Management of Acute and Decompensated Heart Failure

Gary S. Francis

W.H. Wilson Tang

The pharmacologic management of acute heart failure has evolved considerably since the last edition of this textbook. We now have more information about the demographics of the syndrome (1), the potential hazards of routine short-term (48-hour) milrinone use (2), the availability of nesiritide to manage these patients in emergency department (ED) and step-down cardiac units (3), and a firm recognition that worsening renal function leads to poor outcomes (4). It is also now widely recognized that the design of clinical trials necessary to support the approval of new drugs for the treatment of acute heart failure is more complex than was previously believed. What outcomes should be measured in these clinical trials and when should they be measured? This has vexed both clinical investigators and regulatory agencies. With the emphasis appropriately placed on clinical outcomes rather than physiological and hemodynamic surrogate measurements, it has become increasingly difficult to successfully gain approval of new drugs for the treatment of acute heart failure. So there is good news and bad news: We know more about patients with acute heart failure but there are few new therapies available to manage these acutely ill patients.

Demographics

Approximately 1 million patients were hospitalized in 2004 in the United States with acute heart failure, costing more than $14.7 billion (5). About 50% of patients admitted with acute heart failure are readmitted within 6 months (6). Patients admitted to the hospital for acute heart failure have a 12% mortality at 30 days and a 33% mortality at 12 months (7). About 80% of patients hospitalized for heart failure are over 65 years of age (8). The combination of a rapidly expanding elderly population and the precarious financial grounding of many hospitals will continue to challenge us to develop more creative management strategies for patients with acute heart failure. Some EDs have clinical decision units where patients can be treated and stabilized over 24 to 48 hours, occasionally obviating the need for hospitalization or the need for a stay in the intensive care unit. In fact, most patients admitted to the hospital with acute heart failure in 2005 went to telemetry units with only about 15% going to the intensive care unit, according to the large ADHERE (Acute Decompensated Heart Failure National) registry (8).

Despite these demographics, it is estimated that approximately 1 million hospitalizations occur each year in the United States for treatment of acute heart failure (primary diagnosis). Another 2.5 million hospitalizations occur with heart failure as a secondary diagnosis (5). This results in about 6.5 million hospital days per year designated in the United States for acute heart failure. The admissions have increased more than 150% over the past two decades (5), undoubtedly related to growth of the aging population.

The ADHERE registry indicates that the in-hospital mortality for acute heart failure averages about 5% to 8%, with the 1-year mortality rate following hospitalization as high as 40% to 60% (9). Nearly 20% of patients admitted for treatment for acute heart failure are readmitted within 30 days of discharge. Tissue and circulatory congestion are overwhelmingly present in patients admitted with acute heart failure. Many have associated hypertension on admission. In ADHERE, only 3% of admissions have a systolic blood pressure below 90 mm Hg (9). Patients presenting with low-output heart failure are distinctly unusual, whereas preserved left ventricular ejection fration

and high blood pressure are common (∼40%). The typical patient is about 75 years old, has acute decompensation of previously stable chronic heart failure (∼70%), has had a previous hospitalization for heart failure (∼50%), and has documented coronary artery disease (57%) and hypertension (73%) (9). About 20% have atrial fibrillation. The median length of hospital stay for acute heart failure in the United States is about 4 days. In ADHERE, a blood urea nitrogen (BUN) >43 mg/dL, blood pressure <115 mm Hg, and a serum creatinine >2.75 mg/dL were independently associated with death during hospitalization (10).

and high blood pressure are common (∼40%). The typical patient is about 75 years old, has acute decompensation of previously stable chronic heart failure (∼70%), has had a previous hospitalization for heart failure (∼50%), and has documented coronary artery disease (57%) and hypertension (73%) (9). About 20% have atrial fibrillation. The median length of hospital stay for acute heart failure in the United States is about 4 days. In ADHERE, a blood urea nitrogen (BUN) >43 mg/dL, blood pressure <115 mm Hg, and a serum creatinine >2.75 mg/dL were independently associated with death during hospitalization (10).

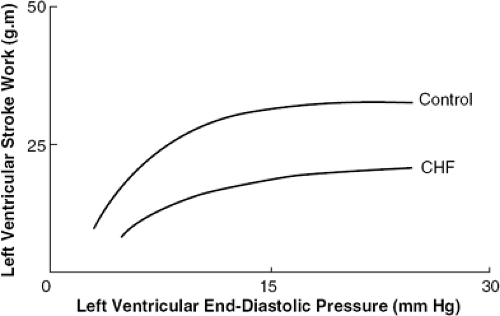

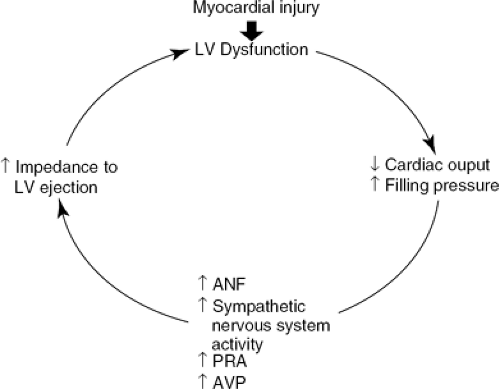

The pathophysiology of heart failure is very complex and is discussed extensively in Part I of this textbook. A fundamental feature of acute heart failure is reduced stroke volume in the setting of increased left ventricular end-diastolic pressure (Fig. 34-1). There is excessive neuroendocrine activation (Fig. 34-2), adding to heightened peripheral vascular resistance, salt and water retention, and impaired cardiac output. The relatively high blood pressure, low cardiac output, and increased resistance are ideal targets for a combination of vasodilator therapy and an intravenous loop diuretic, the usual early therapeutic strategy for patients with acute heart failure. These have remained the cornerstones of therapy but with some new twists added.

Recognition of the Patient in Need of Urgent Hospitalization: What are the Precipitating Factors?

Patients with acute heart failure are invariably short of breath, often to the point where they cannot give a detailed history due to severe dyspnea. The vast majority of patients are congested (i.e., they have findings of acute pulmonary edema, such as tachypnea, desaturation, rales, and abnormal chest X-ray, and often other tissue congestion). However, the differential diagnosis of severe dyspnea is expansive; this symptom can be due to severe asthma or an exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thus, establishing the diagnosis of heart failure can be difficult (11). At the time of presentation, usually in the ED, the patient with suspected acute heart failure should have a careful physical examination, a chest X-ray, an electrocardiogram (ECG), and possibly evaluation of plasma B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) level if the diagnosis is ambiguous. A plasma BNP level <100 pg/mL suggests an alternative diagnosis and unlikely acute heart failure (12,13). BNP as a diagnostic test is most valuable when there is uncertainty about the diagnosis in the ED setting; it is of less value in patients with more chronic, stable heart failure where false negatives may commonly occur (14).

Recently, an assay to the measurement of plasma N-terminal moiety of proBNP (NTproBNP) has also become available as a diagnostic test. The cut-off values are different than for BNP, and individual plasma NTproBNP levels may not necessarily correlate well with plasma BNP levels.

Acute Myocardial Infarction

It is important that physicians caring for patients with heart failure be thoroughly familiar with the factors that

contribute to acute decompensation (Table 34-1). Evidence of acute or intercurrent myocardial ischemia should always be sought. When hospitalization is being considered for such a patient, a 12-lead ECG should always be performed and thoroughly examined with reference to previous ECG tracings when available. Each patient must be carefully queried with regard to possible underlying myocardial ischemia, although this can be a difficult distinction to make clinically.

contribute to acute decompensation (Table 34-1). Evidence of acute or intercurrent myocardial ischemia should always be sought. When hospitalization is being considered for such a patient, a 12-lead ECG should always be performed and thoroughly examined with reference to previous ECG tracings when available. Each patient must be carefully queried with regard to possible underlying myocardial ischemia, although this can be a difficult distinction to make clinically.

Table 34-1 Factors Leading to Acute Decompensation of Heart Failure | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

It may be problematic in the elderly population to make a clear distinction between increased breathlessness from worsening heart failure and increased shortness of breath from acute myocardial ischemia. Older patients are well-known to have more atypical angina and their only manifestation of myocardial ischemia may be shortness of breath. Nevertheless, acute myocardial ischemia is a potentially reversible cause of worsening heart failure and should be investigated and excluded when possible.

Hypertension

Data from the ADHERE registry indicate that the vast majority of patients have severe hypertension on the arrival to the hospital ED with acute heart failure. Low blood pressure is distinctly uncommon. The high blood pressure may be an acute response to severe breathlessness, oxygen desaturation, and to the anxiety of acute pulmonary edema. The massive release of epinephrine and norepinephrine in patients with acute pulmonary edema (personal observations) appears to contribute significantly to the elevation in blood pressure, and diaphoresis, breathlessness, orthopnea, and diaphoresis are the rule. Prompt control of blood pressure is critically important.

Because the failing ventricle is exquisitely sensitive to afterload stress, it is possible that even a modest increase in blood pressure can initiate worsening mitral regurgitation or lead to a direct reduction in myocardial performance. Once severe pulmonary edema ensues, the anxiety and catecholamine excess often produce extreme hypertension, even in the face of what was previously thought to be remarkably reduced left ventricular function. In such cases, aggressive management of hypertension should be initiated as soon as possible. Patients with impending or obvious acute pulmonary edema who manifest breathlessness and hypertension should undergo transfer to an intensive care unit setting where intravenous nitroprusside or another IV vasodilator can be started. One should avoid using short-acting calcium-channel blockers such as sublingual nifedipine to restore normal blood pressure in this setting. Short-acting calcium-channel blockers may cause precipitous hypotension and have been associated with worsening left ventricular function (15,16). The overriding principle is that even modest elevations in blood pressure can lead to acute decompensation of chronic heart failure and therefore should be treated aggressively. In many cases, hospitalization is advised and expeditious, exquisite control of high blood pressure (and mitral regurgitation) with nitroprusside (or even sublingual or chewable nitroglycerin if hemodynamic monitoring is not available) (17) is the preferred strategy. We have less experience with nesiritide in this setting, although other experts in the field advocate its use.

New Onset of Rapid Atrial Fibrillation

New onset of atrial fibrillation is well-known to cause acute cardiac decompensation in a previously stable patient with heart failure (18). Often this is a product of inadequate control of heart rate. In virtually every large study, about 15% to 25% of patients with chronic ambulatory heart failure demonstrate atrial fibrillation (19). Although this may be well-tolerated by patients when it is chronic and the heart rate is well-controlled, the new onset of rapid atrial fibrillation is very often poorly tolerated and represents a medical emergency for some patients. When new-onset, rapid atrial fibrillation is encountered in the out-patient clinic in a patient with heart failure and worsening symptoms, the proper strategy is to transfer the patient to an acute care setting and consider direct-current (DC) cardioversion after precipitating factors such as hypokalemia have been corrected. The temptation to use intravenous diltiazem or digoxin simply to control heart rate in such patients should be avoided (20), as it is clearly more expeditious and definitive to restore normal sinus rhythm with DC cardioversion. The patient should be systemically anticoagulated with heparin, if not already adequately anticoagulated with warfarin. Class I antiarrhythmic agents should be avoided (21), as they have a high failure rate and can worsen left ventricular function. If the patient cannot

be easily cardioverted or fails to remain in sinus rhythm, control of heart rate then becomes the primary therapeutic goal. Intravenous digoxin may be helpful in acute rate control (22). For many such patients, amiodarone will become a necessary component of therapy (23). Catheter ablation is also increasingly utilized as a therapeutic strategy for prevention of acute exacerbations in refractory atrial fibrillation (24).

be easily cardioverted or fails to remain in sinus rhythm, control of heart rate then becomes the primary therapeutic goal. Intravenous digoxin may be helpful in acute rate control (22). For many such patients, amiodarone will become a necessary component of therapy (23). Catheter ablation is also increasingly utilized as a therapeutic strategy for prevention of acute exacerbations in refractory atrial fibrillation (24).

The need to acutely anticoagulate such patients is highly dependent on the urgency of correcting the rapid atrial fibrillation. If the patient has obvious hemodynamic deterioration or severe pulmonary edema, it is more prudent to directly proceed with DC cardioversion than to attempt to optimize the anticoagulant status. Most cardiologists would give intravenous heparin or low-molecular-weight heparin if there are no contraindications (25). In general, it is believed that if the atrial fibrillation is of 48 hours or less in duration, chronic anticoagulation with warfarin may not be necessary (26,27). There is increasing use of transesophageal echocardiography to rule out the presence of thrombus in the left atrial appendage prior to cardioversion in stable patients with atrial fibrillation (28). Nevertheless, a common strategy is to acutely anticoagulate such patients with intravenous heparin and simultaneously employ long-term warfarin therapy, knowing that recurrent atrial fibrillation is a distinct possibility and the presence of heart failure adds to the risk of thromboembolism in the setting of atrial fibrillation (27). Aspirin is not as effective as warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation (25).

Drug-Induced Heart Failure

A careful drug inventory should be performed in every case of acute decompensation of heart failure. Family members or close friends of the patient are valuable sources of information in this regard. A search should be made for possible recent use or increase in dose of negative inotropic drugs such as verapamil, nifedipine, diltiazem, antiarrhythmics, doxorubicin, or in some cases β-adrenergic blockers. Thiazolidinediones have also been noted to cause fluid retention. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are also well-known to provoke worsening heart failure and renal insufficiency (29). They should be considered as possible inciting factors for causing acute decompensation, given their common over-the-counter use by elderly patients. In general, β-adrenergic blockers should be continued at the present dose if the patient is taking them chronically, unless there is a severe low-output state, cardiogenic shock, or a recent increase in dose that may have precipitated worsening heart failure.

Additional Inciting Factors

Excessive alcohol consumption and endocrine abnormalities such as uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, hyperthyroidism, and hypothyroidism should always be excluded or vigorously treated when present. Concurrent infections such as pneumonia and viral illnesses commonly cause acute decompensation of previously stable heart failure and should be ruled out or treated when present. Sodium-laden antibiotics such as imipenem/cilastatin may worsen an already established volume-overloaded state. Sometimes heart failure exacerbations may occur shortly following ventricular arrhythmia, especially after firing of an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD).

Information about medication and dietary compliance should be sought. We now know that many patients do not even fill the prescriptions provided to them by physicians, and drug compliance continues to be a major problem. This is partly due to the high cost and low reimbursement for expensive new therapies. It is not uncommon for patients to fail to renew the prescription for necessary ongoing treatment therapies.

One of the most important safeguards against acute decompensation remains frequent and comprehensive out-patient assessment of the patient by the heart failure team, which should establish a certain degree of bonding and trust between the physician/team and the patient. Such a relationship cannot be assumed after a single visit or two; it requires close and continued surveillance of such fragile patients. Referral to a heart failure program may reduce both symptoms and costs (30,31,32). Daily weights, measurement of daily dietary sodium intake, and physical activity should be carefully monitored and discussed during clinic visits when the patient is stable and feeling well. Easy access to heart failure nurses and cardiologists is an essential ingredient for keeping potentially decompensated patients out of the hospital.

That being said, there have also been recent studies that challenged the perceived benefits and cost-effectiveness of heart failure disease management clinics (33,34). Most importantly, patients must be continually educated with regard to their diet, activity level, and knowledge of signs and symptoms of decompensation. Even though medical experts may not necessarily agree on criteria of when to admit an individual patient to the hospital for acute decompensation, general principles and guidelines regarding this issue should be discussed beforehand with patients and their families. Patients should be given information about the natural history of the heart failure syndrome and should understand that repeated hospitalizations for acute decompensations may sometimes be necessary.

The importance of dietary sodium restriction cannot be overstated. Often patients are given very little advice about dietary sodium restriction, and salt indiscretion is always a possible consideration as a cause for acute decompensation. For example, the most common cause of diuretic resistance is excessive dietary sodium (34). Because almost half of the patients admitted to the hospital with heart failure will be readmitted in 6 months (36), educational efforts in this regard are likely to have substantial payoff in reducing the need for subsequent hospitalizations for acute decompensation (37). As with most medical disorders, prevention is far and away the best therapeutic strategy when it can be rationally employed. The time for lengthy discussions with patients and their families is not during acute decompensation of a chronic illness but, rather, during the calm of a routine ambulatory

clinic visit when the patient is feeling reasonably well. It is at this time that serious discussion regarding diet, medications, prognosis, living wills, resuscitation status, and possible entry into clinical trials studies should be addressed in detail.

clinic visit when the patient is feeling reasonably well. It is at this time that serious discussion regarding diet, medications, prognosis, living wills, resuscitation status, and possible entry into clinical trials studies should be addressed in detail.

When to Hospitalize the Patient with Acute Heart Failure

The need for hospitalization during acute decompensation of heart failure is always somewhat judgmental and involves close interaction among the attending physician, the heart failure team, the patient, and the patient’s family (Table 34-2). The average length of stay for decompensated heart failure in the United States is 4 days (9) but it seems to be trending down. Although hospitalization is clearly the most expensive component of care for patients with heart failure, much of the expense is up-front-in the first few days of hospitalization. Therefore, keeping the patient in the hospital an extra day or two may actually be far more cost-effective than initiating highly expensive home health care to expedite premature discharge from the hospital. Readmission of prematurely discharged patients is more costly than extending the hospital stay slightly to ensure proper clinical stability. Indications for hospitalization of patients with acute decompensation include those described in the following paragraphs.

Clinical or Electrocardiographic Evidence of Acute Myocardial Ischemia or Infarction

Patients who have ECG evidence of acute myocardial ischemia should always be placed in the intensive care unit or coronary care unit. Sequential echocardiograms and serial enzymes or troponin levels should be monitored to exclude acute myocardial necrosis. In some cases, important diagnostic and prognostic information can be gained from coronary arteriography (38). In general, the superimposition of acute myocardial ischemia on severe chronic heart failure will impose an additional intolerable burden, and the possibility of reperfusion therapy (including both percutaneous techniques such as angioplasty and stenting) and coronary artery bypass surgery should always be explored.

Table 34-2 When Should Patients be Admitted to the Hospital for Acute Decompensation of Heart Failure? | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Pulmonary Edema or Increasing Respiratory Distress

Patients who are seen in the emergency room, on the hospital ward, or in the out-patient clinic with increasing dyspnea or impending pulmonary edema are candidates to be admitted to the acute care unit. Even in the absence of rales and edema, worsening shortness of breath accompanied by an increase in respiratory rate may be a forewarning of impending pulmonary edema. In some cases, further decompensation fails to develop but, nonetheless, such patients benefit from a thorough investigation as to why their symptoms are changing; they may require changes in their medical therapy. Intimate knowledge of the patient’s previous course is obviously very helpful in deciding whether to admit to the hospital.

Hypoxia Independent of Pulmonary Disease

When patients complain of shortness of breath and have hypoxemia with an oxygen saturation less than 90%, hospitalization is usually necessary. Patients with stable, ambulatory heart failure are rarely this hypoxemic during the day unless they have concomitant lung disease. Tachypnea and desaturation are signs of impending pulmonary edema and it seems prudent to admit such patients to the hospital for further care.

Severe Complicating Medical Illnesses

It is not uncommon for patients with chronic heart failure, particularly the elderly, to acutely decompensate with the development of a complicating medical illness. Pneumonia is the classic example, but even a flulike illness may precipitate acute decompensation in a patient with marginally compensated heart failure. Influenza, bacterial infection, and severely decompensated endocrine disorders such as hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism and diabetes mellitus are all indications to consider hospitalization in patients with heart failure.

Symptomatic Hypotension or Syncope

Patients with heart failure who develop symptomatic hypotension or frank syncope have a poor prognosis, even if it is determined that the symptoms are not directly a consequence of their heart disease (39). This must be distinguished from mildly symptomatic hypotension, which can occur with the use of potent diuretics, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, and β-adrenergic blockers. There is a difference between mild, intermittent lightheadedness and severe lightheadedness or syncope. If the symptoms are mild and are easily attributable to volume depletion and/or ACE inhibitor therapy, it is possible that a reduction in diuretic dose or temporary withdrawal of ACE inhibitor might be sufficient to prevent the need for hospitalization. On the other hand, when it is unclear what the nature of the lightheadedness might be, or if it is severe with the patient nearly passing

out or experiencing syncope, the consequences can be serious and the patient should be hospitalized. The risk of sudden death is high in patients with heart failure who have either cardiac or unexplained causes of syncope (40,41), and inpatient electrophysiological evaluation is often indicated. Bradyarrhythmias, tachyarrhythmias, drug-induced hypotension, and vasodepressor syncope need to be considered. In some cases, an ICD should be considered.

out or experiencing syncope, the consequences can be serious and the patient should be hospitalized. The risk of sudden death is high in patients with heart failure who have either cardiac or unexplained causes of syncope (40,41), and inpatient electrophysiological evaluation is often indicated. Bradyarrhythmias, tachyarrhythmias, drug-induced hypotension, and vasodepressor syncope need to be considered. In some cases, an ICD should be considered.

Heart Failure Refractory to Out-Patient Treatment

An experienced physician caring for the patient with heart failure can usually determine when the patient is becoming refractory to therapy. Nevertheless, this clinical dilemma can sometimes pose difficulty with regard to the need for hospi-talization and whether the patient should be admitted to the general hospital service or requires intensive care. As a general principle, when patients are simply not doing well, are anxious, and one senses apprehension on the part of the patient and the family, it is reasonable to consider hospitalization. The greater the amount of uncertainty as to the precise nature of the problem, the more likely the patient is going to benefit from hospitalization in the intensive care unit with insertion of a pulmonary artery (or Swan-Ganz) catheter and possibly an indwelling arterial catheter. Often patients will tell their physicians that they simply are unable to prevent weight gain or have increasing breathlessness and remain extremely fatigued despite an uptitration of diuretics. In many cases patients will insist that they have been highly compliant with their medications and diet, yet are declining in well-being. Clearly, some patients will benefit from short-term hospitalization, including the temporary use of intravenous vasodilators (e.g., nesiritide or nitroprusside) and/or positive inotropic support.

Often the single most intense complaint of patients with decompensated heart failure is inability to sleep soundly. The insomnia is not necessarily caused by paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea or orthopnea but, rather, is an inability to fall into a sound and sustained sleep and is accompanied by profound fatigue the following day. Sleep disorders, including central and obstructive apnea, are common in heart failure and can lead to occasional severe oxygen desaturation at night. Nocturnal O2, continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), and theophylline have all been used to treat sleep apnea in patients with heart failure. For patients with severe sleep deprivation, hospitalization is advised. Although the precise mechanism of this complaint is sometimes unclear (similar to loss of appetite), it may be a nonspecific response to markedly altered homeostasis and, in our experience, can be associated with impending acute hemodynamic decompensation.

Anasarca

Patients who present with severe peripheral edema and anasarca are generally best treated as in-patients. Continuous intravenous loop diuretics and daily metolazone are sometimes necessary, although the risk of electrolyte disturbances and renal insufficiency heightens with this regimen. In our experience it has been exceedingly difficult to manage such patients in an out-patient setting. They seem to benefit greatly from bed rest, high-dose intravenous diuretics, and temporary vasodilator or inotropic support. Bed rest alone may improve renal blood flow, thereby augmenting the diuretic and vasodilator/inotropic drug effects.

Inadequate Social Support for Safe Out-Patient Management

There are many patients for whom signs and symptoms of heart failure fail to improve because the social support and home situation are simply not suitable. Elderly patients who are unable to care for themselves, patients who cannot weigh themselves, have no access to the telephone, and have no control over their dietary needs are candidates for acute decompensation of chronic heart failure. In many cases, it is best to admit such patients to the hospital and, during the hospitalization, arrange for the patient to have a more structured out-patient support system when possible.

Management of Patients with Acutely Decompensated Heart Failure

Patients with severely decompensated heart failure can be difficult to manage. Certain goals of treatment should be considered and patients and their families should be informed of the treatment options. Following admission to the hospital, the precipitating cause of the acute decompensation should be identified and corrected when possible.

Another important goal is to improve hemodynamics. It is not necessary to normalize the hemodynamic profile of the patient with heart failure. In severely ill patients, a pulmonary artery catheter (PAC) should be inserted along with a Foley catheter and, in some cases, an arterial catheter in order to carefully assess the baseline hemodynamic picture. The primary goal should be decongestion of the patient. The results of the Evaluation Study of Congestive Heart Failure and Pulmonary Artery Catheterization Effectiveness (ESCAPE) trial suggest that, while routine use of a PAC is not indicated, there is no incremental risk of using a PAC in critically ill patients admitted for acutely decompensated heart failure (ADHF) (42). Our practice is still to use PACs in patients who are hemodynamically unstable, or in whom the left ventricular filling pressure is uncertain, or in those with oliguria or anuria. Patients in shock should also have a PAC inserted.

Routine laboratory determinations should include hemoglobin, white blood cell count, platelet count, serum electrolytes, blood sugar, liver function tests, BUN, and serum creatinine. A chest X-ray and an EKG should be performed, and usually an echo if there is no prior knowledge of myocardial performance. Depending on the clinical picture, measurement of thyroid function and arterial

blood gases (ABGs) should be considered. Patients who are tachypneic or in clinical respiratory distress in whom intubation and ventilatory support are a consideration should have ABGs checked. ABGs should also be measured prior to bilevel positive airway pressure (Bi-PAP) when one anticipates monitoring the response to therapy.

blood gases (ABGs) should be considered. Patients who are tachypneic or in clinical respiratory distress in whom intubation and ventilatory support are a consideration should have ABGs checked. ABGs should also be measured prior to bilevel positive airway pressure (Bi-PAP) when one anticipates monitoring the response to therapy.

The physical examination may be misleading (43,44,45), particularly in patients with chronic heart failure. Results from the Candesartan in Heart Failure Assessment of Reduction in Mortality and morbidity (CHARM)-preserved study demonstrate that patients with heart failure and preserved systolic function often have physical findings that are similar to patients with heart failure due to systolic dysfunction. Low blood pressure and a narrow pulse pressure correlate with a low cardiac index, but the presence or absence of rales is not particularly helpful (44). Even when the pulmonary capillary wedge pressure is in excess of 33 mm Hg, rales may be absent in patients with chronic heart failure due to the compensating changes that develop in the lungs over time. Ascites is also difficult to determine at the bedside and ultrasonography is recommended in questionable cases (45).

Diagnostic Considerations

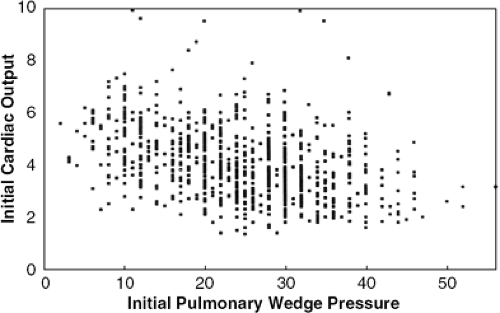

The initial cardiac output and pulmonary capillary wedge pressure in patients admitted with decompensated heart failure are highly variable (Fig. 34-3). In general, one would expect the pulmonary capillary wedge pressure to be in excess of 20 mm Hg in conjunction with a cardiac index less than 2.5 L/min/m2, but this is not always the case. Many patients demonstrate volume depletion and low cardiac filling pressures. The echo may indicate normal or supernormal ejection-phase indexes, a finding that supports the diagnosis of diastolic heart failure. Patients with diastolic heart failure often have left ventricular hypertrophy or mitral regurgitation (46,47). Elderly women with systemic hypertension and/or diabetes are typical candidates for diastolic heart failure.

Patients with so-called diastolic heart failure or heart failure with preserved left ventricular function may make up more than one-half of all patients admitted to the hospital with heart failure (48). Differentiating systolic from diastolic heart failure is important, as the treatment and natural history of the two entities may differ somewhat. The echo is the diagnostic test that will most readily differentiate these two forms of heart failure, which not infrequently coexist in patients with acute decompensation.

Initial Hemodynamic Goal

Once the baseline hemodynamic profile is determined, a specific therapeutic plan should be formulated and discussed with the patient and family when appropriate (49). Today, most patients admitted to the hospital with heart failure are already receiving ACE inhibitors, digitalis, and high doses of diuretics; many are also receiving β-adrenergic blockers. When the diagnosis of heart failure is secure and all reversible causes have been excluded, it can be presumed that the current exacerbation is caused by the inexorable progression of heart failure over time. Because patients with decompensated heart failure are almost always tachypneic and short of breath, the primary goal should be to reduce pulmonary capillary filling pressure. This is normally done with an intravenous loop diuretics with or without an intravenous vasodilator such as nitro-prusside or nesiritide.

Diuretics

High doses of intravenous loop diuretics are indicated (50) because oral absorption may be impaired in decompensated heart failure (51). Both venodilator (52) and direct vasoconstrictor (53) vascular effects of intravenous furosemide may be observed, but in most instances sodium and water excretion is the dominant effect of diuretic therapy. The choice of the loop diuretic varies substantially among physicians. Furosemide (40 to 120 mg intravenously), bumetanide (0.5 to 2 mg intravenously as a bolus), or torsemide (20 to 40 mg intravenously) may be preferred. When patients are truly refractory to regularly scheduled, high-dose intravenous loop diuretics, it maybe prudent to consider giving supplemental intravenous chlorothiazide (500 to 1,000 mg intravenously over 15 minutes) before administering the loop diuretic. This will provide synergy between the diuretics (54,55). As the extracellular volume decreases, a complex array of neuroendocrine changes occur that can stimulate sodium and water reabsorption at sites in the kidney distal to the diuretic action. Following chronic use of loop diuretics, adaptive changes in the distal tubule occur, triggering increased sodium reabsorption. Diuretics such as thiazides or metolazone that are active at the distal tubule may block this compensatory response and may retard the development of distal tubular hypertrophy. These observations form the basis of combination diuretic therapy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree