Lobectomy: Open

Awad El-Ashry

Robert J. Cerfolio

DEFINITION

Anatomic resection of one or more of the pulmonary lobes with ligation and resection of their respective bronchus, arterial supply, and venous drainage (FIG 1).

Indications

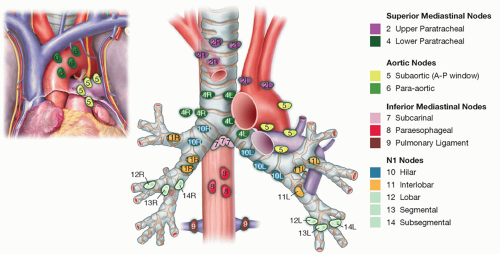

Appropriately staged and selected patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). For the purposes of this chapter, we will focus on oncologic resection of pulmonary lobe together with lymph node (LN) dissection (FIG 2).

Destroyed lobe from chronic infections such as aspergillosis or tuberculosis (TB)

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Growing nodules in a smoker

Chronic cough and/or hemoptysis

Dyspnea

Age older than 50 years

History of smoking

Family or personal history of cancer

Lymphadenopathy

Horner’s syndrome

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Chest x-ray: Plain films may show a pulmonary nodule and are also useful to evaluate for chronic lung conditions such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Historically, the pattern of calcification of the nodule has been used to differentiate between benign and malignant lesions. However, this is not sensitive, as up to 20% of malignant nodules had benign appearance. Serial x-rays may be required to follow the lesion.

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan: A solitary pulmonary nodule is most likely benign; however, high index of suspicion should prompt further investigation to rule out the possibility of malignancy. Typically, malignant nodules enhance more than 20 Hounsfield units (HU), whereas benign nodules are usually less than 15. CT is useful to identify the location (central vs. peripheral), size, characteristics, single versus multiple, presence or absence of direct

extension to mediastinal structures and/or chest wall, and presence or absence of suspicious LNs and their location.

Positron emission tomography (PET) scan: The PET scan is less sensitive, however, more specific than CT in identifying malignant lesions. A lesion with standard uptake value (SUV) of 4.6 is associated with 96% likelihood of malignancy. An uptake of 0 to 2.5 is associated with 25% likelihood of malignancy. For staging purposes, PET scan helps identify the presence or absence of PET avid lymphatic and/or systemic metastasis.

Mediastinoscopy for LN biopsy and staging

Endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS) for LN status and biopsy of suspicious LNs

Navigational bronchoscopy

Pulmonary function test: with focus on forced expiratory volume (FEV1) and diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO). These measures help predict the postresection pulmonary function.

Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) biopsy if the diagnosis is still in doubt

Brain and/or spine CT or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) should be considered to identify possible metastasis, especially if the patient has neurologic symptoms. It was found that up to 18% of NSCLC has brain metastasis at presentation, with 10% asymptomatic.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT—PULMONARY LOBECTOMY

Positioning and Preoperative Planning

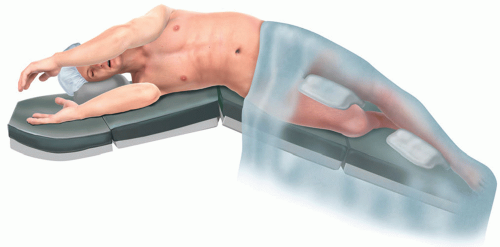

Position the patient supine.

Intubate with a double lumen endotracheal tube.

Perform complete bronchoscopy and confirm position of the double lumen tube for single-lung ventilation.

Place a Foley catheter.

After intubation, place the patient in full lateral decubitus position, the operated side exposed.

Arms in swimmer’s position to display the axilla

Shoulder higher than hip

Legs are positioned with the bottom leg bent and pillow in between to stabilize patient’s lateral position.

Break table (kidney bend/flex) and use additional reverse Trendlenburg to position the patient’s lateral chest wall almost parallel to the floor and the legs are angled toward the floor.

Pad pressure points and bony prominences; appropriately secure body position.

A body warmer to prevent patient hypothermia can be applied.

Curvilinear posterolateral incision at the 5th intercostal space is made starting midway between the medial edge of scapula and spine ending at the anterior axillary line, passing at a point two fingerbreadths below the scapular tip.

We spare the rib as well as the serratus anterior muscle during dissection.

Inject local anesthetic directly into the 5th and 6th intercostals nerve roots.

Apply rib spreader retractor with gradual retraction.

First inspect the pleural space and explore to ensure there are no metastatic lesions on the diaphragm or the parietal or visceral pleura.

The hilum is identified after the lung is retracted posteriorly and inferiorly. The dissection is carried down between the hilar structures and the phrenic nerve.

Sweep phrenic nerve gently down to remove the station 10R LN, avoiding the small phrenic vein that goes to the large station 10R LN that is routinely found in this area.

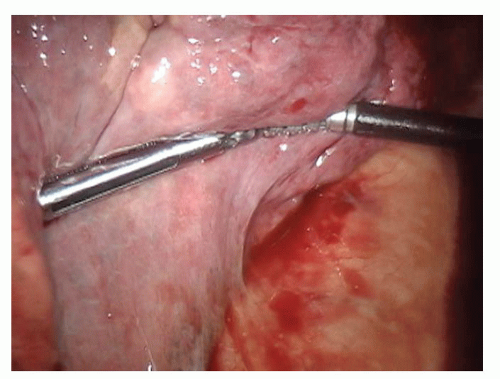

Divide the inferior pulmonary ligament up to the level of the inferior pulmonary vein (IPV). Resect the LNs encountered in this area (stations 8 and 9) and clean the esophagus and vagus nerve of hilar tissue (FIG 3).

NOTE: It is important to place the patients flank exactly over the breaking point (flex or kidney break) of the table. We use the break table/flex function to maximize rib separation.

RIGHT UPPER LOBECTOMY

Develop the bifurcation between middle and upper lobe veins by bluntly dissecting it off of the underlying pulmonary artery (PA) (FIG 4).

Continue en bloc dissection of the hilar tissue to clearly expose the main PA.

Encircle the superior pulmonary vein with a vessel loop and retract it off the PA behind it. Using the vessel loop as a guide, the linear stapling device is passed across the right superior pulmonary vein and fired (FIG 5A-C).

Next, the anterior-apical trunk PA branch is encircled with a vessel loop and transected with a linear stapler in the same fashion as the vein (FIG 6).

The right upper lobe (RUL) bronchus’ anatomy is exposed. Its upper aspect is easily seen coming off the trachea. The dissection is continued inferiorly to expose the inferior edge of the RUL bronchus and free it from the bronchus intermedius (FIG 7).

LN dissection (stations 10R and 11R, hilar and interlobar) is continued along the right main bronchus and the bifurcation between the bronchus intermedius with the upper lobe bronchus identified (FIG 8).

Encircle the RUL bronchus with a vessel loop and transect with a linear stapler. Care must be taken to apply only minimal retraction on the specimen to avoid tearing of PA branches (FIG 9).

Next, the posterior segment of the PA is exposed. The surrounding N1 nodes can be removed and the posterior artery can be encircled with a vessel loop and taken with a vascular stapler (FIG 10).

Prior to stapling the fissure, the anterior aspect of the PA is carefully inspected to ensure there are no PA branches remaining. If so, these are usually quite small and can be easily torn and must be carefully ligated.

The fissure between the RUL and the right middle lobe (RML) is now taken with a stapler (FIG 11). This is usually taken from anterior to posterior; however, it can also be taken from the back.

As division of the fissure is completed, the main PA should be seen and the stapler should be placed just above it after ensuring that all small PA branches to the RUL have been taken. The RML PA branch can be easily seen and should be preserved, and the RUL must be lifted to ensure the bronchus is included in the resected specimen.

To delineate the minor fissure, the upper lobe is retracted superiorly and the middle and lower lobe are pushed inferiorly (FIG 12).

The minor fissure is divided with a linear stapler (FIG 13).

The remaining LN dissection of stations 2R and 4R should be performed (FIG 14).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree