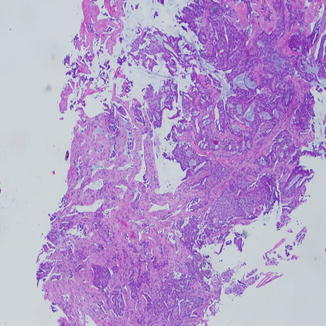

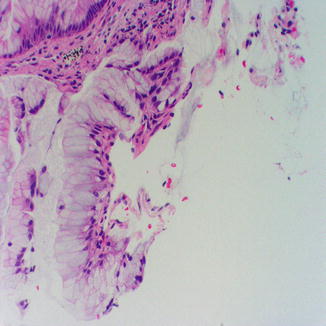

Fig. 8.1

Adenocarcinoma in situ at the interface with normal lung shows an abrupt transition, unlike reactive type II pneumocytes where they blend gradually with normal type I. The cytologic atypia is higher than that seen in reactive epithelium, and there is no evidence of invasion or host response (lymphocytic infiltrate)

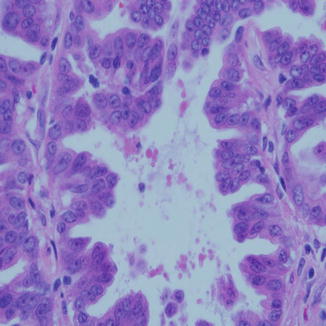

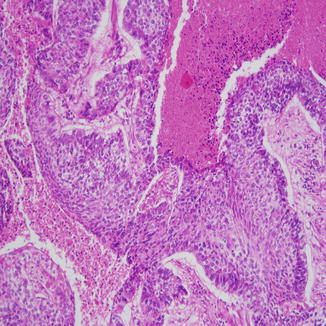

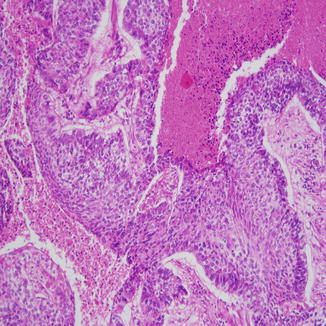

Fig. 8.2

Invasive adenocarcinoma of the lung on a small biopsy showing acini of tumor with lumen formation infiltrating into the lung parenchyma. Blue mucin can be seen easily into lumens

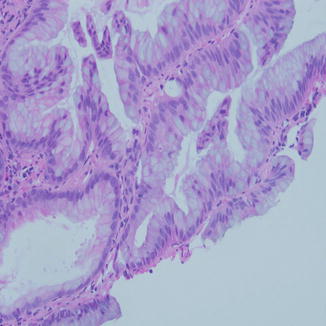

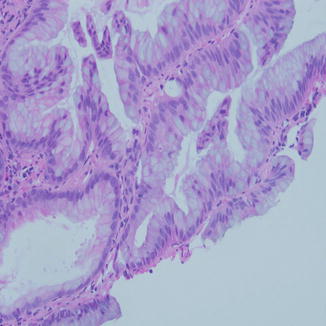

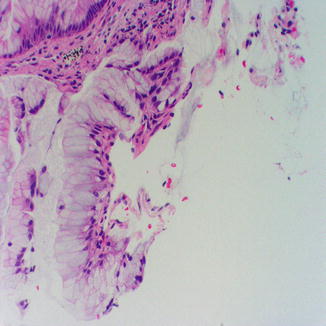

Fig. 8.3

Papillary carcinoma of the lung is comprised of papillary fronds with delicate fibrovascular cores and loss of polarity of the nuclei. High-grade nuclear features are the norm. Sometimes the feature is partially present in another pattern

Diagnosis on small biopsies of well-differentiated adenocarcinoma is fraught with several difficulties; distinguishing this tumor from reactive type II pneumocytes, especially in areas around fibrosis and chronic inflammation, is one that is underappreciated in lung pathology. Looking for cilia and cytologic features is very important before making the diagnosis of cancer. The history of smoking, recent weight loss, and the radiologic findings are some of the helpful findings to support the diagnosis of malignancy in those cases.

A tumor formerly known as mucinous bronchioloalveolar carcinoma is now called mucinous adenocarcinoma as these tumors have a different presentation and immunohistochemical and molecular profile than AIS. These tumors could present as a multifocal disease, pneumonia-like pattern, or as a solitary irregular area of consolidation on imaging studies. They are characterized by a copious amount of secreted mucin which patients would cough out. The cells usually have enlarged nuclei with irregular nuclear contours but are basally located with an abundant amount of columnar cytoplasm (Fig. 8.4). They differ from non-mucinous type in their reactivity to CK20 and variable staining with CK7 and TTF-1; the latter two are consistently positive in AIS. Mucinous adenocarcinoma has high level of Kras mutations as it is also associated with history of smoking [3]. For those reasons, the biology and prognosis of mucinous adenocarcinoma are thought to represent a different entity from AIS even though they were previously lumped together under the term bronchioloalveolar carcinoma.

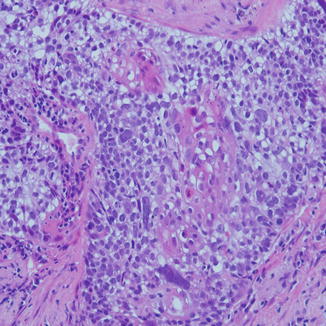

Fig. 8.4

Mucinous adenocarcinoma in a small biopsy is difficult to recognize because of the overlap with bronchial epithelium exhibiting goblet cell hyperplasia. Lack of cilia and the network of mucinous epithelium along with the tufting seen here are strong evidence to the nature of the lesion, especially in the setting of large mass in the lung

Mucinous adenocarcinoma should always be differentiated from metastatic counterparts from other organs such as breast colloid carcinoma, pancreas, and colon in addition to gynecologic tumors with similar morphology. Reactivity to such markers as CDX2 is helpful in this regard, but the clinical correlation with lesions or history of carcinoma in these organs is always helpful [4, 5].

Small biopsies from mucinous adenocarcinoma can be difficult to diagnose. However, the presence of tufting and nuclear membrane irregularity on cytologic material are helpful features to make such diagnosis (Fig. 8.5). Mucinous carcinoma in situ is extremely rare and most of mucinous carcinomas of the lung are invasive by the time they are being diagnosed.

Fig. 8.5

Minute fragment of mucinous adenocarcinoma in a needle core biopsy of the lung showing tufting of the mucinous epithelium and lack of cilia

The majority of patients with adenocarcinoma are smokers, but the occurrence of AIS is common in nonsmokers. The lesion starts as a small precancerous lesion known as atypical adenomatous hyperplasia (AAH) where atypical cells with early molecular genetic aberration similar to those in AIS appear in the lung. Their size is usually less than 5 mm in diameter and could be encountered in resected lungs for any other reason, and they are considered as “field defect.”

By immunohistochemistry the majority of adenocarcinomas react positively to thyroid transcription factor (TTF-1) in about 80 % of cases. Another marker is napsin A, which stains surfactant producing cells as it also stains other tumors from the kidney, thyroid, and others [6]. These two markers are very useful in differentiating poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma from poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma, along with other markers for squamous cell differentiation as p63 and/or CK5/6. Recently, cocktails of these markers using different chromogens have been used in performing the stains on limited material. TTF-1 and napsin A could be combined using alkaline phosphatase (brown color and nuclear pattern) combined with horseradish or victor red (red color and cytoplasmic). Both could stain the same cells concurrently. The same could be done with p40 (nuclear) and CK5/6 (cytoplasmic) [7]. Mucin stain could also be used as a cheap and quick method in identifying intracellular mucin secretion and as a proxy for glandular differentiation.

On the molecular level, adenocarcinomas express higher frequency of Kras mutation, especially in smokers (30 %) as compared to nonsmokers (5 %).

The revolutionary discovery of epithelial growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutation in patients with adenocarcinoma (especially women nonsmokers from Asian descent) and the introduction of tyrosine kinase inhibitor chemotherapy made it imperative to identify patients with adenocarcinoma and to test these patients for the mutation. Other mutations such as EML 4-ALK mutation which is encountered less frequently than EGFR ones opened the door for more molecular testing and targeted therapy to these patients [8].

Squamous Cell Carcinoma

This is the second most common carcinoma in the lung. It is characterized by squamous differentiation with keratinization and formation of intercellular bridges corresponding to desmosomes on the ultrastructural level.

Over 90 % of squamous cell carcinomas occur in smokers. They are usually preceded by squamous metaplasia and dysplasia of the bronchial lining epithelium before progressing to squamous cell carcinoma in situ and finally into invasive squamous cell carcinoma. The tumor is usually centrally located; however, peripherally located tumors occur in a minority of cases.

On imaging, the central location of tumor and proximity to relatively large bronchi and bronchioles are associated with obstruction and occlusion with the resultant collapse or atelectasis of lung segments distal to the tumor. These tumors could also extend to the hilar or mediastinal lymph nodes appearing as masses in those areas. Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common tumor to cavitate resulting in a thick-walled cavity with areas of central lucency. When they occur in the superior sulcus of the lung, they are called Pancoast tumor. They could erode into the posterior ribs and could cause Horner’s syndrome.

Grossly, the tumor is white or gray with black carbon pigments throughout. They may show necrotic center with stellate-shaped periphery. There may be central necrosis or polypoid growth pattern, especially when the tumor extends into the bronchial lumen.

Microscopically, the tumor shows keratin formation, the amount of which is proportionate to the degree of differentiation; more differentiated tumors have more keratinization. The cells have large dark nuclei and a moderate amount of waxy eosinophilic cytoplasm. Sometimes the cells have a smaller amount of cytoplasm with dark and amphophilic color and peripheral palisading similar to that of basal cell carcinoma of the skin, which invoked the name basaloid variant of squamous cell carcinoma (Fig. 8.6). When the cells show cytoplasmic clearing, this would indicate clear cell change and the name clear cell variant is used (Fig. 8.7). When the cells still get smaller but with distinct borders, prominent nucleoli, and intercellular bridges, small cell variant is rendered in the diagnosis. This needs to be distinguished from small cell carcinoma or combined small cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma based on the presence or absence of neuroendocrine differentiation.

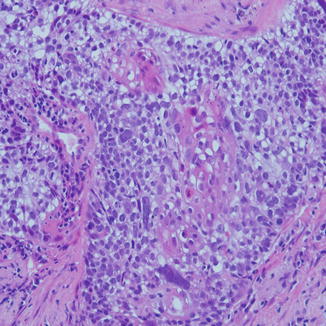

Fig. 8.6

Basaloid squamous cell carcinoma with peripheral palisading of the basal layer, which has darker nuclei and high N/C ratio. These cells can look similar to small cell carcinoma on cytologic material

Fig. 8.7

Squamous cell carcinoma with clear cell pattern. There is an island of squamous differentiation in the middle

Immunohistochemistry is very helpful in differentiating poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma from other types of carcinomas. Squamous cell carcinoma is usually positive for pancytokeratin, high molecular weight cytokeratin, and CEA. Two specific markers that are frequently used in practice for squamous differentiation are p63 and CK5/6. A more specific clone of p63 came into use recently and is known as p40 [7].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree