Chapter 9

Measurement of breathlessness

Mark B. Parshall1 and Janelle Yorke2

1College of Nursing, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM, USA. 2University of Manchester and The Christie NHS Foundation Trust, Manchester, UK.

Correspondence: Mark B. Parshall, College of Nursing, MSC07 4380, Box 9, 1 University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM 87131-0001, USA. E-mail: MParshall@salud.unm.edu

There are many measurement approaches and instruments for assessing the sensory-perceptual experience of breathlessness, the associated affective distress and how breathlessness impacts an individual’s functioning and quality of life. Choices of which measures to use should be driven by the relevance of the measured construct(s) to the context(s) of use, and, in palliative care, by the responsiveness of measures to clinical change and by their ease of administration and scoring. Evidence of adequate psychometric performance characteristics can be viewed as necessary but not sufficient for preferring one measurement approach or instrument to another in palliative care.

Guidelines for research with and care of patients with advanced cardiopulmonary disease [1–6] or palliative care [7–10] generally recommend routine measurement of patient-reported outcomes, particularly breathlessness and its impact on quality of life (QoL) [1–4, 11–14]. When it is feasible to do so, breathlessness should be measured by self-report [11, 14, 15]. Poor agreement between breathlessness ratings of patients, physicians and nurses has been reported in mechanically ventilated patients undergoing spontaneous breathing trials [16]. In palliative care, agreement between health professionals and patients is stronger for the presence of breathlessness than for its severity [17]. Self-report is preferred for QoL measurement, but proxy estimation by family members can be reliable in situations in which self-report is infeasible or would be excessively burdensome for the patient.

Many instruments have been developed for measuring various aspects of breathlessness [3, 11, 13, 18, 19]. Relatively few have been rigorously evaluated for research [13] or clinical use [10] in palliative care settings where, ideally, breathlessness measures should be simple to administer, responsive to clinical change, and relevant across diagnoses and contexts of care [8, 15, 20]. QoL has always been an overarching concern in palliative care, and in this context, the focus for measurement of breathlessness is often the impact of the symptom on functioning, daily activities and QoL, rather than how breathing feels. It is also common for ratings of breathlessness to be embedded in an inventory of QoL concerns or multiple symptoms (such as pain or fatigue) [21–27]. However, as disease becomes more advanced and the focus of care is on EOL, scales that require linking breathlessness to usual activities become less appropriate and useful.

The multidimensional nature of breathlessness is emphasised in conceptual models of the symptom [9, 15, 28–32] and in frameworks and models for its measurement [11, 33–37]. According to a framework proposed by the American Thoracic Society [11], measures of breathlessness can be categorised as pertaining to domains of sensory-perceptual experience (what breathing feels like), affective distress (how unpleasant or distressing it is or how it makes one feel), or symptom impact or burden (how it affects QoL and psychosocial or physical functioning). The domains are not mutually exclusive, and many measures tap into more than one domain. Conceptual clarity about measurement domains and their potential relevance to clinical or research purposes should guide the choice and timing of measurement approaches. In clinical palliative care, there is a close correspondence between these measurement domains and “operational levels in the experience of breathlessness” proposed by RYAN et al. [29]: breathlessness perception, emotional–behavioural response and functional impact. The choice of measures can be guided by which of these levels is of greatest concern to the patient [15].

Several systematic reviews focused on measurement of breathlessness or QoL in advanced disease have been published [18, 19, 38, 39]. For this chapter, multiple PubMed searches were conducted using combinations of the search terms shown in table 1, plus names and acronyms of various instruments. Choices of which measures to include in this chapter were based on considerations such as ease of use, responsiveness, relevance across diagnoses and availability of published data on use in palliative care.

Table 1. Search terms used in PubMed

(“dyspnea”[All Fields] OR “dyspnoea”[All Fields] OR “breathlessness”[All Fields]) |

AND |

(“surveys and questionnaires”[MeSH Terms] OR “reproducibility of results”[MeSH Terms] OR “psychometrics”[MeSH Terms] OR “questionnaire”[All Fields] OR “psychometrics”[All Fields] OR “psychometric”[All Fields] OR “patient reported outcome”[All Fields] OR “reliability”[All Fields]) |

AND |

(“pulmonary disease, chronic obstructive”[MeSH Terms] OR “COPD”[All Fields] OR “COPD”[All Fields] OR “heart failure”[MeSH Terms] OR “heart failure”[All Fields] OR “neoplasms”[MeSH Terms] OR “cancer”[All Fields]) |

AND |

(“palliative care” [MeSH Terms] OR “palliative care”[All Fields] OR “advanced disease”[TIAB] OR “advanced disease”[TW]) |

Measuring sensory-perceptual and affective distress domains of breathlessness

Breathlessness measures can be single-item ratings or multi-item scales that can be either unidimensional or multidimensional. Measured aspects of breathlessness include: intensity of overall breathing discomfort or unpleasantness; severity of overall or breathlessness-related distress; presence/absence or intensity of various sensory qualities (e.g. effort, air hunger, tightness); frequency of episodes of breathlessness or of related distress or impairment; or the extent of activity limitation or level of task or activity at which breathlessness typically occurs. Time frames commonly include: right now or some recent point in time (e.g. last minute of an exercise stimulus; when someone sought unscheduled care), elapsed time (e.g. last week or month; worst episode in past 24 h), how things usually are, or the time of day when breathlessness episodes typically occur.

Unidimensional measures

Self-report scales

Single-item ratings of breathlessness include VASs or NRSs [40–42] and the modified Borg category-ratio scale [43, 44]. Given their relative ease of completion and the fact that they are not necessarily linked to an activity, such scales can be useful in the palliative care setting. Breathlessness can be quantified by asking the patient and/or carer to point to or say the number reflecting their shortness of breath. No compelling evidence exists to indicate superiority of any of these scale types over any other; rather, one or another may be preferred according to practical or contextual considerations (table 2). For example, the modified Borg scale was derived from an earlier Rating of Perceived Exertion [53], and is often preferred by researchers using cardiopulmonary exercise testing as a stimulus for eliciting breathlessness [32]. However, in relatively uncontrolled clinical settings, some evidence indicates that patients may be less likely to choose modified Borg numerical ratings that are not coupled with categorical labels (i.e. 6 or 8) [49], which may make it less useful in a palliative care setting compared with an NRS. Minimum clinically important differences (MCIDs; i.e. the threshold score difference that patients associate with beneficial change) are similar for the modified Borg scale and NRS for breathlessness (approximately 1 point in both cases [45, 46, 54]) and proportionate for the VAS (∼10–12 mm for a moderate effect size [46, 47] or relative 10% change [48]). In a distribution-based secondary analysis of VAS breathlessness ratings from clinical trials of opioids for refractory, chronic breathlessness, decreases of 5.5 mm, 11.3 mm and 18.2 mm corresponded to standardised effect sizes of 0.25, 0.5 and 0.8 SD, respectively, and an anchor-based decrease of 9 mm was identified as clinically meaningful in relation to masked preference ratings from participants [47].

In clinical practice, if only a single rating is used, it may not matter whether the anchor statements emphasise the intensity of sensation (e.g. “maximum breathlessness”) or affect (e.g. “unbearable”), as long as the rating and instructions are consistent across administrations. Evidence from pain research shows that patients may not make much distinction between various anchoring statements [55]. Conflicting findings exist with respect to whether single ratings tend to capture distress to a greater degree than sensory intensity [56], or vice versa [57]. It is not clear to what extent differences in language/culture or diagnosis influence how patients or research subjects construe anchor statements [56, 57].

A limitation of a single-item rating is that it represents only one dimension at a time. With VASs or NRSs, anchors commonly refer to the intensity of sensation or severity of unpleasantness, distress or bother [58–61]. It is not unusual for multiple single-item ratings to be used together to capture different time points or intervals (e.g. right now, worst in past 24 h and on average over last 24 h) [60–62] or multiple symptoms [63]. If practitioners or researchers are using multiple unidimensional ratings to capture more than one measurement domain, it is important to instruct patients or subjects clearly and consistently about each rating and how to distinguish between them [33, 64]. In addition, the practicality of using multiple single-item scales in the palliative care setting requires careful consideration. For example, BOOTH et al. [15, p. 27] recommend assessing clinical breathlessness in a palliative care setting with three 0–10 NRSs: for severity of breathlessness (0=not breathless, 10=worst breathlessness you can imagine), severity of anxiety (0=not anxious at all, 10=worst anxiety you can imagine) and confidence in one’s ability to self-manage breathlessness (0=not confident at all, 10=extremely confident). They also recommend asking whether activity has increased, decreased or remained about the same since the initial or most recent evaluation [15].

In addition, equivalence across single-item ratings with different levels of measurement cannot be assumed, despite what may seem like semantic similarity. For example, in a recent study with neurologically and cognitively intact adult patients with cardiopulmonary disease or lung cancer, participants were asked the binary question “Are you short of breath? (Yes/No)” and were also asked to categorise current breathing distress as none, mild, moderate or severe [52]. Approximately 53% (72 out of 136) answered no to the binary shortness-of-breath question, whereas only half as many (36 out of 136) used none as the ordinal breathing distress rating. Over half of those who answered no to the binary question about shortness of breath (38 out of 72) applied an ordinal rating of at least mild to breathing distress [52]. However, a recent analysis among patients with refractory breathlessness due to life-limiting illness found an equivalence between a 0–10 NRS and a four-level categorical rating (0=none, 1–4=mild, 5–8=moderate, 9–10=severe) based on concurrent administrations [65].

Unable to self-report

The Respiratory Distress Observation Scale (RDOS) is an observational rating designed for use with patients unable to self-report [50, 51, 66, 67]. Eight signs associated with respiratory distress are each scored from 0 to 2: fearful facial expression, restlessness, accessory muscle use, paradoxical breathing, nasal flaring, end-expiratory grunting, heart rate and respiratory rate. Total scores can range from 0 to 16, with higher scores indicating greater respiratory distress [51].

A common approach to validation involves concurrent administration of other measures of the same (or a similar) construct. To the extent that this involves concurrent self-reports of breathlessness by patients capable of providing them [50, 51, 68], validation to date has involved populations other than those for whom clinical use is intended. This, in turn, can create a ceiling effect attenuating the correlation of RDOS scores with self-reports of breathlessness [52], which have been on the order of r≈0.4, regardless of scale type (NRS or VAS) or population (advanced lung disease with hypoxaemia [50], palliative care consultation [51], cancer inpatients [69] or intensive care patients [68]), or whether the concurrent rating ostensibly pertained to breathing difficulty [50], breathing distress [51], shortness of breath [69] or breathing discomfort [68]. These findings would seem to support a hypothesis that, regardless of anchors, patients tend to construe a single breathlessness rating as a self-report of affective distress [56] and that the RDOS should, in keeping with its name, be referred to as a rating of respiratory distress rather than breathlessness per se (table 2). CAMPBELL AND TEMPLIN [52] recommended that an RDOS of ≤2 in a patient whose initial score was ≥3 might be considered consistent with achieving reasonable relief from respiratory distress. However, this conclusion was based on a study with adult inpatients with lung cancer, heart failure, pneumonia or COPD. Therefore, further validation is needed, ideally with palliative care patients unable to self-report.

Table 2. Unidimensional measures of sensory-perceptual and affective distress measurement domains

Scale [refs] | Construct(s) and time frame(s) | Responsiveness | Ease of use | Clinically important difference | Limitations |

NRS or VAS [40–42] | Intensity or distress at present (“now”) or recall of recent past event (e.g. decision to seek emergency care), or interval (e.g. past 24 h) | Generally high in a variety of clinical and experimental contexts | Simple to use | 1 point (0–10 NRS) [45]; 9–12 mm (100 mm VAS) [46, 47] or relative score change of ∼10% of scale range [48] | Reliability indeterminate for single-item ratings |

Modified Borg category-ratio scale [43, 44] | Perceived exertion/effort at present (“now”) or immediate past time point (e.g. end or peak of exercise test) or interval (e.g. past 24 h) | Generally high in a variety of clinical and experimental contexts | Scaling may require some explanation (e.g. meaning of a 0.5 rating or ratings without verbal categories) | 1 point [45, 46] | Potential response bias against numerical levels with no corresponding verbal category [49] |

RDOS [50, 51] | Respiratory distress at a specific point in time or serial time points | Responsive to treatment with opioids [51] | Need to train observers and ascertain inter-rater agreement | RDOS ≤2 consistent with minimal to no distress; ≥3 moderate to severe distress [52] | To date, concurrent validation against self-reported breathlessness ratings [52, 51] |

RDOS: Respiratory Distress Observation Scale. | |||||

A study of ICU patients found that a modification of signs and scoring correlated more strongly with a concurrent breathlessness VAS in a validation cohort (r=0.54, 95% CI 0.39–0.70; n=100) than the original RDOS had in a derivation cohort (r=0.43, 95% CI 0.29–0.58; n=120) [68]. The scoring modification was based on heart rate, inspiratory use of neck muscles, inspiratory abdominal paradox, fear expression and supplemental oxygen use (i.e. it did not include respiratory rate, restlessness, grunting or nasal flaring, which may be affected by sedation or intubation and thus are less appropriate for assessment in this setting) [68].

Multidimensional measures

The experience of breathlessness is multidimensional [2, 11, 13, 28, 31, 70–72], but, with respect to sensory-perceptual and affective measurement domains (as opposed to, for example, impacts on QoL or functional ability), relatively few breathlessness measures have been developed with this explicitly in mind. In PEOLC, it is often the case that treatment may not alter the underlying pathophysiology or breathing mechanics. Therefore, in clinical practice and research in such settings, it is potentially important to distinguish between the intensity of breathlessness sensation(s) and the intensity of the emotional response to breathlessness, because the latter may be more responsive to treatment. Multidimensional measures that incorporate sensory-perceptual and affective domains of breathlessness include the Cancer Dyspnoea Scale (CDS) [73, 74], the Dyspnoea-12 (D-12) [37, 75] and the MDP [33] (table 3).

Table 3. Multidimensional measures of sensory-perceptual and affective distress measurement domains

Scale [refs] | Construct(s) and time frame(s) | Responsiveness | Ease of use | Clinically important difference | Limitations |

Cancer Dyspnoea Scale [74, 76] | Severity of sense of effort, anxiety and discomfort related to breathing difficulty, over the past few days | Responsive to nebulised furosemide [77] | ≤2.5 min to complete [76, 78] | Not determined | Validated for advanced cancer only |

Dyspnoea-12 [37, 79, 80] | Overall dyspnoea severity or severity of physical (sensory-perceptual) affective aspects of breathlessness, which occurs “these days” | Score change over 2 weeks parallels transition scores for general health in adults with asthma [79] | Rated by patients with COPD, ILD and heart failure as easily understood and easy to use [37] | 3 points recommended for sample size estimation purposes [81] | Needs further validation in palliative care |

MDP [33, 34, 82] | Unpleasantness/discomfort in breathing, severity of sensory qualities (immediate perception) and affective distress (emotional response), “now” or referred to a particular event or time point | Responsive to nonspecific ED treatment [34, 82] and to inspiratory muscle training in pulmonary rehabilitation [83] | Requires some training to administer; takes <5 min on initial administration and ∼2 min subsequently [33, 34, 84] | Not determined for immediate perception or emotional response domains; unpleasantness rating likely to be similar to other NRSs (see table 2) | Needs validation in patients with advanced cancer and in palliative care |

The CDS comprises 12 items related to “breathlessness or difficulty in breathing … during the past few days” among patients with advanced cancer [76]. It has three subscales: sense of effort (five items; scale range 0–20; e.g. “Do you feel as if you are panting?”), anxiety (four items; scale range 0–16; e.g. “Do you feel as if you are drowning?”) and discomfort (three reverse-scored items; scale range 0–12; e.g. “Can you inhale easily?”). A higher score indicates a worse status. In patients with lung cancer, the subscales have adequate internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s alpha=0.8–0.9), with moderate correlations across factors [76, 85]. For the total score (range 0–48), a cut-point of ≥8 versus ≤7 points had approximately 62% sensitivity and 78% specificity for dyspnoea interference with any daily activity [74]. The CDS was originally created in Japanese [73, 74, 76]. Translations have been validated in Swedish [78, 86, 87] and English [85]; however, minor inconsistencies of factor structure have been found across different languages (e.g. one item in the English translation and a different item in the Swedish translation loaded primarily to a different factor from the original CDS [76, 78, 85], and, in the English translation, several items had more ambiguous loadings across factors [85]). The developers of the English version proposed a “reduced” scale with just three items per subscale to minimise these discrepancies and simplify scoring [85].

The D-12 [37, 79, 80, 88] was developed using Rasch modelling [36]. Rasch analysis (a one-parameter variant of item-response analysis) locates items and respondents along the same continuum of “item difficulty” (which, in a symptom measure, can be construed as symptom severity). The 12 items represent sensory-perceptual (e.g. “I have difficulty catching my breath”) and affective distress (e.g. “My breathing makes me feel miserable”) domains of breathlessness. Each item is scored using a four-point numerical scale (0=none, 1=mild, 2=moderate, 3=severe); total scores range from 0 to 36. The instrument can also be scored for physical and emotional components comprising seven and five items, respectively, for component scores ranging from 0 to 21 for the physical component items and from 0 to 15 for the emotional component items. The time frame for items is “these days”, rather than a specific interval or activity; the less-specific time frame may be useful in a palliative care context. Based on data from a randomised, controlled feasibility trial of a non-pharmacological intervention for self-managing the breathlessness–cough–fatigue symptom cluster in patients with lung cancer, an MCID of 3 points in the total D-12 score has been recommended [81].

The D-12 has been validated in patients with COPD [37, 89, 90], ILD [37, 75, 80], heart failure [37], asthma [79] and pulmonary arterial hypertension [88]. In addition to English, psychometric data on an Arabic version have been published [90]. Translations into a number of other languages are available (J. Yorke, unpublished data).

The MDP is based on a conceptual model of sensory-perceptual and affective processing with origins in pain research [28, 33]. It was developed to be used in either laboratory experiments [33, 91] or in clinical studies of patients with a variety of cardiopulmonary diseases in acute care settings [34, 82]. Recently, extensive validation was published pertaining to use with community-residing persons with COPD [84]. As yet, no studies have been published on its use in palliative care, although it has been used with patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis comparing spontaneous breathing with NIV [92]. The MDP has one item pertaining to overall unpleasantness or discomfort of breathing (“how bad your breathing feels/felt”), five sensory quality (SQ) items (based on factor analytic studies of dyspnoea descriptors [35, 93]; e.g. “I am not getting enough air, I am smothering or I feel hunger for air”) and five emotion items (e.g. frustrated). The unpleasantness and emotional response items are rated using 0–10 NRSs with appropriate anchors (0=neutral, 10=unbearable for unpleasantness; 0=none, 10=the most I can imagine for negative emotions). The SQ items are rated first for whether a given grouping does or does not apply and which most accurately describes the individual’s breathlessness. The intensity of each SQ grouping is then rated on a 0–10 NRS (0=none, 10=as intense as I can imagine). The time frame for ratings can be “right now”, a specific time point (e.g. last minute of an experimental stimulus) or event (e.g. when someone decided to seek emergency care), or is potentially customisable to a particular context of use (e.g. worst episode in the past 2 weeks [84]).

The MDP has been used in patients with a variety of cardiopulmonary conditions, in particular COPD, heart failure and pneumonia [34, 82, 84], as well as in healthy subjects exposed to experimental stimuli [91]. It is published in English and French versions [33], and translations into other languages are being developed.

Complete versions of the D-12 [88] and MDP [33] have been published, and extensive psychometric data are available in the publications cited for each. A comparison of the items in both instruments is also available [33]. Neither is diagnosis specific, which is a potential advantage for palliative care, but so far only the D-12 has been validated in lung cancer [81], and further research is needed to support their use in a palliative care setting.

Measuring breathlessness impact or burden

Measures of the impact of breathlessness are commonly focused on functional impact (e.g. activity limitation or disability) or impact on QoL. Symptom burden does not have a consistent theoretical definition but is typically assessed with inventories of multiple symptoms [21, 23].

Functional impact

Unidimensional

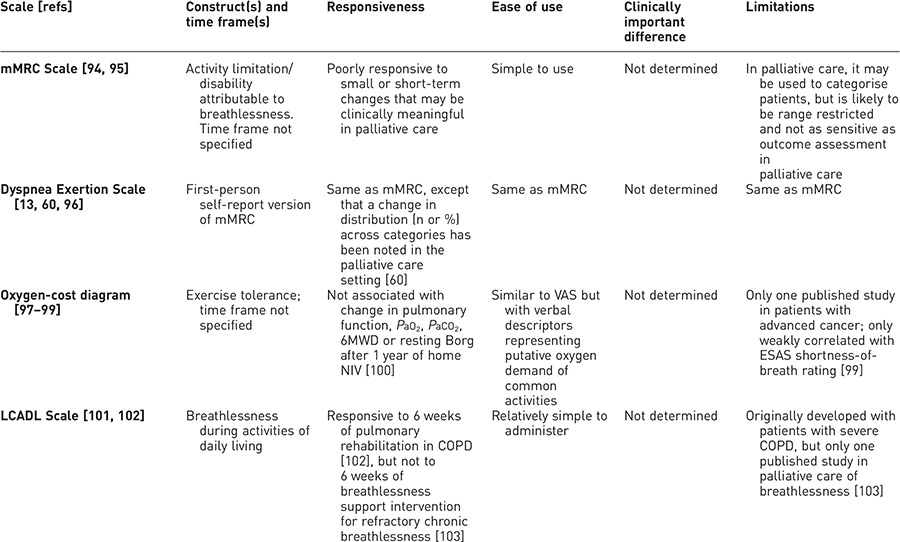

In palliative care, most unidimensional functional impact measures related to breathlessness have only limited validation or have issues related to responsiveness (table 4). The three shortness-of-breath items (at rest, walking and climbing stairs) from the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Quality of Life Questionnaire Lung Cancer 13 module (QLQ-LC13) [27, 106] have been used as a functional impact scale [104]. The developers recommend that all three shortness-of-breath items must have valid responses to be treated as a scale; if any have missing values, the others can be used separately, as single items [104].

Table 4. Unidimensional measures of functional impact

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree