Long-Term Uses of Mechanical Circulatory Support Devices

Joseph C. Cleveland Jr.

OVERVIEW OF THE MECHANICAL CIRCULATORY SUPPORT LANDSCAPE

Mechanical circulatory support (MCS) has undergone a very rapid evolution during the past decade. Heart failure continues to increase at a rate which predicts that nearly 8 million Americans will have a diagnosis of heart failure by 2030, which represents a 25% increase in prevalence (1). Given that at most 2,300 donor hearts become available for transplantation in the United States each year, one can appreciate this huge supply/demand problem that exists for treating heart failure (2). The concept of treating patients with a permanent, lifetime replacement of a failing left ventricle (LV) is not a new concept. The development of an “artificial heart” or permanent left ventricular assist device (LVAD) began in lockstep with the idea of the Apollo Space Missions in the 1960s. However, LVADs have just recently—within the past 5 years—proved efficacious as a viable long-term replacement therapy. Coupled with this exponential rise in heart failure, the concept of long-term or destination therapy (DT) has evolved to be an accepted practice for a patient with advanced heart failure at present.

DT: DEFINITION, INDICATIONS, AND EVOLUTION

DT is defined as the use of an LVAD for lifelong support in a patient who is ineligible for cardiac transplantation. Usually, advanced age (>65-70 years of age) and comorbid conditions which preclude cardiac transplantation are responsible for deciding that a particular patient is eligible for DT. It must be emphasized that medical therapy is quite successful and appropriate for patients with lesser degrees of heart failure (New York Heart Association [NYHA Class I-III]). However, there has been little improvement in survival for patients with advanced (NYHA Class IV) heart failure with medical therapy. Indeed, the pivotal landmark study, the REMATCH trial which was published in 2001, is a strong example of the contrast between medical therapy and long-term LVAD use (3). This study prospectively randomized 129 patients who were not candidates for heart transplantation to either best medical therapy or treatment with a HeartMate XVE LVAD. Arguably, the patients studied were the sickest group of patients entered into a clinical trial in the history of medicine. Nearly three-fourths of the patients were inotrope dependent, and all patients were in NYHA Class IV heart failure. The LVAD group had a much improved survival rate and quality of life compared to the medical group; indeed 23% of the LVAD patients were alive at 2 years follow-up versus only 8% of the medical group. Further, scores on quality of life indices such as the SF-36 and Beck Depression Index were significantly better in the LVAD group. Based on these data, the HeartMate XVE pump was approved for DT in 2002 by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and the indications in the REMATCH trial led to the National Coverage Decision (NCD) by Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), which outlined the indications for DT.

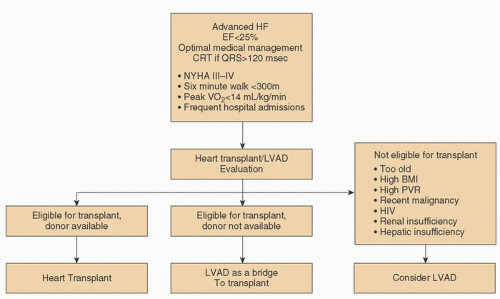

While REMATCH demonstrated that LVADs were superior to medical therapy for advanced heart failure patients without a cardiac transplantation option, there were many important “pearls” gleaned from this trial. Firstly, there was a sobering early mortality rate from patients who were past the point of recovery. For example, patients who were mechanically ventilated or patients with anuric renal failure, hepatic failure, or evidence of severe biventricular failure/cardiogenic shock at the time of implantation all died very early, and one could argue that they derived no benefit from this therapy. Thus, patient selection and earlier intervention (before irreversible cardiogenic shock develops) for LVAD were an important lesson from REMATCH. Secondly, despite extensive bench testing of the HeartMate XVE pump, this pump predictably failed between 18 and 24 months from bearing wear, cam failure, or rapid failure of the bioprosthetic valves that were inside the pump. In brief, the XVE was not going to be a long-term pump as configured, as mechanical failure of the pump became obvious after 18 months. The MCS community needed a pump that could provide longer-term support. Lastly, the cost of this therapy was quite high, and one or two complications (bleeding or infection) could double or triple the cost. Clearly, if DT were to become a sustainable, widely adopted therapy, patient selection, an improved pump with fewer complications, and a lower cost of therapy would need to occur. A useful algorithm is presented (Fig. 6.1) for patient selection.

Two clinical trials conducted after REMATCH led to a paradigm shift away from volume displacement pumps such as the HeartMate XVE. Both of these trials established continuous

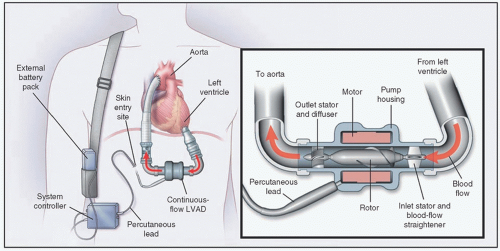

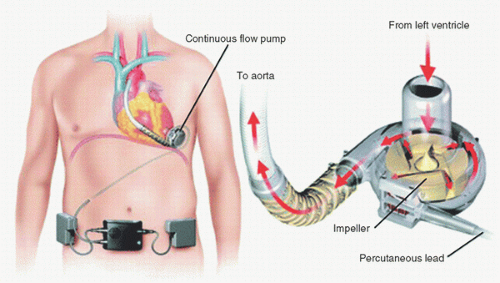

flow as the dominant form of long-term MCS. The first trial was conducted as a multicenter study of 133 patients who were listed for transplantation and subsequently underwent placement of a continuous-flow pump (3). The pump used in this study was the HeartMate II. This axial flow pump (Fig. 6.2) represented a much different pump than any of the volume pumps studied to date. The HeartMate II is smaller than the XVE. Most noteworthy is that there is only one moving part—a rotor—in the HeartMate II. Thus, the mechanical reliability is far superior to the HeartMate XVE. Lastly, the HeartMate II has no valves; thus, another potential mode of failure of the XVE is eliminated. The survival at 6 months was 75% and 68% at 1 year. Both functional status (NYHA Class) and quality of life (Minnesota Living with Heart Failure and Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire) were improved. Patients require anticoagulation with warfarin (target INR 2.0-3.0) and aspirin with this pump. Based on the data in this clinical trial, the HeartMate II was approved as a bridge-to-transplant (BTT) device in early 2008.

flow as the dominant form of long-term MCS. The first trial was conducted as a multicenter study of 133 patients who were listed for transplantation and subsequently underwent placement of a continuous-flow pump (3). The pump used in this study was the HeartMate II. This axial flow pump (Fig. 6.2) represented a much different pump than any of the volume pumps studied to date. The HeartMate II is smaller than the XVE. Most noteworthy is that there is only one moving part—a rotor—in the HeartMate II. Thus, the mechanical reliability is far superior to the HeartMate XVE. Lastly, the HeartMate II has no valves; thus, another potential mode of failure of the XVE is eliminated. The survival at 6 months was 75% and 68% at 1 year. Both functional status (NYHA Class) and quality of life (Minnesota Living with Heart Failure and Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire) were improved. Patients require anticoagulation with warfarin (target INR 2.0-3.0) and aspirin with this pump. Based on the data in this clinical trial, the HeartMate II was approved as a bridge-to-transplant (BTT) device in early 2008.

FIGURE 6.1. Algorithm for selection of LVAD candidates. (Reused from Miller LW, Guglin M. Patient Selection for ventricular assist devices. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;61:1209-1221, with permission.) |

The subsequent clinical trial with the HeartMate II pump enrolled 200 patients who were ineligible for transplantation in a randomized clinical trial (4). The randomization was a 2:1 format, such that 134 patients received the HeartMate II and 66 received the HeartMate XVE. The primary end point assessed was a composite end point of survival at 2 years, free of disabling stroke or pump replacement. The HeartMate II vastly demonstrated superior survival—58% at 2 years versus 24% for the HeartMate XVE. Several interesting facets emerged from these data. Firstly, the survival in the HeartMate XVE group was identical to that in the original REMATCH trial—24% in both groups. This finding confirmed the inability of the HeartMate XVE to provide a long-term MCS platform. Secondly, survival in the HeartMate II group approached 66% in the latter part of the trial, indicating that the technology with continuous flow was a viable platform for long-term survival for patients ineligible for transplantation. This trial also tracked quality of life outcomes, and these outcomes were superior in the HeartMate II continuous-flow group. Based on these data, the FDA approved the HeartMate II pump for DT.

A subsequent analysis of the HeartMate II BTT cohort of 281 patients further extended and confirmed the outstanding outcomes with this pump (5). This analysis included 281 patients of 336 who were treated under the continuous access protocol in the multicenter trial, which examined outcomes in patients listed for transplant who received a HeartMate II pump. The reason that only 281 patients were analyzed is because these 281 had either met study end points or met an 18-month follow-up end point. Survival at 18 months had now increased to 72%. In brief, these data offered a completely new horizon for MCS. In less than a decade, survival increased from 25% to over 70% with the HeartMate II pump at a 2-year end point.

PUMPS CURRENTLY UNDER EVALUATION FOR DT

While the HeartMate II offers many advantages over its predecessor pump, the introduction of a third-generation centrifugal pump the HeartWare ventricular assist device (HVAD) offers a different platform for long-term MCS. The HVAD shares similarity with the HeartMate II as a continuous-flow LVAD. However,

the HVAD is also quite different in that it has no bearing—the pump is suspended in the bloodstream by principally a hydrodynamic force. Further, the HVAD is implanted with an intrapericardial location—no pocket is required for this pump (Fig. 6.3). The HVAD also has a driveline that is tunneled subcutaneously. Two batteries provide several hours of energy for this pump.

the HVAD is also quite different in that it has no bearing—the pump is suspended in the bloodstream by principally a hydrodynamic force. Further, the HVAD is implanted with an intrapericardial location—no pocket is required for this pump (Fig. 6.3). The HVAD also has a driveline that is tunneled subcutaneously. Two batteries provide several hours of energy for this pump.

Currently, the HVAD is FDA approved for BTT only. The multicenter investigational study which evaluated this pump for BTT included 140 patients who received the HVAD pump (6). The control or comparison group was 499 patients who contemporaneously received the HeartMate II pump and had data reported to INTERMACS. The primary end point was

defined as survival on the originally implanted pump, transplantation, or recovery at 180 days. Impressively, “success” as defined by the primary end point for the HVAD was 90.7% and for the control HeartMate II pump was 90.1%. A variety of secondary quality of life outcomes and functional capacity for the HVAD also were met. Based on these data, the FDA granted approval for the HVAD pump as a BTT in 2012. The HVAD is currently undergoing clinical evaluation for a DT indication with the endurance trial.

defined as survival on the originally implanted pump, transplantation, or recovery at 180 days. Impressively, “success” as defined by the primary end point for the HVAD was 90.7% and for the control HeartMate II pump was 90.1%. A variety of secondary quality of life outcomes and functional capacity for the HVAD also were met. Based on these data, the FDA granted approval for the HVAD pump as a BTT in 2012. The HVAD is currently undergoing clinical evaluation for a DT indication with the endurance trial.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree