, Domenico Corrado2 and Cristina Basso1

(1)

Cardiovascular Pathology Department of Cardiac, Thoracic and Vascular Sciences, University of Padua, Padova, Italy

(2)

Cardiology Department of Cardiac, Thoracic and Vascular Sciences, University of Padua, Padova, Italy

Acute inflammation of the myocardium is another major cause of SCD in the young, particularly in children and adolescents [1–13]. The mechanism is mostly arrhythmic, since the affected young usually die without previous signs or symptoms and often during exercise performance.

At autopsy, the heart does not necessarily show ventricular dilatation and may appear grossly normal [7, 8, 13] (Fig. 5.1). At histology of the ventricular myocardium, patchy, either focal or diffuse, inflammatory infiltrates, together with interstitial edema and myocyte necrosis, may be found (Figs. 5.2–5.4). This pattern is quite different from that of fulminant myocarditis, associated with acute ventricular decompensation, pump failure, and cardiogenic shock, in which massive inflammatory infiltrates and cardiomyocyte necrosis are present. The inflammatory infiltrate usually consists of lymphocytes or may be polymorphic, with lymphocytes mixed to neutrophils/eosinophils [13, 14]. Immunostaining is essential for inflammatory cells characterization and is of help in patchy, focal forms (Fig. 5.5). This mild myocardial inflammation is enough to dysregulate the electrical order of the heart, enhancing the ectopic automatic mechanism of impulse onset. Release of cytokines, with interstitial edema and focal, patchy necrosis, may jeopardize the depolarization–repolarization phases of the myocardium, thus favoring triggered activity. In the subacute-chronic stages of myocarditis, varying degrees of replacement-type fibrosis might also account for electrical instability, with or without persistent inflammation (healing or healed myocarditis) (Fig. 5.6).

Among the various causes of myocarditis (infections, allergens, drugs, toxic agents, autoimmune reaction), viral infection is the most frequent etiology in SCD cases [7, 14–17].

Employment of PCR techniques, even in paraffin-embedded tissue, allows the identification of the causative infective agent [7, 14, 16]. In our experience (unpublished data), PCR was virus positive in 60 % of cases, with enterovirus ranking first, thus confirming the cardio-tropism and malignant behavior of coxsackievirus myocardial infection, also in terms of arrhythmic risk. However, a large spectrum of viruses can be found at molecular autopsy, including DNA viruses like adenoviruses. The mechanism of myocardial injury by coxsackievirus consists of the release of a protease (2A), which cleaves dystrophin and collapses the cytoskeleton. By the way, coxsackievirus B and adenovirus share the same receptor (CAR) in the myocyte membrane [18, 19].

Exceptional nonviral causes of infective myocarditis have been also reported such as chlamydia pneumonia [20, 21], Whipple disease [22, 23], or tuberculosis [24]. Clinical presentation of myocarditis may be various (angina/myocardial “infarction” like, cardiogenic shock, arrhythmias), and endomyocardial biopsy is indicated as gold standard for diagnosis [14, 15, 25–27]. Of course, the study of myocardial samples should include molecular investigation to establish a causative viral agent.

The reported prevalence of myocarditis in SCD series varies from 2 to 42 %, questioning the diagnostic criteria employed at histology [7, 16]. Rare lymphocytes (<7/mm2) in the myocardial interstitial space are a normal finding and by no way should be interpreted as a sign of myocarditis. We wonder how many cases of ion channel disease, as the true cause of SCD in the setting of a normal heart, have been misinterpreted as myocarditis [28, 29]. In a patient with arrhythmic presentation and myocarditis diagnosed by endomyocardial biopsy, an electrical storm may be pending so that temporary implantation of jacket defibrillator is indicated until resolution [15]. Respiratory or gastroenteric infections are quite common and may be that mild involvement of the myocardium occurs much more frequently than usually believed. Avoiding effort during fever of any infective origin is advisable.

SCD is rarely the clinical manifestation of giant cell myocarditis, which rather presents with cardiogenic shock [15]. On the opposite, cardiac sarcoidosis, either isolated or in the context of systemic disease, can be a cause of life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias and SCD even as first disease manifestation [30–32], as to mimic arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy [33] (Fig. 5.7).

Last but not least, toxicologic investigation is mandatory, to rule out unnatural causes, particularly in young adults and competitive athletes. For instance, myocarditis is a well-known cocaine-related cardiovascular complication [34–36]. It is mostly referred to as transient toxic cardiomyopathy, similar to catecholamine cardiomyopathy of pheochromocytoma. Excess catecholamines leading to myocyte damage, due to calcium overload or transient coronary vasoconstriction with ischemic injury, are possible pathophysiologic mechanisms. It is still a matter of debate whether inflammatory infiltrates are a secondary reaction to myocyte death or whether they represent a primary hypersensitivity reaction to cocaine. Eosinophilic infiltrates usually suggest allergic diathesis or reaction to drug therapy (Fig. 5.8). While cocaine cardiotoxicity is often a cause of hypersensitivity myocarditis, anabolic androgenic steroids mostly accounting for lymphocytic myocarditis and dilated cardiomyopathy [37] (Fig. 5.9).

5.1 Image Gallery

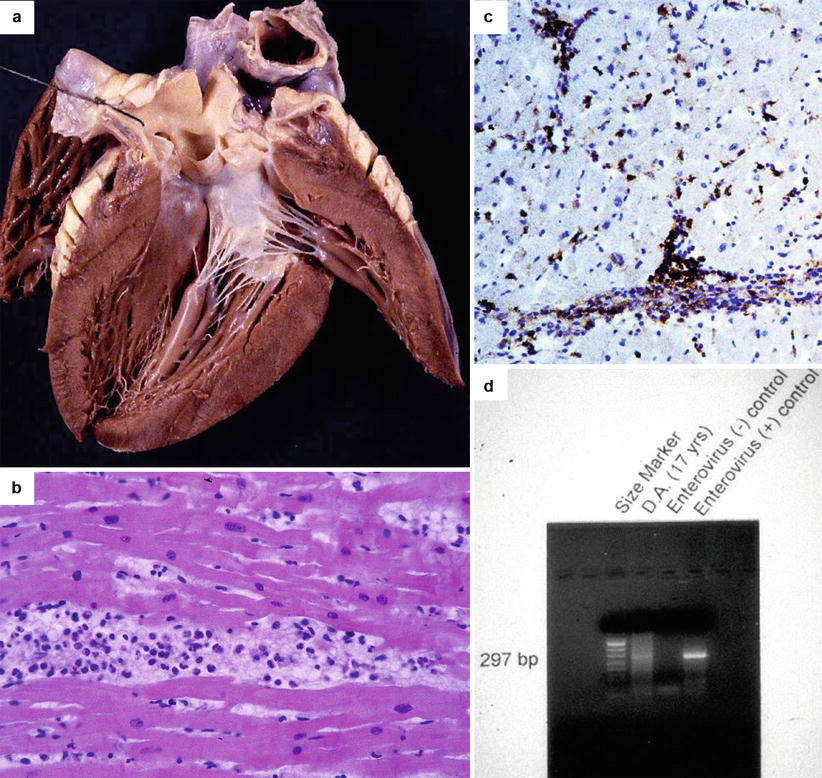

Fig. 5.1

Arrhythmic sudden cardiac death due to viral lymphocytic myocarditis in a 17-year-old boy who had a gastrointestinal flu 1 week before. (a) Grossly normal heart at autopsy. (b) Diffuse inflammatory cell infiltrates associated with interstitial edema and myocyte necrosis (hematoxylin–eosin). (c) At immunohistochemistry, the inflammatory infiltrate is rich in T lymphocytes (CD43 immunostaining). (d) PCR-proven acute myocarditis due to enterovirus infection

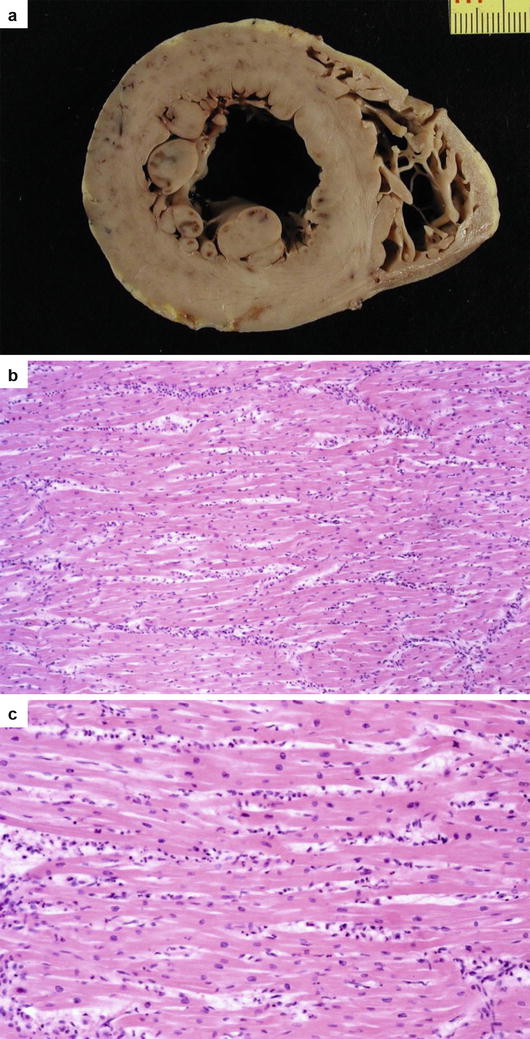

Fig. 5.2

Arrhythmic sudden cardiac death due to polymorphous myocarditis in a 9-year-old boy on effort. (a) Cross section of the heart with some subendocardial ischemia–reperfusion injury following cardiac arrest. (b) Diffuse inflammatory cell infiltrates associated with interstitial edema and myocyte necrosis (hematoxylin–eosin). (c) At higher magnification, polymorphous inflammatory cells including neutrophils and eosinophils (hematoxylin–eosin)

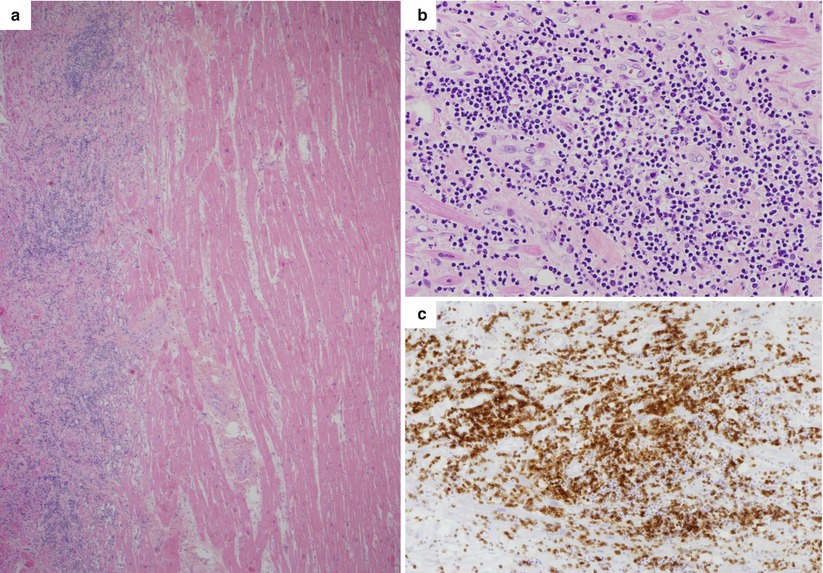

Fig. 5.3

Arrhythmic sudden cardiac death on effort due to lymphocytic myocarditis in a 22-year-old basketball player athlete. (a) Panoramic histology of the left ventricle: note the interstitial edema and massive inflammatory infiltrates in the outer layer of the left ventricular free wall (hematoxylin–eosin). (b) At higher magnification, diffuse polymorphous cell inflammatory infiltrates associated with myocyte necrosis (hematoxylin–eosin). (c) At immunohistochemistry, abundant T lymphocytes are seen (CD3 immunostaining)

Fig. 5.4

Arrhythmic sudden cardiac death due to viral lymphocytic myocarditis in a 6-year-old girl with a history of flu 5 days preceding cardiac arrest. (a) Diffuse interstitial edema and inflammatory infiltrates (hematoxylin–eosin). (b) At higher magnification, focus of inflammatory infiltrate associated with myocyte necrosis (hematoxylin–eosin). (c) At immunohistochemistry, the inflammatory infiltrate is rich in T lymphocytes (CD3 immunostaining). (d) PCR-proven lymphocytic myocarditis due to enterovirus infection

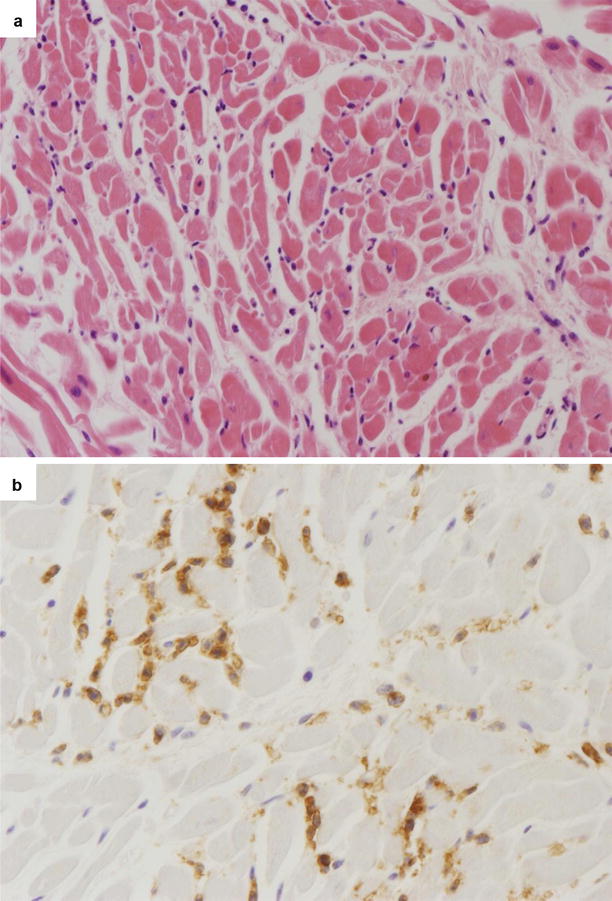

Fig. 5.5

Arrhythmic sudden cardiac death due to patchy lymphocytic myocarditis in a 25-year-old man at rest with a grossly normal heart. (a) Scattered inflammatory infiltrates (mononuclear cells) are visible in the myocardium (hematoxylin–eosin). (b) At immunohistochemistry, T lymphocytes are evident in the interstitium (CD3 immunostaining)

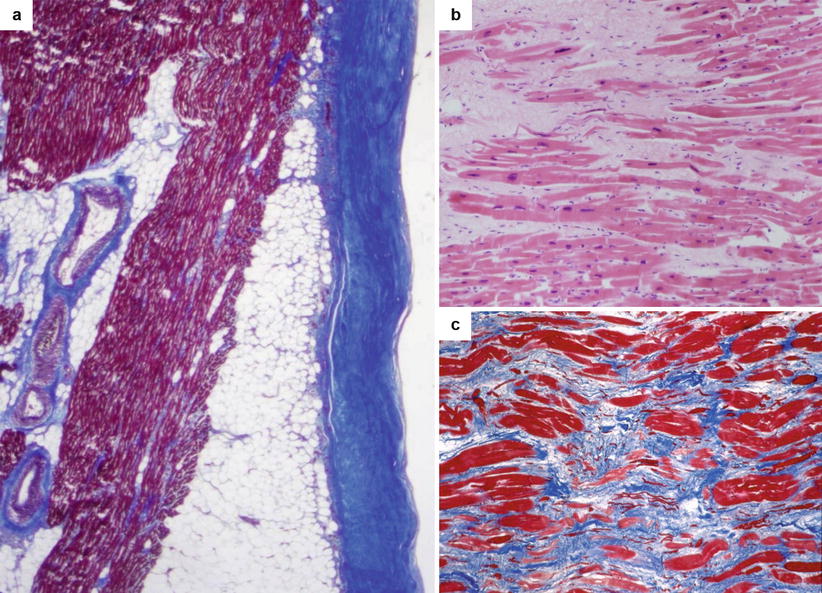

Fig. 5.6

Arrhythmic sudden cardiac death in a 26-year-old man on effort due to healed myopericarditis. (a) Histology of the right ventricular free wall: note the thickened, fibrotic pericardium (Heidenhain trichrome). (b) At higher magnification, histology of both the right and left ventricular myocardium shows patchy areas of replacement-type fibrosis (hematoxylin–eosin). (c) Other field with patchy fibrosis (Heidenhain trichrome)

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree