(1)

Department of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery, Papworth Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, Cambridge, UK

Abstract

The need to draw is deeply rooted in our psyche. The intellectual energy of the mind finds a profoundly important release for human creativity and expression in drawing. The commitment of ideas and mental images to paper is a transition from a wholly personal experience to a form of external self-examination and visual communication. Henri Matisse wrote, “I have always seen drawing not as the exercise of a particular skill, but above all as a means of expression of ultimate feelings and states of mind.”

I am really drunk with intellectual vision whenever I take a pencil or engraver into my hand.

William Blake

The need to draw is deeply rooted in our psyche. The intellectual energy of the mind finds a profoundly important release for human creativity and expression in drawing. The commitment of ideas and mental images to paper is a transition from a wholly personal experience to a form of external self-examination and visual communication. Henri Matisse wrote, “I have always seen drawing not as the exercise of a particular skill, but above all as a means of expression of ultimate feelings and states of mind.”1

The act of visualizing our thoughts on paper or other media has both constructive and therapeutic elements. It is a pathway of intellectual and emotional expression, which encourages a refinement of ideas. Yet there is often a dissonance between what we see in “the mind’s eye” and that which our hand reveals, not always as a result of our drawing and writing deficiencies. We commonly find ourselves frustrated by the manual revelations of our grand thoughts and imaginings. If we have tenacity and determination, the process of refinement of image or sentence begins to define us in a way that is identifiable to outside observers. We develop a “style,” which is self-defining. Girolamo Savonarola, the Catholic fanatic and direct contemporary of Leonardo, captured the inescapable truth of this: “Every painter paints himself…. Of course he isn’t doing a self-portrait when he is making pictures of lions or horses, or of [other] men and women, yet even so he is painting himself because he is a painter and expresses what is in his mind. However varied his subject, his work bears the stamp of what he is thinking.”2

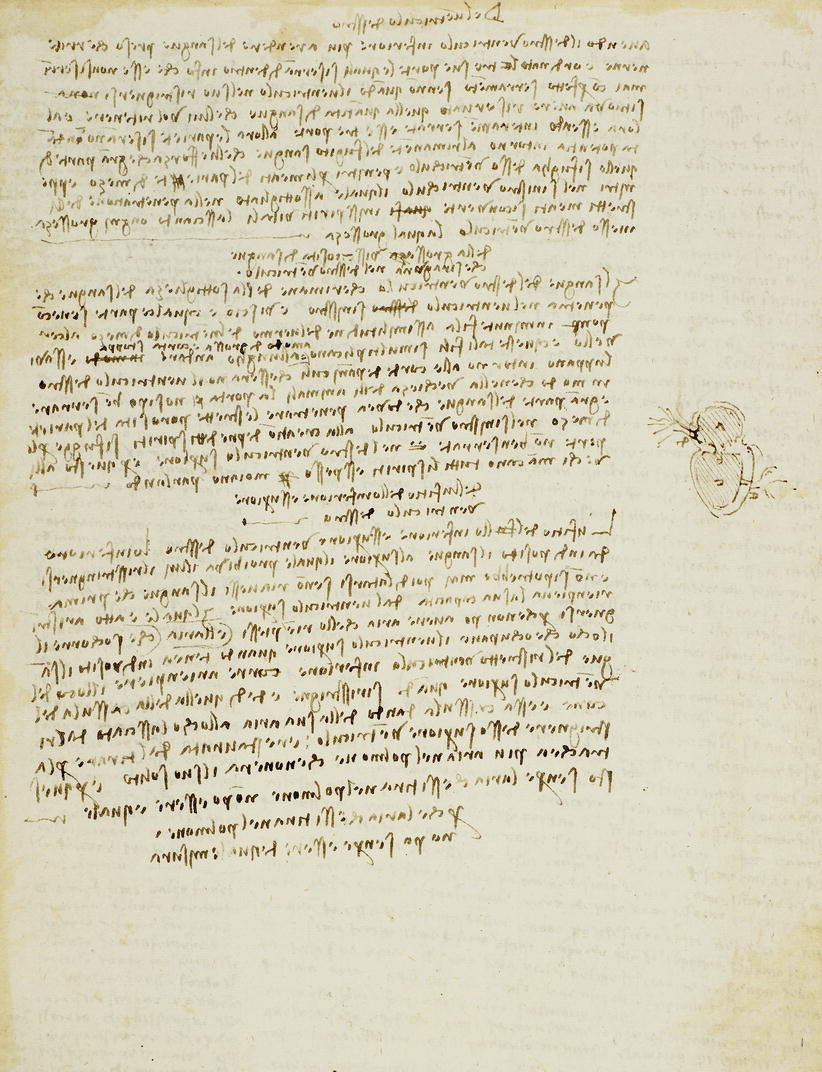

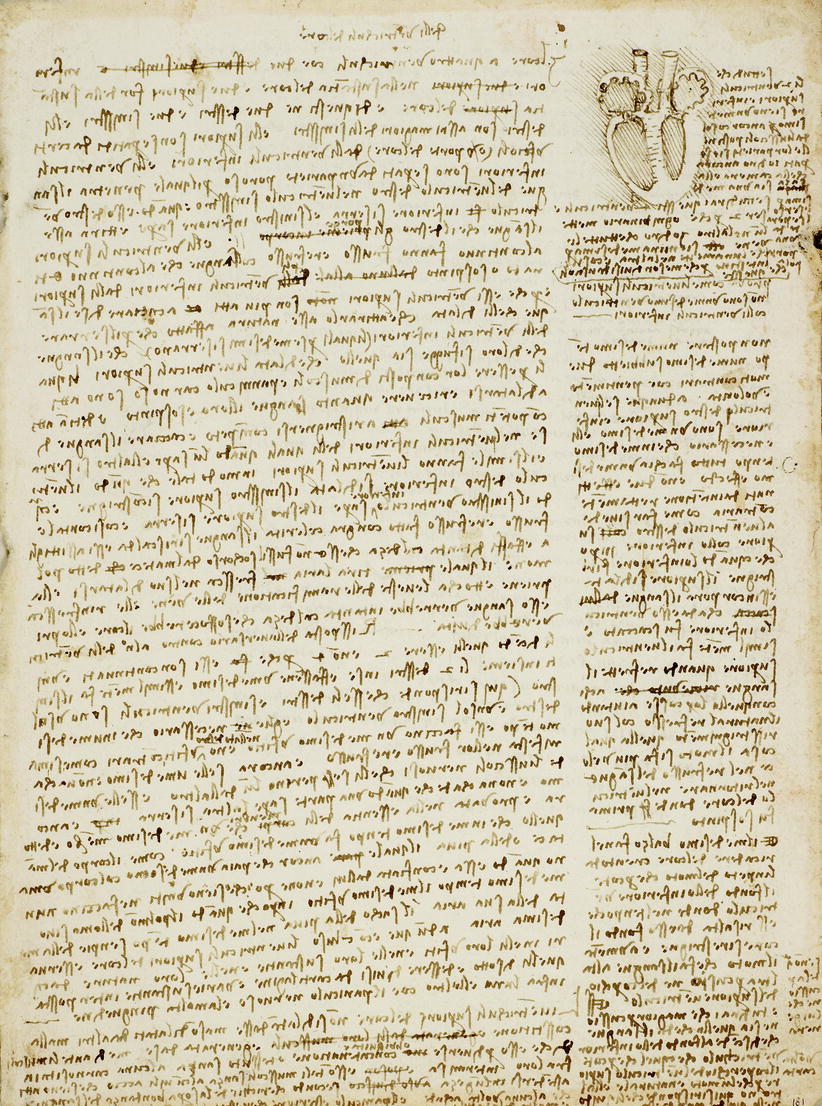

Leonardo repeatedly argued that words alone lack the power to convey a clear notion of visible things, but he was also quick to point out how words are superior in conveying the meaning of things of a philosophical and verbal nature. Bernard Berenson was an American art historian who was active in the first half of the twentieth century, the end of the age of connoisseurship. He wrote extensively on the Italian Renaissance and was gifted with a genius for literary description with an extraordinary distillation of words. He described Leonardo’s notebook content and style in the following way:

In his capacity as a draughtsman his activity was prodigious precisely because he was of all artists the farthest removed from being “merely the artist.” The simple painter or sculptor makes his sketches, as many as you will, for a work that he has in hand, and then like the rest of us, returns to words. But Leonardo’s mind was a universe of which painting and sculpture were scarcely more than outlying continents. His chief interest lay in every form of mechanical and physical science at which a mortal of his day could possibly grasp; and the results of his investigations had to be expressed in words. Now Leonardo, when writing connectedly, was a master of a prose, supple, dignified, even elevated; the prose, in short, of a man of supereminent genius. Nevertheless…he did not believe greatly that words could give a clear notion of visible things. Consequently he rarely wrote without at the same time sketching.”3

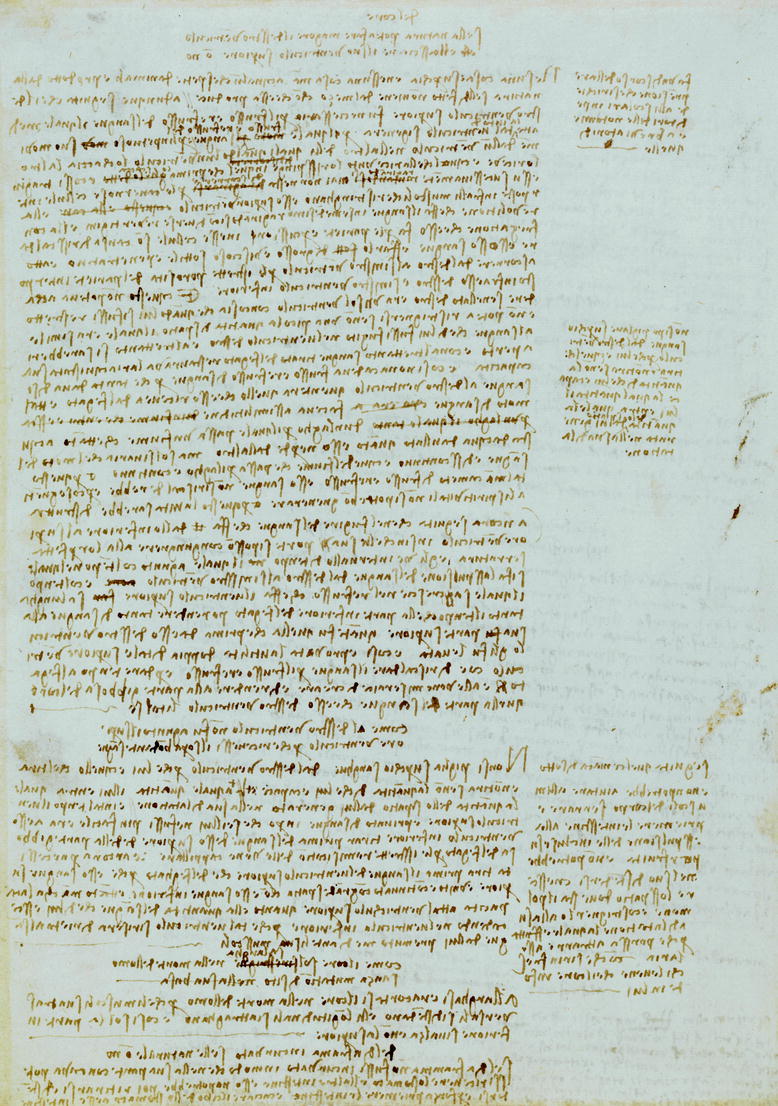

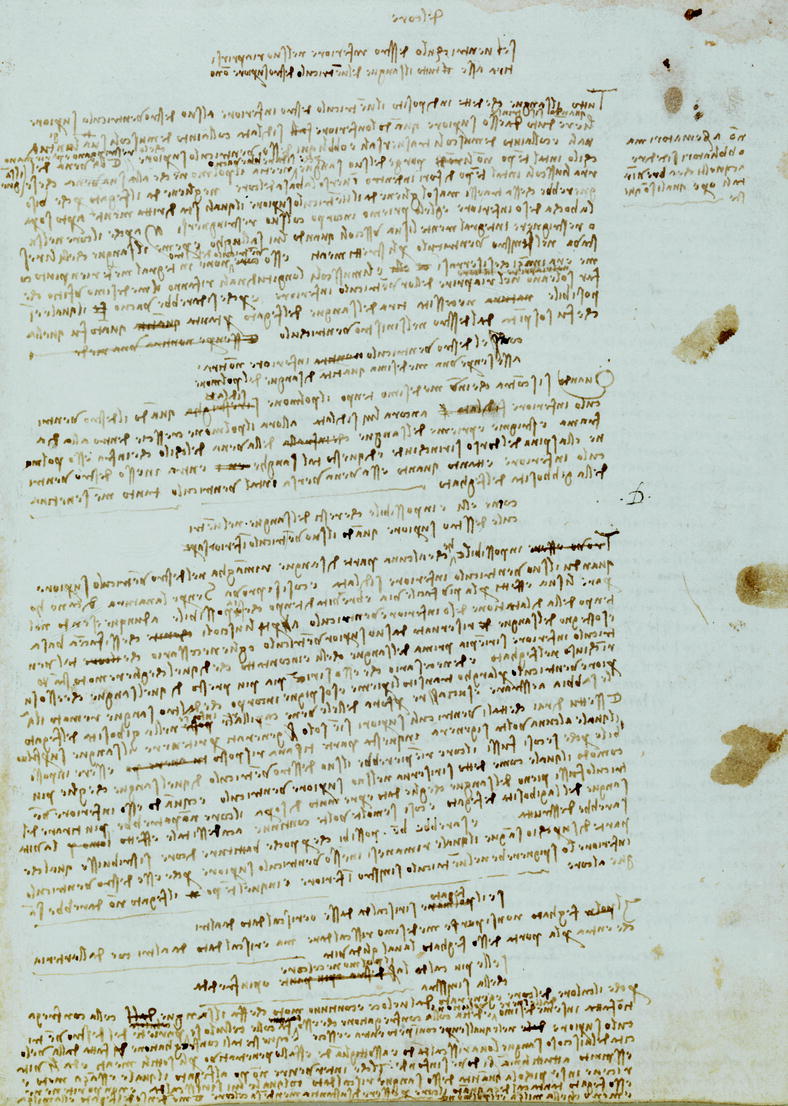

Close scrutiny of the labyrinth of words and images that Leonardo created in his notebooks allows the student a quite exceptionally intimate exchange with their author. Berenson considered that Leonardo’s drawing style and execution was subordinate to purpose. They were not meant for aestheticism but for Leonardo’s eyes alone, recording the development of his thoughts and observations. When we study his pages of notes, we are sharing with him his transference of thought to paper like no other artist/scientist before or since. Quoting Berenson again, “The quality of qualities, then, in Leonardo’s drawing is the feeling it gives of unimpeded, untroubled, unaltered transfer of the object in his vision to the paper, thence to our eye; while, at the same time, this vision of his has such powers of penetrating, interpreting, even of transfiguring the actual, that no matter how commonplace and indifferent his subject-matter would seem to ourselves, his penetration of it is fascinating and even enchanting….”4 His spontaneity, precision, readiness, and intimacy of line characterize his work and mature with his age. Thus, in Berenson’s words, “…none of his sketches exhibits these qualities better than his late studies of human anatomy”.5

In this section, I hope to develop these themes in particular relationship to the cardiac studies of Leonardo, which in my view are the apotheosis of his scientific endeavors and are recorded in a style that is the culmination of years of thoughtful recording.

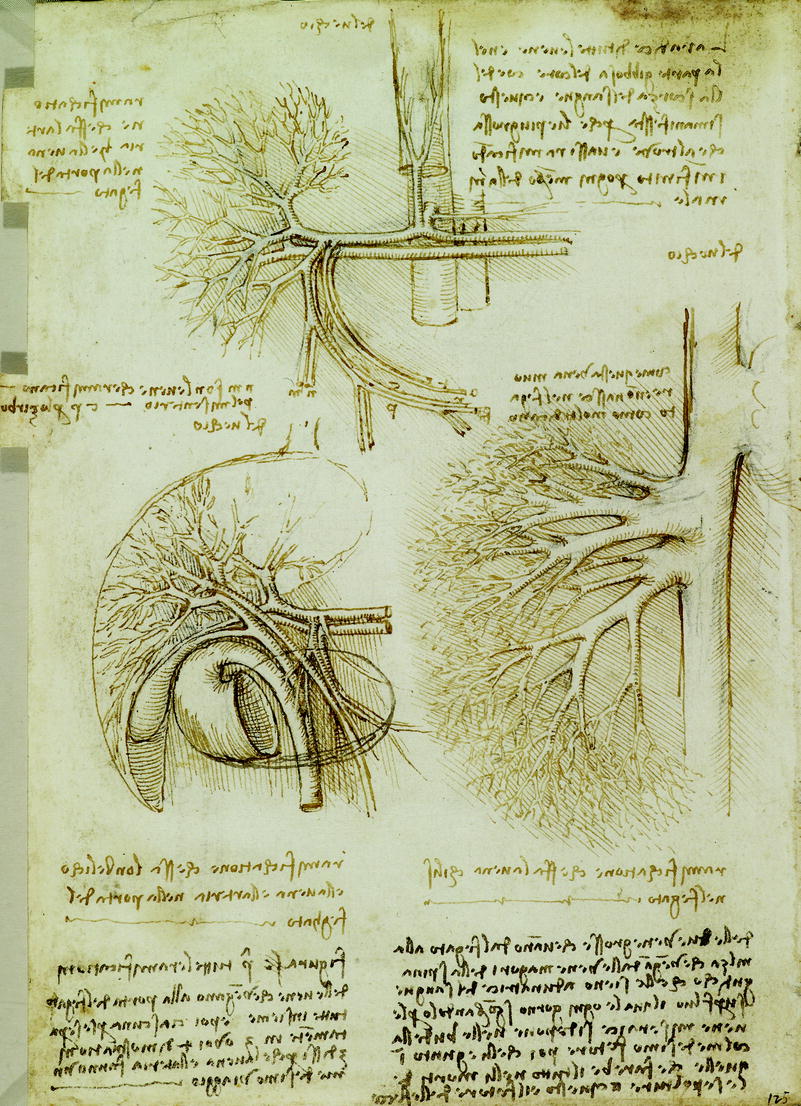

My interest in his heart anatomy caused me to carry out a series of dissections on the heart of an ox. These dissections and the knowledge that I have gained from intimate daily personal experience of the human heart have led me to believe that many of the sheets of Leonardo’s notes are visual and literal dissection notes, made at the time of the dissection or soon after.

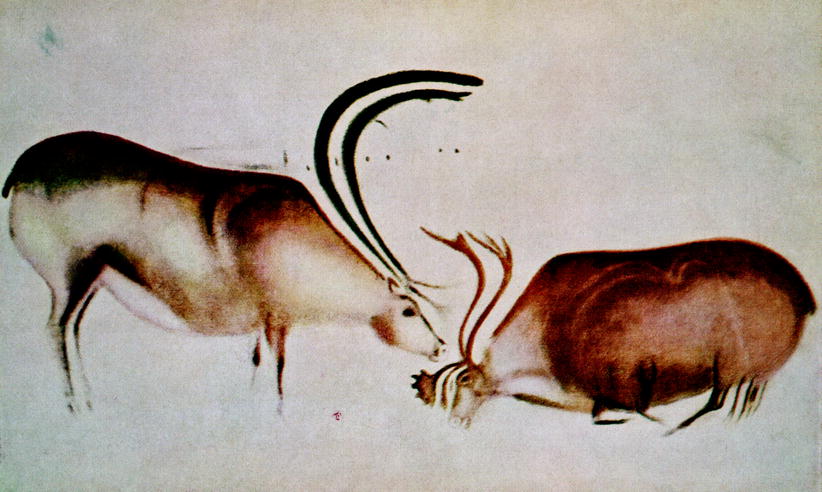

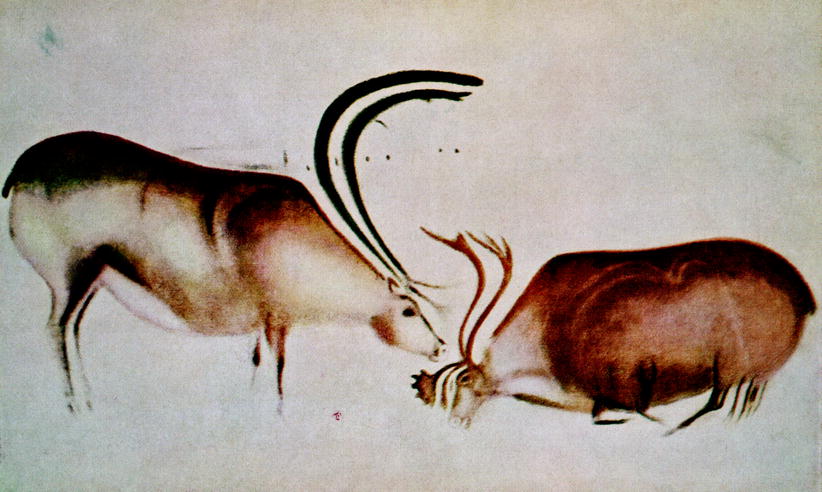

Our desire to communicate emotionally and intellectually is an original and profound part of the way that we are constituted. Man’s earliest known forms of communication involve the figurative use of line. From the French caves of Lascaux and Pindral in northern Spain, to the Egyptian hieroglyph, the means of nonverbal communication was drawing, rather than writing as we would think of it today (Fig. 3.1). It is a natural extension of the visualization of emotions, thoughts, and ideas therefore for them to be recorded by hand in a variety of media as drawings of one form or another. Anthony Gormley wrote of drawing, “For me drawing is a form of thinking. But it is also about medium: using the intrinsic qualities of substances and liquids: a kind of oracular (mysterious or ambiguous) process that requires tuning in to the behaviour of substances as much as to the behaviour of the unconscious, like reading images in tea leaves, trying to make a map of a path of feeling, a trajectory of thought.”6

Fig. 3.1

Cave painting. BAL 3703, Male and female deer, Magdalenian school, c.13000 B.C. (cave painting), Paleolithic/Font de Gaume, France/The Bridgeman Art Library

This theme of a “trajectory of thought” was explored in some depth by the artist Joseph Beuys in his drawings stimulated by Leonardo’s Madrid Codex. Kemp, in an essay included in the Dia publication of this work, wrote, “Leonardo achieved what Beuys called ‘materialized thought’ through a brainstorm style of rough sketching, in which forms emerge from a maelstrom of lines. The power of invention to which this drawing style gave vent was prized by Leonardo and stood at the very center of his enterprise to remake nature in his art”.7 For Beuys, the use of words as an art form was as natural as the act of drawing. There is an element of this combination in the pages of Leonardo’s notebooks, where words and images blend with each other.

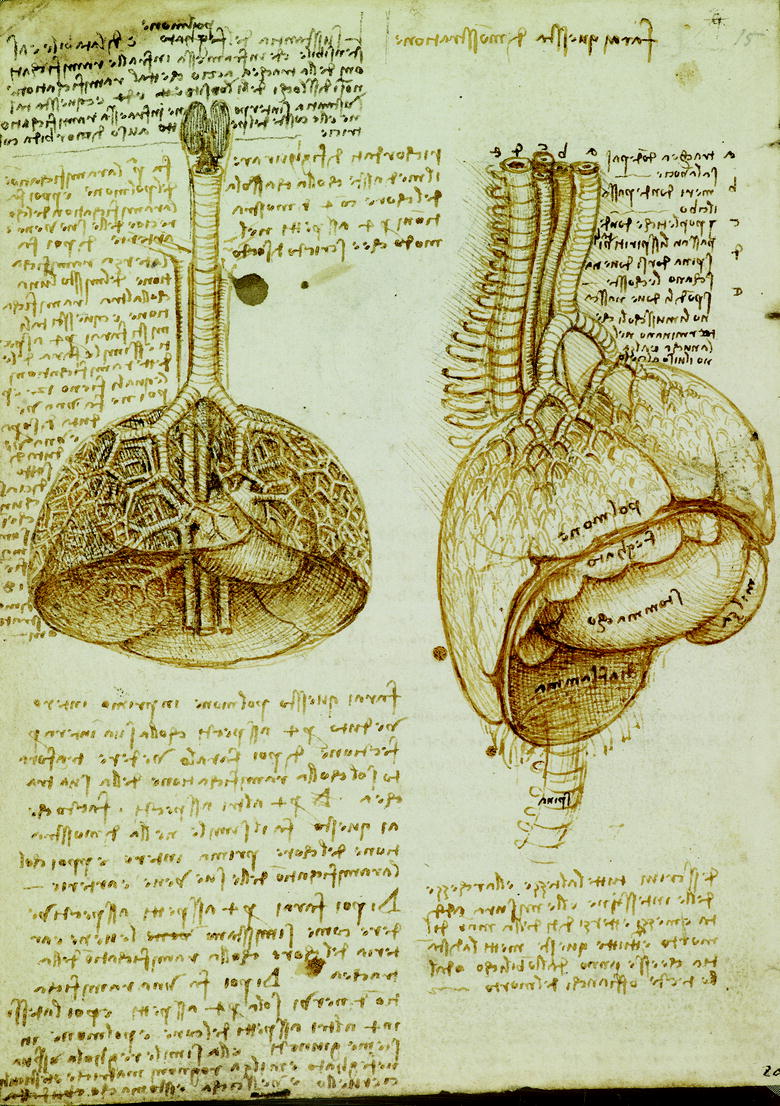

An appreciation of the various uses of drawing in the context of the visualization of thought is important when studying the drawings of Leonardo da Vinci. Here was a draughtsman with divine skills, who produced a line of beauty almost every time his drawing implement touched paper. It is therefore tempting to make the mistake of thinking that each and every drawing by someone who is perhaps known preeminently as an artist is a representation of exactly what he saw. In the context of the anatomical drawings, this is not the case. In this chapter, I hope to demonstrate some of the many ways that drawing may be used as an act of communication, in an attempt to help the observer understand the types of drawings that can be seen within Leonardo’s anatomical notebooks. This is important if one is to attempt to explain some of the criticisms of the accuracy of his work. It is also important to recognize that a considerable proportion of the heart drawings are from the ox; perhaps two, if any, are of human origin. Indeed, one very rough sketch may be taken from a small mammal such as a rabbit or a mouse.8

Drawing is a highly intellectual process and for best effect requires a considerable degree of insight and higher cerebral function. One only has to watch a professional artist at work to realize the enormous amount of thoughtful observation that goes into each stroke of the pen. Several examples of this process have been captured on film. One of the best is of Matisse at work producing the extraordinarily beautiful line drawings that are so well known from the latter part of his career. He can be seen in front of the model, pen in hand, observing intensely for considerable periods before making a finished line.

Anyone who has practiced the art of drawing will know that a deep appreciation of the subject is essential if a line true to the object can be made without several alterations. Careful observation of so many of the anatomical drawings of Leonardo, many of which are only sketches, reveals the accuracy of his use of line. Some of his earlier work is done using silver point, a technique that allows no rubbing out and requires absolute accuracy of line to produce a satisfactory effect. There is no doubt that Leonardo was the master of this medium, as with all others. In other preparatory drawings for artistic projects, there are multiple lines around the finished object, allowing the viewer to see the way his thoughts drew him to the desired finished image. These “pentimenti” are described in more detail later.

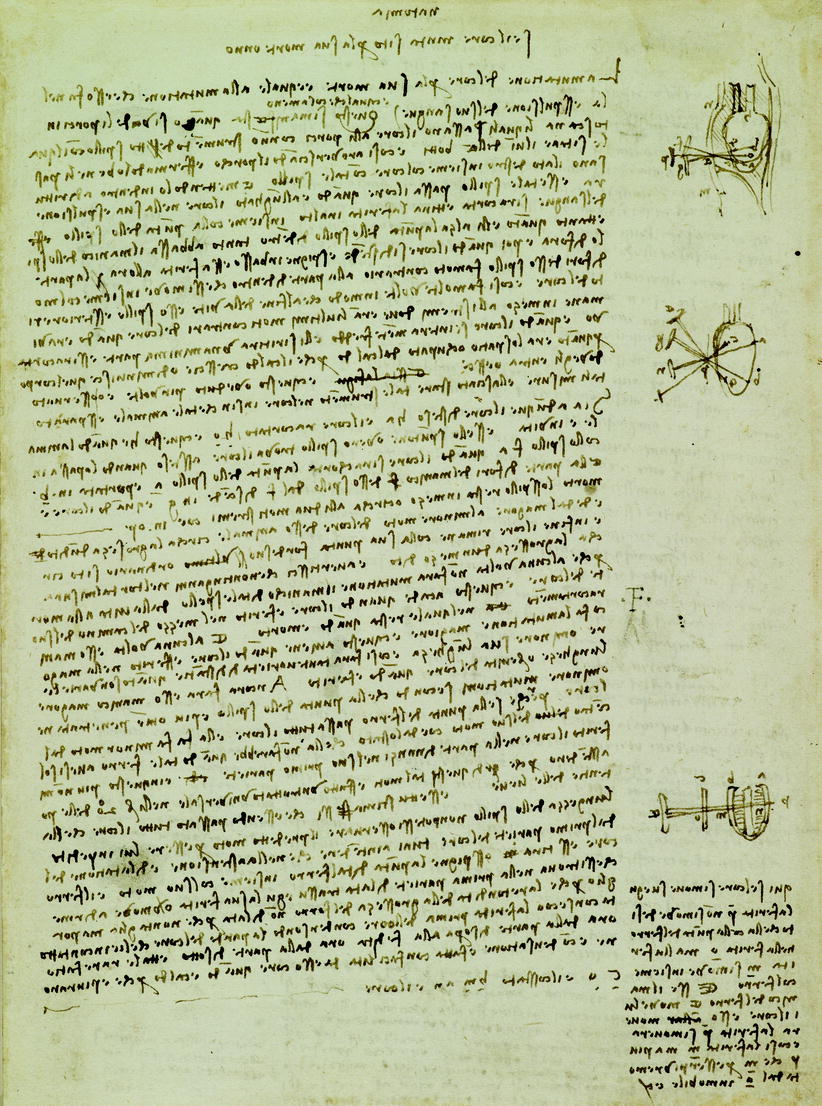

In addition, his mastery of the medium can be witnessed by close examination of the perfect gradation of shading used to clarify very complex forms within the heart. Leonardo’s rendering of the opened right ventricle, as shown in RL 19119 verso, allow an immense clarity of depth perspective that is only realized when studied with a hand lens. Often it is as simple a maneuver as a rotation of the wrist or fingers to change the thickness or weight of the line, as seen in the detail in RL 19117 verso (top right), which shows the individual drawing of the aortic valve opening.

Therefore, in addition to a complete mastery of the form in the mind’s eye, the neuromuscular control of the drawing hand needs much practice to give the correct and touch required to produce the finished line, giving vivacity through variations of thickness and weight. This is the skill honed with hours of practice, which in harmony with natural talent produces the work of the master. In this respect, the process may be likened to the technical skill of the musician, the sportsman, or (dare it be said?) the surgeon, to name but a few examples. The result may be practical or beautiful—or in the case of Leonardo, both practical and beautiful.

Leonardo used a variety of media for his drawing. As already mentioned, some of the earliest anatomical works are in a thin and tentative silverpoint style on blue prepared paper. This exceedingly demanding form of drawing leaves every stroke of the metal tracer bound in the prepared surface of the paper; it cannot be erased or reworked. His study of hands (Fig. 3.2) is one of his most beautiful creations in silverpoint. It is very close in imagery to Verrochio’s terracotta bust, Lady with a Bunch of Flowers, and may be related to work in Verrocchio’s studio.9 Most of the anatomical heart illustrations are in pen and ink with black chalk. Most are done on blue paper, but he seems to have switched to cream paper during his last phase of heart drawings, probably completed in Rome.

Fig. 3.2

Silverpoint heightened with white, on pink prepared paper; probably before 1490. RL 12558, A study of a woman’s hands. Leonardo da Vinci c.1490. Metalpoint with white heightening over charcoal on pale buff prepared paper (Lent by Her Majesty The Queen. Royal Collection © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II)

The definitive archaeology of these drawings remains to be completed and we depend upon the scholarship of Kenneth Clark, Kenneth Keele, Carlo Pedretti, and Martin Kemp for our current knowledge.

The Types of Drawing

Drawing underpins so many of our activities. In almost every walk of life, drawing has an important function. This very natural act extends from such everyday things as communicating travel directions to a friend to the setting down of complex architectural drawings and engineering plans; from the aesthetic beauty of an Old Master drawing to the simple, mindless doodle that we all engage in from time to time. Between these extremes occur a myriad of uses. This part of the chapter reviews with examples some of those used in Leonardo’s anatomical notebooks.

But first consider Leonardo’s invention for generating ideas simply by studying stains on a wall. He explained how painters can find new invenzioni (ideas) from allowing the mind to drift whilst studying stains. He wrote:

Way to augment and stimulate the mind towards various discoveries. I shall not fail to include among these precepts a new discovery, an aid to reflection, which, although it seems a small thing and almost laughable, nevertheless is very useful in stimulating the mind to various ‘invenzionis.’ This is: look at walls splashed with a number of stains or various stones of mixed colours. If you have to invent some scene, you can see the resemblances to a number of landscapes, adorned in various ways with mountains, rivers, rocks, trees, great plains, valleys and hills. Moreover, you can see various battles, and rapid actions of figures, strange expressions on faces, costumes, and an infinite number of things, which you can reduce to good integrated form. This happens thus on walls and varicoloured stones, as in the sound of bells, in those pealing you can find every name and word you can imagine. Do not despise my opinion, when I remind you that it should not be hard for you to stop sometimes and look into stains on walls or the ashes of a fire, or the clouds, or mud, or like things in which if you consider them well you will find marvelous new ideas. The mind of the painter is stimulated to new invenzioni, the composition of battles of animals and men, various compositions of landscapes and monstrous things such as devils and similar creations, which may bring you honour, because the mind is stimulated to new invenzioni by obscure things.

Although others had described this practice before Leonardo, his characterization of these mental perambulations as being positive and creative is new. The first person that is known to have written about it, albeit in a noninventive way, was Aristotle in De Somniis. He wrote “…that we are easily deceived respecting the operation of sense perception when we are excited by the emotions…. This is the reason, too, why persons in the delirium of fever sometimes think that they see animals on their chamber walls, an illusion arising from the faint resemblance to animals of the markings thereon when put together in patterns.”

Leon Battista Alberti, whilst not extolling the process as desirable, wrote of it as an explanation for the imitation of natural things by artists. He wrote, “I believe that the Arts of those who attempt to create images and likenesses from bodies produced by nature, originated in the following way. They probably occasionally observed in a tree-trunk or clod of earth and other similar inanimate objects certain outlines in which with slight alterations, something very similar to the real faces in nature was represented. They began, therefore by diligently observing and studying such things to try to see whether they could not add, take away, or otherwise supply whatever seemed lacking to effect and complete the true likeness.”10 It seems fair then to assume that Leonardo was the first to record his thoughts of this method as a constructive and creative process.

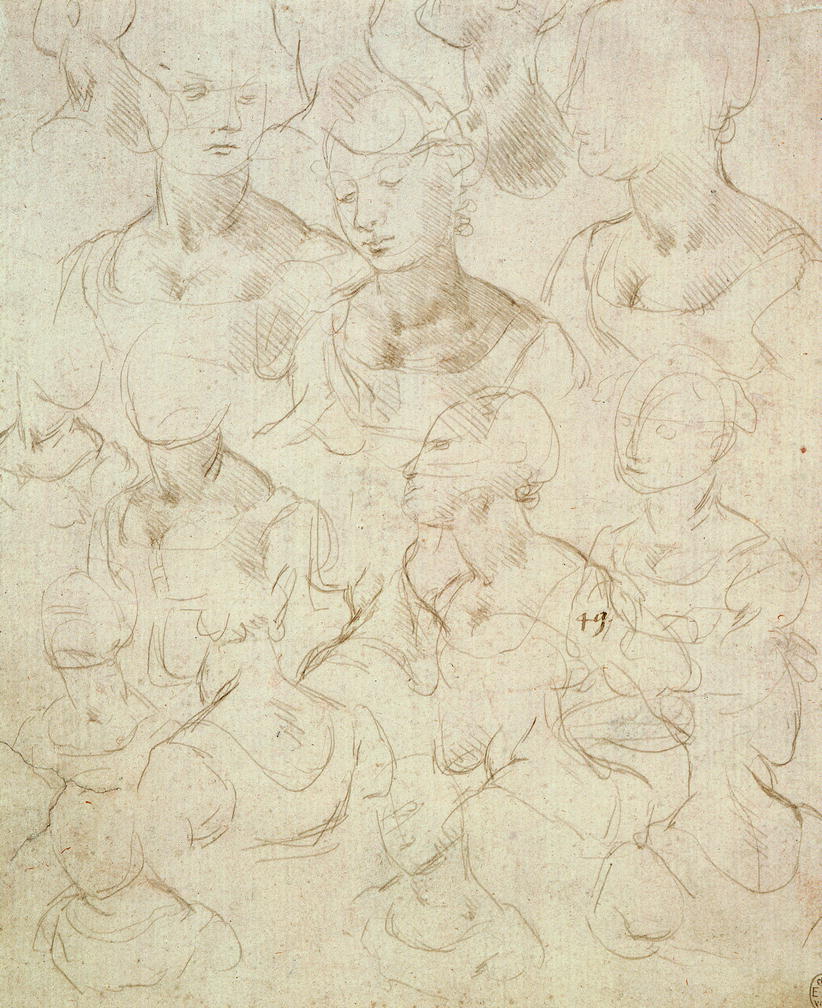

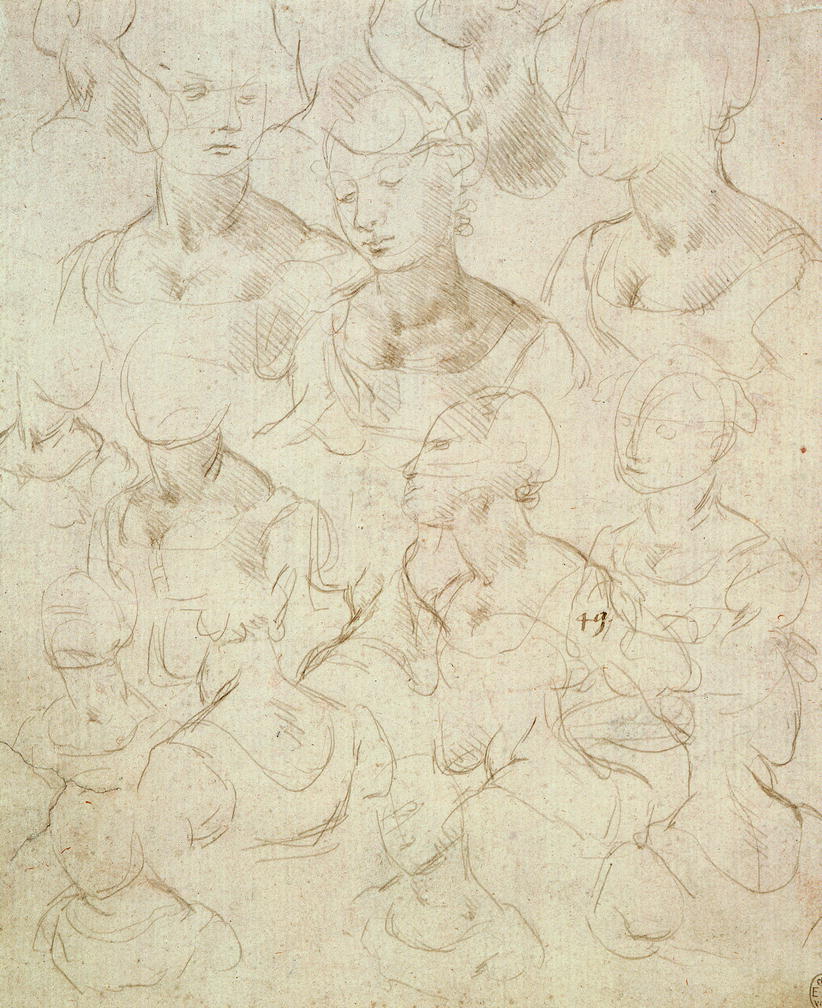

A distinctive aspect of Leonardo’s drawing style is his regular acceptance or even use of allowing inaccurate lines or “mistakes” to remain on the page. This practice is referred to as pentimenti. Instead of erasing imprecise lines, Leonardo left them; the true shape of his creation was to appear within the boundaries of several attempts. This appearance almost gives another life to the drawing, which is lost within the perfection of the perfect line (Fig. 3.3). These pentimenti can be found with infrared spectrographic and x-ray examination of his paintings and is used as a way of establishing the authenticity of a work by Leonardo.

Fig. 3.3

A further example of pentimenti. RL 12513, Sketches of the bust of a woman. Leonardo da Vinci, c.1490. Metalpoint on pale buff prepared paper (Lent by Her Majesty The Queen. Royal Collection © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II)

Interestingly, pentimenti are not really a feature of his anatomical drawings of the heart, suggesting that most of them are quick representations of ideas and that the image that we see is not as important as the record of the thought. The more finished drawings may have been intended to be seen publicly; they were prepared for transfer to copper plate, Leonardo’s preferred method for printing, as it gave a much more refined image. In these drawings, the lines of inquisitive thought have been removed.

To get the most from looking at Leonardo’s anatomical manuscripts, it is important to think about the uses that Leonardo makes of drawn representation. Coming from the hand of Leonardo, perhaps the greatest draughtsman of all time, it is easy to understand that the new observer will expect each and every drawing to be a finished masterpiece. What is found, however, is in some ways more interesting. The observer can see Leonardo’s various uses of drawing. Drawing is visual thinking as well as the representation of truth and beauty. This range of uses is very well summarized in Leonardo’s techniques, which we can group into five categories:

Thinking through drawing

Compilation and summarized memory

Schematic and diagrammatic drawing

Representational drawing

Four-dimensional drawing implying movement

Thinking Through Drawing

Drawing as part of “thought” is something that most of us do at some time, if only to find ourselves “doodling the time away.” As our minds are far away from the moment, we find ourselves producing images partly as aesthetic relaxation and partly as if in a trance. The physical act of drawing is linked to the deeper recesses of our minds. An example of a doodle amongst Leonardo’s cardiac anatomical notes is the drawing of a beautiful young man with curls in his hair, within the outline of whose chest is a drawing of a section of the heart (Fig. 3.4). This profile of the young man is not dissimilar to Verrocchio’s bronze sculpture of David or the outwardly looking young man found at the extreme right side of Leonardo’s unfinished painting of the Adoration of the Magi. Perhaps it is a self-portrait, perhaps it is his wayward helper Salai, or perhaps it is just a fantasy. Is the preexisting drawing of the heart subliminally involved in the fantasy also? (Be still, my beating heart!). It is clear that the chronology of the drawing of the young man is separate from the sectional drawing of the heart enclosed within it. We may make this assumption, as the surface anatomy of the position of the heart is completely wrong for that of the rest of the drawing. Perhaps the doodle was made around the preexisting heart drawing, as it is likely that the drawings were made at different times, perhaps separated by some years.

Fig. 3.4

This drawing of a young man enclosing the drawing of the heart may represent a likeness of Salai, Leonardo’s young servant. Detail from RL 19093 recto. Studies of the heart, and the head of a youth in profile. Leonardo da Vinci, c. 1511–3. Pen and ink on blue paper (Lent by Her Majesty The Queen. Royal Collection © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II)

Other more important drawings illustrating thinking on paper are to be found in his working out of the mechanism of closure of the aortic valve. Here we can see analytical thought in process (See RL 19117 verso). These will be discussed at length in the next section.

Compilation and Summarized Memory

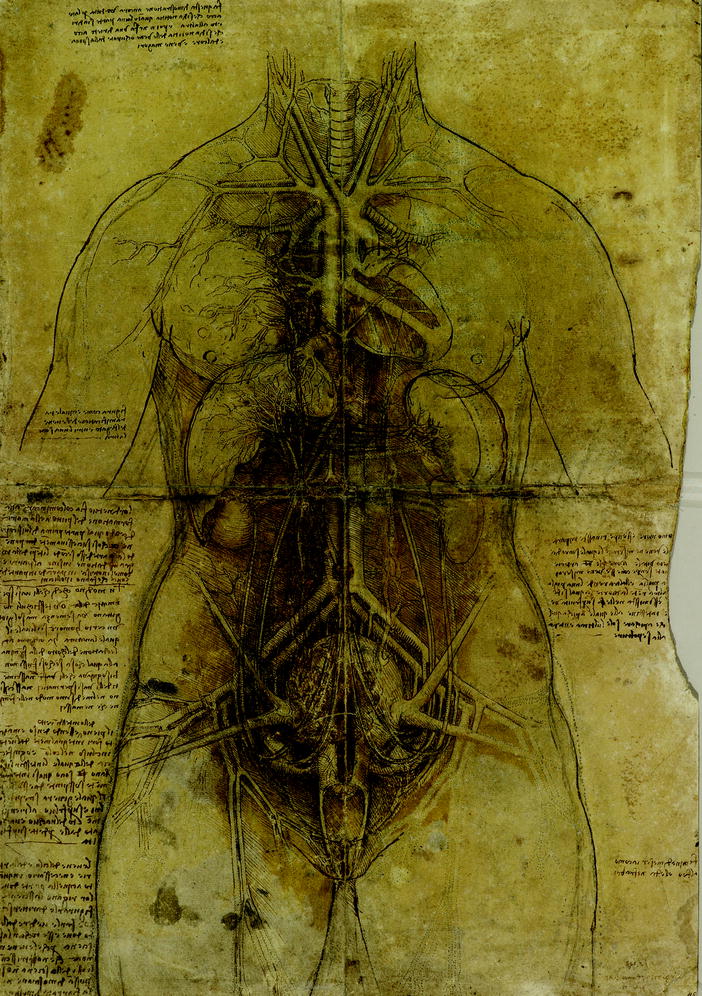

The well-known “Great Lady” (Fig. 2.6) is an example of a compilation drawing. It seems clear to me that this is a summary statement by Leonardo of his anatomical understanding of the interior of the body of a woman. Perhaps it was produced by studying separate drawings that he had made of individual structures and systems, or perhaps it represents his summarized memories in a single drawing. However it was produced, it is interesting in many ways.

This drawing contains several examples of style and substance and is worth dwelling on for a moment. Of significance is the fact that it demonstrates that at some stage of his development as an anatomist, Leonardo was of the common opinion (which is Galenic in influence) that the interior of all animals is similar and that man was no exception. The real fascination for anatomists of the day was the mystery of the uterus and the development of the foetus that was to be found therein.

In this drawing, a mixture of species and ages is represented. The vascular system and uterus are those of an ox. The arrangement of the vessels in the neck and in the abdomen is not human, but belongs to a quadruped. The relationships of the major abdominal organs (liver and spleen), however, are more humanoid. Also, the representational styles of each organ are different: The heart is in cross-section, but the thyroid gland and the liver and lungs are semitranslucent. Finally, the blood vessels swooping from the pelvic vessels (the iliac arteries) around and up to the umbilicus (in this case set off-centre) are those of a foetus.

Whether this drawing was produced from memory or compiled from his previous work we cannot know, but it does raise the interesting point of the integrative power of the brain when reassembling memorized facts in this way. Memory is often used as a test of learning and understanding. The use of spatial thinking in the arrangement of memories gives powerful reinforcement.

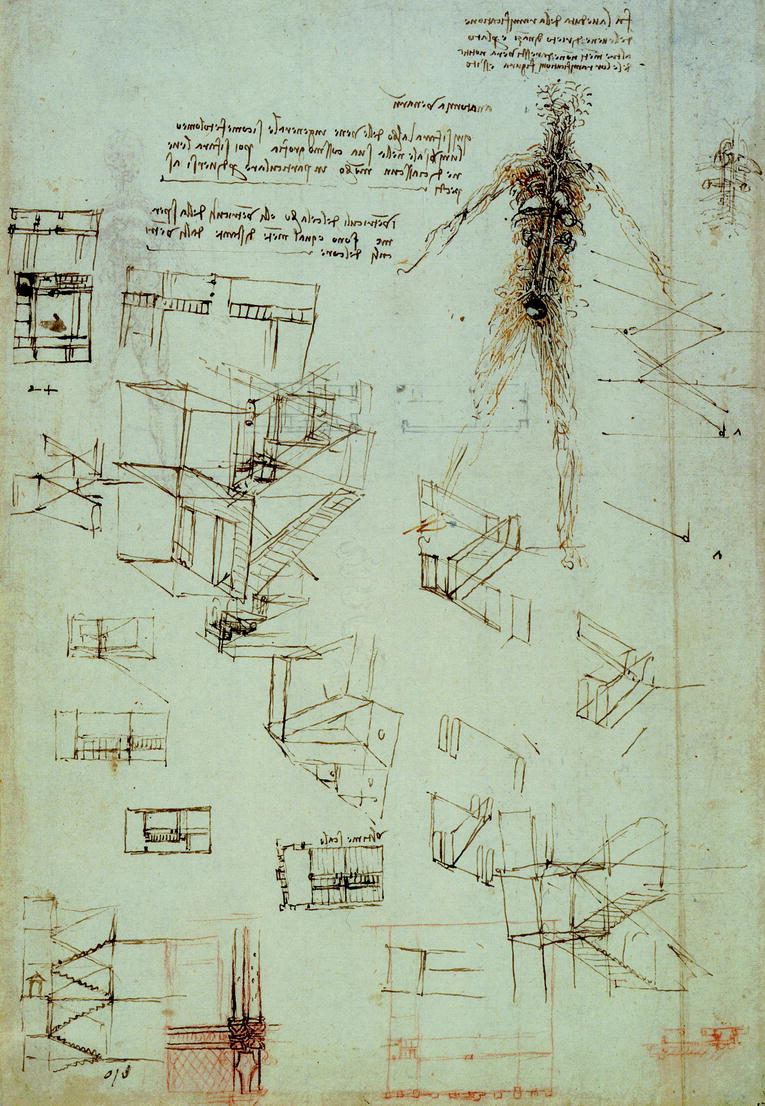

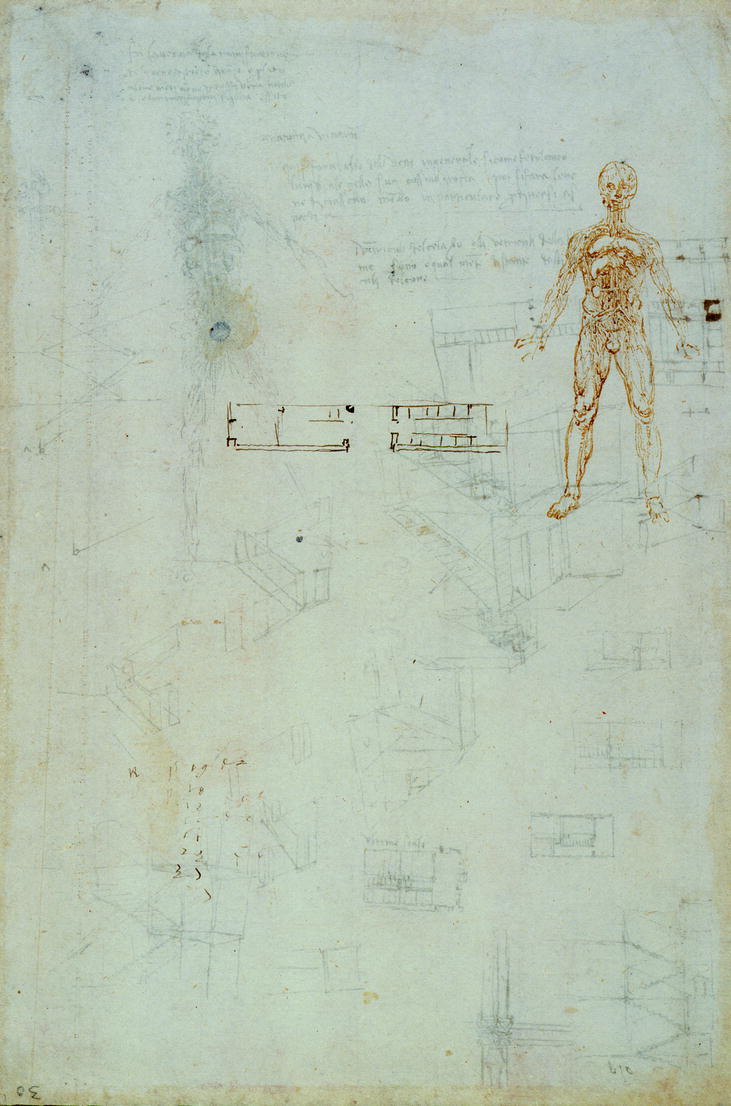

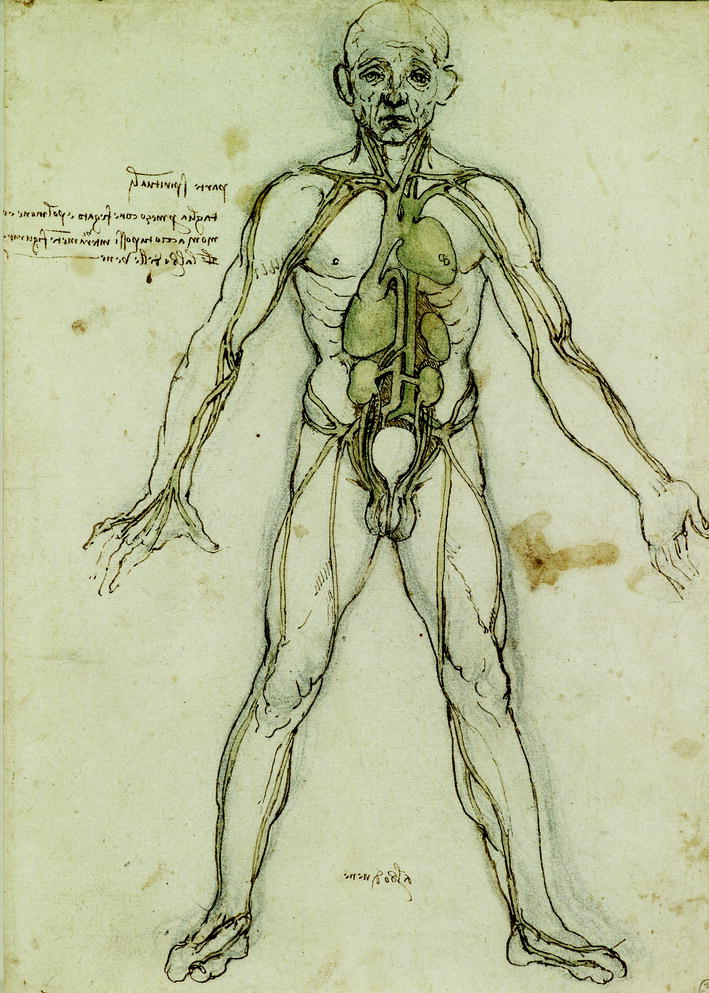

Schematic and Diagrammatic Drawing

Leonardo uses schematic diagrams frequently in this series of work. His very Galenic sketch of the heart and the other major thoracic and abdominal viscera (RL 19112 recto) is clearly a schematic drawing, perhaps from memory. A very similar representation is to be found in his earliest known anatomical illustration of the vascular tree superimposed upon a drawing of a nude man (RL 12597). Also in RL 19074 recto, there is a very faint drawing of a system of pulleys in the centre of the page. This is part of Leonardo’s examination and explanation of the engineering mechanism involved in the opening and closure of the mitral and tricuspid valves. Here he has reduced his anatomical observations into a mechanical drawing that any secondary-school physics student would be familiar with.

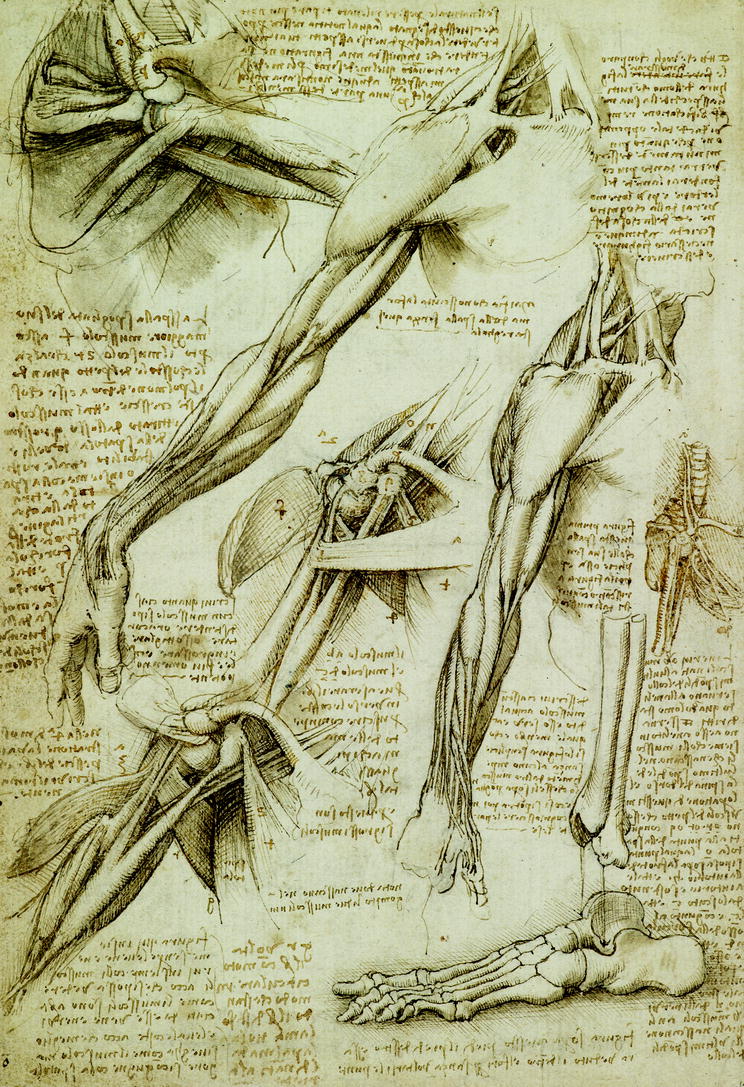

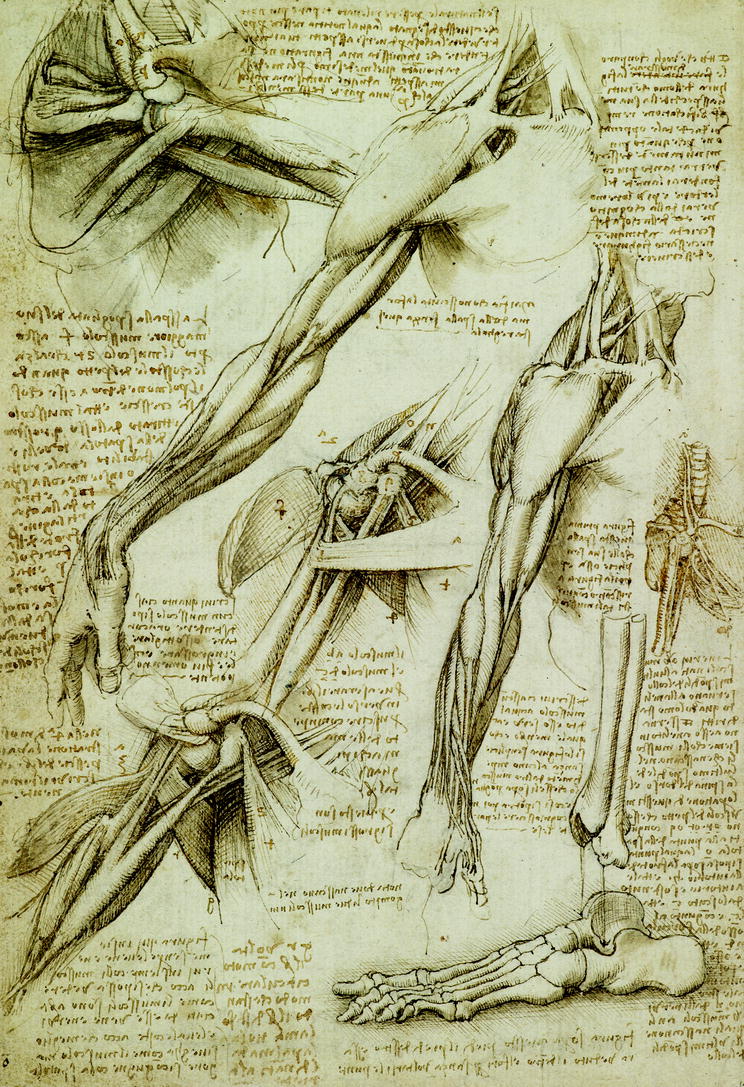

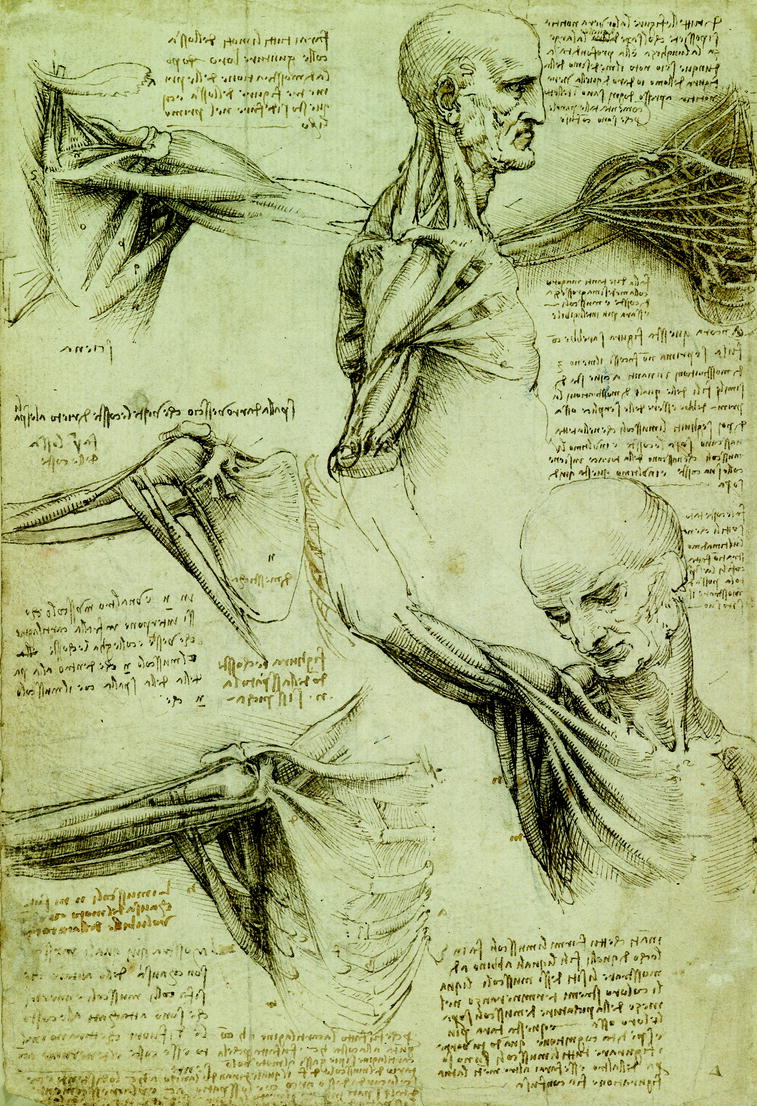

An illustrative tool that Leonardo used to great effect in his anatomy (particularly the musculoskeletal drawings) is the exploded diagram. Today the exploded diagram is commonplace, but it was more unusual in his time. Certainly he and others had used it in architecture and mechanical drawing, but his use of it in anatomy appears to be completely novel. His use of this illusory technique, allowing a fuller examination of the relationship of one part to another, is an example of diagrammatic representation at its best (Fig. 3.5). Perhaps Leonardo learned the technique from a friend, Francesco di Giorgio Martini, who had learned it from his teacher Taccola.

Fig. 3.5

An example of an exploded diagram used so effectively by Leonardo. RL 19013 verso, The muscles of the shoulder and arm, and the bones of the foot. Leonardo da Vinci, c.1510–1. Pen and ink with wash, over black chalk (Lent by Her Majesty The Queen. Royal Collection © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II)

A clue to the possible influence of contemporaries on Leonardo can be gained from the surviving work of Di Giorgio, particularly his Trattato di Architettura, which he probably gave to Leonardo in 1490 in Milan. This volume has survived, and in it can be seen Leonardo’s notes on the sides of the pages. The book was written in 1480, whilst Francesco was at the court of Federico da Montefeltro in Urbino. Francesco is remembered for his stylized ideal city. His designs for fortress battlements and other features are very similar to those found in Leonardo’s notebooks.

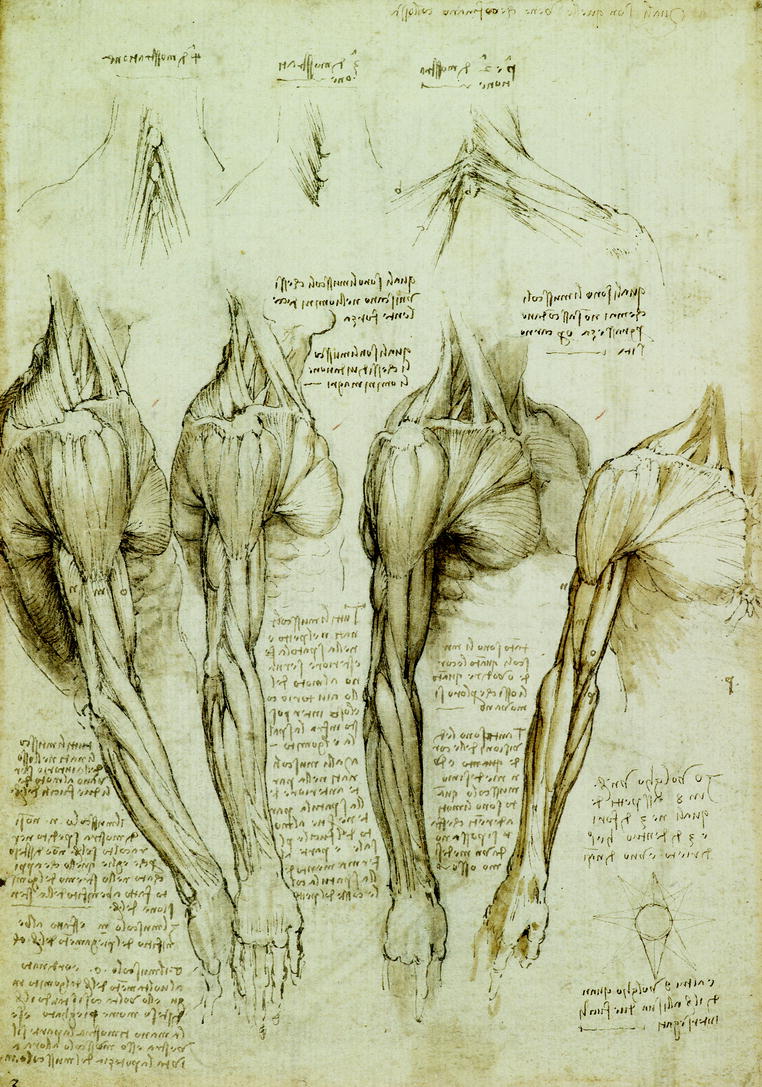

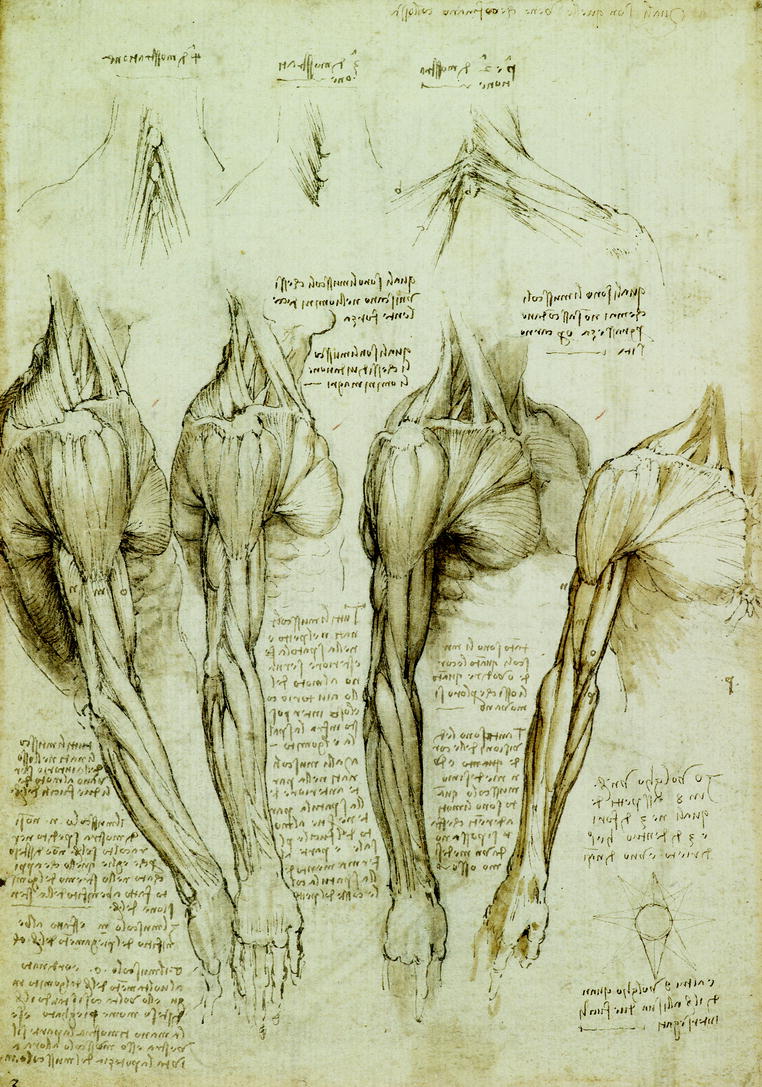

Representational Drawing

Leonardo’s representational drawing is to be found in some of the anatomical drawings that he may have thought were ready for publication. These are to be found particularly in the musculoskeletal work (Fig. 3.6). Here there is a finish not seen in many of the others. They are aesthetically so pleasing that one can understand a reluctance on Leonardo’s part to have their refinement reduced by conversion to woodcut, which was the common mode of transferring illustration in that early time of printing. Just as with every other area of his work, he became engrossed in perfecting the tools for execution of the project as much as in the project itself. An example is the design and building of the scaffolding for both the Last Supper in Milan and the Battle of Anghiari in Florence. The frustration caused by his painfully slow progress was commented upon at the time. The pride that Leonardo had in his prowess as a skilled draughtsman meant that many of his drawings were much more than mere illustrations. One can hear his salutary words echoing in our ears: “And though you have a love for such things, you will perhaps be impeded by your stomach…or perhaps the lack of draughtsmanship which appertains to such representation and even if you have the skill in drawing, it may not be accompanied by a knowledge of perspective or geometry.”.11 Perhaps Leonardo became so preoccupied with trying to find ways of transferring the detail of line in his drawings that it interfered with the possibility of their publication.

Fig. 3.6

Fine examples of (near) finished drawings, perhaps ready for publication. RL 19008 verso, The muscles of the shoulder, arm and neck. Leonardo da Vinci, c.1510–1. Pen and ink with wash over black chalk (Lent by Her Majesty The Queen. Royal Collection © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II)

Four-Dimensional Drawing Implying Movement

Drawing in four dimensions is of course not possible without an artificial construct, such as the flipbooks that we see today mainly as amusements for children. However, if we read Leonardo’s intention to present his anatomy in such a way as “to have the very person in front of the viewer” and we look at the sheets RL 19008 verso (Fig. 3.6) and RL 19005 verso, it is possible to imagine the arm there represented, turning in front of you. This movement through time represents a fourth dimension not remotely available in any other anatomical demonstration until the present time. There is something of this quality in the drawings of the vortex formation in the aortic valve sinuses and the opening and closing of the aortic/pulmonary valves. Hence his demand for many views of the same part of anatomy can be seen almost in a cinematographic sense.

It is clear to me that Leonardo derived amusement from some of his personal adventures on paper. A classic example is the pictogram, of which he completed a number (see RL 12692 recto). This child’s game on paper has been used by generations and continues today. On a page of drawings of the aortic valve, he places two oblique strikes through the letter “Q” in one part of the notes as if mimicking the bileaflet aortic valve on another part of the page.

Leonardo’s work contains a lot of lateral thinking. His architectural experience carries over into his anatomical work. As discussed earlier, the Vitruvian concept is a classic example. Again, an influence here was almost certainly Francesco di Giorgio Martini, as well as Alberti. Leonardo’s use of cross sections and proportion theory also calls heavily upon his architectural practice and experience.

Leonardo’s drawing of the mitral valve of an ox in RL 19080 recto, is reminiscent of the nave of a church. This very organic form can be seen reproduced in the nave of Gaudi’s La Sagrada Familia in Barcelona. Gaudi’s work is very organic, and his approach to the influence of nature on man is similar to that of Leonardo (Fig. 3.7).

Fig. 3.7

The roof buttresses of La Sagrada Familia, Barcelona, designed by Antoni Gaudi. These wonderful organic shapes mirror the underside of the mitral valve

Finally, there are a number of sketches amongst Leonardo’s pages that are not so easy to work out. One amongst them is a small drawing that represents the interaction of the cords with the leaflets of the mitral valve and as such is another example of Leonardo’s thinking on paper. This drawing is found on manuscript RL 19087 recto at the top of the page. With this drawing, Leonardo seems to be imagining the change in position of the chordae tendinae with the opening and closing of the mitral valve. It is likely that the two components of the drawing represent his perception of the position of the supporting cords of the valve in the two phases of the cardiac cycle, systole (the contracting phase) and diastole (the phase of relaxation).

Drawing with the Left Hand

Leonardo’s use of his left hand to write and draw is well known. Much has been made of it, with some suggesting that it was a device to codify his ideas. Whilst he may have done this occasionally, it is much more likely that left-handedness was his natural form. Left-handed people have to hold the pen in an awkward position to be able to draw it across the page from left to right, the natural thing for right-handed people. To write from right to left with the left hand reproduces this ease of movement and works with the nib or quill of the pen. The mirror-image component of his writing can be found naturally in about 10 % of left-handers and again is therefore not that unusual even today. The use of his left hand can be also found in the shading of his drawings, which pass from top right to bottom left. However, in works prepared for demonstration, Leonardo can be found to be writing and drawing with his right hand.

Conclusions

In critical viewing of Leonardo’s anatomical drawings, it is important to keep in mind the considerations discussed in this chapter. Most are not finished drawings like those found in the de Fabrica of Vesalius or even the works of Mundinus. The extant pages of Leonardo’s anatomical notes are a mixture of work in progress and developing ideas, with perhaps some completed work. Both animal and human anatomy is present, and most importantly, it is likely that a significant amount of the work has been lost. What we have left is simply a collection of pages from notebooks that have been disassembled. They represent work carried out over at least three decades and added to in different periods. They contain ad hoc notes as well as high-quality drawings, with occasional household scribbles. Not only do these pages tell us something of the breadth and depth of work that Leonardo had completed and the knowledge that he had derived from it, but they also shed a chink of light on his daily life. The humanity to be found in them is informative and sometimes amusing and moving.

The reader will likely find other examples of Leonardo’s many uses of drawing, but it is my hope that this general discussion will open the eyes of those coming anew to these wonderful visual demonstrations.

Leonardo Da Vinci Drawings

RL 12281 recto, The cardiovascular system and principal organs of a woman. Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci 1452-Amboise 1519). c.1509– 10. Black and red chalk, ink, yellow wash, finely pricked through (Lent by Her Majesty The Queen. Royal Collection © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II)

RL12592 recto, Studies of the vessels of the body, and of staircases. Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci 1452-Amboise 1519). c.1506–10. Pen and ink and red chalk (Lent by Her Majesty The Queen. Royal Collection © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II)

RL 12592 verso, The organs and vessels of the body. Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci 1452-Amboise 1519). c.1506–10. Pen and ink (Lent by Her Majesty The Queen. Royal Collection © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II)

RL 12597, The major organs and vessels. Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci 1452-Amboise 1519). c.1485–90. c.1485–90. Pen and ink with brown and greenish wash, over black chalk (Lent by Her Majesty The Queen. Royal Collection © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II)

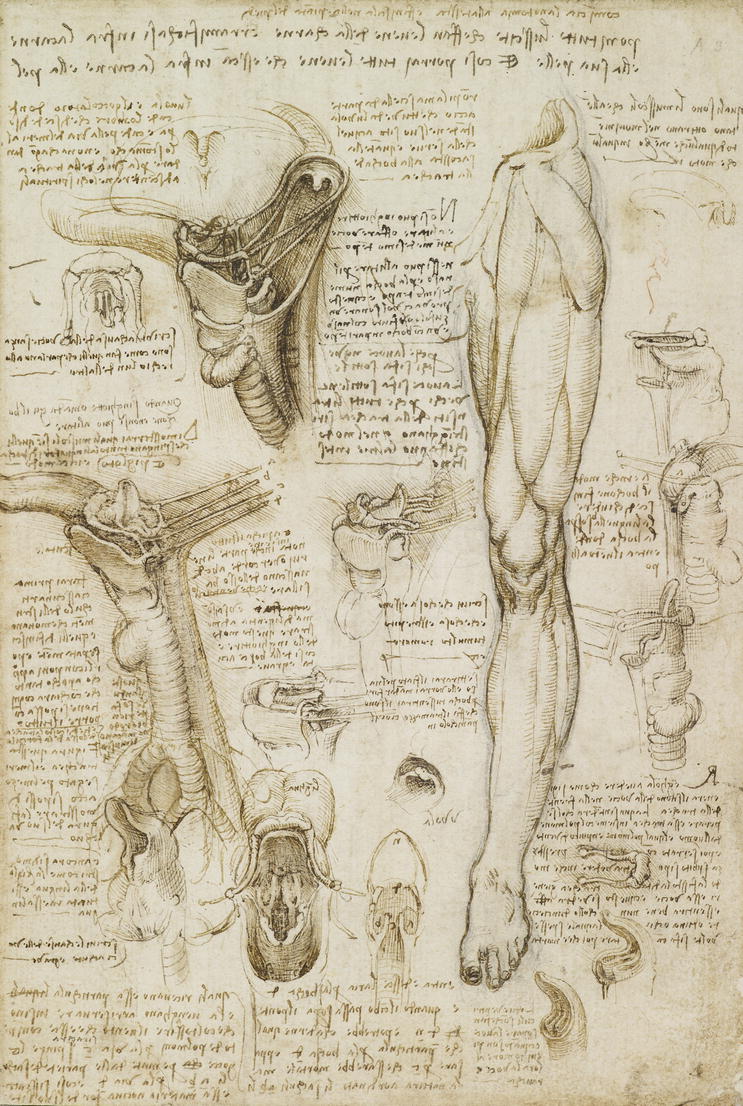

RL 19002 recto, The throat, and the muscles of the leg. Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci 1452-Amboise 1519). c.1510–11. Pen and ink with wash over black chalk (Lent by Her Majesty The Queen. Royal Collection © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II)

RL 19003 verso, The muscles of the shoulder. Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci 1452-Amboise 1519). c.1510–11. Pen and ink with wash, over black chalk (Lent by Her Majesty The Queen. Royal Collection © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II)

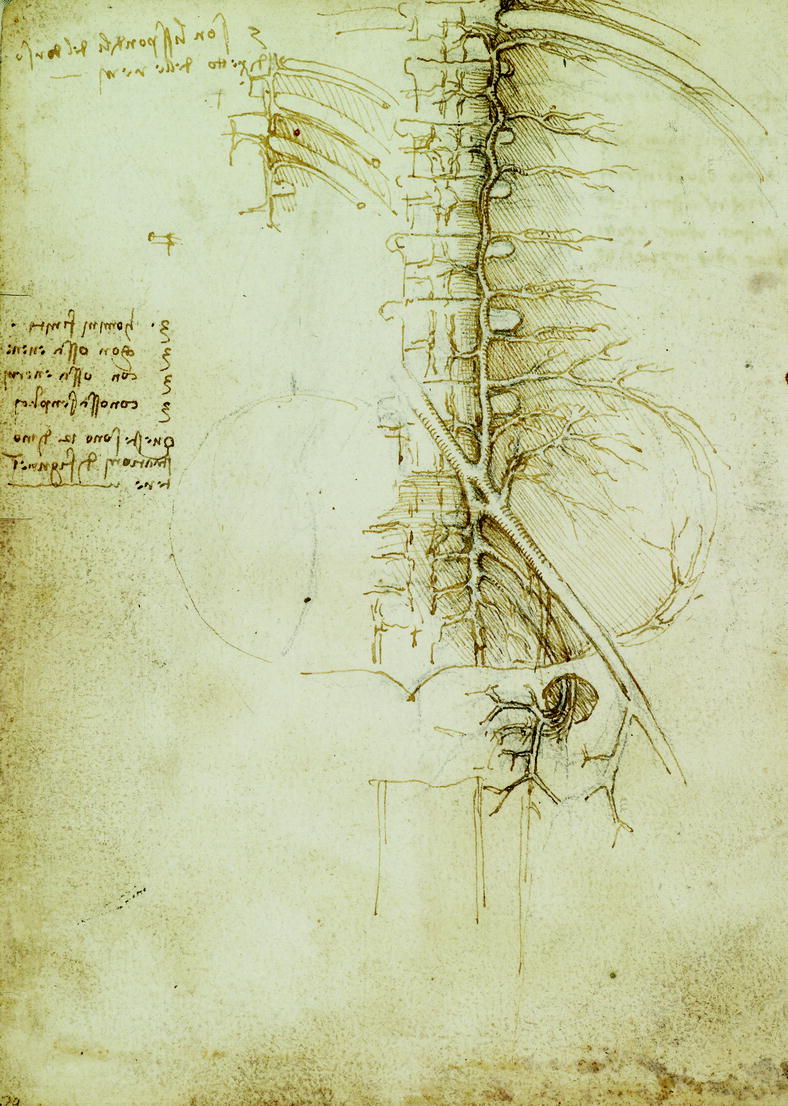

RL 19023 verso, The veins of the pelvic and lumbar region. Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci 1452-Amboise 1519). c.1508. Pen and ink over black chalk (Lent by Her Majesty The Queen. Royal Collection © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II)

19023v (B 6 v). Pen and brown ink (two shades) over traces of black chalk. | |

[Fig. 1, 2] | [Fig. 1, 2] |

[I] 5 son lisspondjli del dorso | dj retto delle renj – | [I] There are five vertebrae of the back directly in the loins. |

[II] 3 · homjni finjtj | [II] three men finished |

3 chon ossa euene | three with bones and veins |

3 con ossa eneruj | three with bones and nerves |

3 con ossa senplicj | three with bones alone |

Queste sono 12 djmo|strationj dj figure ī|tere – | These are 12 demonstrations of the whole [human] figure. |

RL19027 verso, Notes on the death of a centenarian. Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci 1452-Amboise 1519). c.1508. Pen and ink over traces of black chalk. Lent by Her Majesty The Queen. Royal Collection © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II

19027 v (B 10 v). Pen and brown ink over black chalk. | |

[Fig. 1, 2] | [Fig. 1, 2] |

[I] Larteria ella uena che ne vechi sasstende infralla milza | el fegato · sifa dj tanta grossezza dj pelle chella serra il | transito delsangue che viene dalle vene mjseraice · | perle quali esso sanghue (sa) trasscorre al fegato e al core | e alle due vene magori e per conseguēza per tutto ilcorpo | e ttali vene oltre alloingrossamēto dj pelle crescano | inllungheza essissatorcigliano auso dj bisscia e il fe|gato perde lomore (che) del sangue che dacquesta li era | porto onde esso fegato sidjsecha effassi amodo dj crus|sca cōgelata si incolore come in materia in modo | che con pocha confregatione chesopra esso sifaccia | essa materia chede [sic: chade] in minute particule come se|gatura ellasscia leuene e arterie elle vene del fiele | e dellonbelicho cheperla porta del fegato inesso fegato | entravano rimāgano tutte spogliate della mate|ria desso fegato avso della (seme) meliga ossagina | quādo ne spichati li sua granj – | [I] The artery and vein which in the old extend between the spleen and the liver generate so thick a coat that it closes the passage of the blood which comes from the mesenteric veins through which blood passes to the liver and heart and to the two greater vessels [aorta; vena cava], and consequently through the whole body. And these veins, as well as thickening the coat, grow in length and become twisted like a snake, and the liver loses the humours of the blood which was carried there by the vein. Whence the liver is desiccated and becomes like congealed bran both in colour and substance so that when but a little friction is made on it this substance falls away in minute particles like sawdust leaving behind the veins and arteries. And the bile ducts and the vein from the umbilicus, which enter the liver through the porta hepatis, remain wholly deprived of liver substance like millet or broom-corn when their grains have been pulled off. |

[II] Jlcolon (ne) ellaltre interiori ne vechi molto siristrī|gano e ottrovate loro pietre nelle vene che passa | sotto le forchole delpetto lequali erā grosse come ca|stagnje dj colore efforma djtartufi over di loppa | o marogna djferro le quali pietre erā durissime | come essa marognia e auea fattj sacchi apicha|ti alle dette vene amodo dj gozzj – | [II] The colon and other intestines in the old are very contracted. And I have found stones in the veins which pass beneath the forks of the chest [clavicles] which were as large as chestnuts, of the colour and shape of truffles or of dross or iron clinkers, which stones were very hard, like clinkers, and had formed bags attached to the said veins like goitres. |

[III] ecquesto vechio dj poche ore ināzi lasua morte mj djsse lui | passare cēto anni e chenonsi sentiua alcū manchamēto ne|la persona altro che deboleza e cosi stādosi assedere sopra | vno letto nello spedale djscā [sic: di santa] maria nova djfirēze sanza al|ltro movimeto osegnjo dalcuno accidēte passo dj questa vita – e io ne feci notomja per uedere lacausa djsi dolce morte la qual|le trovai venjre mene per mācamēto djsangue (ch) e arteria che | notria ilcore elli altri mēbri inferiori li quali trouai moltj | aridi (sec) stenuati essechi lacqual notomja djscrissi assa|i diligente mēte e cō grā facilita peressere priuato djgrasso | edjomore che assai inpedjsce lacognitione delle parte laltra | notomja fu dū putto dj 2 annj nelquale trovai ognj cosa | cōtra < r > ia acquella del uechio – | [III] And this old man, a few hours before his death, told me that he was over a 100 years old and that he felt nothing wrong with his body other than weakness. And thus, while sitting on a bed in the Hospital of Santa Maria Nuova in Florence, without any movement or other sign of any mishap, he passed out of this life. And I made an anatomy of him in order to see the cause of so sweet a death. This I found to be a fainting away through lack of blood to the artery which nourished the heart, and other parts below it, which I found very dry, thin and withered. This anatomy I described very diligently and with great ease because of the absence of fat and humours which greatly hinder the recognition of the parts. The other anatomy was on a child of 2 years in which I found everything contrary to that of the old man. |

[IV] livechi che vivano | cōsanjta moiano per | charesstia dj nutrimē|to e cquessto acha|de perche (il) ellie he | risstretto alcōtinv|o il transito alle | vene mjseraice | per lo ingrossamē|to della pelle desse | vene succiessi | vamēte insino | alle vene chapi|llari le quali sō | leprime che inte|ramēte sirichi|vdano e dacque|sto nasscie chel|li vechi temā pi|v ilfreddo chel|li giovanj e che | quellj chessō mol|ti vecchi anno | la pelle dj cholor | dj legnjo o di cas|tagnja seccha | perche tal pelle e cqa|si [sic: quasi] altucto priva|ta dj nutrimēto | [IV] The old who live in good health die through lack of nourishment. And this occurs because the passage of the mesenteric veins is continually constricted by the thickening of the coats of these veins successively as far as the capillary veins, which are the first to be completely closed. And from this it comes about that the old fear the cold more than the young; and that those who are very old have skin the colour of wood or dried chestnut because this skin is almost completely deprived of nourishment. |

ettale tonicha dj | vene fa nnellomo chome nelli pome|rancj (leqa) alle | quali tāto piu in | grossa lasscorza | e djmjnuissciela | mjdolla quātop|piu sifanno vec|chi essettu djraj | chello ingrossamēto | delsangue nō corre | perlevene quessto no|ne vero perche il sanghue non@grossa nelle vene perche al cōtinuo more errinasscie | And this coat on the vessels acts in man as it does in oranges, in which as the peel thickens so the pulp diminishes the older they become. And if you say that it is the thickened blood which does not flow through the vessels, this is not true, because blood does not thicken in the vessels since it continually dies and is renewed. |

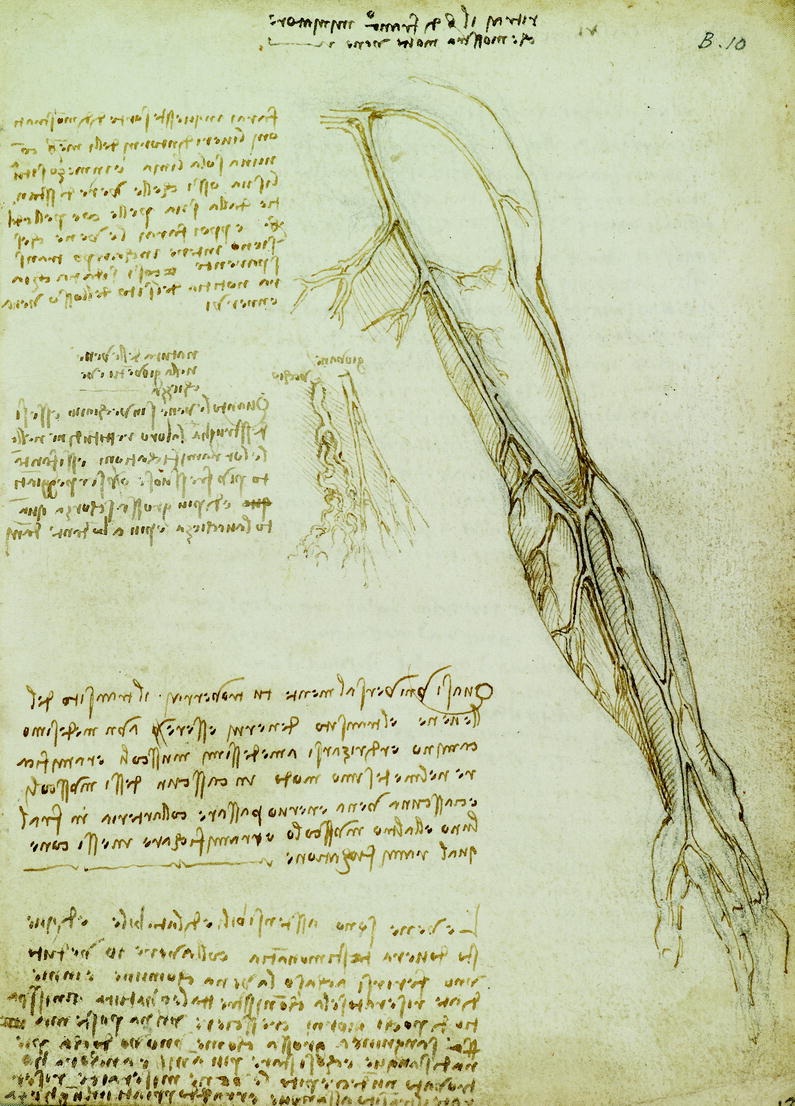

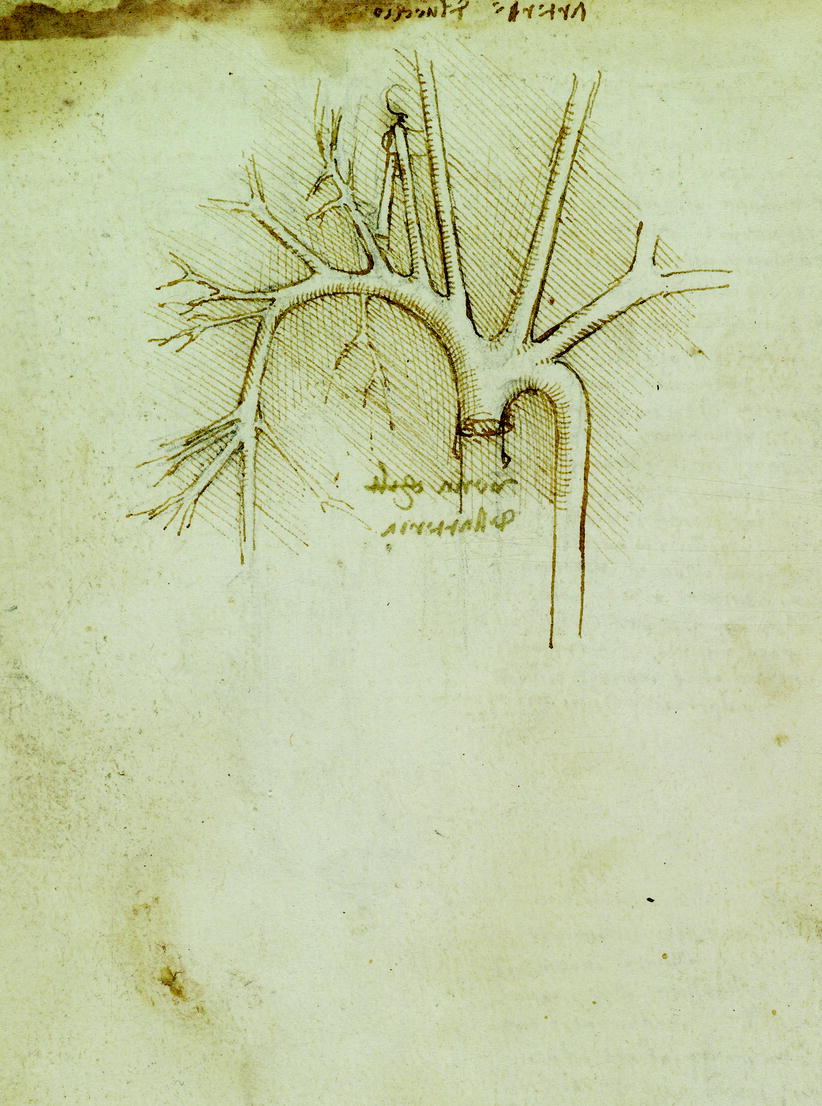

RL 19027 recto, The veins of the arm. Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci 1452-Amboise 1519). c.1508. Pen and ink over traces of black chalk (Lent by Her Majesty The Queen. Royal Collection © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II)

19027 r (B 10 r). Pen and brown ink (two shades) over traces of black chalk. 192 × 141 mm. | |

[I] ri ritraj il braccio dj francº mjnjatore | che mosstra molte vene – | [I] Portray the arm of Francesco the miniaturist which shows many veins |

[Fig. 1] | [Fig. 1] |

[II] Quasi vniversalmente tu troverraj · il transito del|lle uene el transito deneruj essere (v) avn medesimo | camjno er < a > djrizarsi a medessimj musscoli eramjfica|re nelmedesimo modo in casscun dessi mvsscolj | e ciasscuna vena eneruo passare collarteria in fral|luno ellaltro mvsscolo erramjfichare inessi cone|qual ramj fichatione – | [II] You will find almost universally that the passage of the veins and nerves is along the same path, and is directed to the same muscles, and ramifies in the same way in each of these muscles. And each vein and nerve passes with the artery between one and another muscle and ramifies within it with equal ramification. |

[III] Le vene sono asstensibili e djlatabile e dj que|sto donera testimonātia collavere io veduto | vno ferirsi achaso la vena chomune e inme|diate riseratosela chōnjsstretta leghatura einisspa|tio dj pochi giornj cressciere vn na poste ma (ro|ssa) sanguinea grossa chome vnovo docha pie|na dj sangue e chosi stare piu ānj// e anchora ho | trovato nū decrepito le vene mjseraice riser|rate iltrāsito alsangue erraddoppiati inlūgheza | [III] Veins are extensible and dilatable. And testimony of this is given by my having seen a man who by chance was wounded on the common vein [? median cubital vein] and it was immediately bound up with a tight bandage. In the space of a few days there grew up a [red] sanguineous abscess as large as a goose’s egg, full of blood; and so it remained for several years. I also found in a decrepit old man the mesenteric veins obstructing the passage of blood, and doubled in length. |

[Fig. 2] giovane | [Fig. 2] youth |

[Fig. 3] vechio | [Fig. 3] old man |

[IV] natura delle vene | nella giovētu e ve|chiezza – Quanto le vene sinvechiano esse si | desstrughā laloro rettitudjne nelle | le lor ramjfichationi essifan tā|to piv fressuose over serpeggiāti | (qua) e dj piu grossa schorza quā|to lauechieza e piu abōdante dānj | [IV] The nature of the veins in youth and age As the veins grow old they destroy the straightness of their ramifications and they produce as much more tortuosity or windings, with thicker coats, as age is more abundant in years. |

[V] faraj in quesste sorte djdjmōstrati|onj liueri djntornj delli mēbri cō|nuna sola linja e in mezo situa | lisua ossi cholle vere djsstan|tie dalla sua pelle coe pelle del | · braccio · eppoi faraj le vene ches|sieno intere inchanpo trans|sparente e cosi sidara chia|ra notitia delsito dellosso vena | ennervi | [V] In this kind of demonstration you will make the true contours of the limbs with a single line; and in the middle place the bones at their true distances from the skin, that is, the skin of the arm. And you will do the veins which should be complete in a transparent field of vision; and in this way clear knowledge of the position of the bone, vein and nerves will be given. |

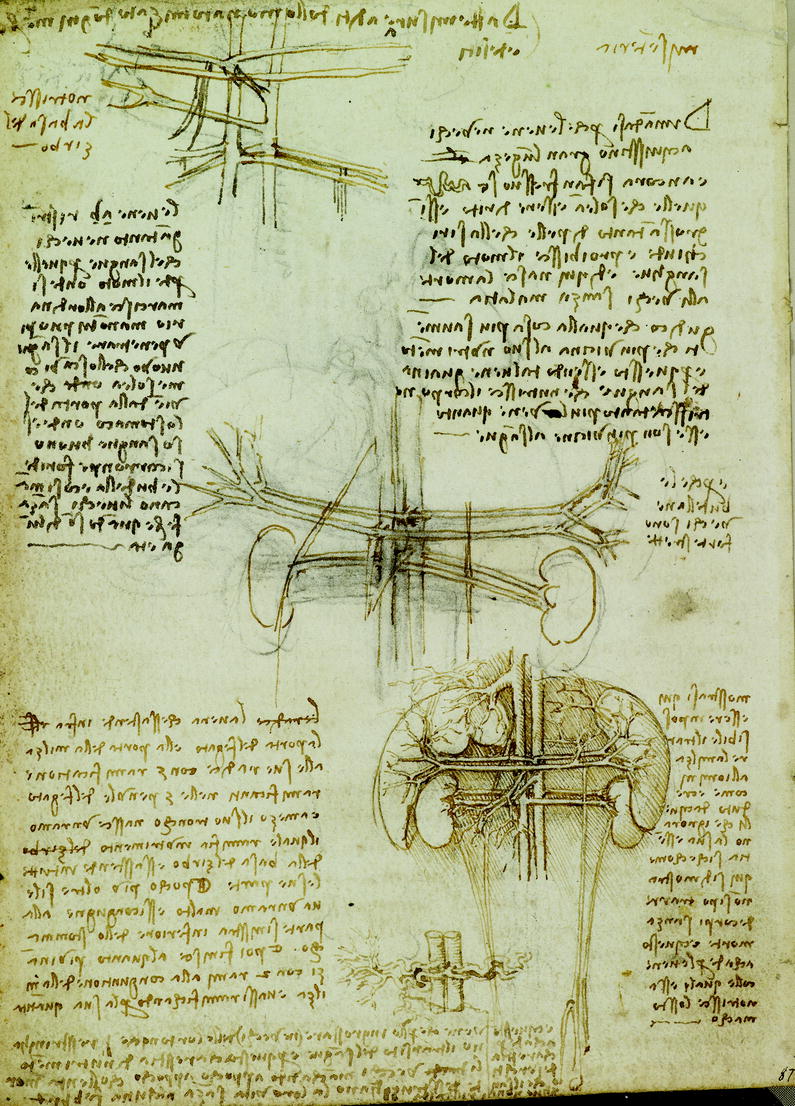

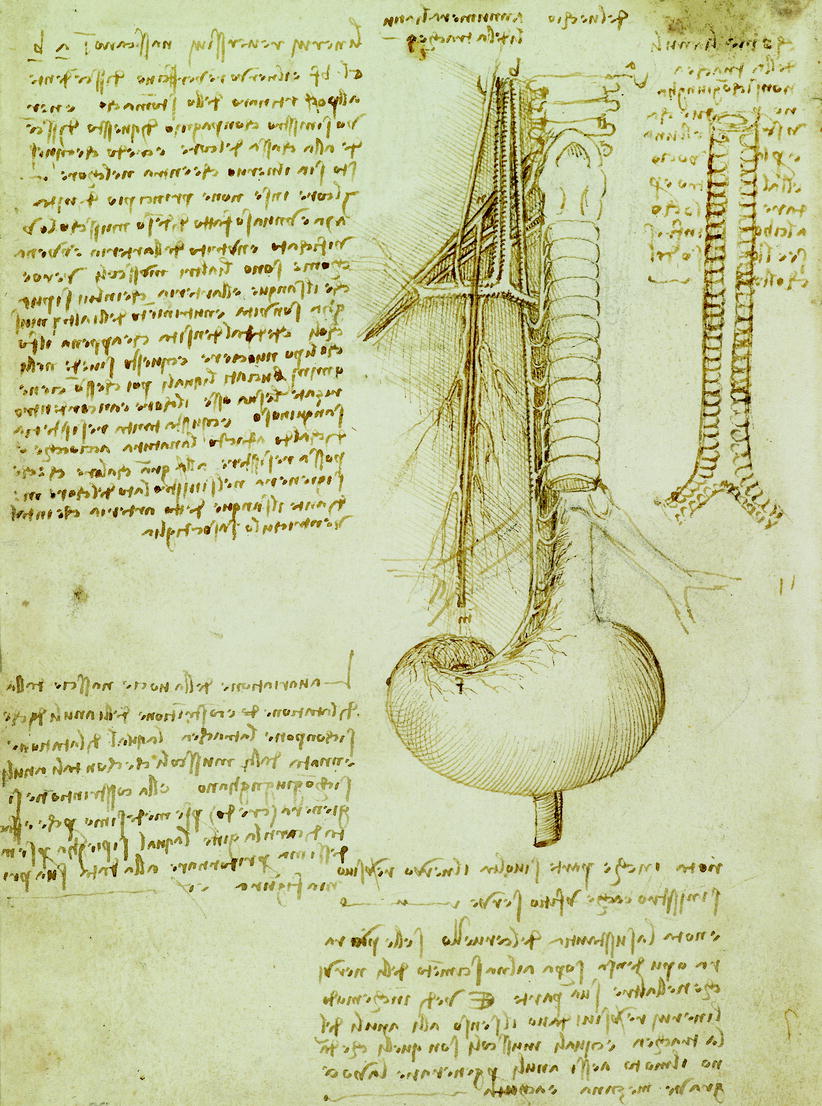

RL 19028 verso, The vessels of liver, spleen and kidneys. Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci 1452-Amboise 1519). c.1508. Pen and ink over black chalk (Lent by Her Majesty The Queen. Royal Collection © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II)

RL 19028 recto, The heart compared to a seed. Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci 1452-Amboise 1519). c.1508. Pen and ink over black chalk (Lent by Her Majesty The Queen. Royal Collection © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II)

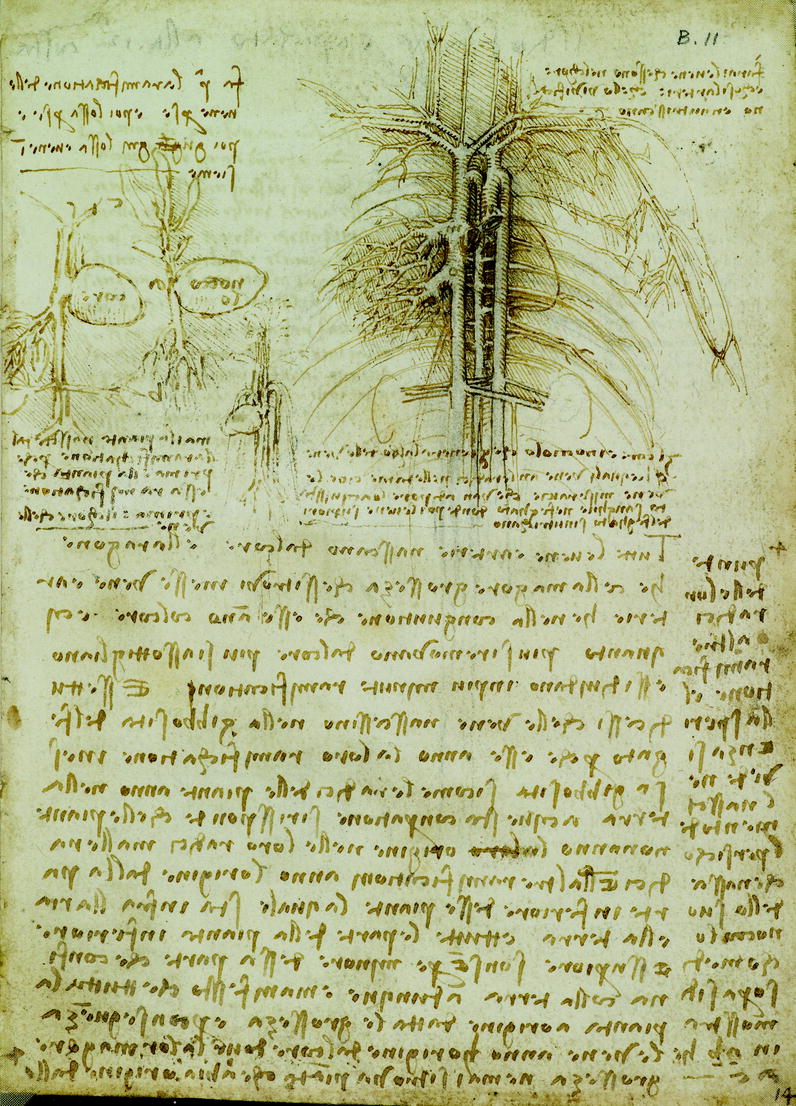

19028 r (B 11 r). Pen and brown ink (two shades) over traces of black chalk. 192 × 140 mm. | |

[I] Il djaf[ran]a e apichato alla 12a costa | [I] The diaphragm is attached to the 12th rib. |

[II] farai leuene chessono nelchore | echosi larterie chello vivifjca|no ennutrisscano | [II] Draw the veins which are in the heart, and also the arteries, which vivify and nourish it. |

[Fig. 1] m n o | [Fig. 1] m n o |

[Fig. 2] nocco|lo a b c | [Fig. 2] nut a b c |

[III] Tutte le uene e arterie nasscano dalcore e llaragone | he c < h > ella magore grosseza chessitrovi inesse vene e ar|terie he nella conguntione che esse āno col core · e cq|quanto piu siremovano dal core piu si assottigliano | essj djujdano inpiu mjnute ramjficationj E sse ttu | djcessi chelle vene nasscessino nella gibbosita del fe|gato perche esse anno la loro ramjfichatione ines|sa gibbosita sicome le radjci delle piante anno nella | terra cque sta conparatione sirissponde chelle piante | nonanno la(loro) origine nelle loro radjci ma lle ra|dici ellaltre ramjficationj anno lorigine dalla pa|rte inferiore desse piante la quale sta infra llaria | ella terra ettutte le parte della pianta inferiore | e ssuperiore sonsē pre mjnore dessa parte che confi|na colla terra adunque e manjfessto che ttutta la | pianta a origine datta le grosseza e perconseguēza | le vene anno horigine dal core doue la lor magore | grosseza ne maj sitrova piāta che abia origine dalle 4| [^ –]4 punte | delle lor | radjci | o oltre | ramjfica|tione el|lla speri|enza si | vede ne|l nasscj|mento de|l persicho | che nassce | dello suo | noccolo | chomedj | sopra sidj|mosstra | in a b he | a c –[− ^] | [III] All the veins and arteries arise from the heart; and the reason is that the biggest veins and arteries are found at their conjunction with the heart. And the more they are removed from the heart the finer they become, and they divide into very small branches. And if you say that the veins arise in the gibbosity of the liver because they have their ramifications in this gibbosity, just as the roots of plants have in the earth, the reply to this comparison is that plants do not have their origin in their roots, but the roots and other ramifications take origin from that lower part of the plant which is situated between the air and the earth. And all the lower and upper parts of a plant are always less than this part which adjoins the earth. Therefore it is evident that the whole plant takes origin from such a size and in consequence the veins take their origin from the heart where they are biggest. Never does one find a plant which has its origin from the tips of its roots or other branches; and this is observed by experience in the sprouting of a peach which arises from its nut as is shown above at a b and a c. |

[Fig. 3] core | [Fig. 3] heart |

[Fig. 4] | [Fig. 4] |

[IV] mai la pianta nasscie dal|llaramjfichatione perche | prima e lla pianta che | essa ramj fichatione | e prima e ilchore chelle | vene – | [IV] A plant never arises from its branches, for the plant exists before the branches and the heart exists before the veins. |

[V] Jl core einocciolo che gienera lalbero delle vene | (e) Lequalj vene an leradici nelletame cioe le | vene mjseraicie che van adjpore loacqujssta|to sanghue nefeghato donde poi le uene superiori | del feghato sinutrichano – | [V] The heart is the nut which generates the tree of the veins; which veins have their roots in the manure, that is the meseraic [mesenteric] veins go on to deposit the blood they have acquired in the liver, whence then the upper veins of the liver [hepatic veins] are nourished. |

[VI] fa pa laramjfichatione delle | uene perse e poi lossa perse e | poi gu(gli)gnj lossa e uene ī|sieme – | [VI] Draw the first ramification of the veins by itself, and then the bones by themselves, and then join the bones and the veins together. |

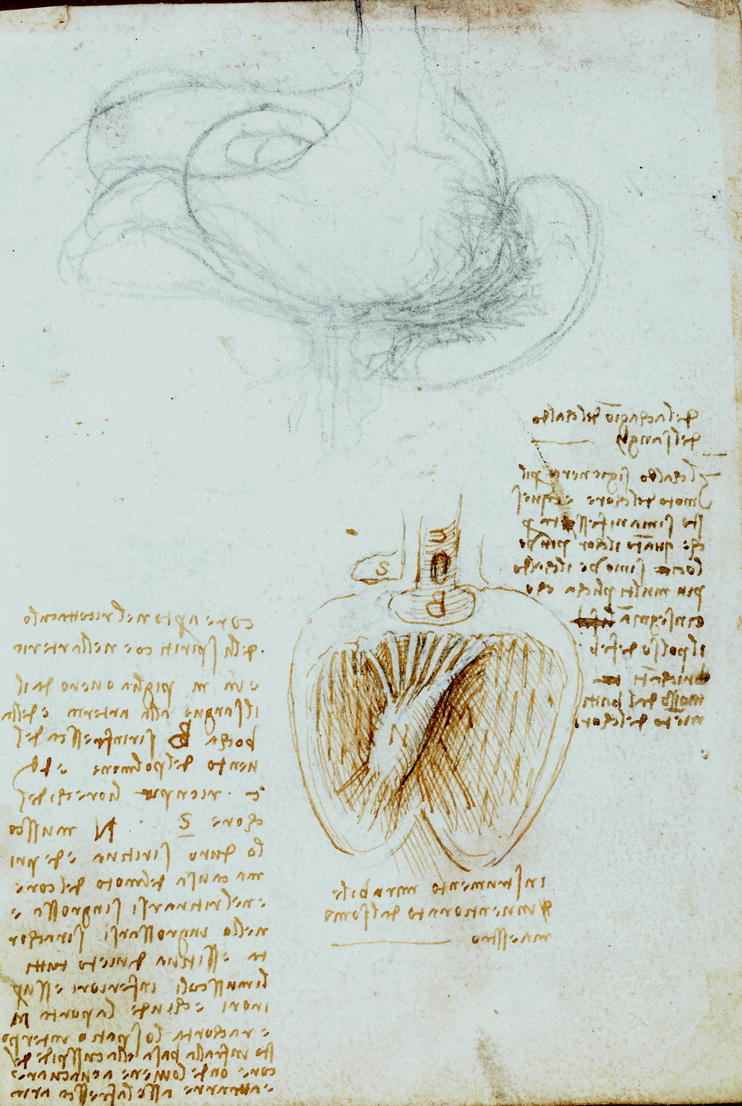

RL 19029 recto, The stomach, and the heart. Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci 1452-Amboise 1519). c.1508. Pen and ink with black chalk (Lent by Her Majesty The Queen. Royal Collection © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II)

19029 r (B 12 r). Pen and brown ink (two shades) with black chalk. 191 × 138 mm. | |

[Fig. I] | [Fig. I] |

[I] delachagiō del chaldo | del sangh < ue > − Jl chaldo sigienera peril | moto del chore e cques|sto simanifessta per|che quāto ilchor piu ve|locie simove ilchaldo | piu multi plicha cho < me > | cinsegnjā (lifeb) | il polso defeb|brichāti (n) | mosso dal battj|mēto delchore | e | [I] On the cause of the heat of the blood The heat is generated by the movement of the heart; and this is evident because the more quickly the heart moves the more the heat multiplies, as the pulse of febrile persons moved by the beating of the heart teaches us. |

[Fig. 2] C S B M N | [Fig. 2] C S B M N |

[II] instrumento mirabile | (d) inuentionato dalsomo | maestro – | [II] Admirable instrument, invented by the Supreme Master |

[III] core aperto nel ricettaculo | dellj spiriti coe nellarteria | e in m piglia o uero da il | ilsangue alla arteria e della | bocha B sirinfressca del | uento del polmone eddj |· c · rienpie liorechi del | chore S · N mussco|lo duro siritira e de pri|ma causa delmoto del core | e nel ritirarsi singrossa e | nello ingrossarsi sirachor|ta essitira djrieto tutti | li musscoli inferiori essuper|irori e chiude la porta M | e rachorta lo spatio interpo|sto infralla basa ella cusspide del | core onde loujene a euacuare | e attrarre asse lafressca aria | [III] The heart, opened in the receptacle of the spirit, that is, the artery [left ventricle]. And at M it either takes the blood or gives it to the artery; and by the mouth B [mitral orifice] it is refreshed by the wind of the lungs; and through C it fills the auricles of the heart S.N, a hard muscle, contracts and is the primary cause of the movement of the heart, and in contracting it enlarges, and in enlarging it shortens and draws back all the muscles below and above it, and closes the gate M [mitral valve] and shortens the distance interposed between the base and the apex of the heart, whence it comes to empty itself, and to attract to itself fresh air. |

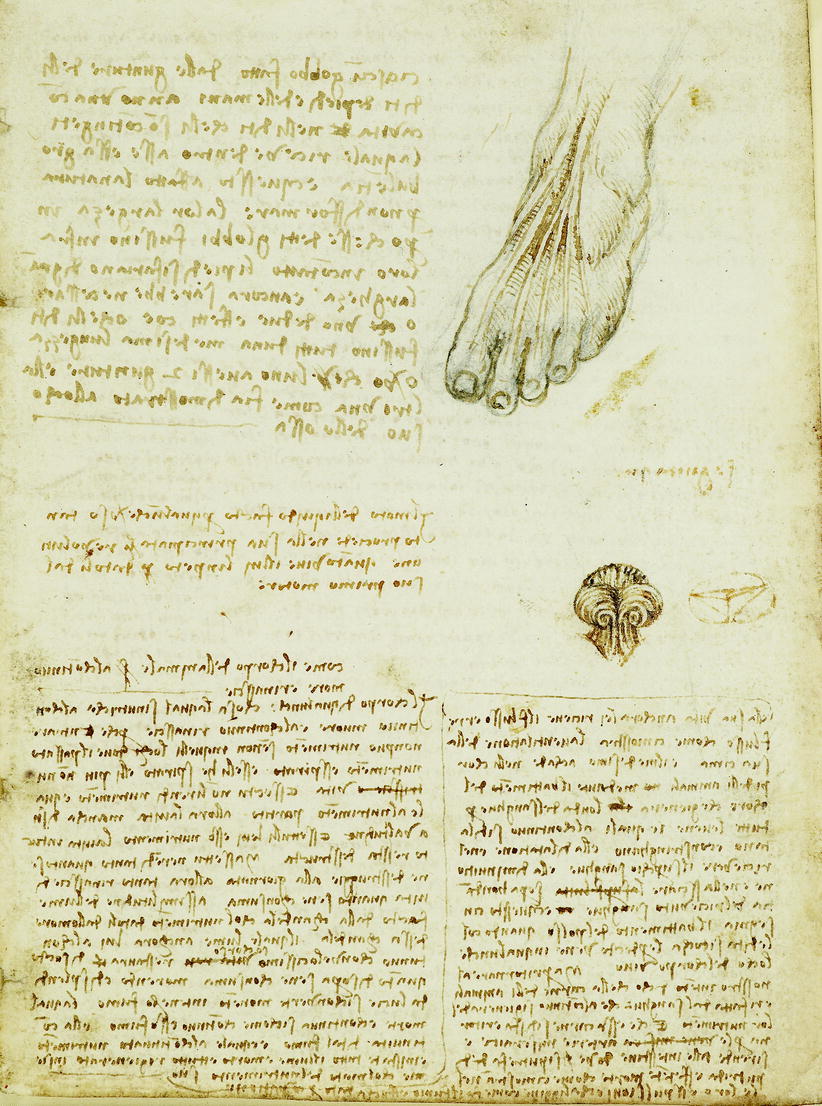

RL 19045 recto, A study of the tendons of the foot, etc. Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci 1452-Amboise 1519). c.1508. Pen and ink over traces of black chalk (Lent by Her Majesty The Queen. Royal Collection © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II)

19045 r (B 28 r). Pen and brown ink (three shades) over traces of black chalk. 192 × 139 mm. | |

[Fig. 1] | [Fig. 1] |

[I] ciascū gobbo fatto dalle gunture dellj | djti depiedj e delle mani anno vna cō|cavita (de) nelli djti chellj sō cōtingēti | la quale riceve dentro asse essa gro|bulētia e cquessto affatto la natura | per non djffor mare la lor largeza in|pero chesse dettj globbi fussino infra | loro incōtatto li piedj sifariano dj grā | largheza · e ancora sarebbe necessari|o (che) vno de due effettj coe ochelli djti | fussino tuttj duna medesima lungezza | over che (v) luno auessi 2 gunture ella|ltro vna come fia djmosstrato allocho | suo delle ossa – | [I] Each protuberance made by the joints of the digits of the feet and hands has a hollow in the digits contiguous to it which receives into itself this rounded protuberance; and Nature has done this in order not to deform their width. For if the said protuberances were in contact with one another the feet would become of great width, and one of two further effects would necessarily occur; that is, either the digits would all be of the same length, or one would have two joints and the other one, as is demonstrated in its place on the bones. |

[II] seguita qua | [II] It follows here … |

[Fig. 2, 3] | [Fig. 2, 3] |

[III] Jlmoto delliqujdo facto perqualūche verso tan|to prociede nella sua principiata (li) revoluti|one quāto viue illuj linpeto (p) datoli dal | suo primo motore | [III] The movement made by a liquid in any direction proceeds as far in its original rotation as the impetus given to it by its prime mover. |

[IV] come ilchorpo dellanjmale (s) alchōtinuo | more erinasscie – Jl chorpo dj qualunche chosa laqual sinutrjcha alchon|tinuo muore e al chontinuo rinasscie perche entrare | nonpuo nutrimēto sēnon inquellj lochi doue ilpassato | nutrimēto esspirato · esselli he spirato ellj piu nō nu | (trisscie e) vita essectu nō li rendj nutrimēto equa|le al nutrimēto partito · allora laujta mancha djsu|a valitudjne essettullj leuj esso nutrimento laujta intuc|to ressta desstructa Massettu nerēdj tanto quanto se | ne desstruggie alla giornata allora tanto rinasscie dj | ujta quanto sene chonsuma assimjlitudjne dellume | facto dalla chandela chol nutrimēto datolj dallomore | dessa chandela il quale lume anchora luj alchon|tunuo chonvelocissimo (vita ren) ^sochorso^ restaura (il) dj socto | quāto djsopra sene chonsuma morendo e dj splendi|da lucie sichonverte morēdo intenebro<so> fumo laqual | morte e chontinua sichome chōtinuo esso fumo ella cō|tinuita · dj tal fumo e equale alchōtinuato nutrimēto | einjsta<n>te tutto illume e morto ettutto rigienerato insie|me chol moto delnutrimento suo [: – :] ella sua vita anchora lej ricieue ilflusso erre|flusso chome ci mosstra lauentilatione della | sua cime e ilmedesimo achade nelli chor|pi delli animali (ne) medjante il battimēto del | chore che gienera (iln) londa delsanghue per | tutte leuene le quali alchontinuo sidjla|tano econstringhano ella djlatatione enel | ricievere ilsuperchio sanghue ella djmjnuitio|ne e nellassciare (lasuperflujta) soprabondā|tia delricievuto sanghue (co) ecquessto cin|segnja il battimento del polso quando col|le djta sitocha le predecte vene in qualunche | locho del chorpo viuo Ma perritornare al | nosstro intēto djcho chella carne dellj anjmalj | e rifatta dal sanghue che alcōtinuo sigienera del | lor nutrimēto E che essa carne sidjsfa eritor|na perle (vene mjs en) arterie mjseraice e | sirende alle intesstine dove (e) siputrefa (dj) dj | putrida effetēte morte chome cimostrā nel|le loro esspulsionj e chaliggine come fa ilfumo effocha dato per cōperatione | [IV] How the body of an animal continually dies and is reborn The body of anything which is nourished continually dies and is continually reborn, for nourishment cannot enter except into those places where past nourishment has been exhausted, and if it has been exhausted it no longer (nourishes) or has life. Unless, therefore, you supply nourishment equal to the nourishment that has departed, life loses its vigour, and if you take away nourishment life is totally destroyed. But if you supply just as much nourishment as is destroyed daily, then as much life is reborn as is consumed – just as the light of a candle is made from the nourishment from the humour given it by the candle. And this light also is itself continually restored with swiftest succour from below by as much as is consumed above in dying; and in dying it is changed from bright light to dark smoke. And this death continues as long as the smoke continues; and its continuity is equal to the continuity of nourishment. And at any instant the whole light is dead and completely regenerated together with the movement of its nourishment. Its life, furthermore, receives from it flux and reflux as the to and fro movement of its tip shows us. And the same thing happens in the bodies of animals by means of the beating of the heart which generates a wave of blood through all the vessels which continually dilate and contract. And dilatation occurs on the reception of superabundant blood and diminution occurs on the departure of the superabundance of the blood received. This the beating of the pulse teaches us when we touch the aforesaid vessels with our fingers in any part of the living body. But to return to our intention. I say that the flesh of animals is being continually re-made from the blood which is continually generated from their nourishment. And that this flesh is unmade, and returns through the mesenteric arteries and is supplied to the intestines where it becomes putrified into putrid and foetid death, as their expulsions and steams show us, like the smoke and fire given for comparison. |

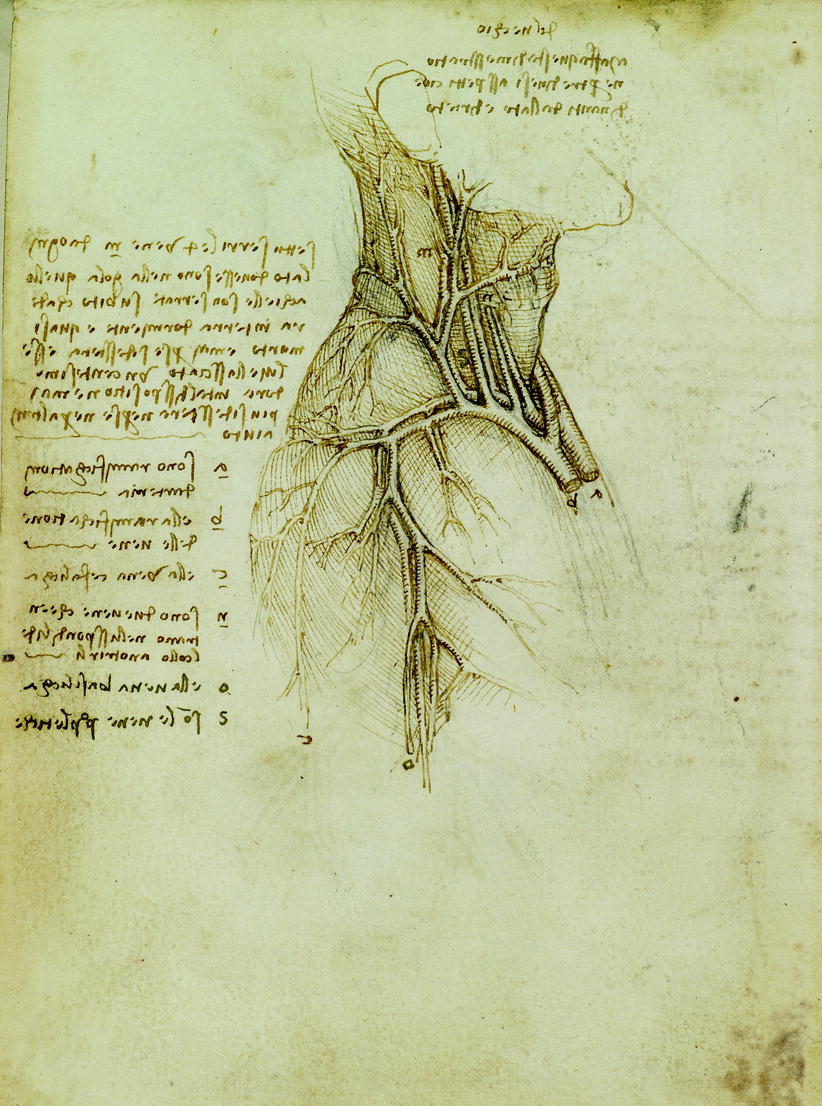

RL 19049 verso, The vessels of the neck and shoulder. Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci 1452-Amboise 1519). c.1508. Pen and ink over black chalk (Lent by Her Majesty The Queen. Royal Collection © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II)

19049v (B 32 v). Pen and brown ink (two shades) over traces of black chalk. | |

[I] del uechio Maffa questa djmosstratio|ne per tre djue < r > si asspetti cioe | djnanti dallato e djrieto | [I] Of the old man But make this demonstration from three different aspects, that is from the front, side, and back. |

[Fig.] a b c m n o s | [Fig.] a b c m n o s |

[II] settu serri le 4 vene m da ognj | lato douesse sono nella gola quello | achielle son serrate subito chade|ra in terra dormjente e quasi | morto e maj perse sidesstera esse | luj e llassciato vn centesimo | dora intal djsspositione maj | piu sidesstera neperse neperaltruj | aiuto – | [II] If you close the four vessels m on each side where they are in the throat, he who has them closed will fall to the ground immediately in sleep [coma] as if dead and he will never wake up on his own. And if he is left for one-hundredth of an hour in such a condition he will never wake again, neither on his own nor with the help of others. |

[III] a sono ramjfichationj | darteria – b ella ramjfichatione | delle uene – c ella vena cefalicha n sono due uene che en|trano nellisspondjli de|l collo anotrirli – o ella uena basilicha s sō le uene p^o^pletiche | [III] a are the ramifications of the artery b is the ramification of the veins c is the cephalic vein n are the two vessels which enter the cervical vertebrae to nourish them o is the basilic vein s are the apoplectic vessels |

RL 19050 verso, The distribution of the right vagus and right phrenic nerves. Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci 1452-Amboise 1519). c.1508. Pen and ink over black chalk (Lent by Her Majesty The Queen. Royal Collection © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II)

RL 19050 recto, The arteries of the shoulder. Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci 1452-Amboise 1519). c.1508. Pen and ink over black chalk (Lent by Her Majesty The Queen. Royal Collection © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II)

19050r (B 33 r). Pen and brown ink (two shades) over traces of black chalk. 193 × 133 mm. | |

[I] arterie deluechio | [I] Artery of the old man |

[Fig.] | [Fig.] |

[II] vena (chili) dellarteria | [II] Vessel of the artery |

RL 19051 recto, The vessels and nerves of the neck. Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci 1452-Amboise 1519). c.1508. Pen and ink. Lent by Her Majesty The Queen. Royal Collection © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II

19051r (B 34 r). Pen and brown ink over traces of black chalk. 191 × 135 mm. | |

[I] deluechio | [I] Of the old man |

[Fig. I] | [Fig. I] |

[II] deluechio | [II] Of the old man |

[Fig. 2] a b | [Fig. 2] a b |

[III] neruo djscēdēte alla cassa delcore | in mezo allarteria euena – | [III] Nerve descending to the capsule of the heart between the artery and the vein. |

[IV] a ella vena b ellarteria | [IV] a is the vein b is the artery |

[V] nota selle piu grossa larteria | chella vena olla vena chellarte|ria eilsimjne [sic: simile] fa ne fancullj | govanj e vechi e massci effe|mjne eanj mali dj terra eda|ria e dacqua – | [V] Note whether the artery is bigger than the vein, or the vein that the artery; and do the same in children, young and old, both male and female, and animals of the earth, air and water. |

RL 19054 verso, The lungs. Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci 1452-Amboise 1519). c.1508. Pen and ink over traces of black chalk (Lent by Her Majesty The Queen. Royal Collection © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II)

RL 19062 verso, Notes on the ventricles of the heart. Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci 1452-Amboise 1519). c.1511–12. Pen and ink (Lent by Her Majesty The Queen. Royal Collection © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II)

19062 v (C I 3 v). Pen and brown ink | |

[Fig.] a b c d e | [Fig.] a b c d e |

[I] Del uētriculo desstro auendo il desstro ventriculo inferiore piu a rendere del sangue preso che rrite|nerne e ordjnato le tre sue porte le qualj si serrā dj dentro infi [sic: infino] che esse non siserrī | mai cō perfetto serramēto sennō quādo iluentriculo nel suo ristrignersi (non a) | sitrova auere riseruato quella quātita dj sangue che llui vol ritenere e al|lora essendo interamē [sic: interamente] serrate esse tre porte allora le pariete siserāno ^c^on tā|ta potentia intorno alrimanēte del fugito sangue chelli e fforza che grā parte dj | quello sifugha desso vētrichulo e penjtri per li meati del parie(de)te dj mezo eppe|njtri nel sinistro ventrichulo ilquale assottigliato nella penetratione dellj | stretti meati siconverte (quasi) in jsspiriti vitali lassciando ongnj grosseza | inesso desstro vētriculo laqual grosseza – | [I] On the right ventricle The right ventricle, having to give back more of the blood taken in than it retains, has its three doors [tricuspid valve-cusps] which are closed from within so arranged that they never shut with perfect closure until and unless the ventricle in its contraction is found to have retained that quantity of blood which it needs to retain. Then these three gates [cusps] being completely closed, the walls [of the right ventricle] close with such power round the remainder of the escaped blood with such a force as to make a great part of it issue from this ventricle and penetrate through the meati [pores] of the middle wall [interventricular septum] and so penetrate into the left ventricle. This [blood] subtilised by penetrating through the narrow meati is converted into vital spirits leaving all gross material in the right ventricle, which coarse material … |

[II] della grosse(za) vissciiosita dj sangue | ce siragva nel desstro vētriculo · Jl sangue del destro ventriculo cherimane della sottiglieza del sangue che | penetra nel uentriculo (desstro) sinjsstro e viscio | e cqualc < h > e parte se ne cō|pone immjnute fila assimjlitudine del uermo deluētriculo dj mezzo alcer|vello e cqueste tali fili simultiplicano ^a modo di grossa e corta stoppa^ e allungho andare (in modo) e ssavi|luppano intorno alle corde de pa$jculi chesserano il uentriculo desstro | in modo che nella vechieza delli anjmalj la porta (e) nosipo bē serrare | e grā parte del sangue che dovea penetrare le strette porosita del pariete | di mezo nelsinjstro vētriculo alla creatiō depredetti spiriti sifugge per le | porte nō ben serrate (e) nel destro ventriculo superiore e per questo allj | vechi mācano tutti li spiritj esspesso (p) moiano parlando – | [II] On the gross viscosity of the blood which collects in the right ventricle The blood in the right ventricle which remains behind after the subtilised blood penetrates into the left ventricle is viscous and a certain part of it is composed into minute fibres [fibrin threads] like the worm of the middle ventricle of the brain [the choroid plexus in the third ventricle]. And these fibres multiply like thick short tow and lengthen and wrap themselves around the cords of the membranes [chordae tendineae of the valve-cusps] which close the right ventricle [tricuspid valve] in such a way that with the ageing of the animal the orifice [of the valve] cannot close well and a large part of the blood which ought to penetrate the narrow porosities of the middle wall into the left ventricle for the creation of the above-mentioned spirits, escapes through the imperfectly closed valve orifice into the right upper ventricle [right atrium]. For this reason all the spirits are insufficient in the aged and they often die whilst speaking. |

[III] dellufitio dello inferiore e ssuperiore | ventriculo desstro – Lufitio del(su)llo inferiore essuperiore ventriculo desstro loinferiore | da in djposito il sangue al superiore ilquale proibiva illuj ilrisstringnersi e nō si potrebbe maj poi djlatarsi senō riauessi ilsangue che prima | rienpiena la sua capacita dal uentriculo superiore Il quale e atto a ristrī|gnersi perche non po auere aria chello riēpiessi ∂ e llaria © che sochorre il | ilocho che ochupaua il uentriculo superiore quando tenea indjposito il sā|gue del ristretto ventriculo inferiore corre a reienpiere illoco del | vētriculo superiore quādo sirisstrigne ed e dj quella della cassula del | core e essa casssula dando della sua aria allocho lassiato dal ri|strignere desso superiore vētriculo: e restaurata dal tirare per la | trachea piu aria nel polmone che non era ilsuo solito e per ques|sto senpre laria chessitira nelpolmone nō po essere equale – | [III] On the function of the lower and upper right ventricle The function of the lower and upper right ventricle. The lower one gives a deposit of the blood which prevented it contracting to the upper one, and afterwards it would never be able to dilate unless it got back from the upper ventricle the blood which first filled its capacity. This [upper ventricle] is ready to contract because it cannot get air to fill it. Air which takes the place occupied by the upper ventricle when it holds the blood deposited in it by the contraction of the lower ventricle, flows in to replace the upper ventricle when it contracts, and it comes from that in the capsule of the heart [pericardium]; and this capsule having given away its air to the place left by the contraction of the upper ventricle is restored by drawing more air into the lung through the trachea than usual; therefore the air drawn into the lung cannot always be equal. |

[IV] perche laria chessi tira nel polmone | no po senpre essere dequale mjsura | [IV] Why the air which is drawn into thelung cannot always be of equal measure |

RL 19062 recto, The atria and ventricles of the heart. Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci 1452-Amboise 1519). c.1511–12. Pen and ink (Lent by Her Majesty The Queen. Royal Collection © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II)

19062 r (C 13 r). Pen and brown ink 288 × 215 mm. | |

[Fig.] | [Fig.] |

[I] delli vētrichuli del core | [I] On the ventricles of the heart |

Il core a quattro ventrichuli coe due (desstri e due sinjstri e) inferi|ori e (due superiori) nellasustātia del core e due superiorj for della susā|tia (superiore) del core e dj questi ne due desstrj e due sinjsstrj ellj | destri son assai magiori delli sinjsstri ellj superiori son separati da certi | vscioli (over porte del core) dalli ventriculi inferiori elli ventriculi | inferiori sono separatj da vn pariete poroso per il quale penetra ilsan|gue del uētriculo destro neluētriculo sinjsstro e quādo esso destro vē|triculo (si) inferiore si serra elsinjstro inferiore sapre ettira asse | ilsāgue che il destro gli (prieme in corpo) ^porge^ //. | The heart has four ventricles, that is two lower in the substance of the heart and two upper [atria] outside the substance of the heart, and of these two are on the right and two on the left. The upper ones [atria] are separated by certain little doors (or gateways of the heart) from the lower ventricles. And the lower ventricles are separated by a porous wall through which the blood of the right ventricle penetrates into the left ventricle; and when the right lower ventricle shuts, the left lower one opens and draws into itself the blood which the right offers it. |

elli ventriculi superiori | alcontinuo fanno frusso e refrusso colsangue che alcontinuo e ti|rato o sospinto (dal uno allaltr dallj) ^per lj^ vētriculi inferiori dallj superiori | e perche essi vētriculi superiori (nōte) son piu atti (ac) acaciare dj se il sā|que [sic: sangue] chelli djlata che attirarlo asse natura affatto che per il serrare | delli vētriculi inferiori (li qualj per se medesimo si serrano) che il sangue | che dj loro sifugge sia quello che djlata li uentriculi superiori li qua|li per essere lor conposti dj muscoli e pannjculo carnoso sono attj | a djlatarsi ericeuere quanto sangue illoro e sospinto od etiā attj | cō potēti musculi (atti) a ristrignersi con@peto e cacciare il sangue dj | se neljuētriculi inferiori delli quali quādo lū sapre ellaltro siserra | e il simjle fanno liuētriculi superiori in modo tale che qūdo [sic: quando] il uētri|culo destro inferiore si djlata ilsinjsstro superiore sicōstrigne e cquan|do il sinisstro ventriculo ^inferiore^ sapre ildestro superiore siserra e cosi con tale | frusso e refrusso fatto con gra celerita il sangue siriscalda essi assittigli|a effassi dj tanta caldeza chesse nō fussil sochorso dal matece (che) detto pol|mone il quale (prieme) tira laria (nel) fressca nel suo djlatarsi ella | priene [sic: prieme] e ttocha leueste delle ramjficatione delle vene elle rinfressca | esso sangue verrebbe intanta caldeza che soffocerebbe ilcore ello pri|verebbe dj ujta – | The upper ventricles [atria] continually make a flux and reflux of blood which is continually pulled or pushed through the lower ventricles from the upper. And since the upper ventricles [atria] are more suited for driving out of themselves the blood which dilates them than pulling it into themselves, Nature has so made it that by the closure of the lower ventricles (which close on their own) the blood which escapes from them is that which dilates the upper ventricles. These through being composed of muscles and fleshy membranes are suitable for dilation and for receiving as much blood as is pushed into them: they are also suited by their powerful muscles for contracting with impetus and driving out of themselves the blood into the lower ventricles, of which when one opens the other closes. And the upper ventricles [atria] do the same thing in such a way that when the right lower ventricle dilates the left upper ventricle contracts, and when the left lower ventricle opens, the right upper one closes. And so by flux and reflux made with great rapidity the blood is heated and subtilised and is made so hot that but for the help of the bellow called lungs, which draw in fresh air by dilating and pressing it into contact with the coats of the ramifications of the vessels refreshing them, the blood would become so hot that it would suffocate the heart and deprive it of life. |

Rissposta dellauersario contro al numero delli vētricu|li dicēdo quelli essere 2 e nō 4 perche (so) essi son continuati e vnj|ti insieme li 2 desstri inse effassene £ medesimo e ssimjlmēte fa il sinj|stro ∂ quj si risponde che sse li desstri e sinjstri ventriculi sono u sol | destro vn sol sinjstro ventriculo egli e (ue) necessario che in u medesi|mo tēpo essi faccino vn medesimo vfitio e nō ^nellato destro^ vfiti cōtrari come si ma|njfesta nellor frusso e refrusso e ancora selle u medesimo e nō uacha|de li usscioli neruosi chelli si(se)perino lū dallaltro esselle vnmedesi|mo e non achade che quādo vna parte sapre laltra si serra (inper) e anco|ra e provata nella essentia delli (corpi) ^menbri^ che vn medesimo mēbro e detto | quello che in medesimo tenpo fa vnmedesimo vfitio come il corpo del mā|tace o della piua ilquale (pare) ancor che paia vn medesimo colcorpo vma|no quādo essa e confiata dalluj e none pero che sieno vnjti ne faccino in un | medesimo tempo il medesimo vfitio inperoche quādo il polmō dellomo siuo|ta della sua aria il sacho della piua nel medesimo tēpo senpie della me|desima aria adūque e cōcluso li uentriculi superiori del core esser ua|ri inellj loro vfiti e nelle loro sustantie e nello loro natura da cq|quelli dj sotto edessere djuisi da cartilagine e varie sustantie interpossta | infra luno e llaltro coe il paniculo neruoso e lamolta pinguedine – | Reply to the adversary against the number of ventricles saying that they are two not four because they are continuous and united together, the two right by themselves making the same one, and the left doing likewise. Here one replies that if the right and left ventricles are one single right and one single left ventricle only, it is necessary that during one and the same time they should perform one and the same function, and not opposite functions on the right side as is manifested by their flux and reflux. Furthermore, if it is one and the same, there is no need for the membranous doors [valves] which separate one from the other; and if it is one and the same [ventricle] there is no need for one part to open when the other closes. This is further proved by the essential nature of a part of the body in that one and the same part is called that which at the same time performs one and the same function. Just as the body of a bellows or the bagpipes which may appear to be one and the same with the human body when it is inflated by it, but is not united with it, nor does it perform at the same time the same function; for when the man’s lungs are emptied of air the bag of the bagpipes at the same time is filled with the same air. Therefore it is concluded that the upper ventricles of the heart [atria] are different in their functions, in their substance, and in their nature from those below, and that they are separated by gristle and various substances interposed between one and the other, that is sinewy membrane and much fat. |

Li uētrichuli superiorj del core nō sidjlatā dasse ma sō dilatati da altri malla | cosst < r > itione (e generata dalli loro mussculi) e generata da se medjante li muscolj | dj che esso per djuerse (inc) ^obbliquita e^ concatenatione o tessuto sanza alcuna carnosita in|fra lora intermjsa (e poson) essō tali musscoli sanza alcū ujli accioche sieno attj | a stēdersi in lūgeza (a vso dj ujscio) secondo che richiede la soprabondanza del sangue | che alcuna volta achade ell panjculo esteriore che ueste tali musscoli e pelliculoso carnoso | e molto djlatabile – | The upper ventricles of the heart [atria] do not dilate by themselves, but they are dilated by the other ventricles. However, their contraction is generated by themselves by means of their muscles. These through their different obliquities, interlacing or interweaving, without any fleshiness intervening between them, are muscles without threads so that they are suitable for stretching lengthwise in accordance with the demands of the superabundance of blood, which sometimes occurs. And the exterior membrane that coats these muscles is membranous, fleshy and very dilatable. |

[II] se ttu djrai quessti 4 ventriculi e|ser 2 perche ognj binario mette | lū nelaltro jo djro che ttutte le | vene (elle) sien una medesima per|che lunamette nelaltra e cosi le | intestine perche me son djuisi da usciolj | che quesste – | [II] If you say that these four ventricles are two because each pair leads from one into the other, I will say that all the veins are one and the same because one leads into the other, and likewise the intestines because they are divided up by little doors likewise. |

[III] se ttu djche | li 2 ventriculj | superiori e inferi < o > |re sieno vn mede|simo (per) ancor co sol | tali ussciolj posti ne|lle lor parietj siē se|parati io djro ancora | chella camera ella | (piaza) sala sia vna mede|sima per | eser so|l sepera|te da |vna | porta|pol^a^ | [III] If you say that the two upper and lower ventricles are one and the same, although they are separated only by one such little door placed in their walls, I will further say that the chamber and the hall are one and the same because they are separated only by a small doorway. |

[IV] prova come li uētriculj superiori | nō sono vnmedesimo ventriculo | colli ventriculi inferiori – non po stare < i > numedesimo tē|po < i > nu medesimo subbietto due | moti contrari coe pentimēto | e volonta · adunque se lj uen|triculj destro superiore e infe|riore sono vn medesimo ellj | e necessario che inmedesimo | tenpo tutto fachia vn medesi|mo effecto e nō due effettj | nati da intētione rettamēte | cōtraria come far si uede | al ue$triculo desstro (col s) su|periore collo inferiore inpero|che cquādo lo inferiore si ri|strigne il superiore si djlata | a ssincorpora il sangue (da lluj | scacca) che da esso ventricu|lo inferiore fu scaccato e | simjlmēte fa iluentriculo | superiore quando refrette il | sangue (ricievuto che) a chi | conquello lopercosse aiutando | ilnatural refresso col suo | risstrignjmēto quella qual|cosa il moto si fa piu velo|ce nel refrusso del sāgue | nelritornare nel uētricu|lo del core donde (f) prima | fu sospinto – | [IV] Prove how the upper ventricles are not one and the same ventricle with the lower ventricle At one and the same time in one and the same cause two contrary movements cannot exist, that is repentance and desire. Therefore if the right upper and lower ventricles are one and the same it is necessary that at the same time the whole should produce one and the same effect and not two effects arising from directly contrary tendencies as one sees produced by the right upper ventricle with the lower, since when the lower one contracts the upper one dilates and incorporates the blood which has been driven out of the lower ventricle. And the upper ventricle does likewise when it reflects the blood back to that ventricle from which it was percussed, helping the natural reflection with its contraction. This movement of the reflection of the blood is made somewhat more swiftly in its return into the ventricle of the heart from which it was first pushed out. |

E ilmedesimo balzo fa nel | ricadere delcore creato da|linpeto delmoto che percote | il fondo dello inferiore vē|triculo donde nel tenpo che | ess < o > risalta daesso fondo il | core sirestrigne e avmēta | il moto che fa ilsangue alla|ltra percusjone delcoperchio | delsuperiore uētriculo E ss|e tu djrai che magior percussio|ne sia quella che da il sangue | che djscēde alfondo dello inferior | vētrichulo che cquel che percote | ilcoperchio deluētriculo superio|re perche lū moto e naturale ellal|tro no qui sirisponde che ljqujdo | nelliqujdo non pesa [:–:] se non quan|te la per|cussio|ne che | lui ge|nera | And the same rebound is made in the falling back of the heart created by the impetus of the movement which percusses the bottom of the lower ventricle from which, during the time that it leaps back from this base the lower ventricle is greater than that which percussed the cover of the upper ventricle because the one movement is natural and the other is not, here one replies that liquid is weightless in liquid [:–:] except by the amount which percussion generates. |

[V] volta | carta | [V] Turn the page. |

RL 19063 verso, Notes on the action of the heart, etc. Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci 1452-Amboise 1519). c.1511–13. Pen and ink (Lent by Her Majesty The Queen. Royal Collection © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II)