Fig. 5.1.

Medial view of the left hemithorax. Used with permission from the McGill University Health Centre Patient Education Office.

Fig. 5.2.

Medial view of the right hemithorax. Used with permission from the McGill University Health Centre Patient Education Office.

Table 5.1.

Differential diagnosis of a mediastinal mass based on compartment.

Anterosuperior compartment | Middle compartment | ||

|---|---|---|---|

Thymus | Thymic hyperplasia | Lymph node | See anterosuperior compartment |

Thymoma | Cyst | Bronchial cyst | |

Thymic carcinoma | Pericardial cyst | ||

Carcinoid tumor | Enteric (duplication) cyst | ||

Small-cell carcinoma | Esophagus | See posterior compartment | |

Thymolipoma | Posterior compartment | ||

Thymic cyst | Neurogenic | Schwannoma | |

Germ cell | Teratoma | Neurofibroma | |

Dermoid cyst | Ganglioneuroma | ||

Seminoma | Ganglioneuroblastoma | ||

Choriocarcinoma | Neuroblastoma | ||

Embryonal cell carcinoma | Esophagus | Duplication cyst | |

Yolk sac tumor | Diverticulum | ||

Lymph node | Inflammatory | Benign tumor | |

Infectious | Malignant tumor | ||

Malignant (metastasis) | Other | Meningocele | |

Lymphoproliferative disorder | Paraganglioma | ||

(e.g., lymphoma) | |||

Mesenchymal | Fibroma/fibrosarcoma | ||

Lipoma/liposarcoma | |||

Lymphangioma | |||

Hemangioma | |||

Endocrine | Thyroid | ||

Parathyroid | |||

Vascular | Aneurysm | ||

Anterior Compartment: anterior to pericardium and reflection over the great vessels.

Includes: thymus gland, lymph nodes, fat

In adults, approximately 50 % of mediastinal masses are located in the anterosuperior compartment

>90 % consist of thymomas, ectopic thyroid tissue, germ cell tumors, or lymphomas

Middle Compartment: bound by anterior and posterior edges of the pericardium

Includes: heart, pericardium, ascending and transverse aorta, brachiocephalic vessels, vena cavae, pulmonary arteries and veins, phrenic and vagus nerves, trachea, bronchi, and lymph nodes

Posterior Compartment: posterior to pericardium, heart, and trachea and extends to the thoracic vertebral column and paravertebral gutters

Includes: esophagus, descending aorta, azygos and hemiazygos veins, thoracic duct, sympathetic chain, and lymph nodes

Clinical Presentation (Table 5.2):

Table 5.2.

Clinical presentation of a patient with a mediastinal mass.

Locoregional symptoms | Systemic symptoms | ||

|---|---|---|---|

Somatic | Chest pain | Constitutional Symptoms | Night sweats |

Pulmonary | Cough | Fatigue | |

Wheezing | Weight loss | ||

Stridor | Pel–Ebstein fevers | ||

Dyspnea | Systemic | Thyrotoxicosis | |

Hemoptysis | Syndromes | Hypercalcemia | |

Post-obstructive pneumonitis | Hypoglycemia | ||

Recurrent pneumonia | Osteoarthropathy | ||

Cardiovascular | Superior vena cava syndrome | Autoimmune syndrome | |

Pericardial tamponade | Paraneoplastic syndrome | ||

Congestive heart failure | Yolk sac (endodermal cell) tumor | ||

Neurogenic | Hoarseness | ||

Horner’s syndrome | |||

Phrenic nerve paralysis | |||

Brachial plexopathy | |||

Majority are asymptomatic and discovered incidentally (especially benign lesions)

Symptomatology related to local mass effect, invasion of surrounding structures, and immunologic and hormonal factors related to the lesion. Systemic symptoms (e.g., Type B symptoms) are also seen in lymphoma.

Physical examination: a full head-to-toe examination, including peripheral lymph nodes and testes in men.

Diagnosis made by considering the patient’s age, location of the mass, presence or absence of locoregional and distant clinical manifestations:

Workup

Laboratory: full blood panel, including thyroid function tests, tumor markers (α-fetoprotein (AFP), β-human Chorionic Gonadotropin (βhCG)), cardiac enzymes for chest pain, and autoantibody assays for suspected autoimmune syndromes.

Imaging:

Contrast enhanced CT is the modality of choice for detailed characterization of the mass (Fig. 5.3).

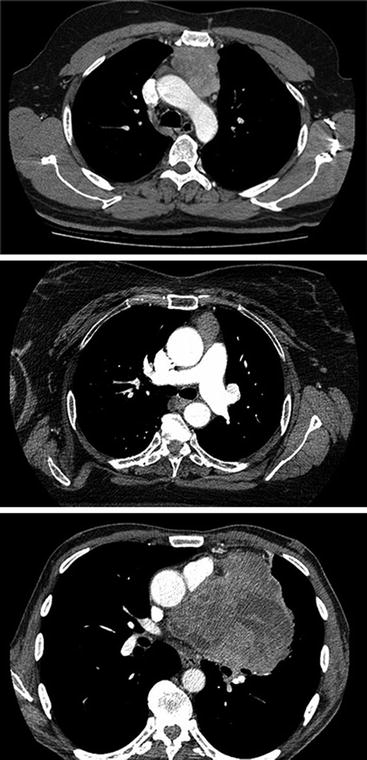

Fig. 5.3.

Axial cuts from contrast enhanced CT scan of thymoma in the anterior compartment of the mediastinum.

MRI used as an adjunct to provide additional information about the tissue planes and margins, as well as to differentiate between tumor compression and invasion of surrounding structures.

FDG-PET:

Tissue diagnosis:

Routine needle biopsy (FNA and core-needle) is typically avoided and the choice of resection or biopsy is made according to the most likely diagnosis based on workup.

If lymphoma is suspected, biopsy is required.

Well-encapsulated lesions unlikely to be lymphoma can be directly resected.

Locally invasive and unresectable lesions (other than lymphoma) are typically biopsied and evaluated for possible neoadjuvant therapy (e.g., thymic carcinoma).

Complications of biopsy include: pneumothorax (20–25 %), hemoptysis (5–10 %), significant hemorrhage (rare), and tumor seeding along needle tract (extremely rare).

Incisional and excisional biopsies may also be performed under general anesthesia. This may not be possible for patients with high risk of cardiopulmonary compromise (e.g., posture-related dyspnea, SVC syndrome). Options include:

Mediastinoscopic biopsy

2nd/3rd intercostal space parasternal mediastinotomy (Chamberlain procedure)

Transcervical approach

VATS

Thymoma

Overview

Most common neoplasm of the anterosuperior compartment in adults.

Slow-growing epithelial tumor that spreads by local invasion. Extra-thoracic metastases are uncommon [7]

Pathology

Controversial distinction between thymomas and thymic carcinomas (Table 5.3).

Table 5.3.

Classification of mediastinal masses originating from the thymus.

Thymus hyperplasia

Epithelial neoplasms

Thymoma

Thymic carcinoma

Thymic neuroendocrine tumors

– Carcinoid tumor

– Small-cell carcinoma

Thymolipoma

Thymic cyst

WHO Classification (Table 5.4) stratifies them along a continuum [8].

WHO classification

Epithelial cell shape

Epithelial cell atypia

Lymphocyte

Organotypic “(Thymus-like)”

Incidence (%) [29]

A

Spindle

Minimal

Poor

Yes

9

AB

Spindle/polygonal

Minimal

Moderate

Yes

24

B1

Polygonal

Minimal

Abundant

Yes

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access