Mitral Insufficiency

Allen P. Burke, M.D.

Etiology

Similar to the aortic valve, regurgitation of the mitral valve may be caused by intrinsic mitral valve disease (myxoid degeneration resulting in prolapse), postinflammatory scarring with leaflet retraction, or factors not directly related to valve leaflets. In the last group are cardiomyopathies (ischemic or nonischemic) and ischemic damage (acute or chronic) involving the papillary muscles, most importantly the posteromedial papillary muscle.

Mitral Valve Prolapse

Background

Mitral valve prolapse is a disease of unclear etiology, genetics, and pathophysiology that has been recognized for more than a century.1,2 In the 1960s, Barlow et al. described the association between mitral prolapse and mitral insufficiency using cineventriculography.3 The eponymous term “Barlow mitral valve disease” is still used today for mitral valve prolapse.

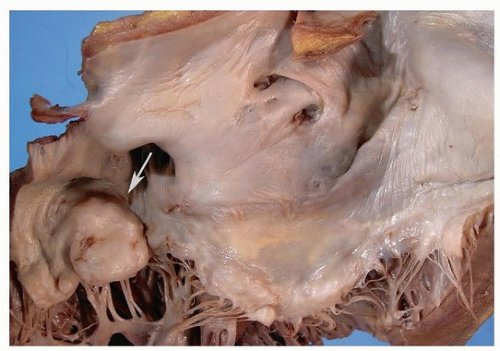

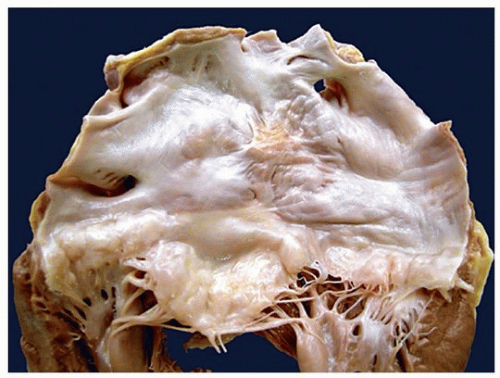

Mitral valve prolapse is a spectrum of valve disease ranging from functional prolapse without insufficiency to a billowed, thickened valve with chordal disarray and mitral insufficiency. The pathologic terms “floppy mitral valve” or “myxomatous mitral valve” are sometimes used for prolapsed valves with thickened, elongated leaflets.4

Mitral valve prolapse is defined echocardiographically as the systolic movement of mitral valve leaflets into the left atrium that exceeds 2 mm. By this definition, mitral valve prolapse is common, ranging from 1% to 2.5% in the United States.1 Pathologically, floppy mitral valve (or myxomatous mitral valve) is defined by valve elongation and chordal disarray, especially of the posterior leaflet, with accumulation of mucoid ground substance (myxoid change.)

The incidence floppy mitral valve is less than one-third that of functional mitral valve prolapse. Surgeons use the term “Barlow disease” specifically for prolapse with diffuse bileaflet thickening, ballooning of the leaflet and chordae, and annular dilatation. Mitral valve prolapse is frequently complicated by mitral regurgitation, but prolapse may occur in the absence of a regurgitant jet stream.1

Genetics of Mitral Valve Prolapse

Mitral valve prolapse is usually sporadic or nonsyndromic. Familial mitral valve prolapse occurs as an autosomal dominant trait with variable expressivity. Three loci for autosomal dominant, nonsyndromic mitral valve prolapse have been identified on chromosomes 16, 11, and 13.1 Although there is an association between mitral valve prolapse and Marfan syndrome, no connection has been made between sporadic mitral valve prolapse and fibrillin-1 mutations.

Clinical Findings

Patients with mitral valve prolapse are usually asymptomatic. The diagnosis is most often made incidentally at auscultation or echocardiography. There is a female predominance for functional mitral valve prolapse, but symptomatic disease with thickened regurgitant valves has no gender predisposition. Symptoms include heart palpitations and syncope and shortness of breath, chest pain, and panic attacks. Patients with mitral valve prolapse tend to have a low body mass index.

By echocardiography, both leaflets are involved in 40% of patients; in 60%, the disease is limited to the posterior leaflet. If mitral regurgitation complicates mitral valve prolapse, a pansystolic murmur can be heard. Other findings of mitral regurgitation, such as left

ventricular enlargement and left atrial dilatation, can also occur in late stages of the disease. Association with other valvular disorders is common and includes prolapse of the other three heart valves, with up to 40% of patients demonstrating tricuspid valve prolapse.1,5 The association between mitral valve prolapse and atrial septal defect is also recognized; in this case, the anterior, instead of the posterior, leaflet is generally involved, probably related to flow-induced valve billowing.

ventricular enlargement and left atrial dilatation, can also occur in late stages of the disease. Association with other valvular disorders is common and includes prolapse of the other three heart valves, with up to 40% of patients demonstrating tricuspid valve prolapse.1,5 The association between mitral valve prolapse and atrial septal defect is also recognized; in this case, the anterior, instead of the posterior, leaflet is generally involved, probably related to flow-induced valve billowing.

Complications are uncommon, but can lead to serious morbidity and mortality, including heart failure, progressive mitral regurgitation, bacterial endocarditis, thromboembolism, atrial fibrillation, and sudden death. These comorbidities affect <3% of subjects with mitral valve prolapse. 6 Sudden death from mitral valve prolapse is rare, and ventricular arrhythmias are the most likely cause (see Chapter 141). The mechanism of sudden death is poorly understood. Extravalvular cardiac pathology, in particular intramural artery dysplasia and fibrosis in the base of the interventricular septum, has been reported in a high percentage of cases of mitral valve prolapse and may play a role in the formation of arrhythmias.7

Gross Pathologic Findings, Autopsy

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree