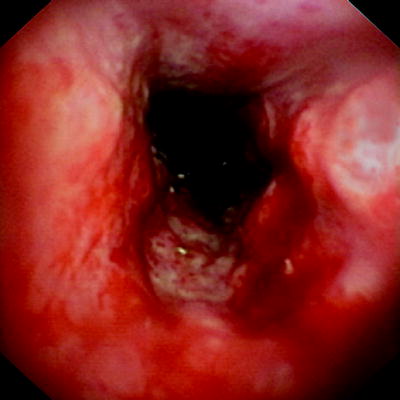

Fig. 40.1

Injured subglottic airway displays mucosal ulceration and incomplete reepithelialization (arrows) with hemorrhagic areas and collagen deposition. This altered healing process may lead to airway stenosis

Etiology and Pathogenesis

During the first decades of the twentieth century, infection and external airway trauma were the primary causes for SGS. In the late 1960s, the incidence of acquired SGS began to increase as a result of long-term intubation and other invasive procedures of the airway. Currently, common etiologies resulting in SGS are endotracheal intubation, tracheotomy, previous airway surgery, neoplasms, and radiation for oropharyngolaryngeal tumors. Other causes, while rare, are important to consider when evaluating SGS of unclear etiology (Table 40.1).

Table 40.1

Causes for subglottic stenosis

Congenital | Membranous |

Increased fibrous connective tissue, hyperplastic submucous glands, granulation tissue | |

Cartilaginous | |

Cartilage deformity (small or elliptical cricoid, large anterior or posterior lamina, generalized thickening, submucous cleft), trapped first tracheal ring | |

Combined stenosis | |

Acquired | Trauma |

Post-intubation, previous airway surgery (high tracheotomy, percutaneous tracheotomy, cricothyroidotomy, prior surgery), accidental (foreign body, thermal, or caustic inhalation, radiation, blunt, or penetrating trauma) | |

Infection | |

Tuberculosis, syphilis, leprosy, diphtheria, bacterial tracheitis, croup, typhoid fever, scarlet fever, laryngeal scleroma | |

Inflammatory and autoimmune diseases | |

Wegener’s granulomatosis, relapsing polychondritis, amyloidosis, sarcoidosis, systemic lupus erythematosis, inflammatory bowel disease, gastroesophageal reflux | |

Tumor | |

Carcinoma, hemangioma, papilloma | |

Other | Idiopathic subglottic stenosis |

SGS can be classified as congenital and acquired. The acquired form is much more frequent than the congenital type and can be subdivided into traumatic, inflammatory, infectious, and tumoral. An additional inadequately characterized female population suffers from idiopathic SGS (ISGS).

Congenital SGS

Even though this type of stenosis is uncommon, it is the third most frequent congenital airway problem. A malformation of the cricoid cartilage is linked to inadequate recanalization of the laryngeal lumen upon conclusion of the normal epithelial fusion at the end of the third month of gestation. Different degrees of atresia, stenosis, or webbing can be found in these patients (Fig. 40.2). Histopathologically, congenital SGS can be subdivided into cartilaginous and membranous. The cartilaginous type results from a thickened or distorted cricoid cartilage, creating an anterior subglottic shelf that extends to the posterior region. It is frequently more severe than the membranous stenosis and is rarely managed successfully with endoscopic techniques. The membranous form is more common, circumferential, often involving the true vocal cords, and is characterized by fibrous soft tissue thickening.

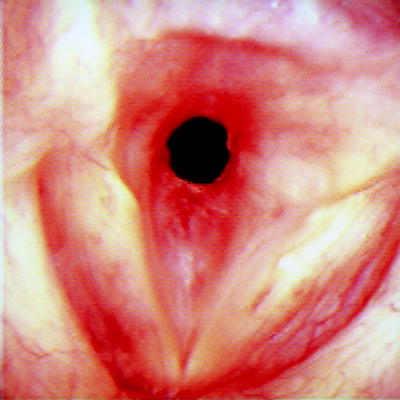

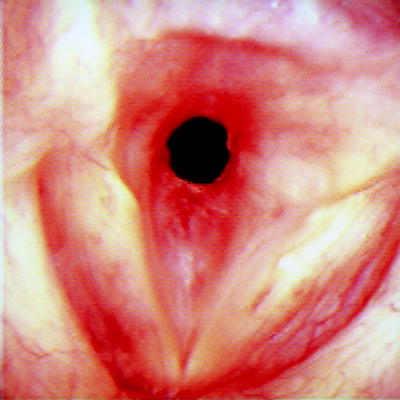

Fig. 40.2

Congenital subglottic web with Myer-Cotton grade I cricoid cartilage stenosis. This thin web was mechanically broken

Laryngeal Trauma

Trauma is the most frequent cause of acquired laryngeal stenosis in children and adults. Internal subglottic trauma is usually iatrogenic (e.g., endotracheal intubation, tracheotomy, or prior tracheal instrumentation). External trauma can be originated by contusion, penetrating wound, or inhalation injury.

In SGS caused by intubation, several risk factors have been identified such as prolonged intubation, large-caliber endotracheal tube, traumatic intubation, numerous re-intubations, local infection while intubated, frequent displacement of the endotracheal tube, and the concomitant existence of a nasogastric tube (Fig. 40.3a). The pathogenesis of this form of acquired SGS is not fully understood. The more widely accepted theory proposes that high pressure from a tube or cuff exceeds the capillary pressure of the airway wall and contributes to ischemia of the mucosa and cartilage (Fig. 40.3b). The three overlapping phases of wound repair are inflammation (initial injury generates edema and vascular congestion with recruitment of cells and mediators, occasionally ulceration and infection can occur), proliferation (reepithelialization, neovascularization, increased fibroblast activity, granulation tissue), and airway remodeling (collagen deposition, scar formation, contracture, and loss of structural integrity leading to stenosis).

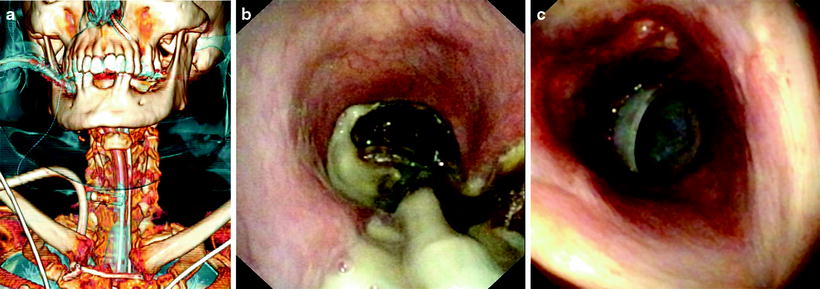

Fig. 40.3

CT reconstruction of a 78-year-old female with subglottic stenosis caused by prolonged endotracheal intubation (a). Multiple comorbidities, high position of the tube, excessive cuff pressure, and the presence of a nasogastric tube contributed to an extensive mucosal and cartilage damage (b). A straight silicone stent 12/40 mm was deployed (c)

Postsurgical SGS may occur as a complication of previous tracheotomy, percutaneous tracheotomy, cricothyroidotomy, and surgical treatment for airway neoplasms. Stenosis following tracheotomy may be above the stoma, at the same level as the stoma, at the cuff site, and at the tip of the cannula. In addition to ischemic mucosal injury and chondritis, fracture of the cartilage is an important factor for SGS in these patients. Damage to the cartilage above the stoma is the most frequent cause of stenosis after emergency tracheotomy performed with a poor technique.

The incidence of traumatic SGS can be radically reduced if high tracheotomy and cricothyroidotomy are only performed in extreme emergencies; aggressive endoscopic manipulation for benign laryngeal lesions is avoided; intubation and endoscopy are done gently on calm patients; factors contributing to laryngeal trauma secondary to intubation are recognized and prevented when possible.

Infection

Acute laryngotracheobronchitis, an acute viral respiratory disease commonly seen in children, can cause subglottic narrowing. Croup most commonly occurs in children 6–36 months of age, and it is rare beyond the age of 6. Acute bacterial tracheitis can also originate thick, purulent secretions and mucosal edema that may cause symptoms of upper airway obstruction.

SGS secondary to chronic infection is rare, except in certain endemic geographic areas, and it has been described in patients with tuberculosis, syphilis, diphtheria, typhoid fever, scarlet fever, leprosy, and laryngeal scleroma.

Though infrequent, subglottic and endotracheal tuberculosis may result in significant obstruction related to the initial lesion or subsequent stricture formation. Some degree of stenosis may still develop despite appropriate antituberculosis chemotherapy.

Laryngeal scleroma is also an uncommon chronic disease originated by an aerobic gram-negative bacteria, Klebsiella rhinoscleromatis. It is prevalent in certain regions such as Africa, Asia, Central and South America, and Central and Eastern Europe. It typically involves the nose but can also affect other parts of the respiratory system. Subglottic involvement is reported in 23% of cases. Following the initial infection, three sequential phases are described: exudative stage, with active inflammation, edema, congestion, and necrosis; proliferative stage characterized by multiple reddish nodules; and fibrotic stage with cicatricial tissue. Clinical suspicion is important in order to achieve the diagnosis. The CT scan normally shows concentric irregularities and narrowing in the subglottic space. Biopsy specimens are needed for the definitive diagnosis, usually obtained during the proliferative phase. There is a recognizable histological pattern with clusters of vacuolated histiocytes – Mikulicz cells. Treatment should be directed according to clinical stage, severity, and anatomic location. In the proliferative phase, long-term antibiotics are the treatment of choice. In the fibrotic stage, if the patient is symptomatic and there is mild subglottic involvement, endoscopic procedures can be valid therapeutic options. Open surgical techniques have been attempted for extensive SGS.

Wegener’s Granulomatosis

Wegener’s granulomatosis (WG) is a multisystemic disease characterized by necrotizing vasculitis and granuloma formation that has a predilection for the upper and lower respiratory tracts and kidneys. Its etiology is unknown and affects both males and females with a peak around 40–55 years old. The course of WG varies widely, from localized to multisystemic, from mild to life-threatening disease. Nasal and sinus findings are present in a high percentage of cases (e.g., chronic sinusitis, epistaxis, septal perforation, saddle nose deformity). SGS may occur either as a presenting characteristic or as a late-stage manifestation of the disease and is reported in 12–23% of WG patients (Fig. 40.4). It often occurs independently from other features of disease activity and frequently does not improve with systemic treatment. Laboratory studies may show a positive anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies (ANCA-c) test, although it should be interpreted cautiously because ANCA-c may be positive in other diseases and WG may be present in face of a negative ANCA test. Chest radiographs and CT scans may show pulmonary infiltrates and/or cavitary nodules. Biopsy remains the gold standard for the diagnosis, but specimens from the larynx and trachea often do not exhibit the characteristic inflammatory infiltrates with multinucleated giant cells, granuloma formation, and vasculitis of the small and medium vessels. Systemic immunosuppressive therapy is the mainstream treatment in WG. The endoscopic management of subglottic lesions (laser resection, serial dilatations, topical corticosteroids, local mitomycin-c) is an important aspect in those who remain symptomatic despite appropriate medical management.

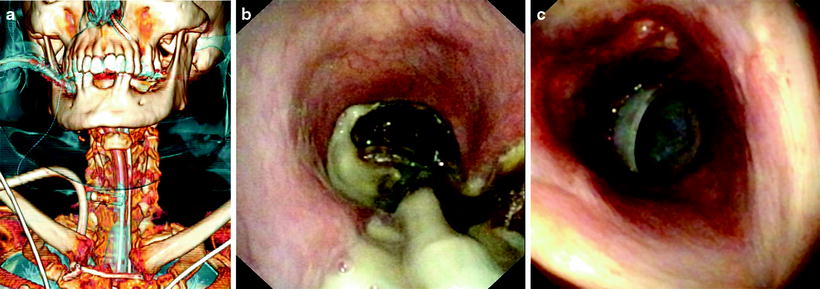

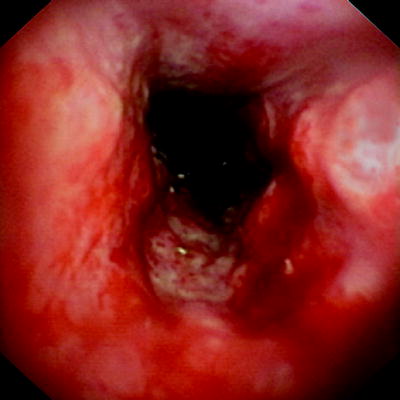

Fig. 40.4

Subglottic stenosis in Wegener’s granulomatosis. One can notice the red inflammatory friable tissue circumferentially narrowing the subglottis

Amyloidosis

Amyloidosis is a disorder characterized by extracellular tissue deposition of fibrillar proteins and can involve virtually any organ or system. It can be idiopathic or associated to inflammatory, hereditary, or neoplastic diseases. Respiratory tract amyloidosis may be part of a widespread or local process. Sites in the larynx that show predilection for nodular or polypoid amyloidosis include the ventricles, false cords, aryepiglottic folds, and the subglottis. Pulmonary manifestations comprise tracheobronchial infiltration, persistent pleural effusions, and parenchymal nodules. There may be diffuse narrowing and wall thickening, circumferential airway involvement, often with ossification of the amyloid deposits (Fig. 40.5). Bronchoscopy displays multiple plaques or localized tumor-like masses. Tissue biopsy stained with Congo red and examined under polarized light shows the characteristic submucosal extracellular deposits of amyloid protein that confirms the diagnosis. Bronchoscopy-based techniques (laser therapy, stenting) have been suggested as a possible method for dealing with subglottic obstructing lesions. There is no effective medical treatment and excision, when possible, remains the treatment of choice in localized forms of amyloidosis.

Fig. 40.5

Bronchoscopic appearance of laryngotracheal amyloidosis in a 37-year-old female patient. Amyloid deposits infiltrate the mucosa reducing airway caliber

Relapsing Polychondritis

Relapsing polychondritis (RP) is a multisystemic immunemediated disease characterized by recurrent episodes of inflammation of cartilaginous structures. RP is most likely between age 40 and 60, although it can occur in younger patients. One-third of cases develop in association with another recognizable condition, particularly systemic vasculitis or connective tissue diseases. Auricular chondritis represents the usual initial presentation, but the disease may involve the nose, laryngotracheobronchial tree (malacia and/or stenosis), peripheral joints, and other organs. In the active stage, there is a red, warm, painful swelling of the cartilage. After the inflammatory episode, significant destruction may occur. The definitive diagnosis is based on the presence of three of the following criteria or at least one along with a confirmatory biopsy showing inflammatory changes in the cartilage: recurrent bilateral auricular chondritis, nonerosive inflammatory polyarthritis, nasal cartilage chondritis, ocular inflammation, respiratory tract chondritis, and cochlear or vestibular damage. CT and bronchoscopic findings include diffuse smooth thickening of the larynx, trachea, and proximal bronchi; thickened, densely calcified cartilaginous rings with spared posterior tracheal membrane; tracheal wall nodularity; diffuse narrowing of the tracheobronchial lumen, major airway collapse caused by destruction of cartilaginous rings (Fig. 40.6). It is difficult to predict the clinical path of the disease because it can have an indolent course or fulminating consequences. This means that it is important to perform a prompt diagnosis and treatment plan before irreversible damage occurs. Medical management of RP focuses on suppressing the acute inflammatory process. Ernst and coworkers have shown that it is feasible to treat these patients by endoscopic procedures (dilatation, stenting). The majority experience improvement of respiratory symptoms although on occasion, involvement of glottis and subglottic regions may necessitate a tracheotomy.

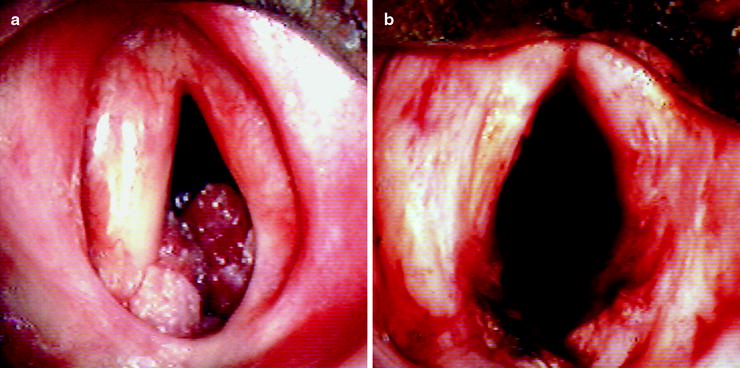

Fig. 40.6

Firm thickening of the subglottis in a patient with relapsing polychondritis (Courtesy of Armin Ernst, M.D.)

Tumor

Direct extension of a locally advanced tumor and/or extrinsic compression may cause SGS (e.g., laryngeal cancer, thyroid tumors). Primary laryngeal and tracheal tumors are extremely rare in children, with papillomas, hemangiomas, and granular cell tumors being the most common. In adults, squamous cell carcinomas followed by adenoid cystic carcinomas are the most frequent and in some instances may cause SGS. Other less common tumors in adult patients include hemangiomas, neurogenic tumors, and papillomas.

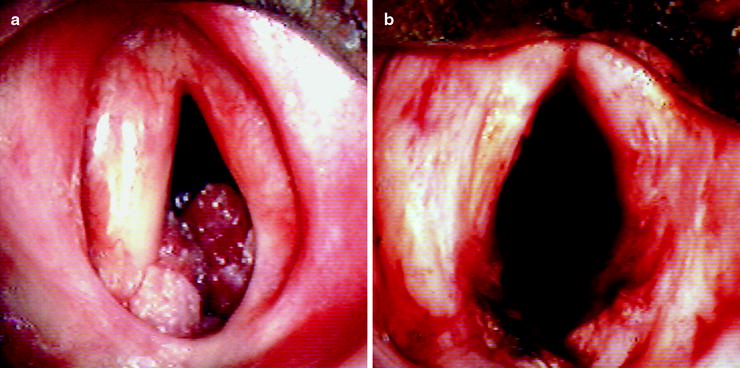

Recurrent papillomatosis results from infection of the upper respiratory tract by the human papilloma virus (HPV). HPV6 and 11 are most commonly involved, while HPV16 has been reported and may be associated with an increased risk of malignant degeneration. This disease is most common in children but may also occur in adults, as previously stated. Infection frequently occurs during birth, and laryngeal papillomas may lead to contamination of the trachea and lungs. At bronchoscopy, the papillomas have a polypoid appearance and may involve the larynx, trachea, or bronchi (Fig. 40.7). Endoscopic interventions are crucial since repeated treatment is usually required because recurrence is quite common.

Fig. 40.7

Glottic and subglottic cauliflower-like tumors with smooth surface corresponding to recurrent papillomatosis in a 42-year-old (a). There was a marked improvement in airway caliber after laser treatment (b)

Idiopathic Subglottic Stenosis

ISGS is a rare inflammatory process of unknown cause, usually limited to the subglottic region and the first two tracheal rings. It is an exclusion diagnosis based on the absence of recent intubation or trauma, and other rare diseases that can affect the subglottis. Some reports advance a hormonal cause, since most patients are females with preponderance in the 20–50 age range, although no major causal factor was identified. Mark et al., in 63 tracheal resections performed in patients with the diagnosis of ISGS, found an extensive fibrosis, dilation of mucus glands, a relatively normal cartilage, and in most cases, a positive staining for estrogen and progesterone receptors in fibroblast cells. The theory of laryngopharyngeal reflux as a possible etiological factor seems to be excluded by recent reports given the poor responses to anti-gastroesophageal reflux medication. A new hypothesis suggests that severe coughing episodes may cause mechanical trauma, intermittent disruption of blood supply to the cricoid, and scarring in the subglottic area leading to ISGS. Dilatation, laser incisions, intralesional steroids, mitomycin-c, and airway stenting have all been used for the initial management of ISGS.

Other Causes

Gastroesophageal reflux has been proposed as a medical condition that may exacerbate the pathogenesis of SGS, be the single cause for stenosis, or cause restenosis after repair. Roh and colleagues have induced subglottic injury in a rabbit model demonstrating that the inflammation scores, fibrosis, thickening, and luminal stenosis were greatest in the acid reflux group compared to the nonacid reflux group, suggesting that subglottic wound healing is significantly affected by acidic conditions. Active empirical treatment is recommended for this condition in patients undergoing SGS treatment.

Additional systemic factors may also increase the risk of subglottic injury and decrease the rate of wound healing (e.g., diabetes mellitus, immunodeficiency, and chronic infections).

Diagnosis and Pre-interventional Assessment

SGS is generally suspected based on the clinical findings. Congenital SGS usually occurs in very early life with symptoms of airway distress and laryngeal involvement: feeding abnormalities, stridor, abnormal or absent cry, and hoarseness. If the stenosis is severe, the neonate will present major respiratory distress at birth. Congenital SGS is often associated with other malformations, and the presence of further causes for respiratory compromise should always be assessed. Adults with mild congenital stenosis are usually asymptomatic and are diagnosed after a difficult intubation or while submitted to bronchoscopy for other reasons (Fig. 40.2).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree