Heart disease is a major cause of hospitalization and is associated with greater impairment than arthritis, diabetes mellitus, or lung disease. Depression is prevalent and a serious co-morbidity in heart disease with negative consequences including higher levels of chronic physical illness, decreased psychological well-being, and increased health care costs. The objective of the study was to examine with meta-analysis the impact of community-based cardiac rehabilitation (CR) treatment on depression outcomes in older adults. Randomized controlled trials comparing patients (≥64 years old) receiving CR to cardiac controls were considered. Meta-analyses were based on 18 studies that met inclusion criteria, comprising 1,926 treatment participants and 1,901 controls. Effect sizes (ESs) ranged from −0.39 (in favor of control group) to 1.09 (in favor of treatment group). Mean weighted ES was 0.28, and 11 studies showed positive ESs. Meta-analysis suggests that most CR programs delivered in the home can significantly mitigate depression symptoms. Tailored interventions combined with psychosocial interventions are likely to be more effective in decreasing depression in older adults with heart disease than usual care.

Previous meta-analyses have determined that community-based cardiac rehabilitation (CR) and psychosocial interventions for patients with heart failure (HF) and coronary artery disease (CAD) decrease mortality and improve health-related quality of life. However, previous published studies have rarely focused on the geriatric population and many large trials including Montreal Heart Attack Readjustment Trial (M-HART) were undertaken in hospital settings, recruited men and/or patients <65 years old, or did not examine depression outcomes. Thus, our aim was to review randomized trials that examined the impact of community-based CR interventions on depression in older patients (≥64 years old) using meta-analysis. Studies included telehealth care, medical management, exercise, counseling, nutrition, Tai Chi, breathing, and mindfulness interventions. Effect sizes (ESs) were estimated for reported depression outcomes. Studies employed trained interventionists, recruited older samples diagnosed with HF or CAD, compared ≥2 treatments, and measured depression. The significance of this analysis may demonstrate that CR interventions have the potential to improve psychological status for the increasing older population with cardiac disease.

Methods

We conducted a systematic electronic search of the PsycINFO, PubMed, ClinialTrial.gov, Central Register of Controlled Trials, and CINAHL databases. Relevant treatment trials were searched using the following keywords: depress*, elder*, geri*, heart disease or heart failure, old*, randomized, and trial. We reviewed studies of community-based CR interventions offered in the home or outpatient clinic setting for older adults diagnosed with heart disease. For this review, heart disease was defined as a primary diagnosis of HF or CAD based on the American Heart Association/American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation (AACVPR) 2010 scientific consensus statement on CR. The search was limited to studies published from January 1998 through January 2012 and classified as randomized controlled trials investigating an effect of an intervention on depression outcomes. We limited the participants’ mean age to ≥64 years because of high prevalence rates of heart disease and co-morbid depression in older populations. We also limited studies to participants of community-based interventions and thus excluded samples of institutionalized patients. We excluded case and qualitative reports and studies without comparison groups. Authors reviewed all abstracts and articles to ensure they met the inclusion criteria.

We considered community-based treatments as home or outpatient based. We defined in-home treatment as a health service that took place at a patient’s residence. An outpatient intervention was defined as treatment that occurred in an outpatient CR clinic with similar components as in-home treatment. If an intervention involved >1 care setting, e.g., a disease management program held at an outpatient clinic with self-management activities at home, the study was classified as a combined home and outpatient intervention. Intervention components included some combination of heart health care management and/or education, counseling, exercise, or telehealth care. Usual care–control components typically were standard medical care that may have included a physician and/or specialist nursing care and heart education.

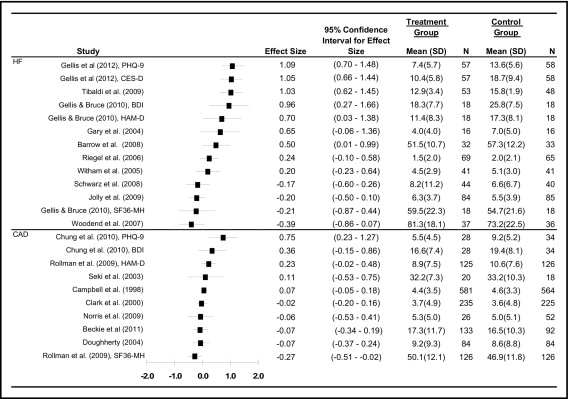

Meta-analysis was performed to estimate ESs for mean differences in depression outcomes between the treatment and control groups. ES was calculated as the standardized mean difference (Hedges) between the treatment and control groups at the most current follow-up assessment with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Eighteen studies were included and meta-analysis was performed on each mental health outcome reported in the selected articles. Three studies were excluded from the meta-analysis because of missing information on depression outcome means and SDs for the treatment and control groups. Study data were analyzed using a standard ES calculation tool.

Two reviewers independently screened abstracts and full articles and extracted data on treatment setting, sample size, sample mean age, gender, standardized depression measurements used, intervention format and duration, study location, and key findings for each study. The 2 reviewers independently noted methodologic details using a checklist including randomization, blinding of outcome assessment, and managing of attrition in the data analysis. The methodologic quality of these studies has been previously published.

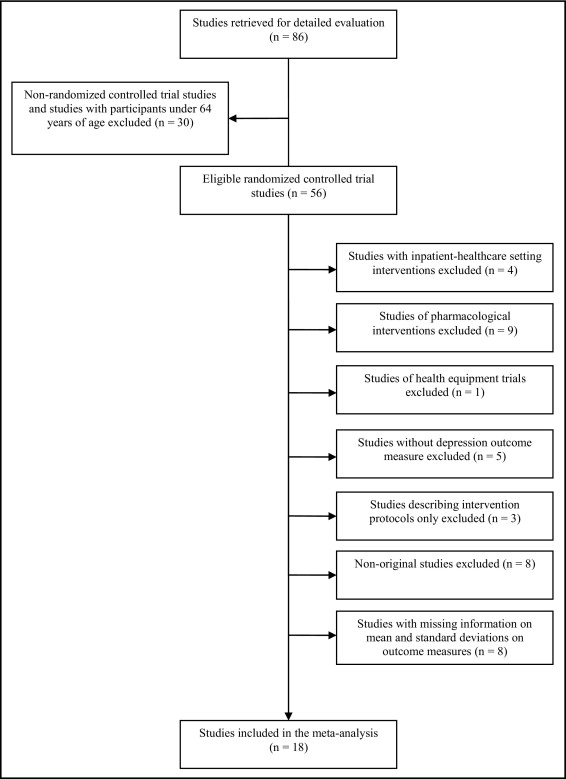

Figure 1 shows the various steps in the study inclusion and exclusion process. The search strategy initially yielded 86 articles. In the second review phase, 30 articles were excluded because of use of a nonrandomized design or the sample mean age was <64 years. In the next phase, another 38 studies were excluded for the following reasons: (1) inpatient setting intervention (n = 4), (2) pharmacologic intervention (n = 9), (3) health equipment trial (n = 1), (4) depression measurement excluded (n = 5), (5) randomized study protocol description only (n = 3), (6) nonoriginal descriptive study (n = 8), and (7) studies with missing information on means and SDs (n = 8).

Results

Eighteen studies of an elderly CR patient population were included in the analysis ( Table 1 ). The review was comprised of 9 studies conducted in the United States, 4 studies in the United Kingdom, 2 studies in Canada, 1 study in Italy, 1 study in Japan, and 1 study in Taiwan. In Table 1 , each study is assigned a reference number for ease of reading with uniformly extracted data and cited in the reference section. Overall, 3,827 patients were included: 1,926 assigned to the experimental condition and 1,901 to usual care. Overall mean age was 71 years (range 64 to 80). Sample sizes varied widely (range 32 to 570) with a mean sample size of 151.3 ± 197.2. Of the studies reviewed, 82% (n = 15) had a sample size of ≥50 participants, 4 reported 100% women, and 1 study had 100% men. Only 1 trial included >1,000 patients and only 1 trial had >6-month follow-up. However, previous meta-analyses included fewer and smaller trials and did not show a positive effect.

| Study | Number ⁎ | Diagnosis | Country | Gender | Mean Age (years) | Intervention | Duration (months) | Depression Measurement Used | Other Measurements | Depression Outcomes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | HB | OP | WT | S | QoL | A | ||||||||

| 1. Barrow et al (2007) | 65 | HF | UK | + | + | 69 | + | + | 4 | SCL 90-R | + | + | + | T > UC | |

| 2. Gary et al (2004) | 32 | HF | USA | + | 68 | + | 3 | GDS | + | + | T > UC | ||||

| 3. Gellis and Bruce (2010) | 36 | HF | USA | + | + | 76 | + | 1.5 | BDI, HAM-D | + | + | + | T > UC | ||

| 4. Gellis et al (2012) | 115 | HF | USA | + | + | 79 | + | 3 | PHQ-9, CES-D | + | + | + | T > UC | ||

| 5. Jolly et al (2009) | 169 | HF | UK | + | 68 | + | 6 | SF-36 MH, HADS | + | + | + | T > UC | |||

| 6. Riegel et al (2006) | 134 | HF | US | + | + | 72 | + | 6 | PHQ-9 | + | NS | ||||

| 7. Schwarz et al (2008) | 102 | HF | USA | + | + | 78 | + | 3 | CES-D | + | + | NS | |||

| 8. Tibaldi et al (2009) | 101 | HF | Italy | + | + | 81 | + | <1 | GDS | + | T > UC | ||||

| 9. Witham et al (2005) | 82 | HF | UK | + | + | 80 | + | + | 6 | HADS | + | + | + | NS | |

| 10. Woodend et al (2007) | 249 | HF | Canada | + | + | 66 | + | 3 | SF-36 MH | + | + | T > UC | |||

| 11. Beckie et al (2011) | 252 | CAD | USA | + | 64 | + | 3 | CES-D | + | T > UC | |||||

| 12. Campbell et al (1998) | 1,173 | CAD | UK | + | + | 66 | + | 6 | HADS SF-36 | + | + | + | NS | ||

| 13. Chung et al (2010) | 62 | CAD | Taiwan | + | + | 71 | + | 1 | BDI, PHQ-9 | T > UC | |||||

| 14. Clark et al (2000) | 570 | CAD | USA | + | 72 | + | + | 1 | CES-D | + | + | NS | |||

| 15. Dougherty et al (2004) | 168 | CAD | USA | + | + | 64 | + | 2 | CES-D | + | + | NS | |||

| 16. Norris et al (2009) | 95 | CAD | Canada | + | + | 65 | + | <1 | CES-D | T > UC | |||||

| 17. Rollman et al (2009) | 302 | CAD | USA | + | + | 64 | + | 8 | HAM-D, SF-36 MH | + | + | T > UC | |||

| 18. Seki et al (2003) | 38 | CAD | Japan | + | 70 | + | 6 | SDS | + | + | + | NS | |||

Most studies provided home-based interventions; 3 studies provided outpatient clinic-based interventions and 3 studies carried out combined interventions at the outpatient clinic and in the home. Telehealth care was the most common CR delivery model used followed by exercise strategies. Several trials used collaborative care approaches, whereas others included self-disease management and home-based deep breathing.

A subanalysis resulted in 10 studies reporting samples with a primary diagnosis of HF, whereas 8 studies recruited patients with CAD. Clinical characteristics of patients diagnosed with HF followed by those with CAD are reported.

Patients with HF (n = 1,086, 445 men, 540 experimental subjects, 546 controls) had a mean age of 73 years and a mean CR treatment duration of 3.7 months. Patients with HF were recruited if they met the New York Heart Association class III or IV symptom profile (left ventricular ejection fraction <40%). Thirty-seven percent reported a myocardial infarction in the previous year and 20% reported percutaneous coronary interventions before study enrollment. Most HF studies excluded patients with recent myocardial infarction (<3 months), significant aortic stenosis, sustained ventricular tachycardia, and uncontrolled atrial fibrillation. Common co-morbidities reported at enrollment included hypertension (65%), angina (63%), diabetes (55%), osteoarthritis (54%), and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (30%). Researchers recruited a somewhat diverse older sample consisting of 73% Caucasians, 18% African-Americans, and 9% other. One study recruited a 100% sample of Hispanics. Most study patients were married (53.9%) and reported lower rates of high school completion (38%).

Patients with CAD (n = 2,660, 1,081 men, 1,386 experimental subjects, 1,355 controls) were younger than HF samples with a mean age of 67 years and a mean CR treatment duration of 4.2 months. Similar to the HF studies, 37% of patients with CAD reported a myocardial infarction in the previous year. Twenty-nine percent of patients with CAD reported previous percutaneous coronary interventions. Researchers excluded those with atrial fibrillation, previous cardiac catheterization, and New York Heart Association class III and IV symptoms. Patient co-morbidities included high rates of hyperlipidemia (83%), hypertension (76%), angina (50%), and diabetes (30%). Patients frequently reported a medication regimen of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (39%), β blockers (81%), lipid-lowering drugs (73%), and aspirin (84%). Two studies included 100% Asian patients (Japan, Taiwan) and other study samples recruited approximately 93% Caucasians, 4% African-Americans, and 3% Hispanics. Most patients (60%) reported high school completion.

Across studies, interventionists in the experimental group usually included some combination of trained cardiac nurses, social workers, exercise or physical therapists, and dietitians who followed a CR treatment protocol with cardiologists or primary care physicians as consultants. Study interventionists provided a range of outpatient, telehealth, or telephone-delivered services that included collaborative medical care, nutrition and health education, structured exercise, Tai Chi, motivational interviewing, and/or psychosocial interventions. Usual care providers included nurses, social workers, primary care physicians, and/or cardiologists who delivered standard cardiac care. They provided some combination of outpatient or in-home medical care, heart education, aerobic exercise, nutrition counseling, and/or telephone support.

Figure 2 presents ES estimates of the 15 studies and provides complete data (mean ± SD) to assess the overall impact of CR interventions on depression outcomes. Overall, 11 trials reported significant effects on improvement in depression scores. Of 4 exercise interventions, all but 1 study had positive ESs. One self-disease management intervention had negative effects on depression. The top 3 studies with the largest ESs had relatively small sample sizes ranging from 36 to 115. Average attrition rates of studies with positive ESs and negative ESs were 13.6% and 13%, respectively. Average standardized mean ES of the interventions was 0.18 (95% CI −0.64 to 0.29). ESs ranged from −0.39 (in favor of control group) to 1.09 (in favor of treatment group), and 11 studies showed overall positive ESs on depression outcomes.