Miscellaneous Respiratory Infections

Introduction

The diseases described in the previous chapters of this atlas are all prevalent throughout the world, although their incidence may vary somewhat between different regions. However, some infections which affect the respiratory system have a much more restricted geographical prevalence. While physicians practising in an area where such a disease is endemic may quickly recognize its manifestations, the diagnosis may be easily missed when the patient presents in a country where the disease is rarely encountered. There are many of these ‘exotic’ and rare diseases, but some are of sufficient importance to warrant their inclusion in this atlas. These include hydatid disease, histoplasmosis, coccidiomycosis, and tropical pulmonary eosinophilia. Also included are two diseases, actinomycosis and nocardiosis, which, although rare, are indigenous to most countries. This chapter starts with the investigation, diagnosis, and management of aspiration pneumonia which is not rare and is seen in both hospital and community practice.

Aspiration pneumonia

There are many causes of aspiration pneumonia, but some of the common risk factors include:

General anaesthesia.

Cerebrovascular disease.

Impaired consciousness, e.g. epilepsy.

Neurological disease, e.g. Parkinson’s.

Oesophageal pathology, e.g. benign or malignant stricture or oesophageal web.

Self poisoning, e.g. opiate overdose.

Aetiology

Aspiration pneumonia is caused by organisms that are normal commensals of the oropharynx, or by gastrointestinal or environmental organisms that have replaced the normal flora of the oropharynx because of antibiotic therapy, intubation, or concurrent debilitating illness. In patients who have not been recently in acute hospital care, organisms that are responsible may include anaerobic cocci, anaerobic Gram-negative bacilli, such as Bacteroides spp. and fusiforms, oral streptococci such as those of the Streptococcus milleri group, coliform organisms such as Klebsiella or Enterobacter spp., and Staphylococcus aureus.

In hospitalized patients, more resistant organisms may be involved, including antibiotic-resistant coliforms, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Acinetobacter spp., methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and yeasts such as Candida albicans. Often, more than one organism may be involved.

Investigations

The following investigations are standard:

Chest radiograph.

Sputum Gram stain, culture (including anaerobic), and sensitivity testing if samples are available.

Blood cultures.

If the patient is ventilated, tracheal aspirates or, if indicated, bronchoalveolar lavage.

Blood tests including full blood count, inflammatory markers such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C reactive protein, urea and electrolytes, and liver function tests.

7.2 Macroscopic picture of a lung showing an area of consolidation with abscess formation secondary to aspiration pneumonia (arrow). |

Illustrative cases

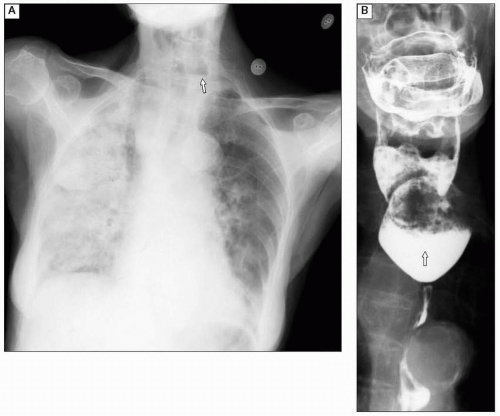

A chest radiograph is presented in 7.1A, showing extensive bilateral pneumonia due to a pharyngeal pouch. Note the air/fluid level in the neck. The barium swallow (7.1B) confirms there is a pharyngeal pouch.

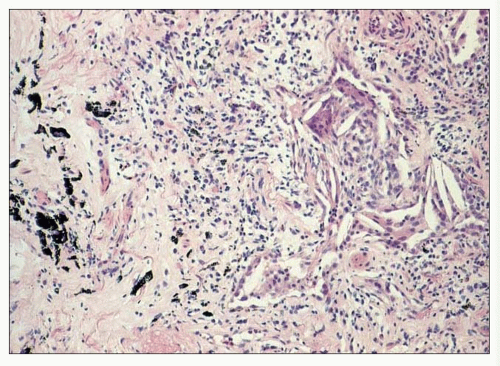

Figure 7.2 is a macroscopic picture of a lung showing an area of consolidation with abscess formation secondary to aspiration pneumonia. The abscess is cavitated and has a thickened fibrous wall. Macroscopically the appearance is similar to that which may be seen with any other cause of chronic abscess formation. Histologically, aspiration pneumonia may show a wide range of appearances depending on the nature of the aspirated material. Foreign material, such as vegetable matter and lipid, may be seen if food material is aspirated. If gastric acid is aspirated then the pattern may be nonspecific and resemble acute interstitial pneumonitis with fibrin leak into airspaces. The photomicrograph from a case of aspiration pneumonia (7.3) shows a prominent foreign body giant cell reaction to lipid. The lipid has been lost from the section and is represented by the cleft-like spaces in the giant cells.

Therapy

Treatment for aspiration pneumonia is often empirical. Oxygen is given if the PaO2 on air is <7.3 kPa. Fluids are recommended to maintain hydration. In patients with nonresistant organisms, a recommended first-line antibiotic treatment is co-amoxiclav or a combination treatment with cephalosporins, such as cefuroxime, cefotaxime, or ceftriaxone and metronidazole.

In patients in whom there is concern of more resistant organisms, a more intensive regimen is given. Ideally, this should be based on culture and sensitivity results. If none are available a regimen including vancomycin and meropenem is often used.

Histoplasmosis

Histoplasmosis is a chronic airborne fungal infection which often presents with clinical and radiological features closely resembling TB.

Aetiology

Histoplasmosis is caused by the inhalation of the spores of a fungus which has yeast-like morphology when it infects mammals. This form of the fungus is known as Histoplasma capsulatum. The mycelial form of the fungus, which produces the infective spores, is widely distributed as point sources associated with bat and avian excrement in many tropical and temperate areas, particularly in south-central USA. Spores become airborne readily, and are of such a size as to reach the small bronchioles and alveoli easily when inhaled. They are ingested by macrophages, and a wide spectrum of reaction may ensue.

In most cases, there is an asymptomatic and successful immune response, but in a few patients proliferation of the ingested spores and foci of macrophage infiltration, leading to caseation and necrosis, may occur in the lungs, mediastinum, and other parts of the reticuloendothelial system (disseminated histoplasmosis). The clinical outcome depends on the amount of spores inhaled and the immune status of the patient. The yeast may lie dormant for long periods in the lung, and reactivates to produce lesions resembling TB (chronic pulmonary histoplasmosis). These foci of reactivation are often related to centrilobular or bullous airspaces in emphysema.

Illustrative cases and investigations

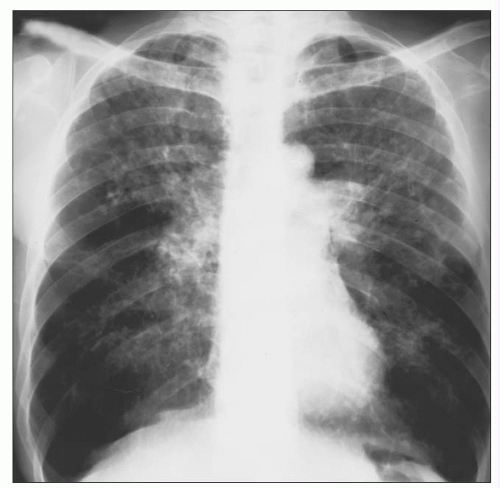

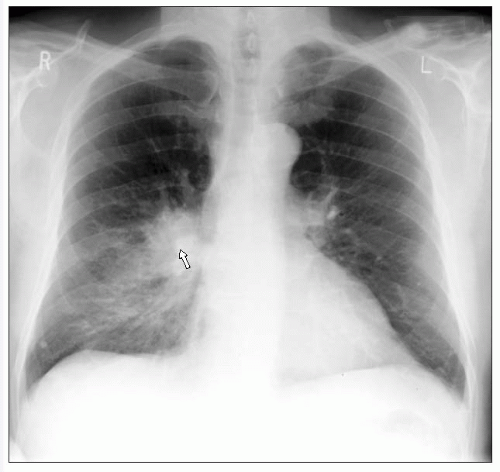

The chest radiograph shown in 7.4 is from a patient with emphysema who presented with fibrocavitatory disease (particularly in the upper lobes) due to histoplasmosis. There can be different chest radiograph findings in histoplasmosis. There may be a single small or large lung focus with or without associated hilar lymphadenopathy, it can present with a diffuse miliary pattern usually with associated hilar lymphadenopathy, and it can present with fibrocavitatory disease similar to TB. Calcification can subsequently be seen following healing.

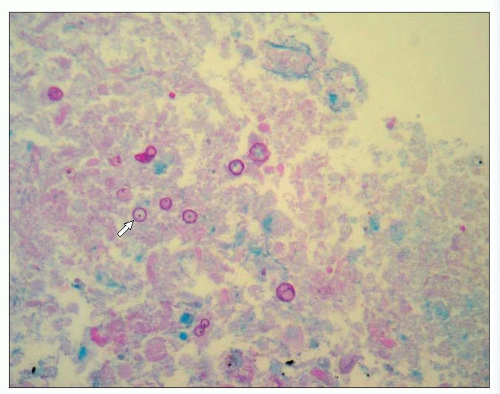

Tissue samples from lesions of disseminated histoplasmosis and sputum (or bronchoalveolar lavage) in chronic pulmonary histoplasmosis may be cultured on mycological culture media. Culture is often negative, since organisms may be scanty. Growth is slow (2—4 weeks). Microscopy of Giemsa-stained preparations of bronchoalveolar lavage, or preparations of tissue biopsies stained with periodic acid Schiff (PAS) or methenamine silver may provide rapid diagnosis, but require expertise. Histologically the appearance of histoplasmosis in the lung is very similar to that of fibrocaseous TB. Differentiation of the two conditions histologically relies on the use of PAS and Ziehl-Neelsen stains, although in some cases no organisms may been seen and further microbiological investigation will be required. Figure 7.5 is a photomicrograph of a lung section from a case of histoplasmosis, stained with PAS which stains the capsules of the spores red.

High antibody titres (complement fixation) may support the diagnosis, especially in nonendemic areas. Titration of blood or urine antigen levels using radioimmunoassay may be of value in monitoring therapy in AIDS patients. Skin testing is of value in epidemiological studies, but is not so useful in clinical diagnosis.

Therapy

Most cases of acute histoplasmosis resolve without specific therapy.

All cases of disseminated histoplasmosis or chronic pulmonary histoplasmosis need specific antifungal therapy. Treatment is started with amphotericin B, and may be continued with oral itraconazole for 6—12 months. Treatment is continued for life in patients with AIDS.

7.4 Chest radiograph from a patient with emphysema who presented with fibrocavitatory disease (particularly in the upper lobes) due to histoplasmosis. |

7.5 Photomicrograph of a section of lung from a patient with histoplasmosis, stained with PAS which stains the capsules of the spores red (arrow). |

7.6A Chest radiograph showing a prominent right hilum and distal consolidation (arrow) due to coccidiomycosis. |

Coccidiomycosis

Coccidiomycosis is a chronic lung infection caused by inhalation of fungal spores. Most infections are mild or asymptomatic, the area of focal pneumonitis healing spontaneously to leave a coin-like scar (coccidioma) or a single, small, thin-walled cavity. In a few cases, symptomatic consolidation occurs with fever, malaise, cough, and chest pain, and may progress to chronic fibronodular disease of the lung or hilar lymph nodes. Dissemination beyond the lung or hilar nodes occurs rarely. Disseminated disease is more likely in immunocompromised patients, and carries a poor prognosis. The CNS, musculoskeletal system, and skin are particularly involved.

Aetiology

Coccidiomycosis is caused by inhalation of the wind-borne spores (spherules) of a soil fungus, Coccidioides imitis, found in the desert regions of south-western USA, Mexico, and central and South America. Person-to-person transmission does not occur.

Illustrative cases and investigations

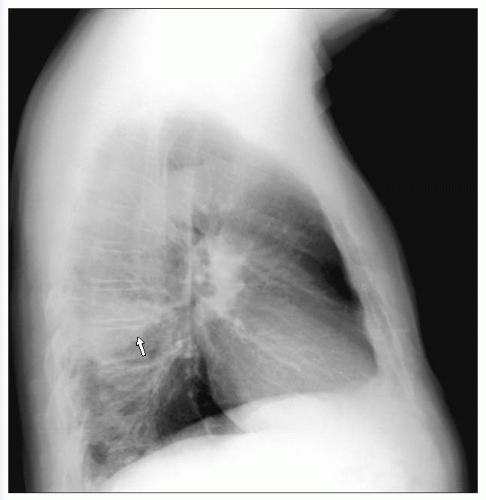

A 68-year-old man presented with a lower respiratory tract illness following his return from Arizona. The chest radiograph (7.6A) shows a prominent right hilum with distal consolidation. The lateral film (7.6B) reveals an area of homogenous increased density within the apical segment of the right lower lobe. In the CT scan (lung window setting; 7.6C) a dense mass is seen in the right lower lobe, suspicious of a bronchial neoplasm. A percutaneous CT-guided biopsy confirmed necrotizing granulomatous inflammation with associated fungal spores consistent with coccidiomycosis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree