Mediastinal Nerve Sheath Tumors (Schwannoma, Neurofibroma, Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumor)

Borislav A. Alexiev, M.D.

Jennifer M. Boland, M.D.

General

Peripheral nerve sheath tumors encompass a spectrum of well-defined clinicopathologic entities, ranging from benign tumors, including schwannoma, neurofibroma, and perineurioma, to high-grade malignant neoplasms termed malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (MPNSTs).1 Perineuriomas, which express epithelial membrane antigen and possess wavy nuclei and slender, bipolar cytoplasmic processes, have rarely if ever been described in the mediastinum and will not be discussed further.2

Neural tumors constitute about 15% of mediastinal tumors in adults and are usually in the posterior mediastinum. Two-thirds are schwannomas, and the majority of the remainder are ganglioneuromas.3 Ganglioneuromas and tumors with neuroblastic differentiation are discussed in Chapter 135.

Most benign peripheral nerves sheath tumors are sporadic, although multiple neurofibromas suggest neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1 or von Recklinghausen disease) and multiple schwannomas suggest neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2) or schwannomatosis. MPNSTs are rare; ˜50% are NF1 associated, 10% are associated with prior therapeutic irradiation, and the remainder are sporadic.4

Schwannoma

Terminology

Schwannoma, also termed neurilemmoma, is a benign nerve sheath tumor arising from Schwann cells.

Incidence and Clinical Findings

Schwannoma is the most common neurogenic tumor of the mediastinum and may involve any thoracic nerve.5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12 The vast majority originate in the posterior mediastinum, while anterior and middle mediastinal schwannomas are rare.4,10 Approximately 10% of mediastinal schwannomas originate from the vagus nerve, and are almost twice as likely to be located on the left as on the right.11

Mediastinal schwannomas occur at all ages and may show a female predilection.4 Almost two-thirds are incidental findings on imaging studies performed for other reasons. Presenting symptoms in the other third include shoulder, flank, back, or chest pain; symptoms of Horner syndrome; dysphagia; cough; and palpitations. Most patients do not have a clinical syndrome such as NF2, although there may be a history of sporadic schwannomatosis or familial adenomatous polyposis.4 Mediastinal schwannomas may mimic pericardial or bronchogenic cysts, if cystic degeneration is extensive.4,13

Plexiform and melanotic schwannomas are two distinctive subtypes that are variably associated with schwannoma predisposition syndromes, including NF2 and schwannomatosis, or Carney complex, respectively.14 Multiple schwannomas in a patient without café au lait spots, characteristic of NF1, are often seen in NF2.15 Plexiform schwannomas have rarely been reported in the mediastinum as an extension of a neck tumor,16 and melanotic schwannomas have also rarely been reported in the mediastinum.17

Schwannomas very rarely undergo malignant change, most often in the form of epithelioid MPNST.18

Gross Pathology

The gross appearance of schwannomas is an encapsulated, round-toovoid, firm mass with cystic change. Lesions affecting spinal nerve roots are often dumbbell shaped. Sectioned tumors reveal firm or rubbery, light tan (conventional schwannoma) to gray-black (melanocytic schwannoma) glistening tissue, with patchy hemorrhage.

Microscopic Pathology

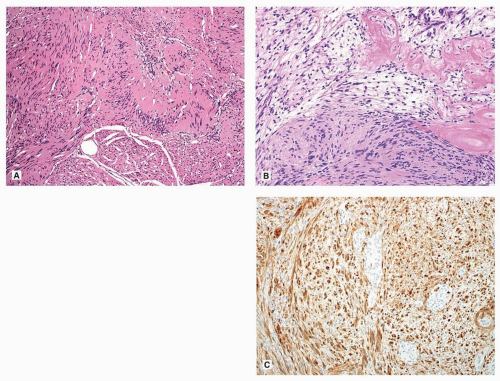

Conventional schwannomas are encapsulated biphasic tumors composed of compact hypercellular Antoni A areas and myxoid hypocellular Antoni B areas that resemble neurofibroma. Antoni B areas may be absent in small tumors or cellular schwannomas. The cells are narrow, elongate, and wavy with tapered ends interspersed with collagen fibers. Tumor cells have ill-defined cytoplasm and dense chromatin. Nuclear palisading around fibrillary process (Verocay bodies) is often seen in Antoni A areas (Fig. 134.1A). Schwannomas have characteristic irregularly spaced gaping tortuous vessels with thickened hyalinized walls (Fig. 134.1B). The tumors often display degenerative nuclear atypia (ancient change). Mitoses are rarely observed. Rare findings in schwannomas include large cellular palisades resembling neuroblastic rosettes (i.e., “neuroblastoma-like” schwannoma), pseudoglandular structures, benign epithelioid change, and lipoblastic differentiation.1

Cellular schwannoma, although relatively uncommon, is an important variant of schwannoma to recognize, because its high cellularity, fascicular growth pattern, increased mitotic activity, and occasional locally destructive behavior (including bone erosion) often prompt consideration of malignancy. Cellular schwannoma is defined as a schwannoma composed almost entirely of a compact, fascicular proliferation of well-differentiated, cytologically bland cells lacking Verocay bodies and showing no more than very focal Antoni B pattern growth. Important clues to this diagnosis include the presence of foamy histiocyte aggregates, the typical hyalinized vascular pattern of schwannoma, and a well-formed capsule containing lymphoid aggregates.

Plexiform schwannoma is a distinctive subtype of schwannoma that rarely occurs in the mediastinum and is defined by a plexiform (intraneural-nodular) pattern of growth.1,19 Characteristic histologic features included hypercellularity, composed of spindled cells with elongate hyperchromatic nuclei, and indistinct cellular outlines. The nuclei vary minimally in size and shape but are at least three times the size of typical neurofibroma nuclei. Mitoses are frequently seen. Plexiform tumors differ from conventional schwannomas and nonplexiform cellular schwannomas by their lack of both well-formed capsules and degenerative changes.

Melanotic schwannoma is a rare, distinctive, potentially malignant neoplasm characterized by spindled or epithelioid cells with variably sized nuclei, small distinct nucleoli, marked accumulation of melanin in neoplastic cells, and associated melanophages.14,20 One of 13 in one series was present in the mediastinum.17 In some areas, the nucleoli may be large and prominent. The presence of psammoma bodies in these tumors (i.e., psammomatous melanotic schwannoma) is associated in approximately half the cases with Carney complex.1

Special Studies

By immunohistochemistry, schwannomas characteristically show diffuse, strong expression of S100 protein (Fig. 134.1C) and abundant pericellular laminin and collagen type IV, consistent with the presence of a continuous pericellular basal lamina. Glial fibrillary acid protein (GFAP) is expressed in a subset of schwannomas. Recently described markers frequently positive in schwannomas include SOX10, which is a nuclear marker that can be diagnostically useful in evaluation of schwannian and melanocytic tumors, as well as more nonspecific markers podoplanin and calretinin.1

In melanocytic schwannomas, the pigment is positive for Fontana-Masson and negative for Prussian blue and PAS. Melanocytic schwannomas strongly express various schwannian, melanocytic, and basement membrane markers, including but not limited to S100, HMB-45, Melan-A, vimentin, laminin, and collagen IV.14,20 Ultrastructurally, numerous elongated tumor-cell processes, duplicated basement membrane, and melanosomes are observed in all developmental stages.1 Gene expression profiling shows significant differences between melanotic schwannoma, melanoma, and conventional schwannoma. Loss of PRKAR1A expression suggests a link to Carney complex in patients with melanotic schwannoma, even when this history is absent.14,20

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of schwannoma depends on the morphology of the tumor, and may include other benign and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors, as well as other S100-positive neoplasms, specifically melanoma. It may be difficult to distinguish schwannoma from neurofibroma on small biopsies, since the Antoni B areas of schwannoma can be indistinguishable from neurofibroma histologically. Since this is typically not a critical distinction on a small biopsy, a diagnosis of benign peripheral nerve sheath tumor is usually adequate, and definitive subtyping can be performed if the tumor should be excised. Concern for malignancy may arise in cellular schwannomas. Diffuse S100 protein expression is exceedingly uncommon in spindled MPNST, and this finding should always raise the possibility of cellular schwannoma. Combined use of laminin and collagen IV is often helpful in distinguishing melanotic schwannoma from malignant melanoma.1

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree