M-O

Metabolic syndrome

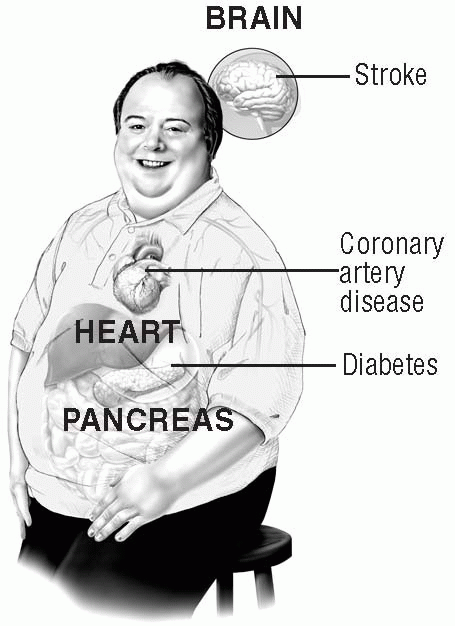

Metabolic syndrome—also called syndrome X, insulin resistance syndrome, dysmetabolic syndrome, and multiple metabolic syndrome—is a cluster of conditions characterized by abdominal obesity, high blood glucose (type 2 diabetes mellitus), insulin resistance, high blood cholesterol and triglycerides, and high blood pressure. More than 22% of people in the United States meet three or more of these criteria, raising their risk of heart disease and stroke and placing them at high risk for dying of myocardial infarction.

CAUSES AND INCIDENCE

Abdominal obesity is a strong predictor of metabolic syndrome because abdominal fat tends to be more resistant to insulin than fat in other areas. This increases the release of free fatty acids into the portal system, leading to increased apolipoprotein B, increased low-density lipoprotein (LDL), decreased high-density lipoprotein (HDL), and increased triglyceride levels. As a result, the risk of cardiovascular disease is increased.

Type 2 diabetes mellitus is a risk factor because a hallmark for metabolic syndrome is a fasting glucose level of greater than 110 mg/dl. People with diabetes develop atherosclerotic heart disease at a younger age than other people. They’re also at increased risk for macrovascular disease (ischemic heart disease, stroke, and peripheral vascular disease). Diabetes is a coronary heart disease risk equivalent.

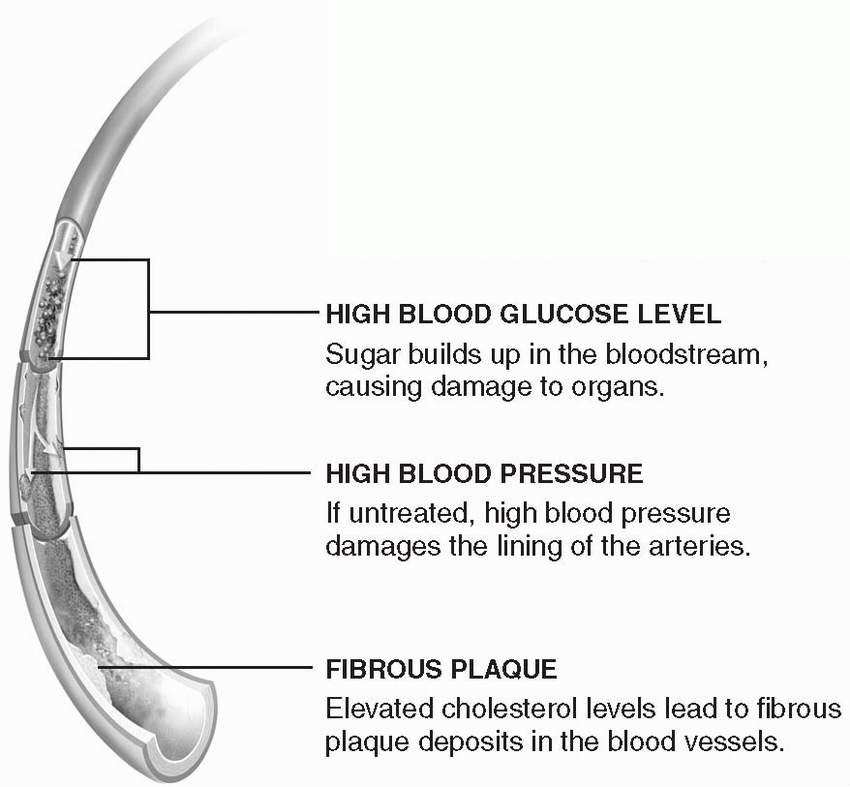

Insulin resistance and dyslipidemia are also risk factors because insulin resistance leads to hyperinsulinemia, hyperglycemia, abnormal glucose and lipid metabolism, damaged endothelium, and cardiovascular disease. Insulin is also responsible for reducing the amount of free fatty acids in the liver. However, people with insulin resistance have an increased amount of free fatty acids reaching the liver, resulting in high triglyceride and LDL levels and producing an abnormal endothelium and atherosclerosis.

High blood pressure is a risk factor because the combination of insulin resistance, hyperinsulinemia, and abdominal obesity leads to hypertension and its harmful cardiovascular effects. Moreover, insulin resistance promotes salt sensitivity in people with high blood pressure. Research also indicates that there may be a genetic predisposition to metabolic syndrome.

In normal digestion, the intestines break down food into its basic components, one of which is glucose. Glucose provides energy for cellular activity, while excess glucose is stored in cells for future use. Insulin, a hormone secreted in the pancreas, guides glucose into storage cells. However, in people with metabolic syndrome, insulin is less able to carry glucose into the cells. The body then generates excess insulin to overcome this resistance. This excess in quantity and force of insulin causes damage to the lining of the arteries, promotes fat storage deposits, and prevents fat breakdown. This series of events can lead to diabetes, blood clots, and coronary events. (See Patient teaching aid: Metabolic syndrome, page 118.)

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Assessment commonly reveals a history of hypertension, abdominal obesity, sedentary lifestyle, poor diet, and a family history of metabolic syndrome. Physical findings include abdominal obesity (waist measurement greater than 40″ [101.6 cm] in men and 35″ [88.9 cm] in women), blood pressure of 130/85 mm Hg or higher, and a fasting blood glucose level that’s 100 mg/dl or higher. The patient may feel tired, especially after eating, and may have trouble losing weight.

COMPLICATIONS

• Coronary artery disease

• Diabetes mellitus

• Hyperlipidemia

• Stroke

• Premature death

DIAGNOSIS

• Blood studies commonly indicate elevated blood glucose levels, hyperinsulinemia, and elevated serum uric acid.

• Use of lipid profile studies reveal elevated LDL levels, low HDL levels, and elevated triglycerides.

• Further diagnostic procedures are nonspecific, but may be performed to detect hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and hyperinsulinemia.

TREATMENT

Lifestyle modification, focusing on weight reduction and exercise, is an important part of the treatment regimen. Modest weight reduction through diet and exercise considerably improves hemoglobin A1c levels, reduces insulin resistance, improves blood lipid levels, and decreases blood pressure—all elements of metabolic syndrome. Recent studies have shown that in patients with impaired glucose tolerance, losing an average of 7% of body weight reduced the risk of developing type 2 diabetes by 58%. To improve cardiovascular health, a diet rich in vegetables, fruits, whole grains, fish, and low-fat dairy products combined with regular exercise is recommended. Moreover, nutrient-dense, low-energy foods should replace low-nutrient, high-calorie foods. Meal replacements and shakes may also

reduce risk factors for metabolic syndrome and improve weight loss. (See Therapeutic lifestyle-changes diet.)

reduce risk factors for metabolic syndrome and improve weight loss. (See Therapeutic lifestyle-changes diet.)

PATIENT-TEACHING AID: METABOLIC SYNDROME

Dear Patient:

Your physician has determined that you have metabolic syndrome (sometimes called insulin resistance syndromeor syndrome X). This handout will help you understand metabolic syndrome and how it can affect you.

|

▪ Although the syndrome isn’t completely understood yet, it’s clear that people with metabolic syndrome have an increased risk of serious health problems, including coronary artery disease, stroke, and diabetes.

▪ Usually, to be diagnosed with metabolic syndrome, you’ll have at least three of the following: abdominal obesity (a waist measurement larger than 40 inches for men, 35 inches for women); high blood pressure (130/85 mm Hg or higher); insulin resistance, in which the body doesn’t use insulin properly (fasting blood glucose level of 110 mg/dl or higher); and an abnormal cholesterol profile (an increased triglyceride level or a high-density lipoprotein level of less than 40 mg/dl in men, 50 mg/dl in women).

▪ The biggest risk factors for metabolic syndrome seem to be physical inactivity and overweight, although aging and genetic predisposition may be involved.

▪ Insulin resistance also seems central to the development of metabolic syndrome. Normally, food is absorbed into the bloodstream as glucose and other substances, and insulin released by the pancreas carries glucose out of the blood and into the cells to be used for energy. When insulin isn’t working properly, glucose can’t be used normally. Some of the glucose doesn’t get to the cells that need it, staying instead in the bloodstream. An increased blood glucose level can lead to diabetes and organ damage.

▪ To reduce the risk that metabolic syndrome will lead to cardiovascular disease, stroke, or diabetes, lose weight if needed (so your body mass index is less than 25 kg/m2), don’t smoke, get at least 30 minutes of moderate exercise most days of the week, and eat a healthy diet low in saturated fat, trans fat, and cholesterol.

|

THERAPEUTIC LIFESTYLE-CHANGES DIET

The therapeutic lifestyle-changes diet is low in saturated fats and cholesterol to reduce blood cholesterol levels and help prevent heart disease and its complications. This diet recommends consuming:

▪ less than 7% of the day’s total calories as saturated fat (including trans fat)

▪ 25% to 35% of the day’s total calories as fat

▪ less than 200 mg of dietary cholesterol daily

▪ no more than 2,400 mg of sodium daily

▪ just enough calories to achieve or maintain a healthy weight and cholesterol level.

Also, for most people, it recommends moderate exercise for at least 30 minutes, 3 or 4 days weekly.

If blood cholesterol isn’t lowered enough by following this diet, the practitioner may recommend increasing the amount of soluble fiber in the diet or adding cholesterol-lowering foods. These include margarines and salad dressings that contain plant sterol esters or plant stanol esters. If the low-density lipoprotein level still isn’t lowered enough, the patient may need a cholesterol-lowering drug.

Source: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Available at www.nhlbi.nih.gov/chd/lifestyles.htm and www.nhlbi.nih.gov/cgi-bin/chd/step2intro.cgi.

A regular exercise program of moderate physical activity in addition to dietary modifications promotes weight loss, improves insulin sensitivity, and reduces blood glucose levels. According to the Surgeon General’s Report on Physical Activity and Health, a person should exercise moderately for at least 30 minutes on most or all days of the week. The exercise program should be designed to improve cardiovascular conditioning, increase strength through resistance training, and improve flexibility.

Some patients may need drug treatment for metabolic syndrome in addition to changes in diet and exercise. They include:

• patients with a body mass index (BMI) of 27 kg/m2 or greater plus other risk factors, such as diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia

• patients with a BMI of 30 kg/m2 or greater

• patients who haven’t had significant weight loss after 12 weeks.

Surgical treatment of obesity, such as through gastric bypass procedures, produces a greater degree and duration of weight loss than other therapies and improves or resolves most aspects of metabolic syndrome. Candidates for surgical intervention include patients with a BMI greater than 40 kg/m2 or those with a BMI greater than 35 kg/m2 and obesity-related medical

conditions. Gastric bypass procedures produce permanent weight loss in most patients.

conditions. Gastric bypass procedures produce permanent weight loss in most patients.

Drugs

• Orlistat (Xenical) to decrease the absorption of dietary fat by inhibiting pancreatic lipase, which is needed for fat breakdown and absorption. (When obese patients take orlistat while dieting, they achieve greater weight loss and serum glucose control than by dieting alone. Because the absorption of fat-soluble vitamins is reduced, the patient may need vitamin supplementation.)

• Sibutramine (Meridia) to inhibit the reuptake of serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine; increase the satiety-producing effects of serotonin; and reduce the drop in metabolic rate that commonly occurs with weight loss

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

• Monitor the patient’s blood pressure and blood glucose, blood cholesterol, and insulin levels.

• Because longer lifestyle modification programs tend to improve weight loss maintenance, encourage a patient with metabolic syndrome to start an exercise and weight loss program with a friend or family member. Help him explore options, and support his efforts.

• To improve compliance, schedule frequent follow-up with the patient. At each appointment, review his food diaries and exercise logs. Be positive, and promote his active participation and partnership in his treatment plan.

• A patient planning gastric bypass surgery should receive psychological and nutritional counseling before and after surgery to help with diet and lifestyle changes.

Mitral insufficiency

Mitral insufficiency—also known as mitral regurgitation—occurs when a damaged mitral valve allows blood from the left ventricle to flow back into the left atrium during systole. (See Types of valvular heart disease, page 8.)

CAUSES AND INCIDENCE

Damage to the mitral valve can result from rheumatic fever, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, mitral valve prolapse, myocardial infarction, severe left-sided heart failure, ruptured chordae tendineae, or infective endocarditis. In older patients, mitral insufficiency may occur because the mitral annulus has become calcified. The cause is unknown, but it may be linked to a degenerative process.

Blood from the left ventricle flows back into the left atrium during systole, causing the atrium to enlarge to accommodate the backflow. As a result, the left ventricle also dilates to accommodate the increased blood volume from the atrium and to compensate for diminishing cardiac output. Ventricular hypertrophy and increased end-diastolic pressure result in increased

pulmonary artery pressure (PAP), eventually leading to left-sided and right-sided heart failure.

pulmonary artery pressure (PAP), eventually leading to left-sided and right-sided heart failure.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Depending on the severity of the disorder, the patient may be asymptomatic or complain of trouble breathing when lying flat, shortness of breath with exertion, fatigue, weakness, weight loss, chest pain, and palpitations. Inspection may reveal jugular vein distention with an abnormally prominent a wave. Peripheral edema may be present.

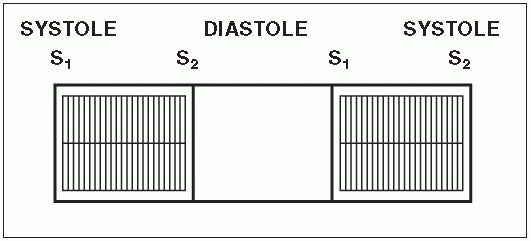

Auscultation may detect a soft S1 that may be buried in the systolic murmur. A grade 3 to 6 or louder holosystolic murmur, most characteristic of mitral insufficiency, is best heard at the apex. A split S2 and a low-pitched S3 may also be heard. The S3 may be followed by a short, rumbling diastolic murmur. A fourth heart sound may be heard in patients who have severe mitral insufficiency of recent onset and who are in normal sinus rhythm. (See Identifying the murmur of mitral insufficiency.)

Auscultation of the lungs may reveal crackles if the patient has pulmonary edema. Palpation of the chest may disclose a regular pulse rate with a sharp upstroke. A systolic thrill at the apex may be palpable. When the left atrium is markedly enlarged, it may be palpable along the sternal border late during ventricular systole. It resembles a right ventricular lift. Abdominal palpation may reveal hepatomegaly if the patient has right-sided heart failure.

COMPLICATIONS

• Ventricular hypertrophy and increased end-diastolic pressure

• Increased PAP

• Left- and right-sided heart failure

• Pulmonary edema

• Cardiovascular collapse

DIAGNOSIS

• Cardiac catheterization is used to detect mitral insufficiency with increased left ventricular end-diastolic volume and pressure, increased left atrial and pulmonary artery wedge pressures, and decreased cardiac output. Cardiac catheterization can resolve discrepancies between the clinical presentation of a patient’s symptoms and the results of a noninvasive transthoracic echocardiogram. If coronary artery disease is suspected, the need for coronary artery by-pass graft surgery can be determined.

• Chest X-rays show left atrial and ventricular enlargement, pulmonary vein congestion, and calcification of the mitral leaflets in patients with long-standing mitral insufficiency and stenosis.

• Echocardiography reveals abnormal motion of the valve leaflets, left atrial enlargement, and a hyperdynamic left ventricle.

• Transesophageal echocardiogram can establish the severity of mitral regurgitation and the need for surgical repair or replacement.

• Electrocardiography may show left atrial and ventricular hypertrophy, sinus tachycardia, and atrial fibrillation.

TREATMENT

The nature and severity of symptoms determine treatment for a patient with valvular heart disease. For example, he may need to restrict activities to avoid extreme fatigue and dyspnea. If the patient has severe signs and symptoms that can’t be managed medically, he may need open-heart surgery with cardiopulmonary by-pass for valve replacement.

Drugs

• Antibiotics to treat infective endocarditis

• Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or beta-adrenergic blockers to treat heart failure

• Digoxin (Lanoxin), calcium channel blockers, or beta-adrenergic blockers to treat arrhythmias

• Anticoagulants (warfarin [Coumadin]) to prevent thrombus formation around diseased, repaired, or replaced valves

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

• Provide periods of rest between periods of activity to prevent excessive fatigue.

• To reduce anxiety, let the patient express his concerns about the effects of activity restrictions on his responsibilities and routines. Reassure him that the restrictions are temporary.

• Keep the patient on a low-sodium diet; consult with the dietitian to ensure that the patient receives as many favorite foods as possible during the restriction.

• Monitor the patient for left-sided heart failure, pulmonary edema, and adverse reactions to drug therapy. Provide oxygen to prevent tissue hypoxia as needed.

• If the patient has surgery, monitor him postoperatively for hypotension, arrhythmias, and thrombus formation.

• Monitor the patient’s vital signs, arterial blood gas levels, intake and output, daily weight, blood chemistry results, chest X-rays, and pulmonary artery catheter readings.

• Teach the patient about diet restrictions, medications, signs and symptoms that should be reported, and the importance of consistent follow-up care.

• Explain all tests and treatments.

• Make sure the patient and his family understand the need to comply with prolonged antibiotic therapy and follow-up care.

• Tell the parents or patient to stop the drug and call the practitioner immediately if the patient develops a rash, fever, chills, or other signs or symptoms of allergy at any time during penicillin therapy.

• Instruct the patient and his family to watch for and report early signs and symptoms of heart failure, such as dyspnea and a hacking, nonproductive cough.

Mitral stenosis

In patients with mitral stenosis, valve leaflets become diffusely thickened by fibrosis and calcification. The mitral commissures fuse, the chordae tendineae fuse and shorten, the valvular cusps become rigid, and the apex of the valve becomes narrowed, obstructing blood flow from the left atrium to the left ventricle. (See Types of valvular heart disease, page 8.)

CAUSES AND INCIDENCE

Mitral stenosis most commonly results from rheumatic fever. It also may be related to congenital anomalies.

As a result of obstructive changes, left atrial volume and pressure increase and the atrial chamber dilates. The increased resistance to blood flow causes pulmonary hypertension, right ventricular hypertrophy and, eventually, right-sided heart failure. Pulmonary hypertension increases transudation of fluid from pulmonary capillaries, which can cause fibrosis in the alveoli and pulmonary capillaries. This action reduces vital capacity, total lung capacity, maximal breathing capacity, and oxygen uptake per unit of ventilation. Also, inadequate filling of the left ventricle reduces cardiac output.

Mitral stenosis occurs twice as often in women as in men.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Patients with mild mitral stenosis may have no symptoms. Those with moderate to severe mitral stenosis may have a history of exertional dyspnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, orthopnea, weakness, fatigue, and palpitations. A dry cough and dysphagia may occur because of an enlarged left atrium or bronchus. The presence of hemoptysis suggests rupture of pulmonary-bronchial venous connections.

Inspection may reveal peripheral and facial cyanosis, particularly in severe cases. The patient’s face may

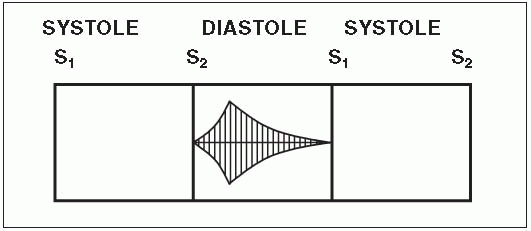

appear pinched and blue, and she may have a malar rash. Jugular vein distention and ascites may be present in a patient with severe pulmonary hypertension or tricuspid stenosis. Palpation may reveal peripheral edema, hepatomegaly, and a diastolic thrill at the cardiac apex. Auscultation may reveal a loud S1 or opening snap and a diastolic murmur at the apex, along the left sternal border, or at the base of the heart. (See Identifying the murmur of mitral stenosis.) In a patient with pulmonary hypertension, S2 is commonly accentuated, and the two components of S2 are closely split. A pulmonary systolic ejection click may be heard in a patient with severe pulmonary hypertension. Crackles may be heard when the lungs are auscultated.

appear pinched and blue, and she may have a malar rash. Jugular vein distention and ascites may be present in a patient with severe pulmonary hypertension or tricuspid stenosis. Palpation may reveal peripheral edema, hepatomegaly, and a diastolic thrill at the cardiac apex. Auscultation may reveal a loud S1 or opening snap and a diastolic murmur at the apex, along the left sternal border, or at the base of the heart. (See Identifying the murmur of mitral stenosis.) In a patient with pulmonary hypertension, S2 is commonly accentuated, and the two components of S2 are closely split. A pulmonary systolic ejection click may be heard in a patient with severe pulmonary hypertension. Crackles may be heard when the lungs are auscultated.

COMPLICATIONS

• Pulmonary hypertension

• Pulmonary hemorrhage

• Pulmonary fibrosis

• Thrombi

• Infarction of the brain, kidneys, spleen, or limbs (most common in patients with arrhythmias)

DIAGNOSIS

• Echocardiography is the preferred diagnostic test for mitral stenosis.

• Transthoracic echocardiography is useful in establishing the diagnosis, determining the shape of the valve leaflets, and assessing the hemodynamic response to exercise.

• Transesophageal echocardiography will identify thrombus in the left atrium, a potential source of embolic stroke.

• Cardiac catheterization shows a diastolic pressure gradient across the valve. It also shows elevated pulmonary artery wedge pressure (greater than 15 mm Hg) and pulmonary artery pressure in the left atrium with severe pulmonary hypertension. It detects elevated right ventricular pressure, decreased

cardiac output, and abnormal contraction of the left ventricle.

cardiac output, and abnormal contraction of the left ventricle.

• Cardiac catheterization can resolve discrepancies between the clinical presentation of a patient’s symptoms and the results of a noninvasive transthoracic echocardiogram. If coronary artery disease is suspected, the need for coronary artery by-pass graft surgery can be determined.

• Chest X-rays show left atrial and ventricular enlargement (in patients with severe mitral stenosis), straightening of the left border of the cardiac silhouette, enlarged pulmonary arteries, dilation of the upper lobe pulmonary veins, and mitral valve calcification.

• Electrocardiography reveals left atrial enlargement, right ventricular hypertrophy, right axis deviation and, in 40% to 50% of cases, atrial fibrillation.

TREATMENT

Treatment for the patient with valvular heart disease depends on the nature and severity of associated symptoms. In a young patient with asymptomatic mitral stenosis, endocarditis prophylaxis is important.

If the patient is symptomatic, treatment varies. Heart failure requires bed rest, medication, a sodium-restricted diet and, for acute cases, oxygen.

If hemoptysis develops, the patient requires bed rest, a sodium-restricted diet, and a diuretic to decrease pulmonary venous pressure. Embolization mandates an anticoagulant along with symptomatic treatments.

A patient with severe, medically uncontrollable symptoms may need open-heart surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass for valve replacement or repair. Percutaneous balloon valvuloplasty may be used in a young patient who has no calcification or subvalvular deformity, in the symptomatic pregnant woman, and in an elderly patient with end-stage disease who can’t withstand general anesthesia. This procedure is performed in the cardiac catheterization laboratory.

Drugs

• Beta-adrenergic blockers or calcium channel blockers to control heart rate

• Anticoagulants to prevent thrombus formation around diseased, repaired, or replaced valves

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree