Classification of vasculitis

Large-vessel vasculitis

Takayasu arteritis

Giant cell arteritis

Medium-sized-vessel vasculitis

Poliarteritis nodosa

Kawasaki disease

Primary granulomatous central nervous system vasculitis

Small-vessel vasculitis

Antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody

Wegener’s granulomatosis

Churg-Strauss syndrome

Microscopic angiitis

Immune complex small-vessel vasculitis

Henoch-Schonlein purpura

Cryoglobulinemic vasculitis

Lupus vasculitis

Rheumatoid vasculitis

Sjogren syndrome vasculitis

Hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis

Behoet’s syndrome

Goodpasture’s syndrome

Serum sickness vasculitis

Inflammatory bowel disease vasculitis

Large-vessel vasculitis affects the aorta and its branches, medium-size vessel vasculitis has a predilection for the visceral arteries, and small-vessel vasculitis affects arterioles, venules, and capillaries. Although vasculitis of the mesenteric arteries is rare, accounting for less than 5 % of all cases of mesenteric ischemia [2], it can lead to bowel gangrene and death if not immediately recognized and treated. This chapter summarizes the clinical features, diagnostic approaches and treatment of mesenteric vasculitis (MV).

Clinical Presentation

MV usually presents with bleeding or ischemic symptoms. Upper and lower gastrointestinal bleeding is the most common presentation and is associated with mucosal lesions or rupture of small branch artery aneurysms. Mesenteric ischemia presents with symptoms that are indistinguishable from those of atherosclerotic or embolic origin. The classic symptoms include abdominal pain, postprandial pain, “food fear,” and weight loss. In patients with medium-size vessel vasculitis, such as polyarteritis nodosa (PAN), inflammation may lead to aneurysm formation and vessel rupture with either intra-abdominal or gastrointestinal hemorrhage. If the smaller arteries are involved, ulceration, perforation, and stricture formation can occur. In addition to bleeding and ischemic symptoms, patients often manifest other constitutional symptoms such as weight loss, malaise, fever, night sweats, arthralgias, myalgia, peripheral weakness, and headache.

Diagnostic Imaging

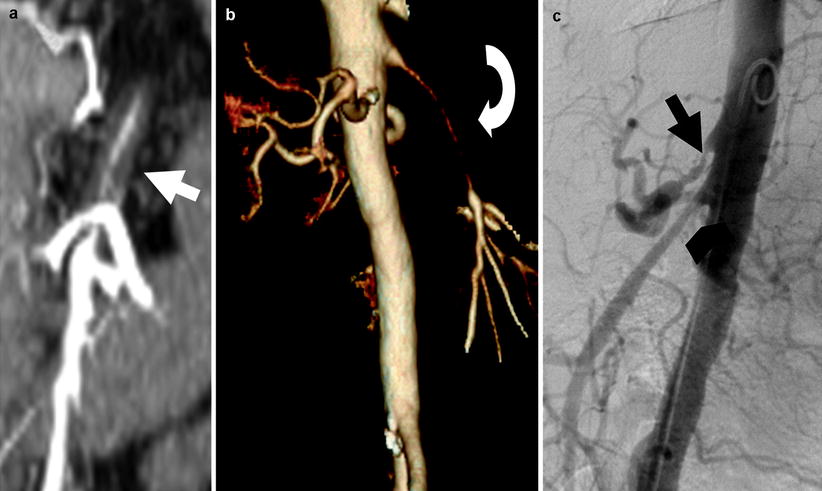

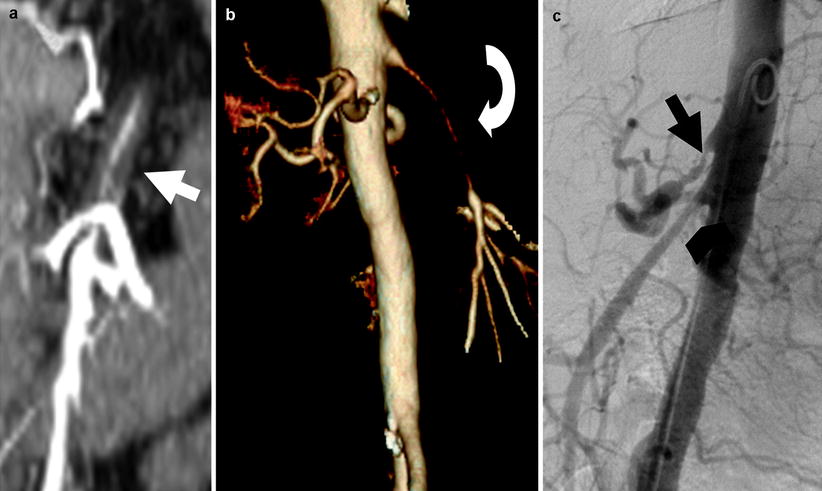

Duplex ultrasound is used to screen test and evaluate patency of the visceral arteries and presence of hemodynamically significant stenoses or occlusions. The criteria to identify a high-grade stenosis include peak systolic velocity >275 cm/s for the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) and >200 cm/s for the celiac axis [11]. Selective mesenteric angiography remains the gold standard for diagnosis of mesenteric vasculitis. The classic finding includes long, tapered, smooth lesions without stigmata of atherosclerosis, such as calcifications or atheromatous plaque (Fig. 24.1). Multiple and small aneurysms are also frequently seem. Barium enema may show thumbprinting due to submucosal edema or hemorrhage. Computed tomography angiography (CTA) is an excellent imaging study to diagnose and plan the intervention. It allows greater spatial resolution and is useful to diagnose other potential causes of abdominal pain and weight loss (e.g., malignancy). Specific findings consistent with mesenteric vasculitis include vessel wall thickening, periarterial edema or stranding, and long, smooth lesions with or without concomitant aneurysms or pseudoaneurysms (Fig. 24.1). This study is useful to plan open surgical reconstruction, allowing selection of a diseased-free site for inflow and outflow of bypass procedures. In addition, evaluation of bowel wall thickening (e.g., the target sign), increased attenuation of mesenteric fat, pneumatosis intestinalis, or pneumoperitoneum is consistent with complicated acute ischemia, bowel gangrene, and perforation.

Fig. 24.1

Imaging findings consistent with mesenteric vasculitis includes arterial wall thickening (a, white arrow) and long and smooth tapered lesions (b, curved white arrow). Angiography remains the gold standard diagnostic study. Panel c shows a lateral aortography with high-grade celiac (c, straight black arrow) and superior mesenteric artery stenoses (c, black arrowhead)

Specific Disorders

A variant of specific vasculitis can manifest with symptoms of mesenteric ischemia or bleeding complications (Table 24.2).

Table 24.2

Differential diagnosis of mesenteric ischemia

Arterial Occlusion | Venous Occlusion | Non-Occlusive Disease |

Thromboembolism | Venous thrombosis | Narcotics |

Left atrial origin | Infiltrative conditions | Cocaine |

Aortic origin | Neoplasm | Heroin |

Myxoma | Inflammatory conditions | Shock Bowel |

Endocarditis | Abdominal infectious diseases | Familial dysautomia |

Cholesterol | Hypercoagulable conditions | Pheochromocytoma |

Atherosclerosis | Polycitemia vera | High-endurance athletes |

SMA thrombosis | Sickle cell disease | Chronic renal failure |

Arterial dissection | Thrombocytosis | Trauma |

Aortic surgery | Thrombophilia | Corrosive injury |

Stent placement | Carcinoma | |

Therapeutic embolization | Pregnancy drugs | |

Antiphospholipid antibody syndrome | Systemic vasculitis | Iatrogenic |

Systemic vasculitis | Wegener’s granulomatosis | Radiation |

Takayasu’s arteritis | Systemic lupus erytematous | Prostraglandins antagonist Immunotherapy |

Giant cell arteritis | Behçet’s syndrome | Chemotherapy |

Polyarteritis nodosa | Complicated bowel obstruction | Vasoconstriction |

Systemic lupus erytematous | Strangulated hernia | Digitalis |

Henoch-Shonlein purpura | Strangulated closed loop obstruction | Ergotamine |

Wegener’s granulomatosis | Volvulus | Vasopressin |

Churg-Strauss syndrome | Intussusception | Epinephrine |

Thromboangiitis obliterans | Intestinal overdistention | Hypotension |

Rheumatoid vasculitis | Enterocolic lymphocitic phlebitis | Diuretics |

Behçet’s syndrome | Antidepressants < div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|