23 Management of Heart Failure

Etiology and Pathogenesis

Coronary artery disease (CAD) accounts for 50% of the incidence of HF worldwide. Patients with a previous MI can develop both decreased systolic performance and diastolic impairment due to interstitial fibrosis and scar formation. Hibernating myocardium due to severe CAD can also cause systolic HF, which is potentially reversible with revascularization. Hypertension is a common cause of HF, especially in African Americans and older women. Valvular heart disease accounts for approximately 10% to 12% of cases of HF. A common cause of initially unexplained HF (following exclusion of CAD) is idiopathic cardiomyopathy. Familial cardiomyopathies may account for up to one third of cardiomyopathies thought to be idiopathic. Other etiologies of dilated cardiomyopathy (Chapter 18) include thyroid disease, chemotherapy (anthracyclines, e.g., doxorubicin and trastuzumab [Herceptin]), myocarditis (Chapter 22), infection due to HIV, diabetes, alcohol, cocaine, connective tissue disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, peripartum cardiomyopathy, and arrhythmias. Hypertrophic (Chapter 19) and restrictive (Chapter 20) cardiomyopathies can cause HF, but this is less common.

Systolic Heart Failure

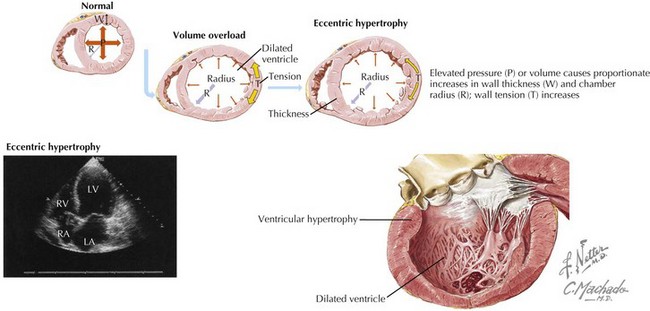

HF generally follows an injury to the myocardium (due to ischemia, a toxic effect, or an increased volume or pressure load on the LV). LV remodeling, a maladaptive response, follows, with resulting changes in cardiac size, shape, and function (Fig. 23-1). Myocyte length increases, with a resulting increase in chamber volume, which preserves stroke volume. Myocyte hypertrophy can also occur, along with a loss of myocytes due to apoptosis or necrosis, and fibroblast proliferation and fibrosis. The heart remodels eccentrically in systolic HF, becoming less elliptical and more spherical and dilated. The mitral valve annulus often becomes dilated, resulting in mitral regurgitation and further increased wall stress.

Figure 23-1 Cardiac remodeling secondary to volume overload.

LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle.

Diastolic Heart Failure

Hypertrophic and restrictive cardiomyopathies can result in a clinical presentation consistent with DHF (see Chapters 19 and 20), as can constrictive pericarditis. Indeed, distinguishing these entities can be difficult, requiring extensive noninvasive and invasive hemodynamic assessment.

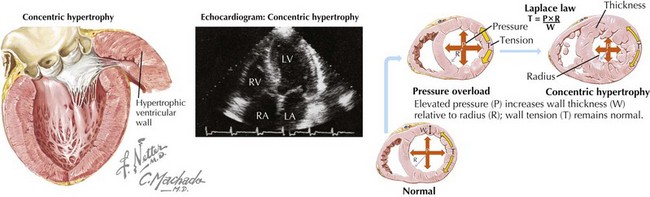

DHF is generally characterized by a normal end-diastolic volume, hypertrophy of the cardiomyocytes, and increased wall thickness resulting in a concentric pattern of LV remodeling as compared with the increased cardiomyocyte length, increased end-diastolic volume, and eccentric remodeling seen in systolic HF (Fig. 23-2). There is increased extracellular matrix, abnormal calcium handling, and activation of the RAAS and sympathetic nervous system. Together, these pathophysiologic changes result in impaired ventricular relaxation, high LV diastolic pressure, high left atrial filling pressures, and resulting symptoms and signs of HF.

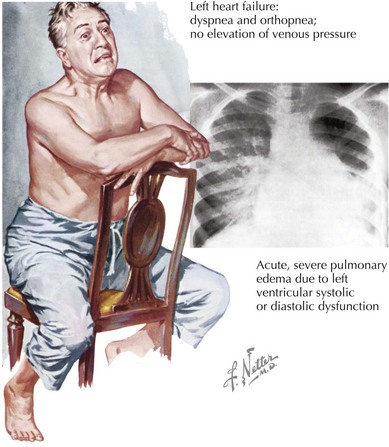

Clinical Presentation

The clinical presentation may be indistinguishable between patients with systolic and diastolic HF (Fig. 23-3). The cardiac silhouette is usually enlarged in both circumstances, with cardiomegaly due to ventricular dilation in systolic HF and from hypertrophy in patients with DHF. An assessment of LV function is essential for determining the appropriate approach to therapy.

Differential Diagnosis

The difficulty in arriving at a new diagnosis of HF lies in its vague symptoms and examination mimickers (Box 23-1). Symptoms of dyspnea and exercise intolerance can be attributed to many diagnoses: lung disease (including chronic obstructive lung disease, reactive airways diseases, thromboembolic pulmonary disease, and pulmonary hypertension), thyroid disease, arrhythmias, anemia, obesity, deconditioning, and cognitive disorders. Signs of volume overload are not specific to HF. Sodium-avid states of nephrosis and cirrhosis, as well as pericardial disease, can present with similar findings of jugular venous distention, hepatomegaly, and edema.

Diagnostic Approach

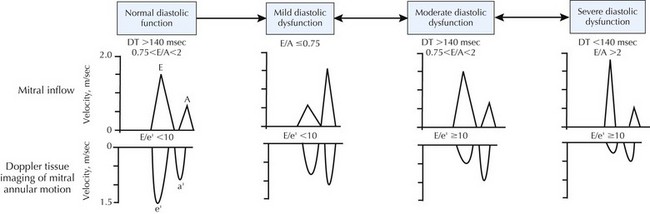

Determining the Type and Degree of Left Ventricle Dysfunction

Echocardiography is the most common method for initial assessment of LV function. EF, valve function, hypertrophy, and diastolic function can all be assessed. Most patients with DHF have impaired LV relaxation, with or without a quantifiable reduction in LV compliance, and preserved EF. The most reproducible and validated method of diagnosing diastolic dysfunction combines echocardiographic two-dimensional M-mode Doppler measurements of mitral valve inflow with the sensitive, relatively load-independent measure of LV relaxation (e′ velocity) obtained by tissue Doppler imaging of the mitral annulus. This approach has resulted in four classifications of diastolic function: normal, mild dysfunction (impaired relaxation, normal filling pressure), moderate dysfunction (impaired relaxation or pseudonormal with moderately elevated filling pressure), and severe dysfunction (restrictive) (Fig. 23-4). Reversibility can be determined with the Valsalva maneuver. An E/e′ ratio that exceeds 15 correlates with elevated filling pressure.

Figure 23-4 Echo-Doppler criteria for assessment of diastolic function.

From Bursi F, Weston SA, Redfield MM, et al: Systolic and diastolic heart failure in the community. JAMA; 2006:296(18):2209—2216. Copyright American Medical Association.