Metastatic Cancers

Keith M. Kerr FRCPath

The lungs are the most common site, after the liver, for metastatic cancer, and, as a clinical problem, pulmonary metastases are more frequently encountered than primary carcinoma of the lung. In around 15% to 25% of cases, the lung is the sole site of metastatic disease. In most instances, metastases are multiple. When they are solitary they may present an important differential diagnosis with primary carcinoma. Approximately 28% of lung metastases originate from the gastrointestinal and genitourinary tracts, respectively, 17% from the female breast, and 11% are metastatic sarcomas.

Most lung metastases are peripheral subpleural lesions that are not accessible to bronchial biopsy but may be sampled by transbronchial biopsy, especially if the bronchoscopist knows which bronchopulmonary segment to target. Atypical patterns of metastases occur in 9% of patients and include solitary lesions, cavitation, central/hilar location, endobronchial tumor, hilar/mediastinal lymphadenopathy, and superior sulcus lesions with neurologic syndromes; all features suggestive of primary carcinoma.

Around 30% to 40% of solitary pulmonary metastases are colorectal in origin with breast, kidney, bladder, and testis accounting, in descending order of frequency, for many of the remainder. Endobronchial metastases are most frequently from breast, colorectal, and renal cell carcinomas, melanoma, or sarcoma, again in descending order of frequency. This is very much reflected in the experience of metastatic disease encountered in bronchial biopsy samples. Metastases from pancreas, colon, and stomach may grow in a bronchioloalveolar pattern and thus may be found in transbronchial biopsy samples. Metastatic disease may be encountered in bronchial or transbronchial biopsies in the context of a number of differing clinical scenarios, such as multiple pulmonary lesions, solitary lung lesions mimicking primary tumor, known history of previous extrapulmonary malignancy, previous history of metastases at other sites, no known history of extrapulmonary malignancy either current or in the past, and useful or indicative history not communicated to the reporting pathologist.

Relatively few metastatic carcinomas are so distinctive that, even in the absence of a full history, the correct diagnosis will be made from the histologic examination of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained sections. Almost all the commonly encountered metastatic tumors have close equivalent primary lung tumors. Thus in the absence of any clinical history, many metastatic tumors may not be recognized because their features are perfectly acceptable as primary disease. Equally, even if the pathologist knows about the possibility of metastatic disease, it may be a challenge to distinguish it from primary carcinoma. Diagnostic difficulty is compounded by the small amount of tumor usually available for examination.

Most lung metastases are adenocarcinomas. Primary lung adenocarcinoma is an extremely heterogeneous tumor and may show an acinar, cribriform, or even signet-ring cell pattern as seen in breast or many upper gastrointestinal carcinomas; the enteric pattern of adenocarcinoma with so-called dirty necrosis, typical of colorectal cancer, may occur as

a primary lung tumor, and clear cell variants of adenocarcinoma and large cell carcinoma may easily mimic metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Not all metastatic melanomas show melanin, and they can simulate large cell lung carcinoma with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and prominent nucleoli. Sarcomatoid carcinomas are named precisely for the reason that they are similar in appearance to a variety of true sarcomas, whereas neuroendocrine and squamous cell carcinomas look the same regardless of their origin.

a primary lung tumor, and clear cell variants of adenocarcinoma and large cell carcinoma may easily mimic metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Not all metastatic melanomas show melanin, and they can simulate large cell lung carcinoma with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and prominent nucleoli. Sarcomatoid carcinomas are named precisely for the reason that they are similar in appearance to a variety of true sarcomas, whereas neuroendocrine and squamous cell carcinomas look the same regardless of their origin.

Without an appropriate history, and accepting that primary lung cancer can show a very wide range of appearances, the pathologist should be aware of the possibility of metastatic disease and have a high index of suspicion if the tumor in a bronchial or transbronchial biopsy is in any way unusual. Apart from seeking further clinical or radiologic detail, immunohistochemistry is of vital importance in this area of differential diagnosis. Immunohistochemical profiles of different primary tumors are published in detail elsewhere, including descriptions of the relative discriminating power of various markers or groups of markers. There is no immunohistochemical solution to the problem of (possible) metastatic neuroendocrine or squamous cell carcinoma. Lung adenocarcinomas express CK7 but only rarely CK20, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) in 95% of cases and thyroid transcription factor-1 (TTF-1) in 75% of cases. TTF-1 is particularly useful in identifying primary lung cancer when thyroid or neuroendocrine carcinoma is ruled out by other means. The CK20+/CK7–/CDX2+/MUC2+ profile of most colorectal carcinomas is very useful, but enteric-pattern primary lung adenocarcinoma may also show this combination, although CDX2 is less often positive. TTF-1 may be present in the lung version of this tumor, and both CK20 and MUC2 are found only occasionally. Mucinous bronchioloalveolar carcinomas are frequently CK20 positive but do not express CDX2. Renal cell carcinomas do not produce mixed neutral and acidic mucins and may express CD10. Prostate and breast carcinomas may be identified by the presence of PSA (or prostatic acid phosphatase) and ERalpha, respectively. S-100, MelanA, and HMB45 are most useful in the identification of melanoma.

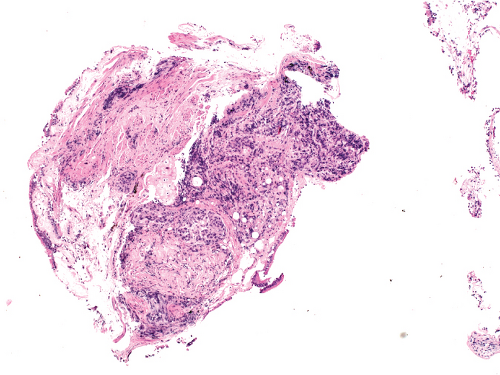

Figure 5.1: Metastatic breast cancer. Bronchial biopsy covered by respiratory epithelium and infiltrated by tumor. This biopsy was accompanied by a history of previous ductal carcinoma of the breast.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|