Reperfusion therapy reduces mortality in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarctions (STEMI). However, some patients may not receive thrombolytic therapy or undergo primary percutaneous coronary intervention. The decision making and clinical outcomes of these patients have not been well described. In this study, 139 patients were identified from a total of 1,126 patients with STEMI who did not undergo reperfusion therapy at a high-volume percutaneous coronary intervention center from October 2006 to March 2011. Clinical data, reasons for no reperfusion, management, and mortality were obtained by chart review. The mean age was 80 ± 13 years (61% women, 31% diabetic, and 37% known coronary artery disease). Of the 139 patients, 72 (52%) presented with primary diagnoses other than STEMI, and 39 (28%) developed STEMI >24 hours after admission. The most common reasons for no reperfusion were advanced age, co-morbid conditions, acute or chronic kidney injury, delayed presentation, advance directives precluding reperfusion, patient preference, and dementia. Eighty-four patients (60%) had ≥3 reasons for no reperfusion. Factors associated with hospital mortality were cardiogenic shock, intubation, and advance directives prohibiting reperfusion after physician consultation. In hospital and 1-year mortality were 53% and 69%, respectively. In conclusion, at a high-volume percutaneous coronary intervention center, most patients presenting with STEMI underwent immediate catheterization. The decision for no reperfusion was multifactorial, with advanced age reported as the most common factor. Outcomes were poor in this population, and fewer than half of these patients survived to hospital discharge.

Reperfusion therapy reduces morbidity and mortality in patients with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarctions (STEMI). Current practice-based guidelines describe eligibility for revascularization in patients presenting with STEMIs. The decision to intervene in patients with few co-morbid conditions presenting with recent symptom onset and classic ST-segment elevation on electrocardiography (ECG) is straightforward. However, in practice, selection is more complex; delayed presentation, atypical symptoms, significant co-morbidities, and reasons for admission other than STEMI complicate the physician’s decision, which includes synthesis of subjective and objective information. Older patients, age, frailty, co-morbid conditions, ambiguous symptoms, and delay to emergency contact contribute to differences in guideline-driven therapy and mortality. A detailed analysis of why physicians decide not to send patients with STEMI to the catheterization laboratory has not been reported. We sought to determine the clinical factors that affect the decision not to refer patients for reperfusion therapy.

Methods

From October 2006 and March 2011, consecutive patients with STEMIs who were admitted to our institute and did not undergo reperfusion therapy for STEMI were included in our study. This study was approved by the Human Investigation Committee at Beaumont Hospital. Using the Beaumont registry and the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9), Clinical Modification coding database, all patients who were admitted with a diagnosis of STEMI and did not receive thrombolytic agents or undergo coronary angiography for percutaneous coronary intervention or bypass surgery were included in our study. In these patients, chart review was performed and ECGs were analyzed to verify that patients met criteria for STEMI. Criteria for STEMI were ischemic symptoms lasting ≥10 minutes within 72 hours of admission and ST-segment elevation in 2 contiguous leads.

All ECGs for the hospitalization were independently reviewed by a cardiologist to confirm that criteria were met using established criteria. ECGs representing posterior myocardial infarction, new left bundle branch block (LBBB), old LBBB with ≥1 criteria described by Sgarbossa et al, and left main coronary artery or multivessel obstruction were also included. ECGs were categorized by probable culprit vessel as either an anterior infarction including septal, anterior, lateral, and LBBB while inferior infarction included inferior and posterior myocardial infarctions. ECGs suggestive of multivessel or left main coronary artery disease were categorized in the anterior infarction group. If available, hospital ECGs were evaluated for ST-segment resolution within 2, 6, or 12 hours. The initial ECG was compared to previous ECGs if available.

Electronic and paper charts were reviewed to identify the primary reason for admission, presenting symptoms and duration, patient demographics, laboratory data, medications, reasons for no reperfusion, and mortality. Cardiogenic shock was defined as a sustained systolic blood pressure <90 mmHg for 30 minutes or requirement for inotropic or vasopressor support. Positive troponin was considered >0.05 ng/ml, and positive creatine kinase-MB was >5.0 ng/ml. When available, preadmission creatinine was compared to initial creatinine, and the presence of acute kidney injury and chronic renal insufficiency was recorded using established criteria. Guideline-driven medication therapy was recorded, including the use of aspirin, statin, β blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin-receptor blockers, clopidogrel or prasugrel, and heparin or enoxaparin. The use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors, inotropes, pressors, antibiotics, and antiarrhythmic agents were also recorded.

Reasons for no reperfusion included absolute and relative contraindications to reperfusion therapy as stated in the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association guidelines and additional reasons. Additional reasons in our registry included dementia, admission from an extended care facility, advance directives prohibiting reperfusion before admission or after discussion with the physician after evaluation for STEMI, acute or chronic kidney injury, “co-morbid conditions” written by the physician, and patient preference. Any and all reasons for no reperfusion were designated for each patient after chart review.

Mortality, including cardiac and noncardiac deaths, was obtained by chart review and from the Social Security Death Index.

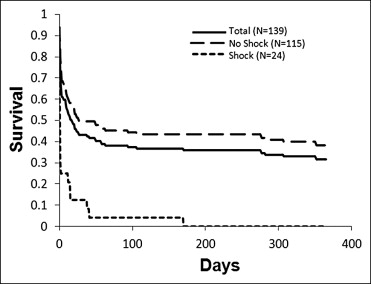

Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± SD or as percentages with corresponding 95% confidence intervals on the basis of the binomial distribution. A survival curve was generated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Agreement between the 2 reviewers of ECGs was assessed using Cohen’s κ coefficient for interrater agreement.

All analyses were performed using SPSS version 16.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, Illinois). Two-tailed p values <0.05 were considered significant. Univariate analysis was performed to identify independent predictors of mortality during the index hospitalization. Multivariate analysis using backward stepwise regression was performed to calculate odds ratios and their 95% confidence intervals. The fitted model was assessed using the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test. A receiver-operating characteristic curve and C statistic were generated to assess the predictive ability of the fitted model and the percentage of variation explained by the fitted model.

Results

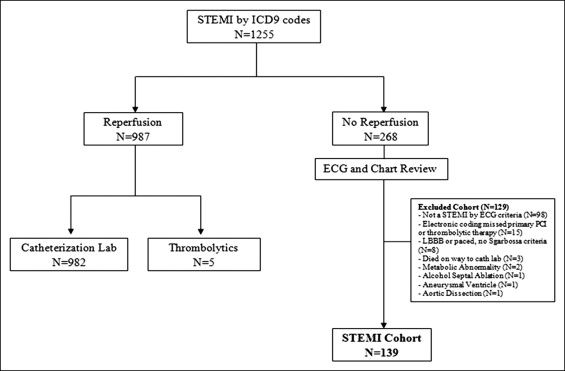

During the study period, 1,255 patients were admitted with a diagnosis of STEMI, and 984 patients received reperfusion therapy. Of the 268 patients who did not receive reperfusion therapy, 139 patients met criteria for new STEMI and were included in this analysis ( Figure 1 ). After chart and ECG review, the primary reason for exclusion (76%) was the ECG not meeting criteria for STEMI.

Baseline clinical characteristics of our study population are listed in Table 1 . Primary admission diagnoses other than STEMI occurred in 67 patients (48%). One hundred patients (72%) presented to the emergency center or developed STEMIs within 24 hours of admission, while 39 (28%) developed STEMIs >24 hours after admission. Twelve patients (9%) required cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) either before admission or within the emergency center. On presentation, 24 patients (17%) were in cardiogenic shock, and 20 patients (14%) required immediate intubation.

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 80.3 ± 13 |

| Men | 54 (39%) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 43 (31%) |

| Coronary artery disease | 52 (37%) |

| Previous coronary artery bypass grafting | 17 (12%) |

| Peripheral artery disease | 26 (19%) |

| Previous cerebral vascular accident | 30 (22%) |

| Hyperlipidemia ⁎ | 61 (44%) |

| Hypertension † | 98 (71%) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 25 (18%) |

| Cancer | 37 (27%) |

| Admitted from an extended care facility | 23 (17%) |

| Dementia | 28 (20%) |

| Reason for admission: myocardial infarction | 67 (48%) |

| Symptom onset >12 hours | 45 (32%) |

| Cardiogenic shock | 24 (17%) |

| CPR | 12 (9%) |

| Intubation | 20 (14%) |

| Anterior myocardial infarct | 78 (56%) |

| Inferior myocardial infarct | 61 (44%) |

| STEMI after 24 hours of admission | 39 (28%) |

⁎ Low-density lipoprotein >100 mg/dl or statin therapy before admission.

† Blood pressure >140/90 mm Hg or antihypertensive medication before admission.

The interrater reliability measurement between the 2 reviewers of ECGs for the presence of STEMI demonstrated almost perfect agreement (κ = 0.92). Seventy-eight patients (56%) were categorized as having anterior myocardial infarctions (67 anterior, 6 new LBBB, 1 LBBB with Sgarbossa criteria, 4 left main or multivessel), while 61 patients (44%) had ECGs consistent with inferior or posterior myocardial infarctions. Troponin or creatine kinase-MB was elevated in all patients who had laboratory results available.

Table 2 lists reasons why patients did not undergo reperfusion. Three patients refused catheterization despite recommendation by the cardiologist. Three or more reasons for no reperfusion and 2 reasons were identified in 84 (60%) and 36 (26%) patients, respectively.

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Delayed presentation (>12 hours) | 45 (32%) |

| Central nervous system (active intracerebral hemorrhage or <3 months, ischemic stroke, mass, aneurysm) | 11 (11%) |

| Bleeding (active, known diathesis, <4 weeks) | 25 (9%) |

| Trauma and closed head injury | 14 (10%) |

| Major surgery within 3 weeks | 13 (9%) |

| Dementia | 28 (20%) |

| Advanced age ⁎ | 69 (50%) |

| Co-morbid conditions † | 40 (29%) |

| Acute or chronic kidney injury | 53 (38%) |

| Known unsuitable coronary anatomy | 2 (1%) |

| Resolution of ST-segment elevation | 12 (9%) |

| Resolution of angina or equivalent | 22 (16%) |

| Patient preference | 31 (22%) |

| Advance directives before STEMI | 7 (5%) |

| Advance directives after physician discussion | 32 (29%) |

⁎ Age >85 years or documented as reason for no reperfusion.

Guideline-driven medical therapy with contraindications to specific medications is listed in Table 3 . Fourteen patients (10%) died <24 hours after arrival, and 32 (23%) had advance directives precluding guideline STEMI medical therapy.

| Medication | n (%) | Number of Patients With Contraindications |

|---|---|---|

| Aspirin | 120 (86%) | 12 (9%) |

| Heparin or low–molecular weight heparin | 96 (69%) | 30 (22%) |

| Clopidogrel or prasugrel | 60 (43%) | 27 (19%) |

| β blockers | 100 (72%) | 19 (14%) |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers | 74 (53%) | 21 (15%) |

| Statins | 88 (63%) | 1 (1%) |

Table 1 lists the clinical presentation of our study cohort. Only 2 patients (17%) who received CPR before admission or within the emergency center survived, while 1 patient (10%) admitted to the wards who required CPR survived hospitalization. Three patients (21%) who required intubation on presentation survived to be discharged. Hospital mortality for the patients who received reperfusion therapy during that same time period was 2.4%.

Seventy-three patients (53%) died during the index hospitalization, and 23 (17%) died <1 year after discharge. Twenty-two of the 24 patients (91.6%) presenting with cardiogenic shock died during the index hospitalization. Figure 2 shows the Kaplan-Meier survival curve for 1 year after admission. Mortality was higher in patients who presented with cardiogenic shock.