Infection

Tuberculosis/mycobacterial infection

Bronchiectasis

Fungal infections (primary or mycetoma)

Lung abscess

Paragonimiasis

Hydatid cyst

Necrotizing pneumonia

Septic emboli

Neoplasm

Lung cancer (non-small or small cell)

Pulmonary carcinoid

Endobronchial metastases

Parenchymal metastases

Autoimmune

Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage

ANCA-associated granulomatous vasculitis (formerly Wegener’s granulomatosis)

Goodpasture syndrome

Microscopic polyangiitis

Polyarteritis nodosa

Systemic lupus erythematosus

Rheumatoid arthritis

Systemic sclerosis

Cardiac/vascular

Arteriovenous malformation

Mitral stenosis

Pulmonary embolism/infarct

Congenital heart defects

Pulmonary hypertension

Aortic aneurysm

Bronchoarterial fistula

Congestive heart failure (systolic and/or diastolic)

Pulmonary vein stenosis following atrial fibrillation ablation

Iatrogenic

Bronchoscopy

Transthoracic needle aspiration

Transbronchial biopsy

Pulmonary artery catheterization

Tracheo-innominate artery fistula

Radiotherapy

Targeted chemotherapeutic agents (e.g., bevacizumab)

Trauma

Blunt chest trauma

Penetrating chest trauma

Other

Pseudohemoptysis

Bone marrow transplantation

Cardiovascular Disease

There are a variety of cardiac and vascular hemoptysis sources (see Table 44.1). Among the primary cardiac hemoptysis sources, elevated pulmonary venous pressure leads to venous dilation and varix formation which may rupture and bleed during sudden pulmonary venous pressure increases (e.g., systolic or diastolic failure, cough, Valsalva). Hemoptysis is generally self-limited but can be rarely severe. In a similar fashion, localized pulmonary venous hypertension from pulmonary vein stenosis following atrial fibrillation radiofrequency ablation can result in massive hemoptysis. Similar to their tendency to bleed in other anatomic locations, pulmonary arteriovenous malformations can bleed spontaneously and cause massive hemoptysis.

Iatrogenic Causes

A number of invasive procedures may be complicated by massive hemoptysis. Massive hemoptysis during bronchoscopy is rare and usually occurs in the setting of platelet dysfunction, thrombocytopenia, or coagulopathy when transbronchial biopsies are performed. Pulmonary artery catheter flotation may cause pulmonary artery rupture and has been reported to have a mortality rate greater than 50%. Avoiding balloon overinflation and insuring balloon deflation prior to catheter advancement can help avoid this potentially lethal complication.

A tracheal-innominate artery fistula (TIF) may develop in the chronic tracheostomy setting. A low tracheal insertion (below the recommended first to third tracheal rings) or a high innominate artery may predispose to TIF formation. One potential clue of TIF is the “sentinel bleed” – a small amount of fresh tracheal blood that appears usually 2 weeks or more after tracheostomy placement that can be a harbinger of a catastrophic, fatal bleed.

Massive hemoptysis is a known thoracic radiotherapy complication which more commonly occurs with endobronchial brachytherapy than external beam radiotherapy. Bleeding usually occurs from bronchovascular necrosis and erosion.

Trauma

Massive hemoptysis may occur in the chest trauma setting. Blunt trauma can cause airway rupture with associated injury to the pulmonary or bronchial vasculature. Alternatively, fractured ribs can cause a lung laceration with hemoptysis and/or hemothorax. Similarly, penetrating trauma can directly lacerate the pulmonary, bronchial, or other major vascular structures, causing hemoptysis and/or hemothorax.

Other

An important massive hemoptysis source to always consider is “pseudohemoptysis” or bleeding from a source other than the lung. Epistaxis and hematemesis are two common scenarios that can mimic hemoptysis and patients may be unable to differentiate the bleeding source. Therefore, if pseudohemoptysis is suspected, involving an otolaryngology or gastrointestinal specialist in the patient’s care can be crucial. Bone marrow transplant recipients can develop massive hemoptysis that is not necessarily temporally related to the transplant and is likely due to a microvascular chemotherapeutic injury.

Diagnostic Approach

History and Physical Exam

Though rarely able to diagnose the massive hemoptysis etiology in isolation, the basic history and physical exam can provide initial clues as to underlying etiology, but taking a history should not delay urgent interventions. Physicians should elicit any recent history of infectious symptoms. Particular attention should focus on eliciting any prior underlying lung or cardiac disease, any prior occupational or tobacco exposures, any connective tissue disease associated symptoms, or any family lung or bleeding disorder history.

If the patient is stable enough for examination, the physician should note the presence of any pulmonary exam findings that might indicate laterality of the massive hemoptysis source. Evidence of congestive heart failure or a malignancy can guide diagnostic evaluation implementation and provide an impression of how quickly the patient requires definitive management.

Laboratory Studies

Initial tests should include a complete blood count, coagulation studies, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and urinalysis. These study results may provide clues to the presence of any underlying systemic disorders (e.g., coagulopathy, autoimmune pulmonary-renal syndromes). Serologies can be sent to evaluate for a suspected pulmonary-renal syndrome. Sputum and blood cultures should be performed to look for pathogenic organisms when an infectious source is suspected.

Radiographic Studies

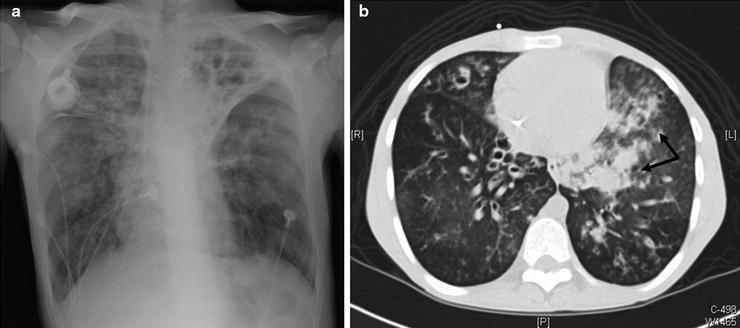

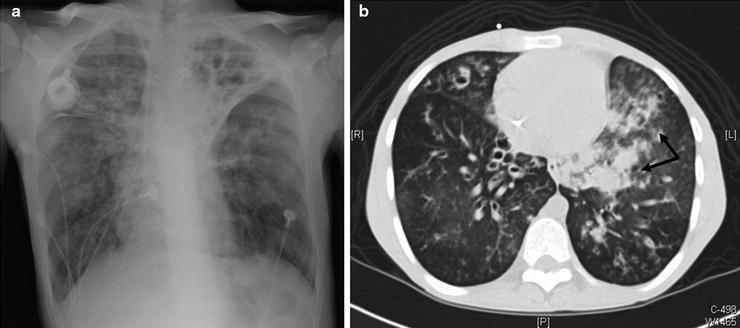

Radiographic studies form the diagnostic evaluation backbone in massive hemoptysis. A guiding principle is to localize a lesion upon which intervention may be performed if necessary. The standard chest radiograph (CXR) is (Fig. 44.1a) an important initial tool that can identify pathologies like cavitary lesions, tumors, lobar or alveolar infiltrates, infarcts, and/or mediastinal masses. However, the standard CXR false-negative rate can be up to 20–40%.

Fig. 44.1

A 25-year-old cystic fibrosis patient presented to the emergency department after 650 ml of bright red blood hemoptysis over a 10-min period. The hemoptysis spontaneously reduced without intervention to blood streaked sputum. A plain film was obtained which demonstrated stable bilateral left greater than right chronic bronchiectatic changes (a). As the patient had stabilized, a CT scan was obtained which demonstrated new left lower lobe ground-glass opacities and infiltrates (arrows) compared to a CT scan from 3 months prior to the current scan. (b) These infiltrates likely represented aspirated blood and localized the bleeding to the left lung which could not be appreciated on the CXR. The patient proceeded to BAE with attention to the left lung vasculature which localized a dilated, tortuous bronchial artery with a small blush which was embolized. In addition, a parasitized internal mammary branch was localized terminating in the vicinity of the bronchial artery and was embolized

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree