viral infections. The most common viruses are enteroviruses, predominantly Coxsackie A and B. It is a common cause of sudden death in children and the young, accounting for 5–25 % of deaths depending on the series. In the cases of sudden death, patients usually reported a previous viral infection and it is not uncommon for sudden death to be the first clinical manifestation of myocarditis.

The heart may appear normal or dilated under gross examination. Occasionally, the heart has a more flaccid consistency and the appearance of the myocardium is patchy or mottled (Fig. 9.1a).

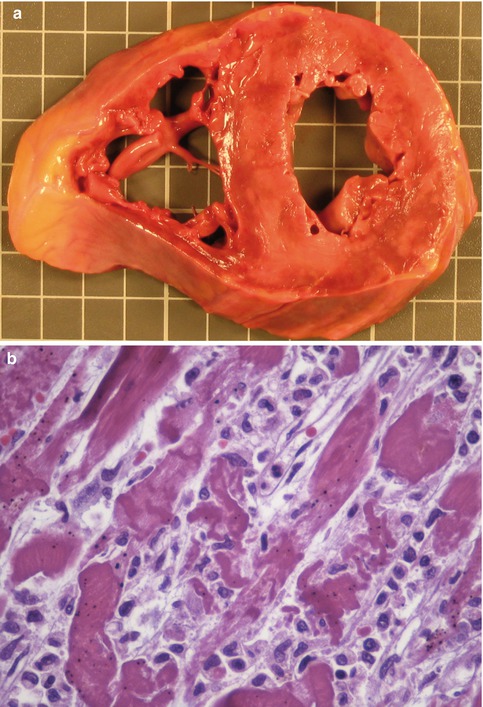

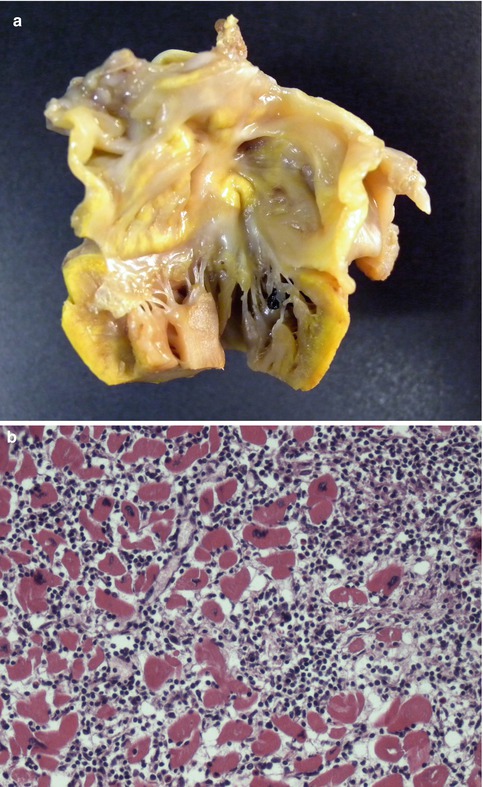

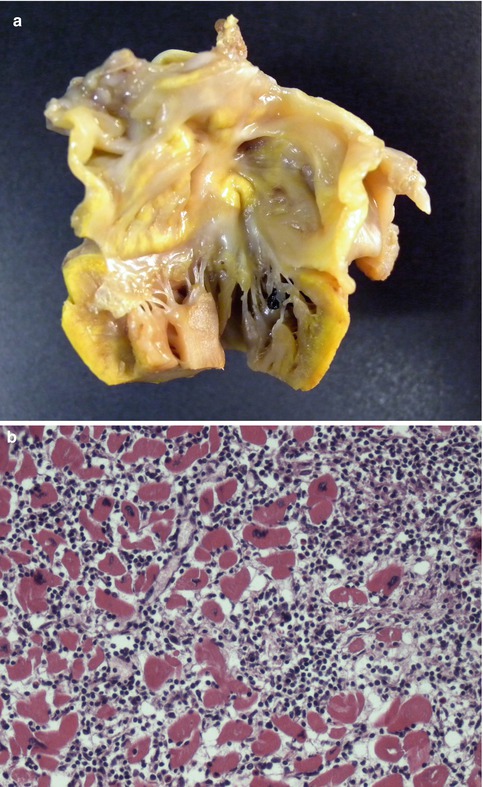

Fig. 9.1

A 24-year-old woman who died suddenly. (a) Transverse section of the heart in which the patchy appearance of the myocardium can be appreciated in the LV. (b) Histological image showing myocyte necrosis and inflammatory infiltrate, mainly composed of mononuclear cells (Lucena J, et al. (2007). Reproduced with permission from Cuadernos de Medicina Forense)

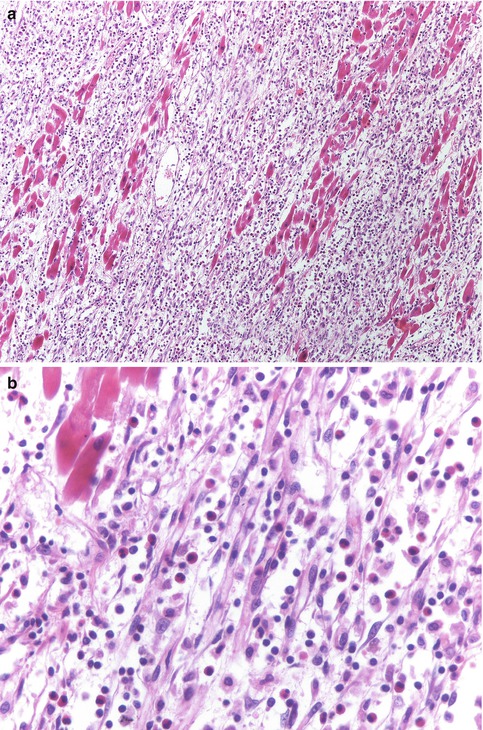

Lesions are usually focal, although sometimes there is a diffuse myocardial involvement. In acute viral myocarditis, histology shows myocyte necrosis, interstitial oedema and inflammatory infiltrates composed of mononuclear cells (mainly lymphocytes, with variable amounts of macrophages and plasma cells) (Fig. 9.1b). At autopsy, diffuse infiltrates can usually appear in several sections of the myocardium (Fig. 9.2), although sometimes the inflammatory involvement is more focal. In infantile acute viral myocarditis, in contrast to what occurs in other age groups, the inflammatory infiltration of neutrophils prevails, as in cases of widespread myocytic necrosis, although in the latter a polymorphic cellular infiltrate can be observed.

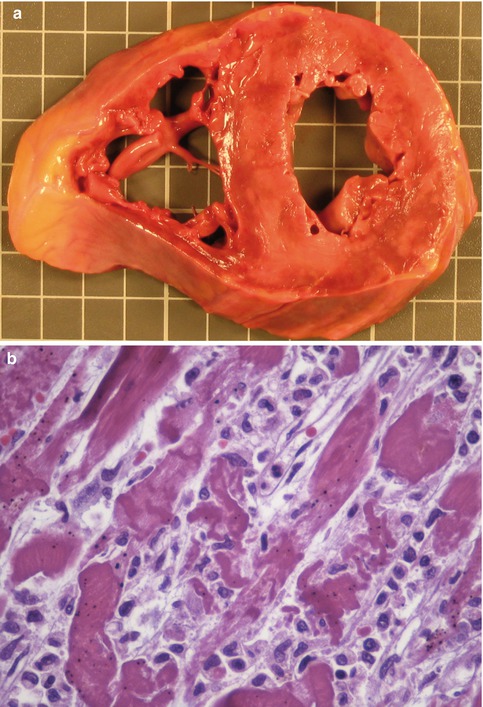

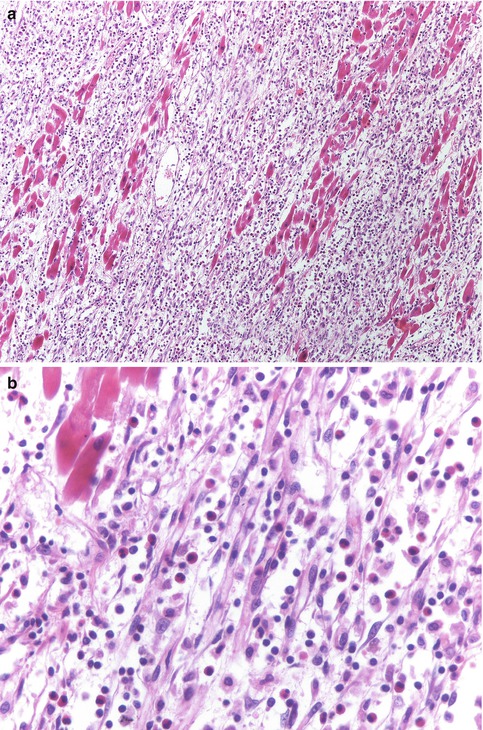

Fig. 9.2

Sudden death in a 21-year-old male, with no previous medical history, presenting symptoms of a viral syndrome 2 days before death. (a) Microscopic study revealed acute myocarditis with a widespread lymphocytic infiltrate and associated necrosis. (b, c) Detailed images showing focal myocyte necrosis and a mononuclear inflammatory cell infiltrate. PCR analysis from paraffin-embedded myocardial samples allowed the identification of Coxsackievirus B as the causal infectious agent

Newborn infants are at high risk of developing severe infections caused by enteroviruses, which can even be lethal. Neonatal enterovirus myocarditis is a rare but serious infection that usually manifests with signs and symptoms of congestive heart failure, and it is associated with high mortality. As previously discussed, in the early stages of the disease, the inflammatory infiltrate is mainly composed of polymorphonuclear leukocytes (neutrophils) (Fig. 9.3). In some instances, myocarditis can be fulminant with clinical features of congestive heart failure or cardiogenic shock that can result in death in less than 24 h (Fig. 9.4).

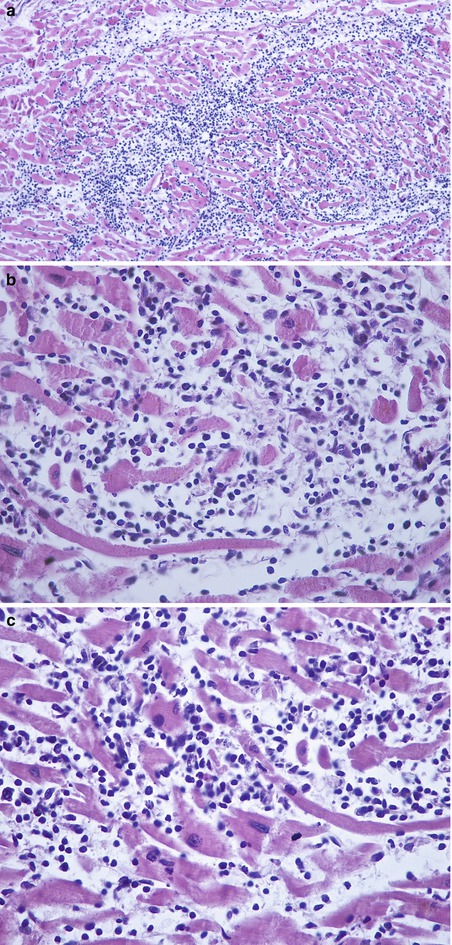

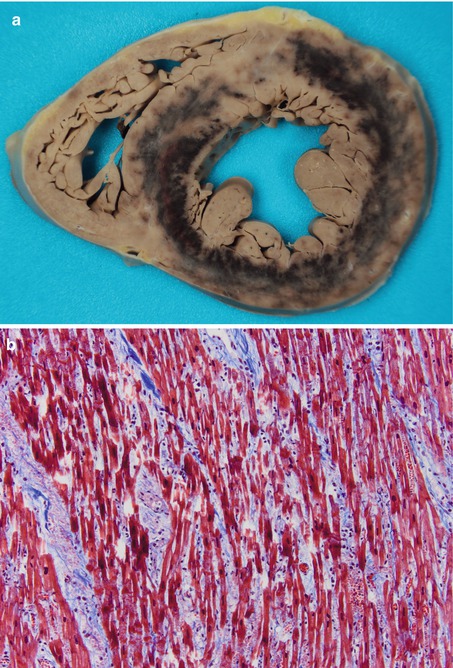

Fig. 9.3

Newborn-term infant with a normal neonatal period. Ten days after birth, the paediatrician observed hypotony, hepatomegaly and extreme bradycardia. He was taken to the casualty department, dying soon after. Necropsy studies showed acute myocarditis, more extended in the LV. (a) Gross examination of the heart showed a yellow-tan colour and necrotic appearance. (b) Photomicrograph showing a pleomorphic inflammatory infiltrate mainly composed of polymorphonuclear leukocytes, and widespread myocyte necrosis. Meningoencephalitis was also diagnosed. PCR determination identified presence of Coxsackievirus B in spleen and myocardial tissue samples taken at autopsy

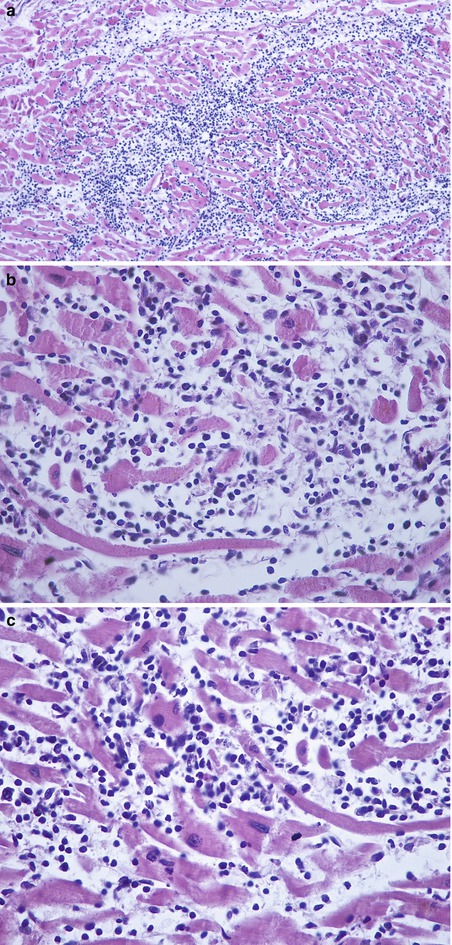

Fig. 9.4

A 6-year-old girl, with a recent episode of pharyngotonsillitis, who died in 10 h as a consequence of a cardiogenic shock with multiple organ failure. (a) Transverse section of the heart showing a diffuse patchy appearance of the LV myocardium, as well as marked circumferential haemorrhagic infiltration, probably due to the intensive treatment received. Microbiological analysis identified Influenza B virus, Parainfluenza virus type 4 and Rhinovirus in the pharyngeal exudate. (b) Microscopic image showing myocyte necrosis and inflammatory infiltrate, mainly lymphocytic, along with interstitial haemorrhage (Masson’s trichrome)

At post–mortem studies on persons who have died from natural or violent causes, it is not uncommon to find isolated foci of lymphocytic infiltrates in the interstitium, with minimal or absent myocyte necrosis or degeneration (Fig. 9.5). The significance of these foci of focal myocarditis is uncertain, although they could be a contributing factor to death in some cases. However, there is no consensus regarding the degree of extension of myocarditis required to justify death in the absence of other causes.

Fig. 9.5

Lymphocytic infiltrates in the interstitium were observed in the myocardium of a person who died in a traffic accident

The use of immunohistochemistry techniques (Fig. 9.6) has demonstrated that the majority of cells are T lymphocytes, while B lymphocytes and macrophages are present in lower numbers.

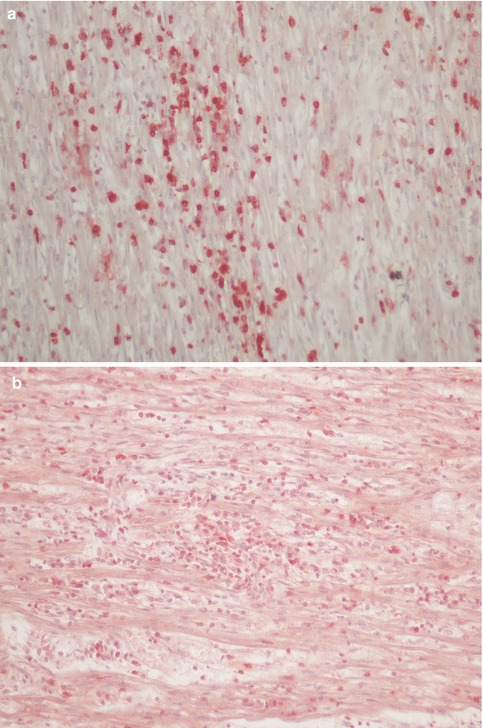

Fig. 9.6

A case of myocarditis showing inflammatory cells that stain positive for CD45 (common leukocyte antigen) (a) and CD3 immunostaining (T lymphocytes) (b)

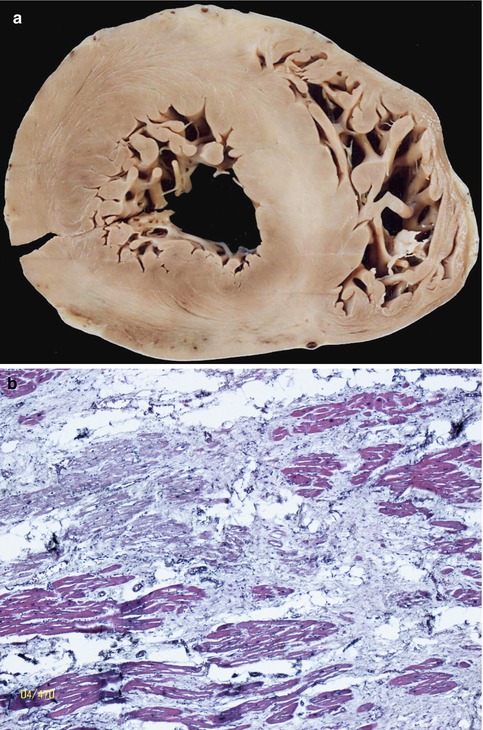

During the resolution period in lymphocytic myocarditis, necrotic myocytes are replaced with fibroblasts and collagen, which will finally create fibrous tissue, randomly distributed. Cases of sudden death have been reported in the subacute (Figs. 9.7 and 9.8) or the chronic (Figs. 9.9 and 9.10) phases, in which it is possible to find focal areas of necrosis and inflammation next to areas of replacement fibrosis (chronic myocarditis).

Fig. 9.7

Image shows a transmural involvement of the free wall of the LV with replacement fibrosis and mononuclear cell infiltration

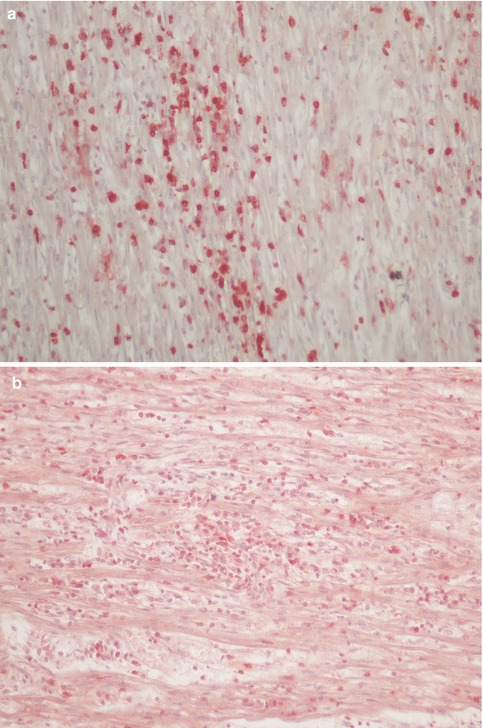

Fig. 9.8

Subacute myocarditis. (a) Replacement of necrotic myocytes with fibroblasts and lymphocytic infiltrate can be observed. (b) Image at higher magnification showing some eosinophils among the inflammatory infiltrate

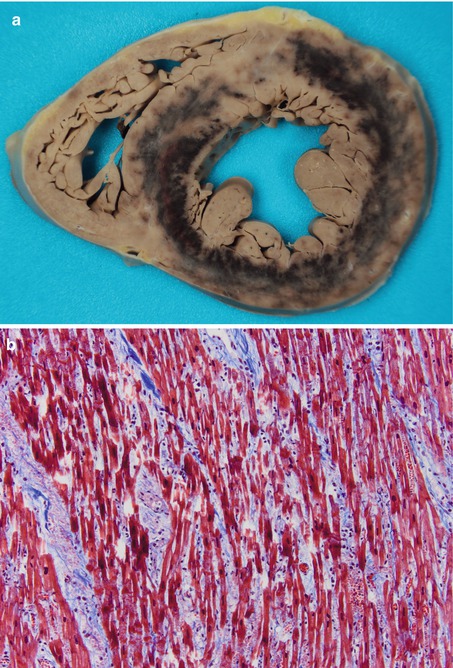

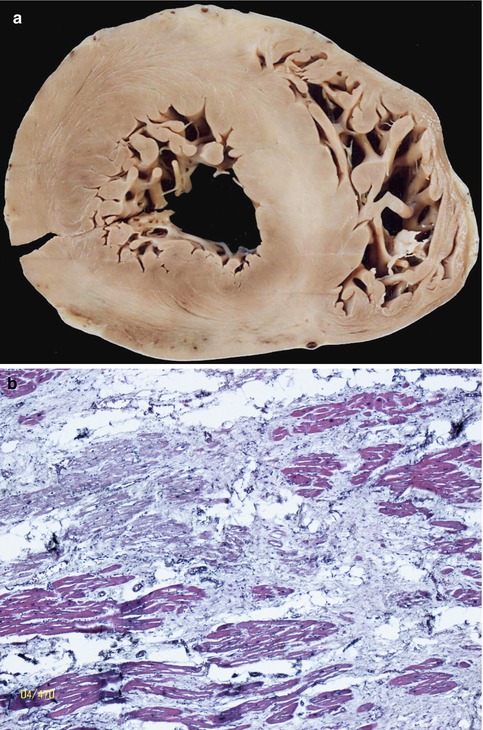

Fig. 9.9

Chronic myocarditis. (a) Macroscopic section of the heart showing large whitish areas of scarring in septum and free wall of the LV. Coronary arteries were permeable. This type of fibrosis distribution that does not follow the coronary flow is suggestive of chronic myocarditis. (b) Image shows an area of replacement fibrosis in the absence of inflammatory infiltrate. Lesions were not predominantly subendocardial (typical of ischaemic lesions)

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree