INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONS

The indications for the use of a muscle flap vary considerably depending on the pathology and the clinical situation. Muscle flaps are used to bring well-vascularized tissue to an area that has been damaged by radiation or infection. For example, in patients with radiation necrosis of the chest wall after external beam irradiation for breast cancer, a muscle flap can provide new vascularized tissue to cover the reconstruction of the chest wall. Muscle flaps can also provide coverage for an area with impaired healing. In the case of a bronchopleural fistulae with an infected bronchial stump, a muscle flap transposed through the chest wall into the pleural cavity can cover the newly closed bronchial stump and even though the edges of the bronchial closure may not stay approximated, the presence of a muscle flap covering the stump will prevent leakage of air or purulent material into the pleural cavity. Muscle flaps can also be placed on bronchial stumps prophylactically as in the patient who has had high-dose radiation therapy prior to resection.

Another major indication for the use of muscle flaps in thoracic surgery is to act as space filler. A typical example is in a patient who has a space after a lobectomy and a persistent air leak. By placing a muscle flap into the pleural space, the empty pleural space is obliterated allowing the air leak to heal. Muscle flaps can also be used to fill infected spaces, such as in the patient with an empyema whose decortication does not permit the lung to expand to fill the pleural space. Using a muscle flap in this circumstance will obliterate the potential space and bring well-vascularized tissue into the area to assist in healing the infection.

Another use for muscle flaps is to separate tissue. The classic example is using a muscle flap to separate the trachea and esophagus after a tracheoesophageal fistula repair. The interposed muscle will prevent the adjacent suture lines on the trachea and esophagus from coming together to reform the fistula.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

The use of muscle flaps to control infection, obliterate dead space, or separate tissue is not a commonly used technique. It is only necessary when other less traumatic techniques have not been successful or the patient has a unique problem. For most empyema the treatment is antibiotics and early drainage, before significant fibrosis of the pleural contaminants occurs. Early drainage will cure the vast majority of patients. When empyemas are treated late a decortication may be necessary. To perform a decortication there must be a plane between the lung and the fibrotic peel or excessive bleeding and air leakage will occur. There must also be a lung underneath the fibrous peel that can expand to fill the pleural space. If either of these conditions does not exist, decortication will be unsuccessful and some sort of space filler will be needed. When there is a bronchopleural fistula present this must be closed and reinforcement with a muscle flap is an excellent means to prevent reopening of the bronchial stump.

Most patients who present with the need for a muscle flap to correct some chest wall or pleural pathology have significant deficiencies in nutrition and have been sedentary for quite some time. Both of these problems should be addressed prior to undertaking reparative surgery of the magnitude that involves a muscle flap. Enteral feeding and physical rehabilitation can be undertaken well in advance of the reconstructive operation. While the rehabilitation is ongoing, infection should be controlled by antibiotics and any collections of purulent material drained. This may require an open window into the pleural space and repeated dressing changes before definitive reconstruction is undertaken. If a large bronchopleural fistula is present this should be closed and the infection drained before reconstruction is done.

The choice and use of muscular flaps should be made preoperatively in conjunction with a qualified plastic surgeon. It is possible for a thoracic surgeon to raise a simple muscle flap without the assistance of a plastic surgeon, but if the initial muscle flap fails, it sure is helpful to have had the plastic surgeon involved from the beginning, so the secondary options have been thought out. The size and location of the defect should be well known in advance. With current imaging technology, the three-dimensional configuration of the defect can be determined allowing for selection of the appropriate reconstructive technique. The thoracic surgeon should be well aware of previous operations that may have damaged the blood supply to various muscles of the chest wall that therefore make them nonviable options. Examples include the use of the left internal mammary artery would make the use of a left rectus muscle based on the superior epigastric vessel a poor choice, or a prior thoracotomy may have divided the latissimus dorsi muscle on the ipsilateral side, making its use less desirable.

Patients can usually be positioned in the lateral decubitus position for easy access to the pleural cavity as well as harvesting the muscles of the chest wall. If a skin graft is going to be necessary, the lateral thigh can be prepped into the field as well.

SURGERY

SURGERY

Pectoralis Major Muscle Flap

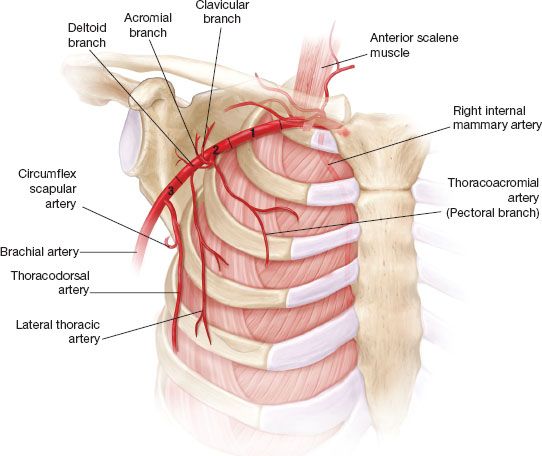

The pectoralis muscle, along with the serratus anterior, pectoralis minor, and subclavius, is one of the four muscles that keep the pectoral girdle attached to the chest wall. It originates from the medial portion of the clavicle and from along the lateral sternal border and upper costal cartilages. The muscle converges laterally and inserts on the intertubercular groove of the proximal humerus. Its main function is to facilitate adduction and internal rotation of the humerus. The anterior axillary fold is made up from its lateral muscle fibers. The vascular supply to the pectoralis major is mainly via the thoracoacromial artery with some perforators that come through the chest wall from the internal mammary artery (Fig. 50.1). The thoracoacromial artery arises from the second portion of the axillary artery and then courses laterally. It divides into four branches as it passes through the clavipectoral fascia: Clavicular, pectoral, acromial, and humeral branches. Detailed knowledge of the course of these vessels is important when harvesting the muscle for use.

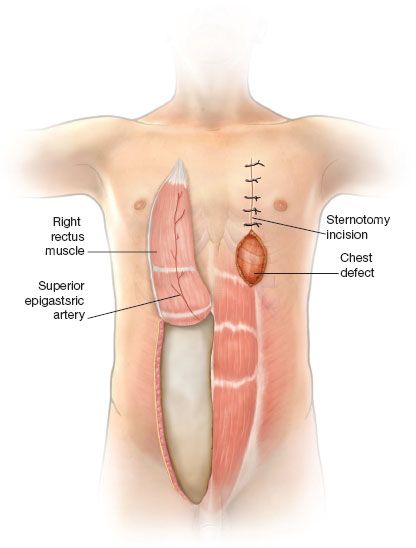

The pectoralis major muscle is usually used as an advancement flap to cover an infected sternum but can occasionally be used to fill pleural cavity defects, by detaching the insertion on the humerus (Fig. 50.2). To harvest the muscle as an advancement flap to cover a sternal defect or infection the muscle is raised from medial to lateral off the chest wall. Perforators from the internal mammary artery should be ligated. Do not free too much of the subcutaneous tissue off the anterior surface since this may interfere with the skin’s blood supply and impair healing of the incisions. The muscle will usually reach to cover a midline defect, but occasionally the insertion onto the humerus needs to be divided via a second incision to allow greater mobility.

Figure 50.1 Axillary artery. Cut away view of the right axillary artery and its branches showing the principal blood supply to the pectoralis major muscle (thoracoacromial artery), the latissimus dorsi muscle (thoracodorsal artery), and serratus anterior muscle (circumflex scapular artery).

Figure 50.2 Pectoralis major muscle flap. Lateral view of elevation of the pectoralis major flap.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree