Management of Atrial Fibrillation and Atrial Flutter

Eyal Herzog

Jonathan S. Steinberg

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common cardiac rhythm disturbance encountered in clinical practice, and its prevalence is increasing as the population ages (1,2). Electrocardiographically, AF is characterized by an irregularly irregular ventricular rhythm, with an absence of discrete P-wave activity. Rather, undulating fibrillatory activity (f waves) are seen on the electrocardiogram between QRS complexes and T waves. Sometimes very small “f” waves are difficult to see unless a 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) is done (3). The American College of Cardiology (ACC), the American Heart Association (AHA), and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) established guidelines in 2001 for the management of patients with AF (4).

Atrial flutter (Afl) is less common and is often associated with AF or occurs in an isolated pattern. Guidelines for its management were included in the ACC/AHA/ESC Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Supraventricular Arrhythmias (5). The electrocardiographic findings of Afl include an atrial deflection with rapid regular undulations that gives rise to a sawtooth appearance, mainly in the inferior leads (6). The atrial rate is usually between 250 and 350 beats/minute.

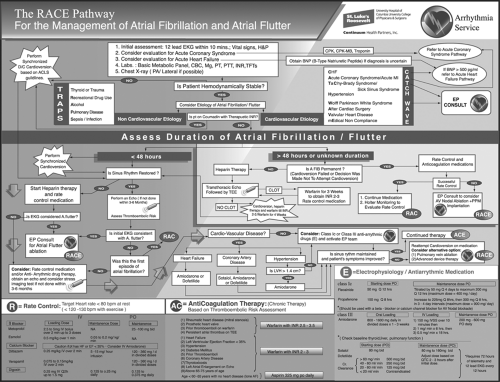

A major limitation of the currently published guidelines for management of patients with AF and Afl is its complexity, the fact that official guidelines are published separately for each of these arrhythmias, and that they were published several years ago. To address these deficiencies, we have developed a novel pathway (Fig. 19-1) (7) for management of AF and Afl at St. Luke’s-Roosevelt Hospital Center (SLRHC), a university hospital of Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons.

The necessity to develop such a pathway at our institution was compelling, yet typical of the need at many other large medical centers, where it has become increasingly difficult for all house staff to grasp all the subtleties in the management of AF and Afl and to rapidly, efficiently, and accurately implement clinical protocols. It should be emphasized that this pathway is the opinion of our group and may differ somewhat from the published guidelines. The pathway has been designated with the acronym of RACE, which reflects the three main components in patient management: Rate control, Anti-Coagulation therapy, and Electrophysiology/anti-arrhythmic medication.

This pathway is an attempt to incorporate, in a user-friendly format, the keys to the initial diagnosis and management of these prevalent arrhythmias. This is followed by a comprehensive guideline for therapy.

Goals and Strategies in Managing Patients with Atrial Fibrillation and Atrial Flutter Based on the Race Pathway

Initial Assessment

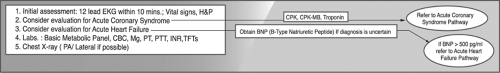

All patients should have undergone an initial assessment (Fig. 19-2) on presentation to the emergency department (ED), including 12-lead ECG (to be done within 10 minutes after arrival to the ED), history, and physician exam. Patients should be considered for evaluation of acute coronary syndrome by obtaining a blood specimen for cardiac markers and also should be considered for evaluation for acute heart failure by obtaining a BNP (β-type natriutretic peptide) level if diagnosis is uncertain. If the BNP level exceeds 500 pg/mL, patients should be treated for acute heart failure. It has been shown in multiple clinical trials that the prevalence of AF increased relative to the New York Heart Association heart failure class (8). Acute coronary syndrome and acute heart failure should be treated respectively per published guidelines and pathways (9,10).

Additional initial laboratory tests should include a basic metabolic panel, complete blood count, magnesium level, thyroid function tests, and coagulation panel. All patients should have a chest x-ray.

Assessment of Patient Hemodynamic Stability

Defining the Etiology and Pathophysiology of Atrial Fibrillation and Atrial Flutter

We have developed a systematic approach to the pathophysiology of AF and Afl (Fig. 19-4) by using acronyms that can easily be remembered by physicians, nurses, and other health care personnel:

Noncardiovascular etiology: TRAPS

T—Thyroid disease

R—Recreational drug use

A—Alcohol

P—Pulmonary disease

S—Sepsis/infection

Cardiovascular etiology: CATCH WAVE

C—Congestive heart failure

A—Acute coronary syndrome/acute myocardial infarction (MI)

TC—TaChy-brady syndrome (sick sinus syndrome)

H—Hypertension

W—Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome

A—After cardiac surgery

V—Valvular heart disease

E—mEdical noncompliance

Assessment of Duration of Atrial Fibrillation and Atrial Flutter

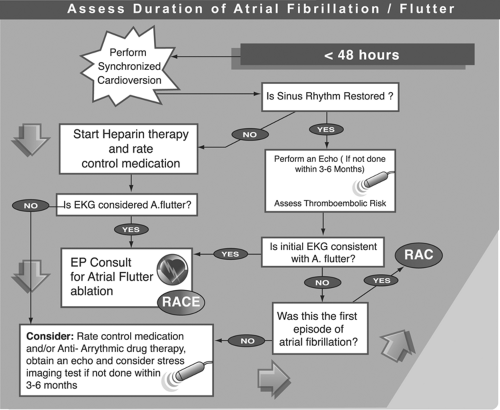

Timing the duration of atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter is sometimes difficult if the patient cannot pinpoint the starting time of their arrhythmia. It is well accepted that patients whose arrhythmia is less than 48 hours in duration can safely have a cardioversion performed (Fig. 19-5), and those with arrhythmia >48 hours may have developed atrial thrombus, which increases the risk of thromboembolic events postcardioversion.

Restoring Sinus Rhythm-Cardioversion, Electrical or Pharmacologic

Transthoracic electrical cardioversion is more successful than pharmacologic cardioversion, with an overall success rate of 75% to 93%, inversely related to the duration of AF, chest wall impedance, and left atrial size (12,13,14). The success rate for pharmacologic cardioversion in selected patients approaches 70% at best (15), and there is a risk of proarrhythmia. For this reason, we recommend electrical cardioversion.

There are two conventional positions for the electrode placement: anterior-lateral and anterio-posterior. Several studies have shown that less energy is required and a higher success rate is achieved with electrodes in the anteroposterior position (16,17). For this reason, we recommend the anteroposterior location. The energy required for cardioversion of AF is often >200 joules (18). More energy is required in obese patients and for long-standing AF. The initial energy used depends in part on the waveform of the current delivered by the defibrillation. Biphasic devices have been shown to be more effective and require less energy than monophasic devices (19).

Management of Patients with Atrial Fibrillation and Atrial Flutter of More than 48 Hours or of an Unknown Duration

When the onset of AF cannot be accurately determined or if AF is longer than 48 hours, anticoagulation should always be administered (Fig. 19-6).

The conventional approach was to recommend anticoagulation with a therapeutic international normalized ratio (INR) (2.0 to 3.0) for 3 weeks before and 4 weeks after cardioversion.

Anticoagulation prior to cardioversion can be shortened if transesophageal echo (TEE) is done and indicates the absence of thrombus in the left atrium or the left atrial appendage. The TEE guided approach has been evaluated in the Assessment of Cardioversion Utilizing Echocardiography (ACUTE) trial (20,21). With this approach, which we often employ, heparin is given immediately and concurrently with warfarin, and heparin is continued until the INR is therapeutic. Cardioversion is done immediately when the TEE suggests that there is no evidence of thrombus; warfarin is continued for at least 4 weeks depending on long-term risk.

Either intravenous unfractionated heparin or subcutaneous low-molecular-weight heparin may be used (22). Consideration of discontinuation of warfarin after 4 weeks can be made when there is no recurrence of AF and there are no stroke risk factors.

Management of Permanent Atrial Fibrillation

The nomenclature used to classify AF has been diverse (23). The published guidelines (4) suggest the classification of first detected, paroxysmal (self-terminating), persistent (not self-terminating), and permanent (Fig. 19-7).

In this regard we define permanent AF as continuous AF of longer than 7 days, with failed cardioversion or when a decision has been made not to attempt cardioversion. A patient with permanent AF will be managed with rate control and anticoagulation medication. Holter monitoring can be used to evaluate rate control. Patients whose rate control is unsuccessful should have an electrophysiology (EP) consult to consider atrioventricular (AV) nodal ablation and permanent pacemaker implantation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree