(1)

Department of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery, Papworth Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, Cambridge, UK

Abstract

Leonardo’s heart studies from the years about 1513 to 1514 represent the pinnacle of his anatomical endeavours. They integrate structural form and dynamic function in a way that called upon his extensive experience and knowledge of hydrology, engineering, mathematics, and architectural design. From the evidence of the existing notes, he entered this period of study of the heart with a Galenic perspective of the movement of the blood. It is clear from the rhetorical nature of his commentary, however, that the only way that he could satisfy his desire to truly and accurately understand the detailed function of this complex organ was by using dynamic laws, and although there is no extant record of it, acknowledging the importance of mathematical proof wherever possible. This inquisitive and original approach inevitably brought him into territory that would conflict with Galen’s concepts of the ebb and flow of the blood. Whilst Leonardo’s extant notes fall short of a direct challenge to Galen’s postulates, there are sections that clearly suggest different explanations. A good example of this is his conclusion that the air passages are not directly connected to the blood vessels in the lung, as had been suggested by Galen, and indeed by Erasistratus (304–250 B.C.E.) before him. Galen’s hypothesis explained how the vital spirits contained within the inhaled “pneuma” or air, could enter the heart. Leonardo carried out an experiment in which he inflated a pair of excised lungs and then tied off the principal airway (the trachea). In doing so, he found that there was no leakage of air from the lungs, thereby disproving Galen’s hypothesis. As far as we know, Leonardo did not offer an alternative solution to the transference of life-giving forces.

Admirable instrument, invented by the Supreme Master

Leonardo’s heart studies from the years about 1513 to 1514 represent the pinnacle of his anatomical endeavours. They integrate structural form and dynamic function in a way that called upon his extensive experience and knowledge of hydrology, engineering, mathematics, and architectural design. From the evidence of the existing notes, he entered this period of study of the heart with a Galenic perspective of the movement of the blood. It is clear from the rhetorical nature of his commentary, however, that the only way that he could satisfy his desire to truly and accurately understand the detailed function of this complex organ was by using dynamic laws, and although there is no extant record of it, acknowledging the importance of mathematical proof wherever possible.1 This inquisitive and original approach inevitably brought him into territory that would conflict with Galen’s concepts of the ebb and flow of the blood. Whilst Leonardo’s extant notes fall short of a direct challenge to Galen’s postulates, there are sections that clearly suggest different explanations. A good example of this is his conclusion that the air passages are not directly connected to the blood vessels in the lung, as had been suggested by Galen, and indeed by Erasistratus (304–250 B.C.E.) before him.2 Galen’s hypothesis explained how the vital spirits contained within the inhaled “pneuma” or air, could enter the heart. Leonardo carried out an experiment in which he inflated a pair of excised lungs and then tied off the principal airway (the trachea). In doing so, he found that there was no leakage of air from the lungs, thereby disproving Galen’s hypothesis.3 As far as we know, Leonardo did not offer an alternative solution to the transference of life-giving forces.

The dynamic nature of heart action and the ever-changing demands on its output and power make it an organ that can be understood only by integrating form with function at every level. This is the approach that Leonardo used in his descriptions of cardiac function. Even in the current era of advanced molecular biology, mathematics, and engineering, we struggle to fully decipher the complexities of the normal and diseased heart. Indeed, in the past 30 years the worldwide expenditure on cardiac research has been vast, and it continues to grow as the answer to each question throws up many new lines of enquiry.

Modern cardiologic investigation requires highly sophisticated techniques of dynamic imaging and measurement, all underpinned with sound experimental modelling and mathematical proof—a process of information gathering in the mould of Leonardo’s ground-breaking studies. I hope to help the reader to appreciate the profound nature of some of Leonardo’s observations and deductions by explaining the current understanding of some aspects of cardiac function and by using modern imaging technology wherever possible to illustrate some of his novel observations.

Whilst trying to elucidate the nature of his genius in this highly specialised subject, I have found that his use of rhetorical reasoning and purity of observation encourages an ability to see old problems in new ways. Indeed, concepts that he explored in depth, such as the nature of the flow of blood through the heart (as exemplified by his study of the vortices in the aortic root), have been largely neglected until the present day. Only now, with the advent of accessible technology such as advanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), are enquiries such as these being reinvigorated.

In the Quattrocento, scientific enquiry, as we understand it, hardly existed, but some of Leonardo’s methods were of ground-breaking scientific nature. They arose from his unusually questioning mind, allied to a use of classical disciplines. In particular, he believed in the power of the forces of nature that caused everything to be in the form that it is for reasons that, once understood, would lead the enquirer to their full understanding. His imagination resulted in much cross-fertilisation of ideas. One can clearly see his experience in one discipline informing his understanding of others. This is particularly obvious in his studies of the valves of the heart, which utilised his extensive knowledge as a hydrodynamic engineer and his fascination with geometry, amongst other things.

The structure of the heart can be understood only by investigating the way in which it works. In the case of such an organ, the investigator must rapidly move on from simple observation and recording of the static anatomy into the dynamic function. This requirement was clearly appreciated by Leonardo. Although the cardiac notes are rich in images, they reveal a lot of thinking on paper through the use of many words. Leonardo stressed the dominance of the visual image for demonstrating structure, but he also accepted the need for words to satisfactorily explain function (physiology). Hence the density of text found on the pages of notes that address the heart.

In the time of Leonardo, two of the great challenges of natural philosophy (biological science today) were attempts to understand the way in which a new life is formed and then to explain its subsequent sustenance and growth. Any explanation of the growth of a newly formed life and its healthy existence until death requires an understanding of the access of all of the body’s tissues to nutrition and the “vital spirits”, inevitably leading to the need to understand how these vital forces are captured and distributed—and hence to the function of the heart, lungs, and intestines. Perhaps it should come as no surprise that the enquiring mind of Leonardo should engage in these challenges towards the end of his academic life. By that time, he had engaged in all of the necessary academic disciplines and he was uniquely placed to make new and exciting discoveries. Perhaps he had also accomplished all that he wanted to do in understanding the musculoskeletal aspects of the human body.

As we shall see, Leonardo had made considerable strides in the knowledge of the structure and the function of some of the subsystems of the heart; through a failure to publish, these were not turned into a significant and recognised contribution. Several of his ideas continue to sit well alongside our modern understanding of cardiac physiology, and some presage today’s cutting-edge functional hypotheses. In judging his work, and in particular in judging its perceived deficits, it must be remembered that his pages on the heart represent a tiny fraction of his manuscripts that are still in existence, and their fragmentary nature suggests significant losses over the intervening years. The fragmentary nature of the extant notes makes it difficult to find an order to his work. Some parts have a degree of cohesion, perhaps following his preparation for publication. Some subjects are more finished than others, and some appear under headings; for example, RL19078 verso has at its head “Geography of the heart” and RL19074 recto is headed “Of the valves of the heart”.

In an attempt to bring some kind of order to the work whilst respecting Leonardo’s approach, I have arranged the sections in the following way: First, I have included a general description of the working heart, to enable readers who lack an anatomical or medical background to gain some insight into the specialist knowledge that might be assumed. The next section gives some general comments on the muscular nature of the heart, followed by the external appearance of the heart. We will then journey through the interstices of the heart, grouping together the internal subsystems following Leonardo’s descriptions. Finally, I will attempt to put all of this work into the context of the movement of the blood as realised by Leonardo, and will conclude with a review of some of his references to the diseased heart.

The Normal Working Heart

The heart is a powerful example of the nature of evolutionary development. The progress of life forms from single-celled structures to multiple-organ individuals demands the emergence of a system to supply nutrition and remove effluent from all parts of the body. For the first days of human embryonic development, whilst embedded in the wall of the mother’s uterus, oxygen and nutrients can reach all of the cells by simple diffusion from areas of high concentration to those of low concentration (along concentration gradients). Soon, however, the embryo reaches a size that requires a formal circulation, as the distances across which diffusion would be necessary become too great. Capillary networks form, through which the vital nutrients can reach the rapidly dividing cells. From the fourth to the sixth week of development, a group of cells form into a tube, which begins to differentiate into the chambers of the heart, beginning with the atria.4 These cells possess the special property of contractility, and from a very early stage, cells can be seen to contract with a spiral wave beginning at the atrial end, in an action that resembles the wringing out of a towel. Interestingly, before the arteries and veins link together through the capillary networks, the first flow of blood within this tubular system is Galenic, with an ebb and flow pattern. It is only as the foetus grows and the capillary connections form that the formal circulation begins. As the tube of muscle cells grows, it twists and rotates in an extremely complex way, eventually establishing the relationships that we recognise in the adult heart.

The fully formed heart consists of four chambers arranged in two pairs. There are two weakly contractile receiving chambers called atria (from the Latin atrium, which means a hallway) and two powerful pumping chambers called ventricles. They are connected in series and they communicate through one-way, non-return valves. Between the right atrium and right ventricle is the tricuspid valve, and between the left atrium and left ventricle is the mitral valve. These valves allow blood to pass from the atria into the ventricles but oppose return flow into the atria. Similarly, two unidirectional valves control the outflow from the ventricles. The pulmonary valve prevents reflux of blood in the outflow from the right ventricle to the lungs, and the aortic valve performs the same function in the outflow from the left ventricle to the rest of the body.

The pairs of chambers are described as being either right or left. The concept of sidedness of the heart relates to their relationship to the lungs and not to their mature position within the chest. In the natural state within the body, the right atrium and right ventricle lie as much on the front of the heart as they do on the right side. The left atrium and ventricle are more towards the back of the chest than they are to the left side.

Blood leaves the right side of the heart to enter the lungs, from which it returns to the left-sided chambers, before departing for the rest of the body. Blood returning via the great veins from the many organs of the body to the right side of the heart is low in oxygen content and high in carbon dioxide. The reverse is true of the blood that returns to the left side of the heart from the lungs. The passage of blood through the lungs removes carbon dioxide and enriches it with oxygen.

A general rule states that arteries always carry blood away from the heart, and veins towards the heart. With the exception of the pulmonary artery, all arteries contain oxygenated blood. The pulmonary artery, which leaves the heart to carry blood to the lungs, carries the deoxygenated blood that has returned from the tissues of the body. Similarly, all veins other than the pulmonary vein contain blood rich in carbon dioxide.

Arteries branch like the branches of a tree, and veins receive tributaries, as does a major river. As we shall see, the cross-sectional area of the parent vessel is equal to the sum of the cross-sectional areas of its branches. Leonardo defined this relationship as a natural law.

All of the structures of the heart exist to provide the impetus, direction, and rhythmic flow of the blood. Therefore I will describe the structures of the heart in the order that the blood flowing through it will encounter them. Blood returns from the head and upper body via converging tributaries of veins that culminate in one large vein, the superior vena cava (SVC). This expands to form the upper part of the right atrium. Blood returning from the lower body via a myriad of converging venous tributaries enters another large venous channel called the inferior vena cava (IVC). The IVC then enters the inferior part of the right atrium. This chamber is in two parts: The first is formed by the confluence of the superior and inferior vena cavae; it has a smooth internal lining and thus is called the sinus venosus part. The rest of the right atrium is formed as part of the heart tube and has a lining that is elevated in a mass of interwoven bars of muscle called trabeculae. This is where the true heart muscle begins. The junction between these two areas forms a ridge called the crista terminalis (terminal crest).

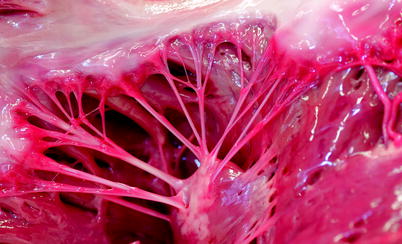

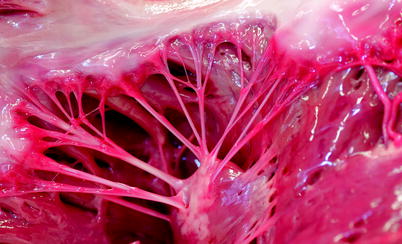

The blood then flows across the first of the atrioventricular valves within the heart, the tricuspid valve. This valve has a complicated relationship with the right ventricular muscle below. Fine, tendinous cords (which look rather like the strings on a parachute connecting the sheet to the person suspended below) connect the tricuspid valve to outcrops of muscle in the ventricle, called papillary muscles (Fig. 4.1). This valve, as with the other three valves, opens and closes under the force and direction of the flowing blood in response to the cyclical contraction and relaxation of the heart muscle. Other influences, such as vortex formation in the flowing blood, play an important part in the closure of the valves in such a way that no backward leakage of blood can occur. As we shall see, this idea was one of Leonardo’s most accomplished pieces of work, not appreciated until the twentieth century.

Fig. 4.1

Photo of a tricuspid valve. The chordae can be seen arising from the papillary muscles, reaching up to the leaflet of the valve. This arrangement in the mitral valve is very similar

When the ventricle is nearly full, the right atrium contracts to send the final portion of blood into the ventricle, whose cavity is then stretched open even further. Heart muscle has an elastic component, and this final stretch imparts extra energy to the ventricle. This elasticity was also recognised by Leonardo in relationship to the normal function of the aortic valve and root. The elastic recoil then powers the beginning of the ventricular contraction phase, which drives some of the blood up against the tricuspid valve, forcing it to close. The remainder of the blood forces open the pulmonary valve and flows onwards to the lungs. Whilst the ventricle is contracting and thereby emptying, blood continues to return to the atrium, filling it so that it is ready for the next phase of ventricular filling.

The main pulmonary artery divides into two, one part for each lung. These then divide again and again as the branches pass into the depths of the lung tissue. At their terminations, they become very small and are termed arterioles. At their ends, they merge into the capillaries. The capillaries are tubes that are only a single cell thick, forming a very weak barrier across which gas and nutrition can easily diffuse into the surrounding tissues.

The red cells of the blood pass through the fine capillary network of the lungs. They contain complex molecules called haemoglobin, whose special property is to loosely bind molecules of oxygen to themselves. Thus oxygen is carried onward to the tissues of the rest of the body. Oxygen is the active ingredient of the mystical vital spirit “pneuma”. The transfer of oxygen, carbon dioxide, and the nutritious elements of the blood is passive. That is, the transfer occurs with the expenditure of minimal energy, along concentration gradients. In other words, the blood entering the lungs has given up a lot of its oxygen and is entering an environment where the oxygen concentration is high. Oxygen molecules therefore move from the lung air spaces into the blood. The reverse is true for carbon dioxide.

At the end of the capillary networks, the tiny vessels coalesce to form small veins (venules), which themselves coalesce into the larger veins, and ultimately these all merge into the pulmonary veins, which leave the lungs and enter the left atrium of the heart. There are two pairs of pulmonary veins (one pair from each lung), which enter either side of the left atrium. From the left atrium, blood then flows across the second atrioventricular valve, the mitral valve, located at the mouth of the left ventricle, the powerhouse of the systemic circulation. When this ventricle contracts, the blood is ejected under high pressure out through the aortic valve and onwards throughout the body via the aorta. The contraction of the left ventricle simultaneously causes the mitral valve to close.

The closure mechanism of the aortic and pulmonary valves is sophisticated and involves complex hydrodynamics that were first described by Leonardo. We will explore this discovery in detail later.

The contraction of the chambers of the heart is instigated by nerve impulses, which arise first in a specialised group of heart cells collectively called the sinoatrial node. Found at the junction between the superior vena cava and the right atrium, this is a concentration of electrically active cells that fire together at a rate that is controlled by the demands of the level of exercise or stress of the individual; increased demands for oxygen and energy cause chemicals in the blood to change, making the cells fire more rapidly. The nerve impulses then flow throughout the atrial muscle, causing a wave of contraction. They then coalesce at another clump of specialised heart muscle cells called the atrioventricular node. This lies in the crest of the septum (the dividing wall) between the two ventricles. The electrical wave then spreads throughout the two ventricles, causing them to contract. The two atria and the two ventricles contract together and in sequence, atrial contraction preceding contraction of the ventricles. As the atria contract at the end of the ventricular filling phase, the ventricles are relaxed. When the ventricular filling phase is ended, the ventricles contract, and at this time the atria relax to refill. The phase of ventricular contraction in the cardiac cycle is referred to as systole and the phase of relaxation as diastole. As we shall see, Leonardo commented upon the neuromuscular activity of the heart.

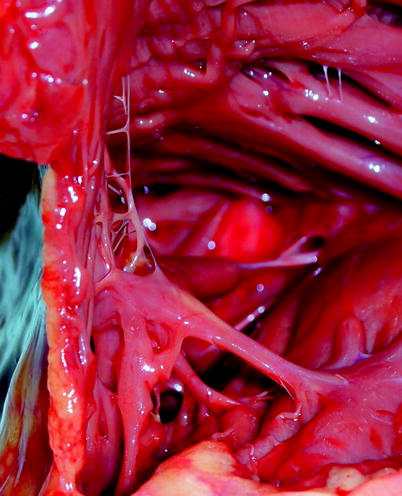

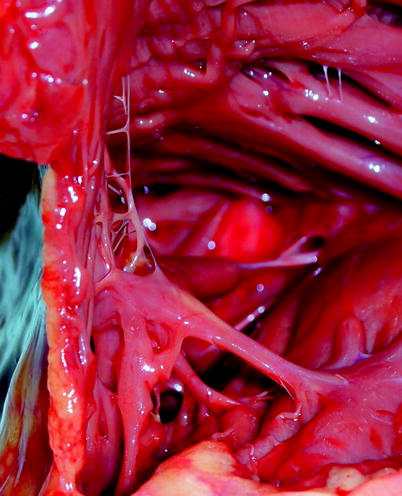

The internal structures of the heart are complex both in their overall form and in their content. The right ventricle operates under lower pressures than the left, and consequently it has a thinner muscular wall. Its external wall is relatively unsupported, and as a result in some animal species it has a muscular bar stretching from the internal (septal) wall to the external wall. This is the structure first recorded and named by Leonardo as the “moderator band.” Its presence prevents over-distension of the thin ventricular free wall (Fig. 4.2). The internal aspect of the ventricular walls is characterised by the protrusion of muscular bands, which form many nooks and crannies between them. These protrusions coalesce into large muscular projections called papillary muscles. From these arise the tendinous cords that support the ventricular side of the tricuspid and mitral valves. These cords are arranged in three layers, referred to as primary, secondary, and tertiary cords. The primary cords insert into the leading edges of the leaflets and act as guy ropes bringing the leaflet edges into line as they close in systole. The secondary cords, which are sturdier, reach up to the underside of the valve, where they fan out to spread like the fan vaulting of a church roof (Fig. 4.3). This arrangement allows allow the load placed upon them at maximum pressure of the ventricular contraction to be equally dissipated. The third group of tendinous cords, the tertiary cords, extend to the base of the valve just next to its origin from the ventricular wall. These cords are under tension throughout the cardiac cycle and act like “tie-rods” in an engineering sense, supporting the ventricular wall. These architectural relationships are important for the normal functioning of the ventricles. If it is not respected and preserved during valve replacement surgery, the heart will progressively distort from its normal conical shape to a sphere. This altered geometry causes the heart to fail over a number of years. An example of this type of cord is drawn by Leonardo, but without commentary.

Fig. 4.2

Photograph of the moderator band in a human heart. Although quite well developed in this example, it is often very indistinct

Fig. 4.3

Photograph of the underside (ventricular surface) of the mitral valve. The leaflet is being drawn up to show the arcades of chordae tendinae

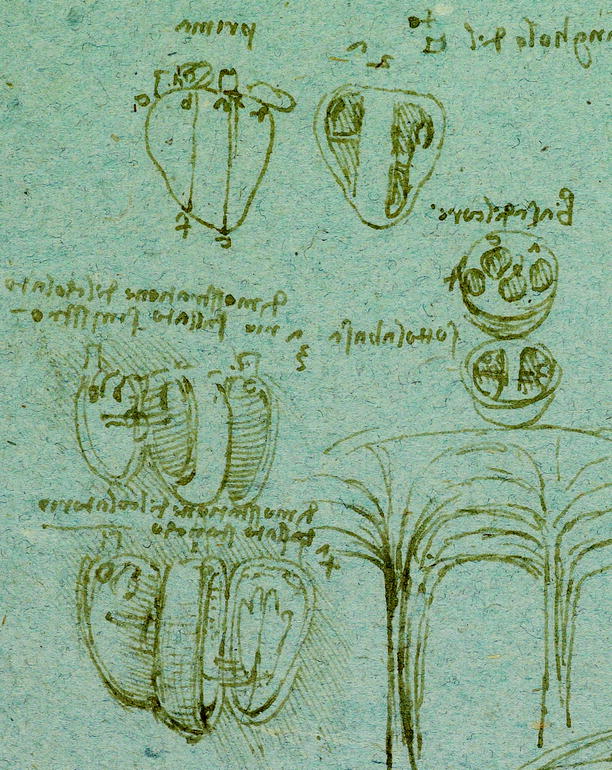

The two arterial valves, pulmonary and aortic, are made up of three semilunar leaflets (so called because of their resemblance to a half moon). These “lunules” (valve leaflets) must support each other at their closure line, as no tendinous cords are attached to them (Fig. 4.4). They close under a lower pressure than the tricuspid and mitral valves, which must close in the powerful contraction phase of the ventricles as they generate their maximal pressure. The left ventricle generates a much higher pressure than the right ventricle, and thus the mitral valve has to close under the highest pressure of all of the valves.

Fig. 4.4

Photograph of human aortic leaflets

The heart has its own blood supply. This is delivered to the heart by two main coronary arteries, the right and the left. They are the first branches of the aorta (the large artery that leaves the left side of the heart to supply blood to the whole body other than the lungs). The coronary arteries arise from hemispherical expansions in the root of the aorta, (the sinuses of Valsalva), which begin immediately above the leaflets of the aortic valve.5 The coronary arteries give their names to the particular aortic sinuses from which they arise. Hence, there is a right, a left, and a noncoronary sinus. The latter (as its name implies) is the sinus of the aorta, which does not give rise to a coronary artery. As the blood exiting the ventricle enters the sinuses, vortices form within them as the blood is channelled back upon itself towards the upper side of the base of the leaflets. This motion begins to make the semilunar leaflets drift towards each other, initiating the first phase of valve closure. It also drives blood into the coronary arteries, enhancing perfusion of the heart.

The coronary arteries divide repeatedly and delve down into the heart muscle, providing its nourishment. Maximum flow in these vessels occurs during the relaxation phase of the cardiac cycle. Blood returns from the heart muscle via venous tributaries to enter the large vein, the coronary sinus, which ultimately flows back into the right atrium of the heart.

All of the structures of the heart are forged by the dynamic function that they are called upon to carry out. Therefore a teleological approach to their understanding is a laudable way to proceed. Thus Leonardo’s method of using the observed effect to define its cause yielded fascinating results. In his own words: “O marvellous necessity, thou with supreme reason constrainest all effects to be the direct result of their causes, and by a supreme and irrevocable law every natural action obeys thee by the shortest possible process”.6

Leonardo’s Methodology

Before we consider in detail Leonardo’s research of the heart, it is important for us to recognise the novel methods that he devised to enable him to reach his conclusions. Leonardo took the natural world and man’s experience of it as his touchstone for truth. He wrote, “Experience, interpreter between formative nature and the human species, teaches that, that which this nature works among mortals, constrained by necessity, cannot operate in any other way than that in which reason, which is its rudder, teaches it to work”.7

His method consisted of extracting “experiences” by close scrutiny of the effects of phenomena from the greater world around him and distilling from them the questions of causation that he wanted to answer. These questions were then turned into the first examples of “experimentation” within a controlled environment. This personal experiential philosophy he described thus:

First I shall test by experiment before I proceed farther, because my intention is to consult experience first and then with reasoning show why such experience is bound to operate in such a way. And this is the true rule by which those who analyse the effects of nature must proceed: and although nature begins with the cause and ends with the experience, we must follow the opposite course, namely begin with the experience, and by means of it investigate the cause.8

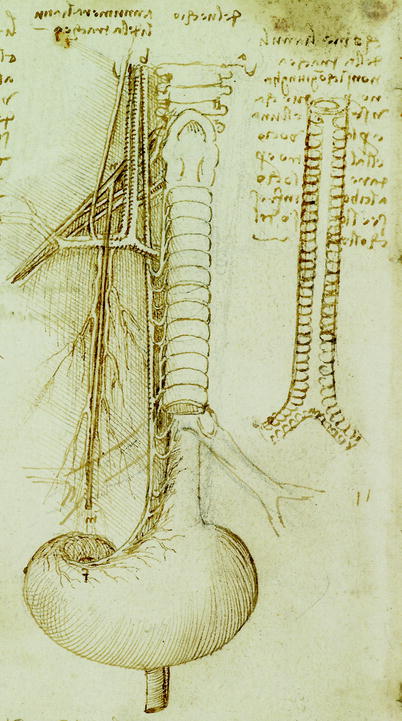

Seeing bodily organs in their functioning state, as if in life, was a sine qua non for Leonardo. Nature made everything in the form that it did for a specific purpose (“In nature there is no effect without cause….”9), so it must be examined in a state as close to its natural form as possible. Leonardo abhorred vivisection and therefore denied himself the easier route of observing the heart in its normal working state. Instead, he developed methods of demonstrating the chambers of the heart and the ventricles of the brain in their normal distended state by injecting them with wax. In the case of the brain, it was simple to remove the outer brain to reveal the solidified wax, which had then taken the form of the internal ventricles.10 Comparison of Leonardo’s images with those of an actual cast reveal the accuracy of his work (Figs. 4.5 and 4.6). Undoubtedly these are methods borrowed from his knowledge of both sculpture and engineering, and have reference to the lost wax method of casting.

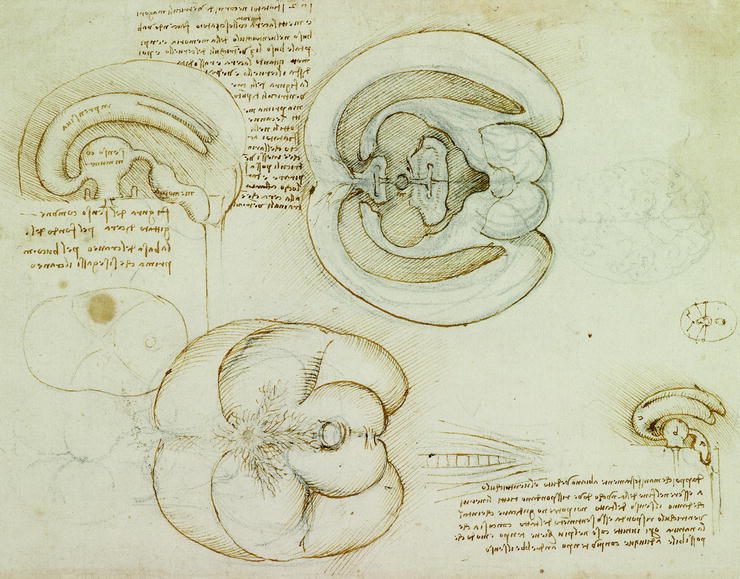

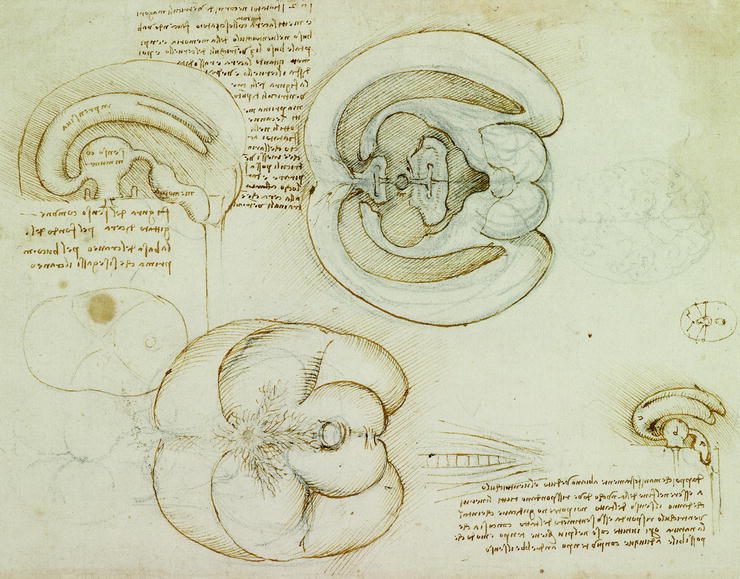

Fig. 4.5

Drawing to show the cerebral ventricles. RL 19127 recto, The brain. Leonardo da Vinci. c.1508-9. Pen and ink over black chalk (Lent by Her Majesty The Queen. Royal Collection © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II)

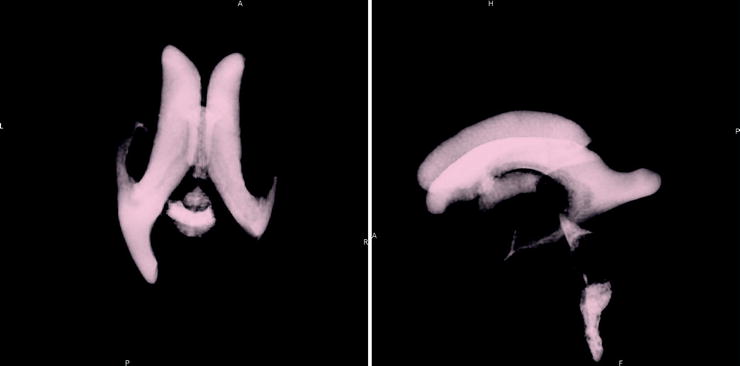

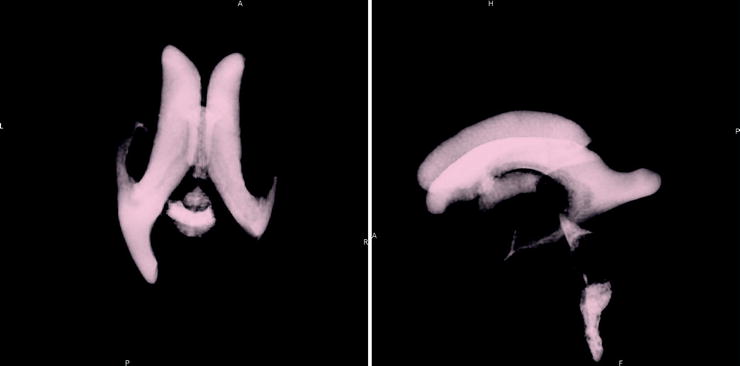

Fig. 4.6

(a, b) Modern images of the cerebral ventricles. Casts of the cerebral ventricles can be made by injecting hot liquid wax or silicone into them and then removing the brain tissue once the wax or silicone has set, revealing a cast of the ventricles. These can then be photographed and stored for teaching purposes. These days it is possible to render the shapes with CT or MR scanning and subtracting the data from around them, revealing their true shape, which can then be digitally imaged alone

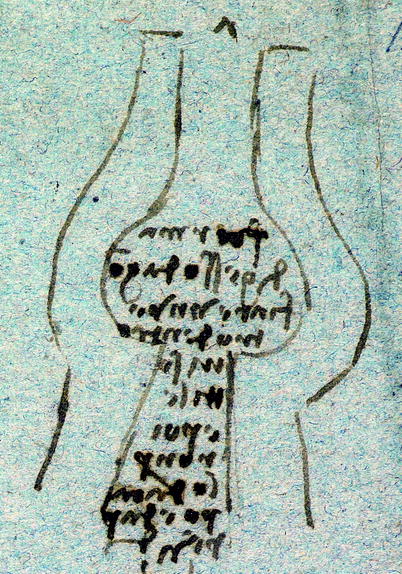

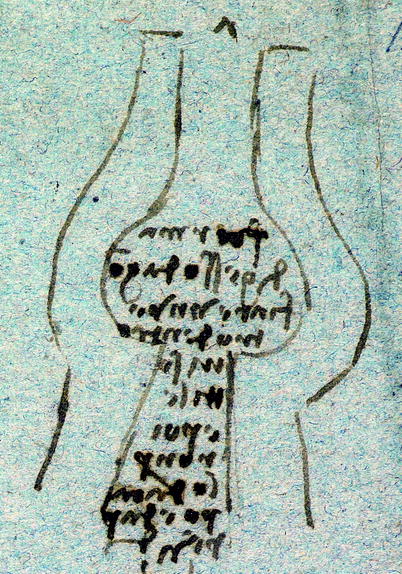

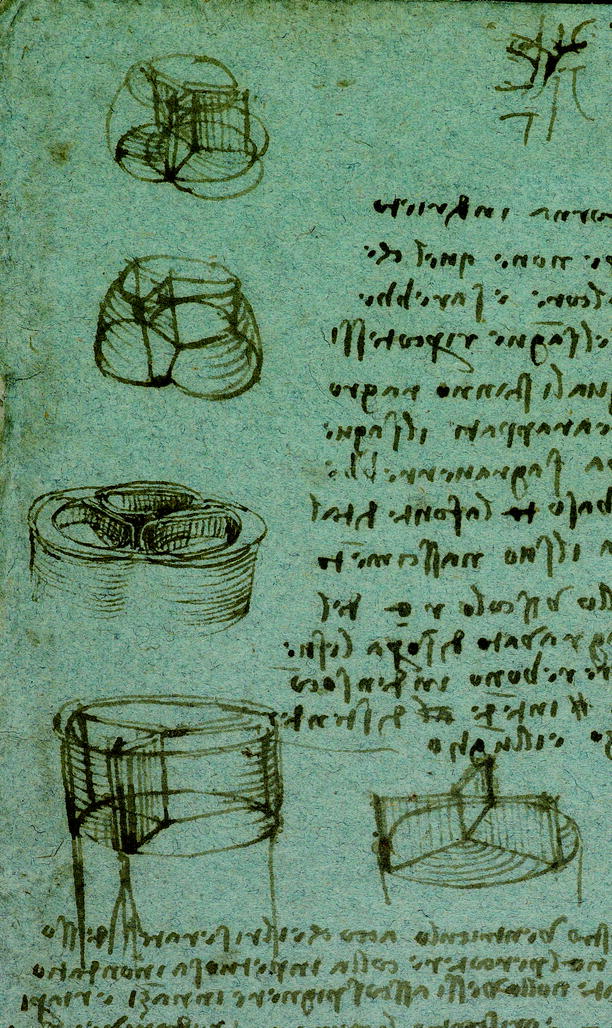

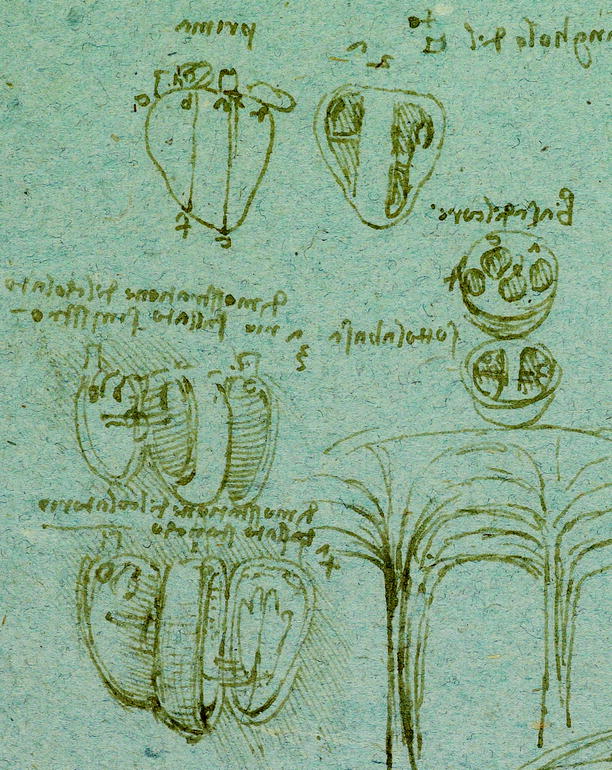

In his work on the understanding of the aortic valve and the outflow from the left ventricle of the heart, Leonardo described a method of constructing a glass model in which to demonstrate the complex flow of blood through this channel. Here he also used the molten wax injection technique. He wrote, “A plaster mould to be blown with thin glass inside and then break it (the mould) from head to foot at ‘a n’. But first pour wax into this valve of a bull’s heart so that you may see the true shape of this valve” (Fig. 4.7).

Fig. 4.7

The proposed plaster mould. Detail from RL 19082 recto, The aortic valve. Leonardo da Vinci. c. 1512–13. Pen and ink on blue paper (Lent by Her Majesty The Queen. Royal Collection © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II)

A similar technique is used today by some valve manufacturing companies when modelling designs for replacement valves. Modern technology uses silicone rather than wax, as it is stable at higher temperatures than wax, making it easier to work with (Fig. 4.8).

Fig. 4.8

A silicone mould of the aortic root of a pig. This gives a negative cast of the aortic root (in other words, the form of the blood within it). From this type of mould, Leonardo could deduce the tensioned shape of the structure (Photograph courtesy of Medtronic)

Some authors (e.g., O’Malley and Saunders) have expressed doubt over whether Leonardo actually made and used this proposed model.11 When they wrote, in 1952, no one had properly investigated the problem of how the aortic and pulmonary arteries actually worked. There was no published description of the true mechanism in the medical or scientific literature. Therefore those authors could not have known of the accuracy of Leonardo’s work nor of the complexity that was entailed in its demonstration. Indeed, the first scientific examination of the problem that is reported in the literature is a paper by B. J. Bellhouse and F. H. Bellhouse from the Department of Engineering Science in Oxford University, which was published as a communication in Nature in 1968.12 The only reference it contains is to Kenneth Keele’s publication13 describing Leonardo’s original work, which of course was never published by its original author.

The work was further highlighted in an article by Professors Gharib, Kemp, and others, in which they further amplify the accuracy of the original observations14 (Fig. 4.9). Professor Kemp retains a healthy scepticism with regard to whether Leonardo really proved his hypothesis with the use of the model.15 He asks whether the model would have been sophisticated enough, even with the seeds dispersed within it, to visually demonstrate the detail that Leonardo reveals in his multiple drawings. I suspect that Leonardo’s knowledge of hydrodynamics and his powerful deductive reasoning would have made him convinced in his own mind that his hypothesis was correct. Even the most subtle confirmation of his prior deductions in the model would have been enough to affirm his thoughts, although I suspect that having had the idea, he would have wanted to see it through. After all, the model was not complex to make, and the hard work had been done in the development of the idea. Although he deduced the expected findings from his other hydrodynamic work, his drawings of his final solution are so compelling as to suggest that he witnessed it. The reality is so complex that it was only been proven beyond doubt in the second half of the twentieth century and was only demonstrated in the live, working human heart as recently as the past few years.

Fig. 4.9

(a, b) Gharib and Kemp’s model of the aortic flow experiment (Photographs courtesy of Professor Morteza Gharib, Professor of Bioinspired Engineering, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, California, USA)

In his descriptions of the morphology of the internal aspects of the auricles (atria) of the heart, Leonardo describes yet another method by which he was able to estimate the volume of the chamber: “Before you open the heart inflate the auricles of the heart beginning from the aorta. Then tie it off and examine its volume. Then do likewise to the right ventricle or right auricle. Thus you will see its shape and its function.”

In trying to understand the mechanism of the aortic valve, Leonardo becomes a truly modern scientist. As with all good science, he identified the correct questions to ask from closely studying the shape of the distended aortic root of the bull’s heart, and he then set about reconstructing the complex geometry and its relationship to the valve leaflets by designing the circuit in which to place the glass model of the aortic root. He went further by drawing, and probably making, his own form of a trileaflet valve with semilunar leaflets, accurately reproducing the natural valve complex (Fig. 4.10). This piece of work antedates modern synthetic valve design.

Fig. 4.10

Leonardo’s drawings of the proposed design for the aortic/pulmonary valve. Detail from RL 19082 recto, The aortic valve. Leonardo da Vinci. c.1512–13. Pen and ink on blue paper (Lent by Her Majesty The Queen. Royal Collection © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II)

Thus, when Leonardo freed himself of the pre-existing concepts of his time and became immersed in concentrated analysis of his anatomical observations, he was at his most inventive. His resolution of problems remains apposite and accurate even through the perspective of modern knowledge. Indeed, his creativity in thinking through problems is at times quite breathtaking.

Accurate dissection manuals now guide the student of anatomy in the right direction, but of course in Leonardo’s time there were no such manuals. He had to determine how to open the heart to optimise the view of the internal structures. In a geometric sense, the normal heart is a complex cone—that is, a cone with a twist. This twist distorts the internal architecture around the spiral, so that the number of cuts to be able to see the majority of the internal structures is limited. Leonardo appears to have worked out this problem and displays his incision lines in his drawings (Fig. 4.11). Contemporary cardiac pathologists inform me that Leonardo’s chosen incisions are correct and similar to those used today16 (Fig. 4.12).

Fig. 4.11

Diagram of the incisions that Leonardo used in some of his dissection of the heart. Detail from RL 19080 recto. The left ventricle and mitral valve. Leonardo da Vinci. c.1512–13. Pen and ink on blue paper (Lent by Her Majesty The Queen. Royal Collection © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II)

Fig. 4.12

(a) Illustration of modern incisions used to demonstrate the internal structures of the heart. The intact membrane may be seen to the best advantage by the use of the incisions demonstrated in the first drawing. The primary incision passes through the nadir of the right aortic annulus and is carried across the right ventricle between the segments A and B. These are distracted and two additional incisions are made to allow the interior of the specimen to be examined. The dotted line indicates the attachment of the chambers on the opposite side of the membrane. In the second drawing, this incision passes through the left anterior fibrous trigone and across the infundibulum of the right ventricle to the apex, whence it extends to the ostium of the left ventricle, separating the septal and posterior walls en route. The all-important ostium of the left ventricle is seen after the posterior papillary muscle is divided and then elevated. The left aortic annulus is separated 3 mm from the left ventricular ostium. This represents an extreme degree of the tendency of human hearts to demonstrate a membranous type of attachment of the aortic annuli to the ostium. The left, left anterior, and intervalvular fibrous trigones are in continuity. A heart with this type of configuration would be a prime candidate for the development of annular subvalvular left ventricular aneurysms, which are seen most often in the Bantu (From W.A. McAlpine. Heart and Coronary Arteries. (Berlin: Springer, 1975), 11). (b) Leonardo’s same incision to show the septum (the sieve). RL 19074 verso, The heart and coronary vessels. Leonardo da Vinci, c. 1511–3. Pen and ink on blue paper (Lent by Her Majesty The Queen. Royal Collection © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II). (c) Leonardo’s planes of section of the bovine heart

Leonardo’s task in trying to understand the heart was huge, but with great originality he advanced his knowledge through careful observation and experimentation. The great majority of Leonardo’s cardiac research work is based on the bull’s heart, although one drawing17 appears to represent the interior of the right ventricle of a human heart (Fig. 4.13). The most obvious differences between the hearts of oxen and humans is that ox hearts are much bigger and more conical (Fig. 4.14). Also, the atria in the two species differ in their shape and in their relationship to the ventricles.

Fig. 4.13

(a) Interior of the right ventricle of a human heart. Detail from RL 19119 verso, The ventricles, valves and papillary muscles. Leonardo da Vinci. c. 1511–13. Pen and ink (Lent by Her Majesty The Queen. Royal Collection © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II). (b) Photograph of the interior of a human heart in the same orientation as (a) (Photograph courtesy of Medtronic)

Fig. 4.14

(a) Photograph of an ox heart. (b) Photograph of a human heart

Although there are significant interspecies differences in cardiac anatomy, the principles involved in the function of both hearts remain the same. Both have the same number of chambers associated in the same way and separated by the same type of valves. Other than the presence of the moderator band in the ox, the internal components of the ventricular chambers are essentially the same, but they are arranged differently to accommodate the shape of the heart in a quadruped, where it is suspended from its base rather than sitting on the diaphragm, as in humans. Therefore it is unlikely that Leonardo’s deductions about the function of the parts suffered significantly from this choice of material for his studies. Indeed, the exaggerated proportions of some of the anatomical features found in the ox heart probably inspired observations that allowed him to draw analogies from other disciplines such as hydrodynamic engineering.

The choice of the ox heart for study was also probably stimulated by the ready availability of animal parts, unlike the regulations that surrounded the human body. Slaughterhouses, though perhaps repugnant to Leonardo, would have made access to specimens for dissection much easier.

The Centenarian

In Florence, during the winter of 1507–150818 Leonardo reported a dissection that he carried out on an old man, who shortly before he died told Leonardo that he was 100 years old. During the dissection of the heart, he discovered that the coronary arteries were diseased, and Leonardo documented the first known description of coronary artery disease. Regarding this incident, he wrote, “And this old man, a few hours before his death, told me that he was over a 100 years old and that he felt nothing wrong with his body other than weakness. And thus, while sitting on a bed in the Hospital Santa Maria Nuova in Florence, without any movement or sign of any mishap, he passed out of this life. And I made an anatomy of him to see the cause of so sweet a death.”19

In this passage, Leonardo clearly states that the reason for the dissection was to discover the cause of death. Despite this man’s very advanced age, the manner of his death clearly aroused Leonardo’s curiosity. Therefore, it appears from his description that this was perhaps more of an autopsy than an anatomical dissection. Autopsy or post mortem examination to discover a cause of death was not unusual, even at that time. A physician contemporary with Leonardo, Antonio Benivieni, recorded a series of autopsies in a manuscript entitled De abditis.20

A recently published extensive review of the records of the hospitals in Renaissance Italy has shed considerable light on the practices of those institutions at that time.21 That review reveals that although the hospital Santa Maria Nuovo was among the largest in Florence, there are no records of its having a school of anatomy. Despite Benivieni’s employment at Santa Maria Nuovo as a “house doctor” none of the dissections that he reported were carried out there. On the other hand, Leonardo’s circumstances in association with that institution may have allowed him special privileges. Over the years, he had close ties to the institution and had used it as a depository for money and goods.22 Whatever the circumstances of Leonardo’s access to post mortem material, this dissection produced important and original observations.

It is here that we find the first record of arteriosclerosis, a disease that is recognised as the commonest cause of death in the modern western world. As we shall see, Leonardo compiled the three important features of the disease, which remain true today: the increased thickness in the wall of the vessels, the decreasing luminal diameter of the vessel (worst near its origin and exaggerated at divisions), and the increasing tortuosity and the resultant increasing length of the vessel.

From his dissection, he ascribed the old man’s death to changes in the aorta and its branches (the first of which are the coronary arteries). In the continuation of the previous quote, he described the effect on the tissues supplied by these vessels: “And I made an anatomy of him in order to see the cause of so sweet a death. This I found to be a fainting away through the lack of blood to the artery which nourished the heart, and the other parts below it, which I found very dry, thin, and withered.”23

Leonardo also commented upon the ease of dissection in one so thin. He added with no reference to time or place that he had also opened a 2-year-old child. This comes as something of a surprise from a layperson at a time when dissection required specific permission and was generally permitted only in criminals.24 The note continues, “This anatomy I described very diligently and with great ease because of the absence of fat and humours which greatly hinder the recognition of the parts. The other anatomy was on a child of 2 years, in which I found everything contrary to that of the old man.”25

His line of enquiry with regard to the effect of aging on the blood vessels he lays out in the following statement: “Note whether the artery is bigger than the vein or the vein than the artery; and do the same in children, young and old, male and female, and animals of the earth, air and water.”26

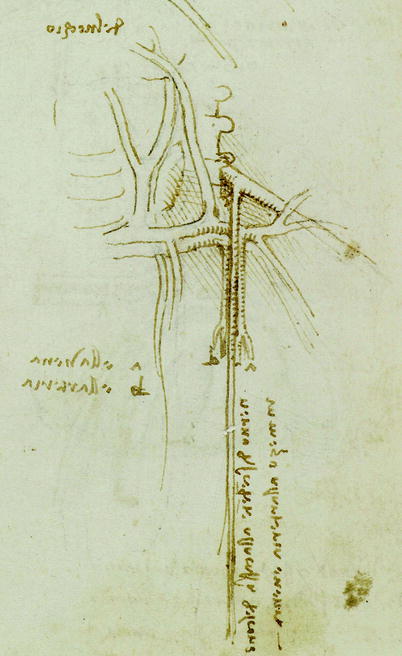

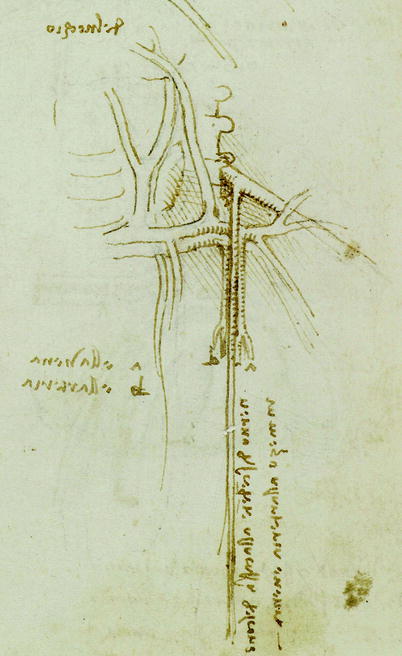

Of additional interest on this page are two sketches of the blood vessels of the left side of the neck and upper chest. Each is headed simply with the words “Of the old man”.27 They are notable for two reasons: First, they indicate the extent of dissection that Leonardo carried out on the “old man” as these structures require the removal of the anterior chest wall rather than simple opening of the chest, because of the inaccessibility of these structures as they pass behind the clavicle (collar bone) as they pass into the chest. Simply opening the centre of the chest could not reveal these areas. Second, along with the drawing on RL 19050 recto, the lower drawing of the two on RL 19050 recto is the earliest rendering of the internal mammary artery, the most important vessel used today in coronary artery bypass graft surgery (Fig. 4.15).

Fig. 4.15

Leonardo’s drawing of the internal mammary artery. Detail from RL 19051 recto, The Vessels and Nerves of the Neck. Leonardo da Vinci. c.1508. Pen and ink (Lent by Her Majesty The Queen. Royal Collection © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II)

Evidence of Leonardo’s natural use of comparative anatomy appears more than once in this work. Next to a significant drawing of the veins of the arm on RL 19027 recto is a good example, consisting of two small drawings of an artery, one of an old man and the other of a youth, both labelled as such (Fig. 4.16).

Fig. 4.16

The arteries of the old and the young, demonstrating the tortuosity that comes with old age. Detail from RL 19027 recto, The veins of the arm. Leonardo da Vinci. Pen and ink over traces of black chalk (Lent by Her Majesty The Queen. Royal Collection © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II)

It is from this comparative work on the child and the old man that Leonardo discovered the fact that aging brings about an increase in the length of vessels, and along with that an increasing tortuosity: “I also found in a decrepit old man the mesenteric veins [the vessels to the bowel], obstructing the passage of blood and doubled in length.”28 The only accompanying drawing on this page of extensive notes is a very small one that illustrates the tortuosity of vessels that arise from the abdominal aorta and supply the upper small bowel, liver, and spleen of the old man (Fig. 4.17). A similar but clearer illustration of the same part is to be found on RL 19028 verso (Fig. 4.18).

Fig. 4.17

A drawing illustrating the tortuosity of the abdominal vessels that can occur with age. Detail from RL 19027 verso, Notes on the death of a centenarian. Leonardo da Vinci, c. 1508. Pen and ink over traces of black chalk (Lent by Her Majesty The Queen. Royal Collection © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II)

Fig. 4.18

The tortuous abdominal vessels in old age. Detail from RL 19028 verso, The vessels of liver, spleen and kidneys. Leonardo da Vinci, c. 1508. Pen and ink over black chalk (Lent by Her Majesty The Queen. Royal Collection © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II)

Leonardo describes the effect of aging on the thickness of the blood vessel walls in the following fashion: “The old who live in good health die through lack of nourishment. And this occurs because the passage of the mesenteric veins [those that drain the bowel and liver] is continually constricted by the thickening of the coats of these veins [arteries?], which are the first to be completely closed.”29

It is likely that Leonardo is here referring to the arteries, as the same change does not occur in the veins of this or any other region. The narrowing of arteries to the heart, brain, and bowel often proceeds hand in hand. An infrequent but well recognised cause of serious problems and even death in some patients undergoing coronary artery surgery is death of parts of the bowel as a result of reduced blood flow through the narrowed vessels.

In trying to find an explanation for the increasing thickness of vessels (worst near to their origin) and their tortuosity, Leonardo offers the following explanation:

One asks why the veins in the aged acquire great length and those which were formerly straight become folded and their covering becomes so thick that they occlude and prevent the motion of the blood. From this arises the death of the old without disease.

I judge that a structure that is nearer grows the more; and for this reason these veins being the sheath for the blood which nourishes the body, it nourishes the veins in proportion to their proximity to the blood.30

This observation is correct, as it is the earlier branches of the arteries that develop narrowing in the region of their branching. Then drawing on a natural analogy, Leonardo reasoned that the cause of death was narrowed and hardened arteries, not the blood thickening with age, as it is continuously destroyed and then replenished. In fact, the red cells in the blood have a life of only 40 days, or just over 1 month, and the white cells, even less. His deduction is astonishing as there was no way of verifying this with certainty: “And this coat on the vessels acts in man as it does in oranges, in which, in which as the peel thickens so the pulp diminishes the older they become. And if you say that it is the thickened blood which does not flow through the vessels, this is not true, because blood does not thicken in the vessel since it continually dies and is renewed.”31

In describing the results of these changes, Leonardo wrote, “Vessels which [in the elderly] through the thickening of their tunics restrict the transit of the blood and, owing to this lack of nourishment, the aged failing little by little, destroy their life with a slow death without any fever.”32 The reference to dying “without any fever” gives an indication of the high death toll wrought by infection in our history. Death through infection would virtually always be accompanied by a significant fever. His commentary continues with a very modern health warning: “And this occurs through the lack of exercise since the blood is not warmed.”33

On the reverse side of this manuscript sheet (RL 19027 recto), next to a drawing of the blood vessels of the arm, Leonardo wrote probably the first description of a false aneurysm34 of an artery, in this case probably the brachial artery. This type of aneurysm is not actually an aneurysm, using the correct definition. It occurs when a hole is made in one side of an artery, usually by trauma. The extravasating blood is localised around the injury by the local tissues. The “aneurysm” is pulsatile and will grow progressively in size if not “bound up”. If it is controlled, the blood eventually will clot and the injury will stabilise. The situation described by Leonardo occurs following an injury to the antecubital fossa (the soft tissue area of flexion of the arm opposite to the elbow): “Veins are extensible and dilatable. And testimony of this is given by my having seen a man who by chance was wounded on the common vein [the median cubital vein or the brachial artery], and it was immediately bound up with a tight bandage. In the space of a few days, there grew up a [red] sanguineous abscess as large as a goose’s egg, full of blood; and so it remained for several years.”35

As with the rest of Leonardo’s anatomical work, this original contribution to medical knowledge remained hidden until long after others had begun to probe the same questions several centuries later. Among the first full descriptions was the one by John Hunter FRS in his casebooks.36

The Position and Status of the Heart

The special nature of the heart has been recognised throughout the history of anatomical exploration. The spiritual, emotional, and physical roles of the heart have always been interwoven. Although there is a predominance of discussion around the more subjective aspects, the physical (scientific) properties have been considered from earliest times. Aristotle, Hippocrates, and Galen all declared their beliefs with regard to the role of the heart. Its physical and spiritual place in the body was bound up together; its motion and its corporeal centrality vested it with importance.

Leonardo’s comment upon the central position of the heart in the body is sparse and terse. He placed it midway between the seat of the soul and the source of life, between the brain and the testis. He wrote, “The heart is placed exactly in the middle between the brain and the testicles.”37

He also spent time considering its position within the chest, describing it as lying obliquely, towards the left of centre. This he explained from the point of view of balance within the body. He stated that together with the spleen beneath, it counterbalanced the mass of the liver on the opposite side of the body.38 Elsewhere he ascribed the obliquity of the heart to the difference in weight between the right and left ventricles: “The right ventricle was made heavier than the left ventricle in order that the heart might be placed obliquely.” 39

He rhetorically discussed this concept in another passage, in which he argued against the comparatively heavier weight of the thicker-walled left ventricle acting as a counterweight to the right, with its greater volume of blood. In this passage he introduced the concept of the support of the heart by its great vessels. He wrote,

And if you say that the left exterior wall was made thick in order that it should acquire greater weight to form a counter weight to the right ventricle which has a greater weight of blood, you have not considered that such a balancing was unnecessary inasmuch all terrestrial animals except man carry their hearts lying horizontally. And likewise the heart of man lies horizontally when he lies in bed. But you would not be a good balancer because the heart has two suspensoria descending from the pit of the throat, and according to the fourth [proposition] of On Weights, the heart cannot be balanced unless it has above it one suspensorium only. These two suspensoria are the aortic artery and the vena cava. Furthermore, when the heart is deprived of the weight of blood on its contraction and gives it in deposit to the upper ventricles, the centre of gravity of the heart would then be on the right side of the heart and so the left side would be made lighter. But such weighting is not true, because as stated above, animals which lie down or stand on 4 ft have their hearts lying down [horizontally], and no such weighting of the heart is to be looked for. And if you say that the testicles are made only to open or close the spermatic ducts, you are mistaken, because they would only be necessary to rams or bulls which have very big [testicles]. And when these testicles had re-entered the body on account of the cold then coitus could not be performed. And the bat which sleeps and always places itself upside-down, how does it balance the right and left ventricles of its heart? 40

The concept of balance is illustrated by Leonardo in the small sketch of a man holding a long object in front of himself, with his feet carefully placed to maintain balance and his head and back also positioned as to maintain a balanced posture.41 This drawing is accompanied by a series of other small ones showing the heart attached to the great vessels and one in which the ventricles are dilated and contracted (Fig. 4.19a). The small diagrams at the top of RL 19084 recto also show the heart in relation to the great vessels in a similar way (Fig. 4.19b). It would appear from these diagrams that he correctly concluded that the heart is maintained in its position by its attachment to the great vessels and that the proposed balancing effects of the respective weights of the two ventricles were not a factor. The importance of the anchoring effect of the great vessels can be seen in victims of rapid deceleration injuries (such as head-on collisions), in whom the weight of the heart and its contained blood is thrown forward within the chest. If the force is great enough, the aorta will tear just before the point where it is anchored to the posterior chest wall. This injury, which always occurs just beyond where the vessels to the head and neck arise, is commonly fatal.

Fig. 4.19

The heart in relation to the great vessels. (a) Detail from RL 19087 recto, Studies of the heart, notes on light and shade, and a standing figure. Leonardo da Vinci. c. 1511–13. Pen and ink on blue paper (Lent by Her Majesty The Queen. Royal Collection © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II). (b) Detail from RL 19084 Recto, Studies of the heart, and notes on the vices of men. Leonardo da Vinci. c. 1511–13. Pen and ink on blue paper (Lent by Her Majesty The Queen. Royal Collection © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II)

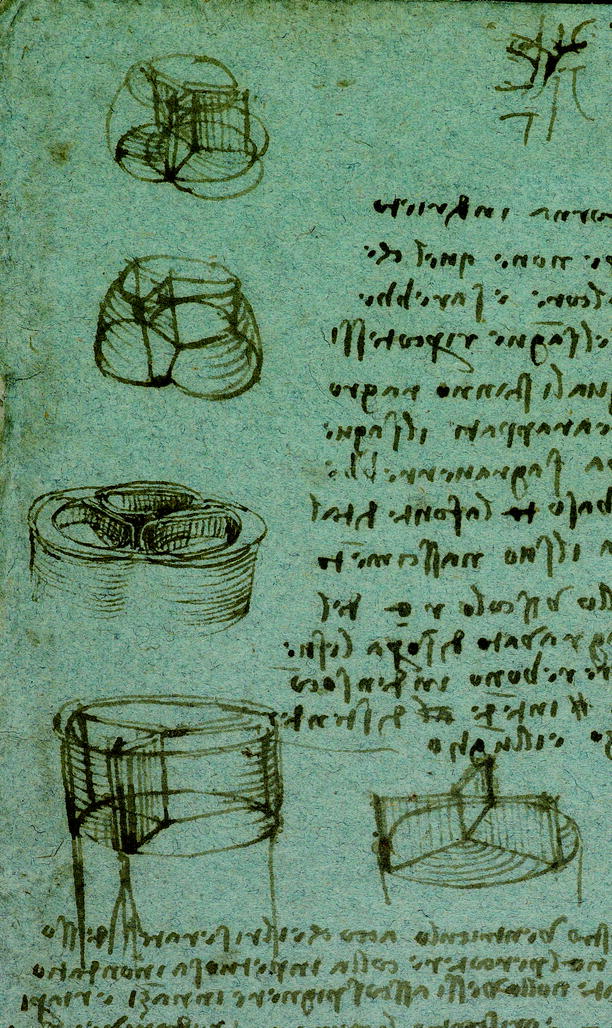

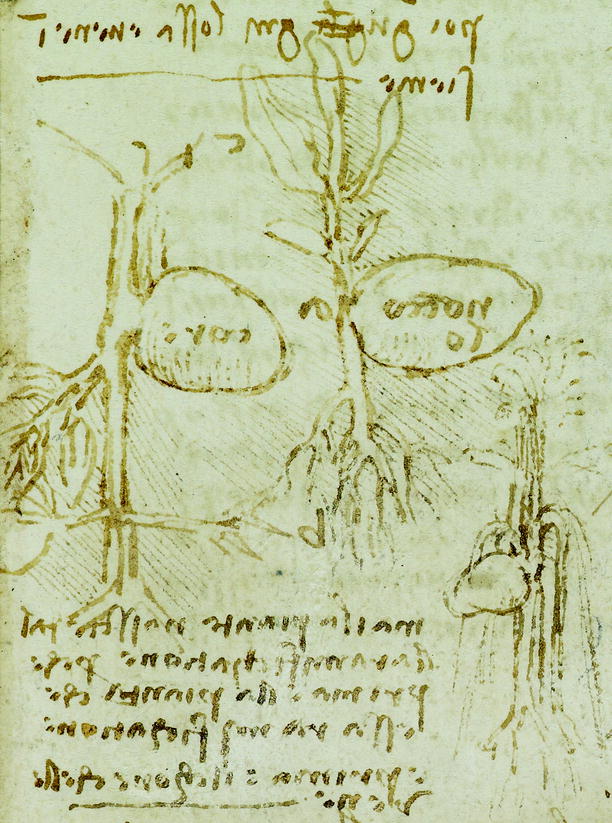

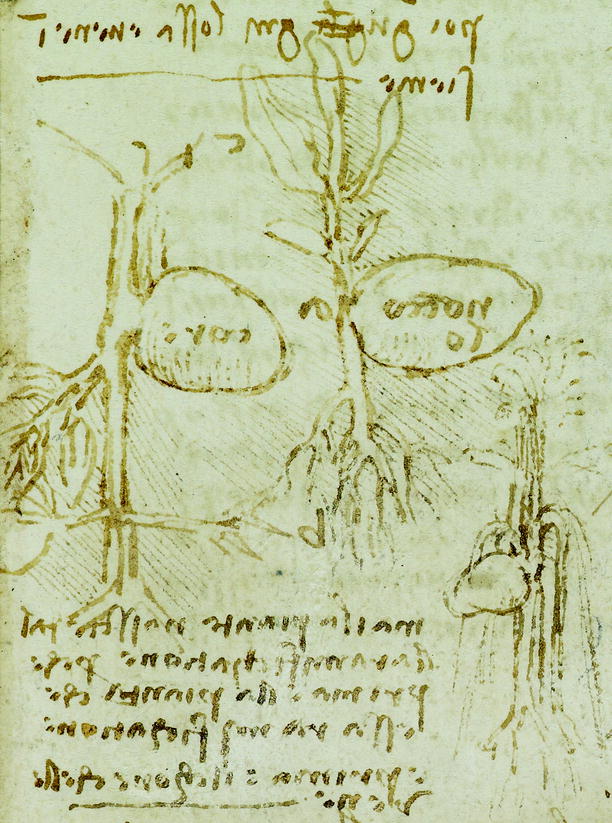

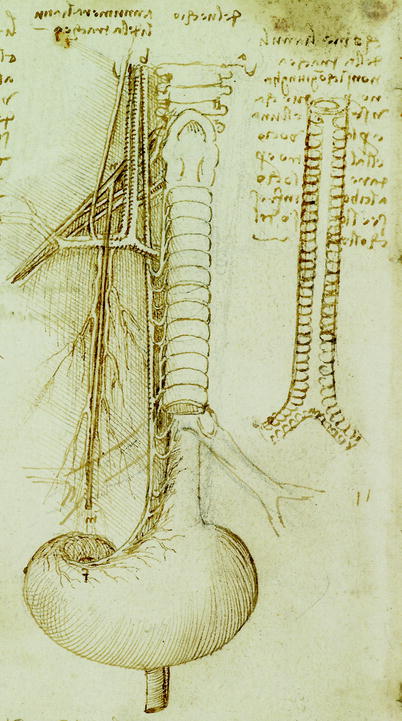

Galen declared that the liver was the principal organ of the body, being the first to be formed, and as such was the source of all the blood vessels. Aristotle held another view, suggesting that the heart was the principal organ. More than a millennium later, Leonardo entered into this debate and concluded on the side of Aristotle that the heart had pride of place over the liver as the origin of the blood vessels. This he argued from a wider natural perspective using visual and verbal metaphors. He likened the heart to a seed or a nut, and wrote, “The heart is the nut which generates the tree of the veins; which veins have their roots in the manure, that is the meseraic [mesenteric] veins go on to deposit the blood they have acquired in the liver, whence then the upper veins of the liver [hepatic veins] are nourished.”42 Accompanying this text are two simple drawings, one with the word “nut” (noccollo) written at its centre and the other with the word “heart” (core) in the same place (Fig. 4.20). Near to them are the words, “A plant never arises from its branches, for the plant exists before the branches and the heart exists before the veins.”43 In the drawing labeled “heart” can be seen a simple representation of the vessels to the liver joining the inferior vena cava below the heart. In the parallel drawing, the roots and branches are shown directly emanating from the side of the seed. The visual analogy is clear.

Fig. 4.20

The metaphor of the seed for the heart in an explanation of why the heart must be the source of the great vessels. Detail from RL 19028 recto, The heart compared to a seed. Leonardo da Vinci. c.1508. Pen and ink over black chalk (Lent by Her Majesty The Queen. Royal Collection © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II)

Beside these small drawings is a more substantial one illustrating this important relationship of veins and arteries to the heart, the sovereign power. The major text on that sheet affirms in no uncertain terms this relationship:

All the veins and arteries arise from the heart; and the reason is that the biggest veins and arteries are found at their conjunction with the heart. And the more they are removed from the heart the finer they become, and they divide into very small branches. And if you say that the veins arise in the gibbosity of the liver because they have their ramifications in this gibbosity, just as the roots of plants have in the earth, the reply to this comparison is that plants do not have their origin in the roots, but the roots and other ramifications take origin from that lower part of the plant which is situated between the air and the earth. And all the lower and upper parts of a plant are always less than this part which adjoins the earth. Therefore it is evident that the whole plant takes origin from such a size and in consequence the veins take their origin from the heart where they are biggest. Never does one find a plant which has its origin from the tips of its roots or other branches; and this observed by experience in the sprouting of a peach which arises from its nut as is shown above at a b and a c.44 (The labels are clearly seen on the accompanying small drawings.)

Thus, in the opinion of Leonardo, the heart has pride of place within the body and is the source of all of the blood vessels.

The Nature of the Heart

As the heart is the only continuously moving part of the body, it is natural that investigators should look to it as a vital force in life. Its responsiveness to emotional change led to an extended debate as to its role in generating the emotional state as well as the viability of the whole animal. With the benefit of evolving investigative technologies, we have been able to demystify this crucial organ to the extent that we recognise the heart as a highly responsive, self-regulating muscle pump, which is the engine of the circulation. This statement seems obvious to us, but in the time of Leonardo, even the fact that it is made of muscle had not been established. This was Leonardo’s first significant contribution to the practical understanding of the heart.

Modern biology recognizes three distinct forms of muscle: (1) Skeletal muscle, the most abundant form, which is responsible for the mobility of the animal. It has the microscopic characteristic of stripes running horizontally across its fibers, giving it the alternative name of striated muscle. (2) Smooth muscle, so called because it lacks the microscopic stripes of skeletal muscle. This type is found in places such as the eye and the bowel. It responds to chemical and autonomic nerve stimulation with such actions as the focusing of the eye and the movement of the gut. (3) Cardiac muscle, the unique muscle of the heart. It too is striated under the microscope, but the muscle fibers have branched endings, which interdigitate with the surrounding muscle fibers, forming a syncytium.45 It has the property of continuous contraction and relaxation throughout life. It responds to chemical and nervous stimuli, driven in turn by exercise and emotional change.

There was no way of distinguishing these forms of muscle until the development of the microscope in the late sixteenth century, when It became possible to discern their different characteristics. Until then, differences could be determined only by examination of gross form and function. Galen recognised that the tissue of the heart was different and described it as having a special “hard” flesh. Whilst recognising that it was constructed of fibres resembling muscle, both he and Avicenna a millennium later said that it was in reality quite a different material.46 In contrast to this position, Leonardo clearly stated that the heart was made of muscle. He recognised its difference from skeletal muscle in describing it as being of greater density. In support of his claim that it was a muscle, Leonardo pointed out that it possessed its own arterial blood supply and venous drainage: “The heart of itself is not the beginning of life but is a vessel made of dense muscle vivified and nourished by an artery and a vein as are the other muscles. It is true that the blood and the artery which purges itself in it are the life and nourishment of the other muscles.”47

In Galenic terms, the heart was perceived as having three specific roles: the movement of blood to the lungs and the periphery; drawing air from the lungs into the heart during the relaxation and filling phase of the ventricles; and generating the heat of the body, through its often-violent movement. Leonardo held to that philosophy, although, as we shall see, he began to question the direct connection between the trachea and the heart. A considerable amount of Leonardo’s writing on the heart is spent in considering its role in the generation of innate heat. He perceived that several of the components and structural relationships in the heart are defined by their contribution to this vital function.

The presence of bodily heat in an animal implies life, and Leonardo stated that assumption as follows: “Where there is life there is heat, and where vital heat is, there is movement of vapour.” 48 The last phrase of this quotation refers to the creation of convection currents within fluids, be they in the liquid or gaseous phase. Hot air and hot water rise, whilst the opposite is true for cold liquids.

In keeping with the beliefs of his time, Leonardo accepted the four elements of the universe—earth, water, air, and fire—and he saw the constitution of man as a reflection of the world around him and as such, as a part of the microcosm/macrocosm continuum:

By the ancients man was termed a lesser world and certainly the use of this name is well bestowed, because, in that man is composed of water, earth, air and fire, his body is an analogue for the world: just as man has in himself bones, the supports and armature of his flesh, the world has the rocks; just as man has in himself the lake of the blood, in which the lungs increase and decrease during breathing, so the body of the earth has its oceanic seas which likewise increase and decrease every 6 h with the breathing of the world; just as in that lake of blood the veins originate, which make ramifications throughout the human body, similarly the oceanic sea fills the body of the earth with infinite veins of water. The nerves are lacking in the body of the earth…. But in all other things they are similar.49

Therefore it was natural for him to use examples from the wider world in his explanations of the inner workings of the human body. At work within the four elements were the four powers of nature: weight, force, movement, and percussion. The resistance between bodies, of which at least one was moving, creates friction.50 Simple friction creates heat, and this Leonardo reflected in two statements on the production of heat within the heart: “And the revolvings made by the blood whirling round in itself in different eddies, and the friction that it makes with the walls and the percussions in the recesses [the spaces between the pectinate muscle bundles of the right atrium], are the cause of the heating of the blood, and of making the thick viscous blood fine….”51 and “On The Cause Of The Heat Of The Blood: The heat is generated by the movement of the heart; and this is evident because the more quickly the heart moves the more the heat multiplies, as the pulse of febrile persons moved by the beating of the heart teaches us.” 52

A further use of natural analogy is found in other comments, in which he uses a river and a lake as similes for the blood flow and the heart. Here he is restating his belief that the ebb and flow motion of the blood is essential for the generation of heat:

And such motion of the blood would behave like a lake through which a river flows, which acquires as much water from one side as it loses at the other. However, the only difference is that the movement of the blood is discontinuous and that of the river flowing through the lake continuous and from this lack of flux and reflux the blood would not be heated and consequently the vital spirits could not be generated and for this reason life would be destroyed.53

Leonardo’s concept of the heart as a source of renewable heat is evidenced in the following words: “As natural warmth spread through the human limbs is driven back by the surrounding cold which is its opposite and enemy flowing back to the lake of the heart and the liver fortifies itself there, making of these its fortress and defence.”54

Within Leonardo’s interpretation of the necessity of the generation of heat by the movements of the heart was his insistence that the heating of the blood caused it to be less viscous and thereby to pass more easily through the fine pores in the interventricular septum, as described by Galen:

Because the heat of the heart is generated by the swift and continuous movement which the blood makes by its friction within itself through its eddyings, also by the friction it makes with the pitted walls of the right upper ventricle into which it continually enters and escapes with impetus, these frictions made by the velocity of the viscous blood heat it, subtilise it, and make it penetrate through the fine meati [pores], giving life and spirit to all the organs into which it is infused.”55

Leonardo used another example at another place in his notes to prove that continuous movement produces heat. In this case, he used the making of butter by the churning of milk as an example of heat production through motion. A difference with this argument is that in this process, the liquid milk becomes more viscous, whereas he argues that blood becomes “thinned”. This observation recognises the difference in response to the motion of different liquids, which is predicted by the content of the liquid. The extreme example is that of a thixotropic liquid, one that is extremely viscous at rest (more like a gel), so that it will not flow. The energy imparted to it on violent agitation makes it much less viscous and allows it to flow freely for a while, but the as the energy is expended, the liquid returns to a gel state56:

Observe whether the revolution of milk when butter is made, heats it. And by such means you will be able to test the strength of the auricles of the heart which receive and expel the blood from their cavities and other passages; these being made only in order to heat and refine the blood and make it more quickly penetrate the wall through which it passes from the right into the left ventricle57 where through the thickness of its wall, that is, of the left ventricle, it conserves the heat which the blood carries to it.58

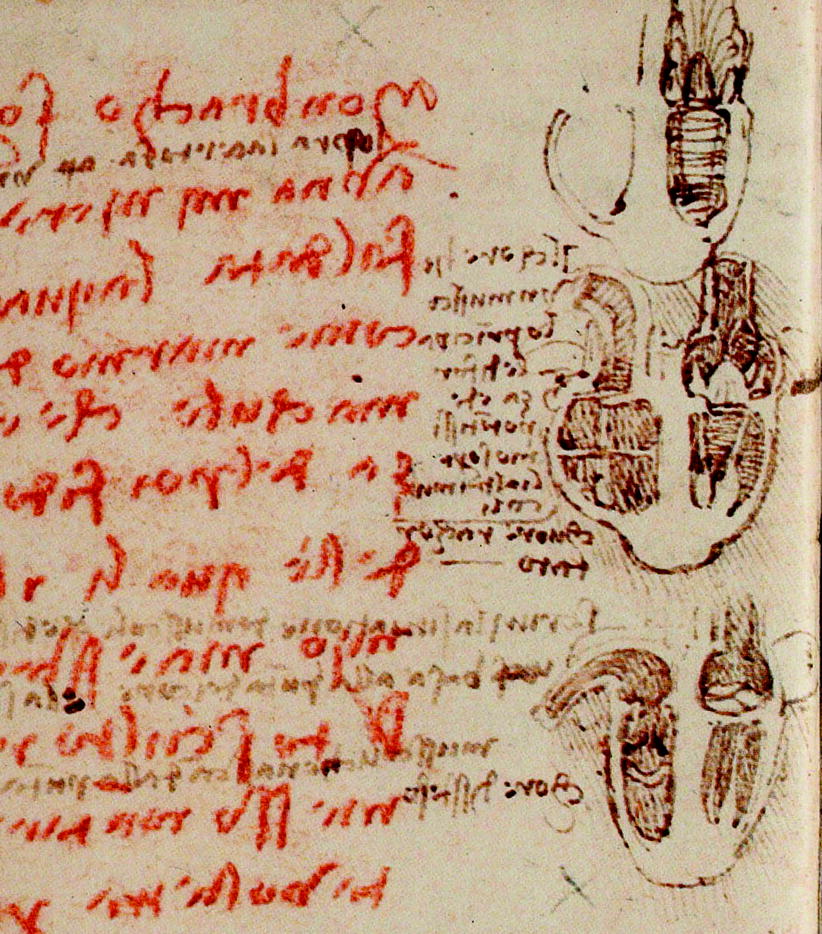

The analogy of the heart as a stove or a furnace is to be found on a page in the Codex Arundel.59 There Leonardo illustrates a stove with an inlet and an outlet valve, which he labels “m” and “n”. Writing about this stove, he regards the heart as the furnace and the trachea as the chimney. The air is drawn in through one opening labelled “n” and is blown out in the other direction through an opening labelled “m”. Leonardo likens this to the cardiorespiratory system: “Short and frequent breathing suffocates the person, short because each breath does not change all of the air in the lung that has been heated. But a part of it remains there so greatly heated that it would do great damage to an animal unless big and long breaths were to drive it out of the lung.”60

This analogy is carried over into an early drawing in the Windsor series, in which he labelled the two tubular connections to the lung in the same way “n” and “m”. 61 In one part of the drawing, the labelled connections can be seen intact; another part shows the same view in cross section. Leonardo explains that they are the inlet and outlet for the products of combustion in the heart. The style and substance of this drawing suggest a date earlier than the final heart series of 1513–1514. Clark62 and O’Malley and Saunders63 date this and a similar drawing (RL 19112 recto) as 1504–1507.

Having established that the heart was in this way a “furnace”, Leonardo had to adopt another property for heart muscle, namely its ability to withstand heat. He wrote, “The heart is of such density that fire can scarcely damage it. This is seen in the case of men who have been burnt, in whom, after their bones are in ashes, the heart is still bloody internally. Nature has made this great resistance to heat so that it can resist the great heat which is generated in the left side of the heart by means of the arterial blood which is subtelised in this ventricle.”64

In reality, contracting muscle does generate heat. The obvious example is skeletal muscle on extreme exercise. Similarly, the heart produces more heat with increasing exercise, and this heat is dissipated in the blood flowing through it via the coronary arteries and the main stream of blood. The heat is then dissipated in the periphery by sweating and through the lungs in breathing. All metabolic processes in the body operate under the control of enzymes (biochemical catalysts), and these operate within limited temperature bands. Heat control is therefore very important for normal muscle function, albeit as part of a very different concept than that imagined by Leonardo.

The actions of the heart when an individual is at rest are barely perceptible. As exercise levels increase, however, its motion becomes increasingly forceful and obvious. At extremes of exercise, its movement can feel almost violent, producing a pounding in the chest and head and a bounding peripheral pulse. These enormous and sustainable reserves of power were recognised by Leonardo in the following words: “The heart is a principal muscle of force, and it is much more powerful than the other muscles.”65 As one of the four great powers, Leonardo’s use of the term “force” was specific. His definition was as follows: “a spiritual energy, an invisible power which is created and imparted, through violence from without, by animated bodies to inanimate bodies, giving to these the similarity of life, and this life works in a marvellous way, constraining and transforming in place and shape all created things. It speeds in fury to its undoing and continues to modify according to the occasion.”66

Galen’s heavy reliance on the “vital spirits” for the satisfactory explanation of the viability of an animal led to his perceived importance of the relationship between the heart and the lungs for the extraction of the vital spirit, “pneuma” As we shall see later, access of “pneuma” to the heart was supposedly through the trachea. During the ventricular relaxation phase of the cardiac cycle, air is drawn from the trachea into the ventricle and was supposed to mix with the blood, re-entering the right ventricle after contraction of the atria. On the next right ventricular contraction, part of the blood (now enriched with pneuma) would be forced through the imaginary septal pores and depart through the aortic valve on its way to the brain. Unlike Galen, Leonardo’s writing lacks frequent reference to the “vital spirits” and places much heavier emphasis on the four powers of nature,67 but he does spend some effort in trying to demonstrate this fictional relationship.

Although much of Leonardo’s text on the function of the heart relates to the flux and efflux of pulmonary blood flow, it is clear from these lines that he was well aware of the importance of the heart in providing the flow of blood to the periphery. He stated as much in a section describing the way that an animal sustains itself by the consumption of nutrition: “And the same thing happens in the bodies of animals by means of the beating of the heart which generates a wave of blood through all the vessels which continually dilate and contract. And dilatation occurs on the reception of superabundant blood and diminution occurs on the departure of the superabundance of the blood received. This, the beating of the pulse teaches us when we touch the aforesaid vessels with our fingers in any part of the living body.”68

Therefore, to Leonardo the heart was a muscle pump of considerable power, capable of withstanding great heat. He perceived it as the source of propulsion in the ebb and flow movement of the blood, as well as the generator of heat.69

The Movement of the Heart

“Of the heart: This moves of itself and does not stop unless forever.”70

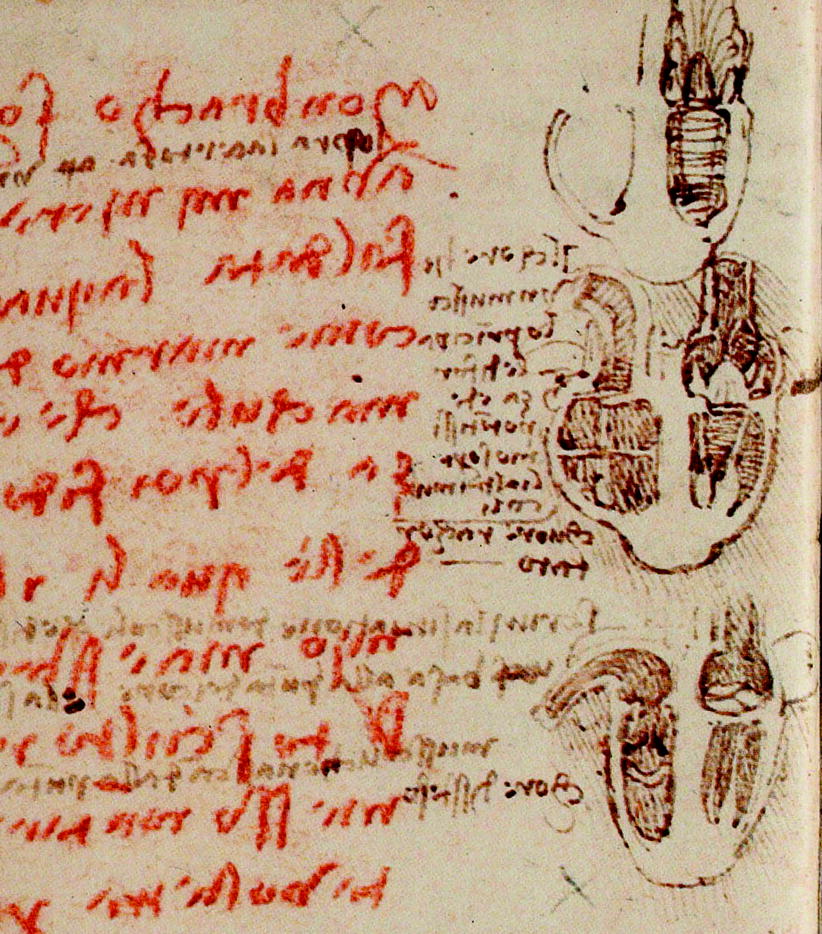

The lifelong continuous contraction and relaxation of the heart sets it apart from all of the other organs in the body. It follows. therefore, that having proved to his satisfaction that it was made of a sturdy and most powerful form of muscle, Leonardo should ponder on the cause of this continuous motion. He asked himself, “And which part of the heart it is which is the cause of its movement; and whether it is inside or outside the heart”.71 We know that this continuous movement of the heart is activated by the spontaneous generation of a wave of cellular depolarisation that originates in the sinoatrial node and spreads throughout the heart. At rest, this occurs about 70 times a minute. It changes in response to exercise and emotional challenges. This change is moderated in part by a nerve originating in the brain called the vagus nerve (cranial nerve X). Leonardo was aware of this nerve and referred to it as the reversive nerve. It was given this name by earlier anatomists because on the left side of the body, it reverses its direction in the chest. After arising from the brain, it runs from the base of the skull to the abdomen. In the chest, it divides as it passes around the aorta, and part of it returns to supply the vocal cords of the larynx. The rest of the nerve continues along the pericardial sac surrounding the heart and continues into the abdomen, where it provides important stimuli for the normal function of the gut. On the right side of the body, it divides and reverses its direction higher up in the neck, looping around the right subclavian artery. As it passes over the pericardium, branches penetrate the heart and their activation contributes to the control of heart rate. This nerve is clearly shown in Leonardo’s drawing on RL 19050 verso (Fig. 4.21). In a personal record of his dissection of this nerve as part of his attempts to discover more about its anatomy and its role in the control of heart muscle contraction, Leonardo wrote, “The reversive nerves arise at a b, and b f is the reversive nerve descending to the pylorus of the stomach. And the left nerve, its companion, descends to the covering of the heart, and I believe that it may be the nerve which enters the heart.”72

Fig. 4.21

The vagus (reversive) nerve and its branches. Detail from RL 19050 verso, The distribution of the right vagus and right phrenic nerves. Leonardo da Vinci. c.1508. Pen and ink over black chalk (Lent by Her Majesty The Queen. Royal Collection © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II)

The following quotation forms part of Leonardo’s investigation of the opposing Aristotelian and Galenic positions on the seat of the soul using the role of the vagus as the arbiter:

Do not fail to follow up the reversive nerves [vagi] as far as the heart; and see whether these [nerves] give movement to the heart, or whether the heart moves by itself. And if such movement comes from the reversive nerves, which have their origin in the brain, then you will make it clear how the soul has its seat in the ventricles of the brain, and the vital spirits have their origin in the left ventricle of the heart. And if this movement of the heart arises from the heart itself, then you will say that the seat of the soul is in the heart, and likewise to the other nerves because the motion of all muscles arises from these nerves which their ramifications are infused into the muscles”.73

Though couched in the terms of his time, this discourse by Leonardo illustrates the use of rhetorical argument in an attempt to resolve a problem. The activity of the brain does control the activity of the vagus nerve, which in turn has an identifiable effect on the heart. Our heart rate quickens and slows in response to our emotional state. In this approach, Leonardo further allied himself with the view that the seat of the soul is the brain and not the heart. It is interesting to note that the movement of the heart was not understood by Harvey, who claimed that the movement of the heart was not spontaneous. He suggested that the vital spirits contained within the blood were the source of the heart’s movement.74