Several studies have been conducted to study the efficacy and safety of rivaroxaban in the atrial fibrillation periprocedural ablation period with similar rates of thromboembolism and major bleeding risks compared with warfarin or dabigatran. We sought to systematically review this evidence using pooled data from multiple studies. Studies comparing rivaroxaban with warfarin or dabigatran in patients undergoing catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation were identified through electronic literature searches of MEDLINE, EMBASE, clinicaltrials.gov , and the Cochrane library up to March 2014. Study-specific risk ratios (RRs) were calculated and combined using a random-effects model meta-analysis. In an analysis involving 3,575 patients, thromboembolism (composite of stroke, transient ischemic attack, and systemic and pulmonary emboli) occurred in 3 of 789 patients (0.4%) in the rivaroxaban group and 10 of 2,786 patients (0.4%) in the warfarin group (RR 0.71, 95% CI 0.26 to 1.96, I 2 = 0%, p = 0.51). Major hemorrhage occurred in 9 of 749 patients (1.2%) in the rivaroxaban group and 22 of 975 patients (2.3%) in the warfarin group (RR 0.49, 95% CI 0.24 to 1.02, I 2 = 0%, p = 0.06). Furthermore, direct efficacy and safety comparisons between rivaroxaban and dabigatran showed nonsignificant differences in rates of thromboembolism (0.5% vs 0.4%, respectively, RR 1.12, 95% CI 0.25 to 4.99, I 2 = 0%, p = 0.88) and major bleeding (1.0% vs 1.6%, respectively, RR = 0.71, 95% CI 0.16 to 3.15, I 2 = 22%, p = 0.66). In conclusion, our study suggests that patients treated with rivaroxaban during periprocedural catheter ablation have similar rates of thromboembolic events and major hemorrhage. Similar results were seen in direct comparisons between dabigatran and rivaroxaban.

Radiofrequency catheter ablation (RFCA) for atrial fibrillation (AF) has been an increasingly used procedure for the treatment of patients with symptomatic AF with recurrences despite antiarrhythmic therapy. Periprocedural thromboembolism (TE) is the most feared complication related to RFCA. Continuous warfarin during RFCA of AF has been shown to reduce the risk of TE complications without significantly increasing the risk of major and minor bleeding. However, warfarin takes longer time to reach therapeutic levels can cause an increase the length of hospital stay if adequate anticoagulation is not achieved. Rivaroxaban has the advantage of having a rapid onset and shorter duration of action in this regard. Although rivaroxaban has been shown to be safe and effective for prevention of stroke with similar rates of bleeding compared with warfarin in patients with AF, its safety and efficacy during RFCA for AF has not been established. A few smaller studies have been done that showed similar safety and efficacy of rivaroxaban compared with warfarin or dabigatran. The purpose of this study was to systematically review the existing efficacy and safety data for use of rivaroxaban in patients undergoing catheter ablation. Furthermore, we aimed to directly compare these outcomes between rivaroxaban and dabigatran because pooled studies using dabigatran in the previous meta-analyses have been compared with warfarin and have shown that dabigatran appears to be a safe alternative agent.

Methods

The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews as recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration was used for this systematic review. This qualitative systematic review included studies published up to March 2014. Searches of MEDLINE, Cochrane Library, EMBASE, and clinicaltrials.gov were carried out to identify eligible studies. These databases were searched using the search terms under 2 broad search themes and combined using the Boolean operator “AND” (refer to Supplementary File 1 for search strategy). For the theme “rivaroxaban,” we used a combination of MeSH, entry terms, and text words rivaroxaban and factor Xa inhibitor. For the theme “atrial fibrillation,” atrial fibrillation and auricular fibrillation were used. For the theme “catheter ablation,” catheter ablation, ablation, radiofrequency catheter ablation, radiofrequency ablation, electrical catheter ablation, electrical ablation, electric catheter ablation, electric ablation, transvenous electric ablation, transvenous electrical ablation, percutaneous catheter ablation, and transvenous catheter ablation were used.

All clinical trial results, including case-control, observational studies, randomized controlled trial (RCT), and meta-analyses of clinical trials, were reviewed. No language restriction was used. Bibliographies belonging to included articles, known reviews, and relevant articles were reviewed to identify additional trials. To minimize data duplication as a result of multiple reporting, we compared articles from the same investigator. Two investigators (AU and PK) screened and retrieved reports and excluded irrelevant studies. Relevant data were extracted by 2 investigators (AU and PK) and checked by another (MRA). Additional investigator (RP) participated in the review process when uncertainty about eligibility criteria arose. In case of missing data, the senior investigators of the included studies were contacted for the unpublished data. From each study, we extracted and tabulated details on study source type, design, patients with paroxysmal AF, mean age in years, percentage of female patients, estimated TE risk, estimated bleeding risk, left ventricular ejection fraction, and kidney function ( Supplementary Table 1 ). Furthermore, the details on procedure including dosing regimen, timing of restarting and holding the anticoagulants, periprocedural bridging regimen, left atrial appendage evaluation, target activated clotting time, and follow-up duration were extracted ( Supplementary Table 2 ). End points across the studies were also listed ( Supplementary Table 3 ).

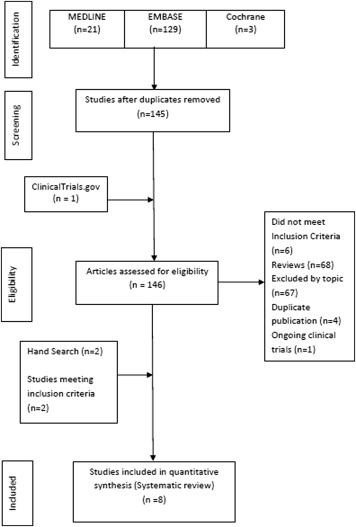

Selected studies included all observational (case-control and cohort) studies and RCTs that compared the use of rivaroxaban with warfarin or dabigatran. The steps of the literature search process are summarized in Figure 1 . Published full-text articles or conference articles were included for this study. The eligibility criteria for this systematic review were (1) human subjects with a diagnosis of AF undergoing RFCA; (2) reported periprocedural outcomes comparing rivaroxaban, uninterrupted rivaroxaban, or bridged with low–molecular weight heparin (LMWH) or unfractionated heparin (UFH) (intervention) with warfarin (uninterrupted warfarin or bridged with LMWH or UFH) or dabigatran (uninterrupted or bridged); and (3) minimum reported data until discharge after the procedure. Studies without documented therapeutic anticoagulation in the 3 weeks preceding AF ablation, studies not reporting of desired outcomes with their definitions (TE phenomenon, major bleed and minor bleed), and lack of use of vitamin K antagonist (VKA)/dabigatran as a comparator were excluded from our analysis. In addition, studies that did not demonstrate use of rivaroxaban or dabigatran 1 month before and after ablation were excluded. Finally, studies not reporting outcomes separately during RFCA were also excluded from our analysis. It was impossible to extract and determine the outcomes from the post hoc analysis of Rivaroxaban Once Daily Oral Direct Factor Xa Inhibition Compared with Vitamin K Antagonism for Prevention of Stroke and Embolism Trial in Atrial Fibrillation (ROCKET AF) trial after RFCA alone for rivaroxaban independent of cardioversion and hence was not included in our analysis. A total of 8 studies were included for analysis. Three included studies were conference abstracts. One study, an RCT, had direct comparison of dabigatran and rivaroxaban. This study was used while making comparison for dabigatran and rivaroxaban.

Study quality was formally evaluated by 2 investigators (AD and AU) using a modified Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale for Case Control Studies and Delphi consensus criteria for RCT. Any discrepancies were resolved by a third author (PK) ( Supplementary Table 4 ).

Three outcomes were assessed during the periprocedural period. (1) Efficacy was assessed by TE phenomenon (composite of stroke, transient ischemic attack, and systemic or pulmonary embolism) in the periprocedural period (during index hospitalization or within 1 week of hospitalization). Ischemic stroke was defined as sudden onset of a focal neurologic deficit in a location consistent with the territory of a major cerebral artery. Outcomes as positive imaging findings on magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomography with no clinical symptoms were excluded for analysis. (2) For our safety outcome, major bleeding was reported (composite of bleeding requiring intervention or transfusion, cardiac tamponade, or pericardial effusion requiring drainage, retroperitoneal bleeding, massive hemoptysis, hemothorax, and bleeding requiring extra hospital stay). (3) Minor bleeding, defined as by gastrointestinal bleeding, puncture site bleeding, thigh ecchymosis, hematoma, pericardial effusion, epistaxis, or with no intervention or without transfusion was taken as a secondary end point. Although minor bleeding was reported in multiple studies, it was not taken into consideration for our primary safety outcome. One-month follow-up outcomes were also analyzed when available.

Outcomes from the individual studies were calculated with RevMan, version 5.2, for Mac (Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, United Kingdom). A formal systematic review was performed applying the Mantel-Haenszel test using the software. Risk ratios (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated using a random-effects method to control the heterogeneity as their assumption accounts for the presence of variability among the studies. Fixed effect was used if I 2 was 0%. I 2 statistics to evaluate the percentage of heterogeneity among the studies were also calculated. I 2 values <30% were considered as low heterogeneity, 30% to 60% as moderate, and >60% as high. A p value of <0.05 was used as the level of significance. Publication bias was assessed by review of a funnel plot ( Supplementary Figure 1 ). Sensitivity analyses were conducted withdrawing the lone RCT. Further sensitivity analysis was carried out including studies that held >2 doses of rivaroxaban, dabigatran, or VKA; studies that had follow-up for 30 days’ period; studies in which patients were treated with uninterrupted VKA; studies without periprocedural bridging with UFH or LMWH; and investigations published as full-text articles and higher quality studies (Delphi criteria ≥5 and RCT).

Results

Although the 8 studies tried to assess similar efficacy end points and outcomes, they were slightly different in terms of overall design and outcome definitions (baseline characteristics of the included studies, Supplementary Table 1 ; periprocedural details, Supplementary Table 2 ; and comparison of end points across the studies, Supplementary Table 3 ). There were a total of 3,575 patients analyzed for TE events, 1,699 for major bleeding, and 1,479 for minor bleeding for comparison between rivaroxaban and VKA. Similarly, there were a total of 1,439 patients analyzed for TE events and 895 patients for major bleeding when comparing rivaroxaban and dabigatran. Most of the studies were single-center observational studies except the studies by Lakkireddy et al (multicenter observational) and Murakawa et al (national registry). Most studies held 1 to 2 doses of rivaroxaban before the procedure. The activated clotting time reported was from 300 to 450 seconds in most studies. Doses of either 15 or 20 mg of rivaroxaban were used. In all studies, warfarin was used as a VKA except in the study by Providência et al in which the VKA consisted of fluindione, warfarin, or acecumarol. The European Society of Cardiology 2012 updated guidelines for recommended VKAs but not any specific subtype allowing the use of these drugs in the country of study. Hence, we included all VKAs for our analysis. The study by Sairaku et al compared dabigatran and rivaroxaban; hence, it was included in head-to-head comparison of dabigatran and rivaroxaban analysis. Because Stepanyan et al did not report pericardial effusion that occurred separately in 2 different anticoagulants (VKA or dabigatran), total pericardial effusion events were taken as a major bleeding complication.

In 7 studies involving 3,575 patients, TE occurred in 3 of 789 patients (0.4%) in the rivaroxaban group and 10 of 2,786 patients (0.4%) in the VKA group (RR 0.71, 95% CI 0.26 to 1.96, Z = 0.66, p = 0.51, I 2 = 0%; Figure 2 ). In 6 studies involving 1,724 patients, the incidence of major hemorrhage was observed in 9 of 749 patients (1.2%) in the rivaroxaban group and in 22 of 975 patients (2.3%) in the warfarin group (RR 0.49, 95% CI 0.24 to 1.02, Z = 1.92, p = 0.06, I 2 = 0%; Figure 2 ). In 4 studies involving 1,479 patients, the incidence of minor hemorrhage was observed in 25 of 638 patients (1.5%) in the rivaroxaban group and in 41 of 841 patients (2.1%) in the warfarin group (RR 0.92, 95% CI 0.57 to 1.50, Z = 0.33, p = 0.74, I 2 = 0%; Supplementary Figure 2 ). In 6 studies involving 1,439 patients, TE occurred in 2 of 444 patients (0.5%) in the rivaroxaban group and 4 of 995 patients (0.4%) in the dabigatran group (RR 1.12, 95% CI 0.25 to 4.99, Z = 0.15, p = 0.88, I 2 = 0%; Figure 3 ). In 5 studies involving 895 patients, the incidence of major hemorrhage was observed in 4 of 404 patients (1.0%) in the rivaroxaban group and in 8 of 491 patients (1.6%) in the dabigatran group (RR 0.71, 95% CI 0.16 to 3.15, Z = 0.44, p = 0.66, I 2 = 22%; Figure 3 ). An outcome table summarizing the results is also provided ( Supplementary Table 5 ).