(1)

Department of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery, Papworth Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, Cambridge, UK

Abstract

No other subject engaged Leonardo more than his work on the anatomy of the human body. It was the subject in which he argued most forcibly for the importance of independent observation allied to original thought. This process he called “experience” of the world around him “gained through the senses” was his starting point for new understanding. Reason and contemplation brought to bear on the sensed experience allowed the development of a hypothesis. Experimental testing and mathematical proof then gave authority to that hypothesis, the veracity of which could be stated. This approach, proclaimed by Leonardo as essential for rational progress, presages the modern method of science.

No other subject engaged Leonardo more than his work on the anatomy of the human body. It was the subject in which he argued most forcibly for the importance of independent observation allied to original thought. This process he called “experience”1 of the world around him “gained through the senses” was his starting point for new understanding. Reason and contemplation brought to bear on the sensed experience allowed the development of a hypothesis. Experimental testing and mathematical proof then gave authority to that hypothesis, the veracity of which could be stated. This approach, proclaimed by Leonardo as essential for rational progress, presages the modern method of science.

This reliance upon dependent observation, throwing off the cloak of didactics, clearly brought him into conflict with some of the academics of the day. He can be heard to rail against his detractors who seem to be criticizing him for original thought; though the context may have been more general, the control on perceived wisdom by the physicians of the day would seem a likely target. Leonardo wrote:

Many will think that they can with reason blame me, alleging that my proofs are contrary to the authority of certain men held in great reverence by their inexperienced judgment, not considering that my works are the issue of simple and plain experience which is the true mistress. These rules enable you to know the true from the false—[The rules that he refers to are those that we would speak of as scientific method.]—and this induces men to look only for things that are possible and with due moderation—and they forbid you to use a cloak of ignorance, (allowing the enquirer to admit that he does not know the answer) which will bring about that you attain to no result and in despair abandon yourself to melancholy.

I am fully aware that the fact of my not being a man of letters may cause certain presumptuous persons to think that they may with reason blame me, alleging that I am a man without learning. Foolish folk! Do they not know that I might retort by saying, as did Marius2 to the Roman Patricians, ‘They who adorn themselves in the labours of others will not permit me my own.’ They will say that because I have no book learning, I cannot properly express what I desire to treat of—but they do not know that my subjects require for their exposition experience rather than the words of others. Experience has been the mistress of whoever has written well; and so as mistress I will cite her in all cases.3

Perhaps the melancholy he speaks of refers to his own state of mind in dealing with the obdurate academics that clearly were scoffing at his work. He was an original thinker prepared to think outside of the box, and his preparedness to challenge ancient accepted authority can be found in these words, which open the passage quoted above: “Consider now, O reader! What trust can we place in the ancients, who tried to define what the Soul and Life are—which are beyond proof—whereas those things which can at any time be clearly known and proved by experience remained for many centuries unknown or falsely understood.”4

The dominant academic force in anatomical teaching of the period (and for more than a century before and afterwards) was the work of the Greek physician Galen, who was born in Pergamum, on the seaboard of Asia Minor, in 129 A.D. Galen, who was physician to the gladiators, amongst other things, declaimed Hippocrates’ stance on the importance of knowledge of anatomy in the understanding of the human condition. Galen wrote, “He [Hippocrates] thought that one should have a precise understanding of the nature of the body, that this was the source of the whole theory of medicine.”5 As we shall see, Galen did not completely hold to that proclamation himself.

Galen’s anatomy was based upon the dissection of animals, principally monkeys; he argued that as a result of their external similarities, their internal form would mimic that of the human being. As a result, there were considerable inaccuracies in his descriptions. Despite maintaining the position that anatomy had an important role, Galen’s therapeutic approach to disease was based on the balance or imbalance between the four humors—blood, yellow and black bile, and phlegm—so the role of anatomy in the diagnosis of medical conditions was very limited. In both Galen’s and Leonardo’s time, knowledge of the superficial veins and arteries was important for the barbers who “let blood” from the sick, and knowledge of muscle, bones, and joints was important for the surgeons, who dealt mainly with trauma. Beyond these uses, however, there was little practical application for more advanced anatomy, other than demonstration to medical students of the structures that Galen described.

Galen was much more than just a physician, and he considered it impossible to be a doctor without a full knowledge and use of the canonical branches of philosophy (namely logic, physics, and ethics). This approach brings the disciplines of philosophy and medicine inextricably together. Galen wrote of this in the De anatomicis administrationobus. He said that there are applications for anatomy “that are more useful for philosophers than for physicians.”6 He continued, “Of what use to aetiology, diagnosis and treatment [of disease] could a knowledge of the muscles of the tongue or of the muscles, nerves, arteries and veins that run through the heart and viscera if it was impossible to act upon them in any way?”7 Herein lay the context in which Leonardo was drawn so heavily into the challenge of understanding the human body. Not specifically to derive information that would be of use to the physicians and surgeons of the day but more to answer questions within the confines of Natural Philosophy.

Interestingly, as Andrea Carlino points out in his excellent book, Books of the Body,8 this epistemological approach discussed by Galen affected the reception of Vesalius’s de Fabrica in the general medical world for several decades, with the continuation of the ritualisation of dissection for didactic ends and as a visual aid to the textbooks of the day, rather than developing the craft of dissection as a research tool, as Vesalius championed.

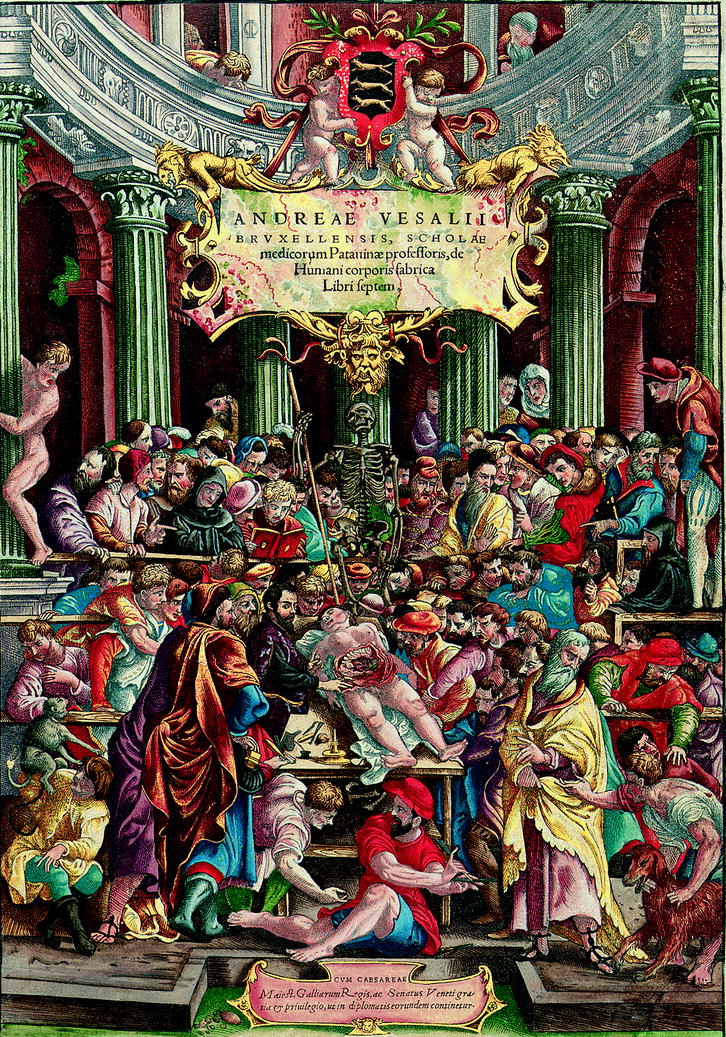

Leonardo’s work and his ideas on “experiencing the truth” through dissection discussed in his manuscripts predated Vesalius’s standard-setting De Humani Corporis Fabrica (1543) and others such as the De Re Anatomica of Realdo Colombo (1559) by a generation. Sadly, as Leonardo did not publish any of this work, there was no way that he could be recognized for the originality of his approach.

With this setting in mind, the observer can only marvel at the insightful questions that Leonardo asked of himself and the outstanding quality of dissection that was necessary to reveal aspects of previously unknown parts of anatomy. These skills, allied to the originality and sheer beauty of the representation to be found in his drawings, make his work quite extraordinary. Also, although his anatomical work was known about by authorities of the time and is referenced with significance in Vasari’s Lives of the Great Artists and Sculptors, there is no reference to it in the authoritative anatomical texts of his or the next generation. Vesalius produced de Fabrica whilst working in Padua.

The comparatively primitive work of the anatomist/physicians de Ketham and Berengario exemplifies the world of anatomy in Leonardo’s time. It must be stated, however, that Berengario in his Commentaria corrected some aspects of Galen’s work and was committed to carrying the specialty forward. He wrote, “We know how to carry out science by adding parts to other parts: and we are as children standing on the shoulders of giants: we are able to see much farther than antiquity could.”9

Although it took time,10 it was in this setting that Vesalius’s work was able to make such an enormous impact. Yet Leonardo had developed the inquisitive approach to anatomy decades earlier. His progress from a standing academic start, though disappointing to him, was enormous. The picture emerges, however, of a few other farsighted men who appreciated the relevance and importance of original thought. Again, Berengario wrote, “And in this discipline nothing is to be believed that is acquired either through the spoken voice or through writing: since what is required is seeing and touching.”11 In fact, he goes on to stress that Galen should not be followed “where seeing and touching [Leonardo’s experience] are in opposition.” Leonardo’s attitude antedates these sentiments and indeed may have stimulated them. Berengario was an approximate contemporary of Leonardo, being born in 1460 and attending Bologna University. His Commentaria was not published until after Leonardo’s death (1521), but Leonardo may well have known of Berengario’s stance on anatomical exploration. Berengaria was a considerable collector of art and had dealings with Raphael, so he is likely to have been aware of Leonardo’s prowess in the arts world.

The importance of the subject to Leonardo is clear from the breadth and depth of his work as well as from the sheer volume of extant material. Bearing in mind that much has been lost, this body of his work is very substantial indeed and suggests a great deal of time spent looking and dissecting, in addition to the many hours of writing and drawing that his manuscripts reflect.

His study of anatomy spans three decades of his life. If, as seems most likely, he was first stimulated to learn anatomy for use in his artistic endeavors, what then drew him into the world of what effectively became a research scientist? His studies of proportion and the muscular and skeletal anatomy fit well with that of an artist struggling to achieve perfection in the representation of the human form in motion and at rest. His detailed analyses of the viscera and the cardiovascular and central nervous systems are something quite different.

A clue to this interest can be found in an interesting note on the earliest page of his extant anatomical notes. Dated as early as 1482 by some influential scholars and headed “Tree of vessels,” this drawing of a man standing with legs apart and arms partially outstretched looks as though it may have been drawn to help those who may wish to “let blood,” as the major arteries and veins are drawn in.12 It also has a representation of some of the internal organs, namely the heart, liver, and kidneys. To the left side of the page is a note reminding him to “Cut through the middle of the heart, liver and lung and kidneys that you may entirely figure the tree of vessels.” These internal vital organs he refers to as “The Spiritual parts,” suggesting perhaps that their investigation linked more to philosophical enquiry than the practical.

Anatomy in the Time of Leonardo

The first records of dissection of the human body arise in Alexandria during the third century B.C. Surprisingly, from that time until the fourteenth century there is no reliable archival record of formal human dissection taking place, including in the work of Galen, whose anatomy (as pointed out earlier) was based on animal dissection.

In Leonardo’s time in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, dissection as practiced amongst physicians was largely in the form of autopsy to establish or confirm the cause of death. Interpretation of the findings was very limited by the teaching of the time, which was based upon the idea that the driving forces in the body were rooted in the relationship between the four elements of nature—earth, air, fire, and water—and the four humors of man—black bile (earth), blood (air), yellow bile (fire), and phlegm (water). The lack of equilibrium resulting from the predominance of one force over another gave rise to what Leonardo called the four dispositions of man: melancholy, choleric, sanguine, and phlegmatic.13 In this framework, the body was seen to be “opened” for inspection rather than to be systematically dissected. In the writings of Mundinus and Avicenna, the body was seen as three cavities: the abdomen, the thorax, and the skull. The surgeon anatomists considered the limbs separately, with the purpose of structural repair. The first cavity to be opened would have been the abdomen because of the rapid putrefaction of the parts found therein after death. Also, for this reason, dissection tended to be exclusively a wintertime activity. Leonardo’s own commentary on dissection powerfully displays the distasteful nature of the task:

“And though you have love for such things you will perhaps be hindered by your stomach; and if that does not impede you, you will perhaps be impeded by the fear of living through the night hours in the company of quartered and flayed corpses fearful to behold. And if this does not impede you will lack the good draughtsmanship which appertains to such representation; and even if you have the skill in drawing it may not be accompanied by a knowledge of perspective; and if it were so accompanied, you may lack the methods of the geometrical demonstration and methods of calculating the forces and strength of the muscles; or perhaps you will lack patience so that you will not be diligent. Whether all these things were found in me or not, the 120 books composed by me will give their verdict yes or no. In these I have been impeded neither by avarice or negligence but only time. Farewell.”14

Several professional groups were interested in the body and its workings. At the head of the professional hierarchy were the physicians, who rated themselves on a par with the philosophers as part of the liberal arts. Thus they could not be seen to partake of manual occupations but worked within the academic boundaries of natural philosophy. Below them were the surgeons, barbers, and apothecaries, who worked at the bidding of the physician. In addition to these groups were the midwives, the empiricists, and, of course, the charlatans!

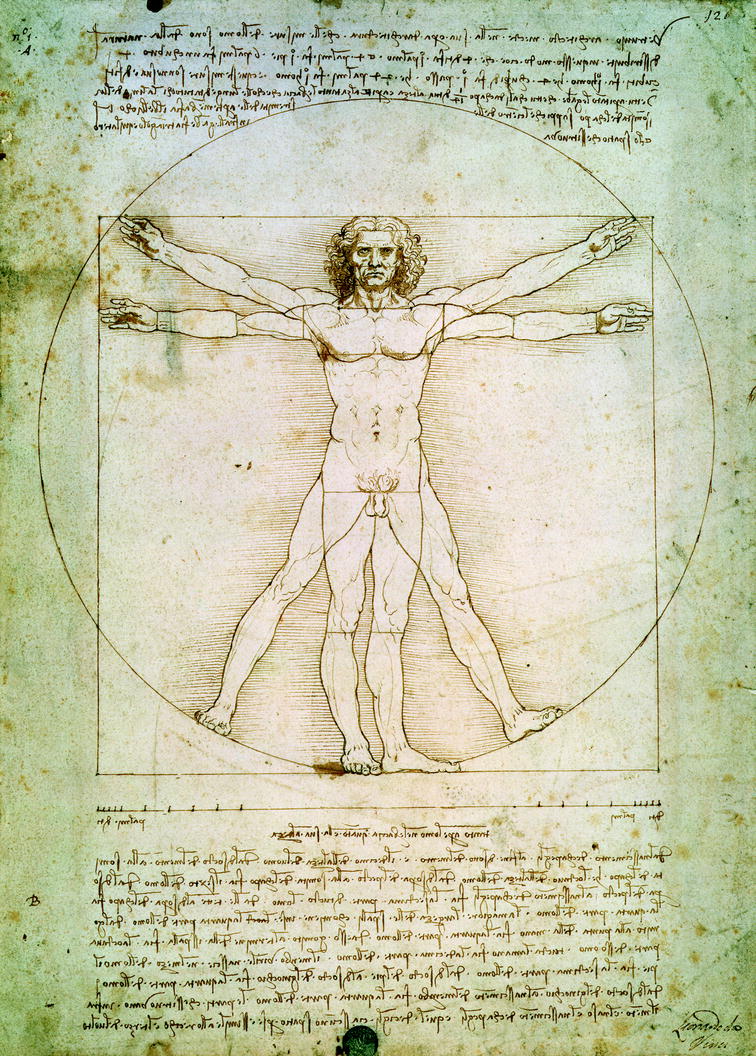

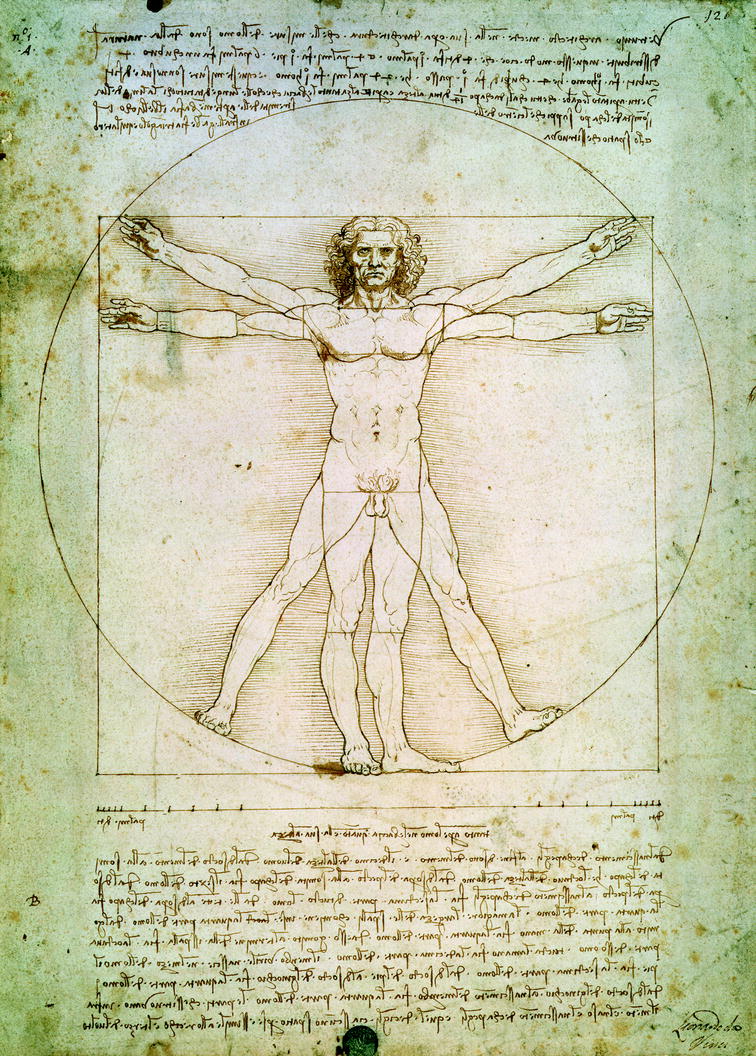

Furthermore, as practitioners of the liberal arts, architects were interested in the perspectival aspects of the human frame. Francesco de Giorgio and Alberti were influenced by the writings of the first century Roman architect, Vitruvius. His famed ten books on architecture were composed in the first century A.D. and were to architecture what Galen was to medicine. Leonardo was familiar with and significantly influenced by Vitruvius and by Alberti’s interpretation of Vitruvius. One of the manifestations of this influence was the various forms of imagery of the iconic Vitruvian man.15 For Vitruvius and his followers, the body was seen as a cultural entity. The standard layout of a church, which is based upon the head as the chancel, the extended arms as the side chapels, and the remainder of the body as the nave, can be found in di Giorgio’s manuscripts on architecture, a volume possessed by Leonardo. Leonardo’s own iconographic image of the Vitruvian man fits directly into this paradigm (Fig. 2.1).

Fig. 2.1

Leonardo’s Vitruvian man. BAL 4146. The Proportions of the human figure (after Vitruvius), c.1492 (pen & ink on paper), Vinci, Leonardo da (1452–1519)/Galleria dell’ Accademia, Venice, Italy/The Bridgeman Art Library

The use of anatomical knowledge in the development of philosophical ideas about man’s place in the cosmos cannot be overstated. The question of how the human body was made pertained as much to natural philosophy as to natural science. This positioning of anatomical knowledge within the sphere of philosophy continued to be influential upon Leonardo, as one would expect from his reading of the texts of the day. Indeed, Vesalius defines anatomical discipline in de Fabrica as belonging to natural philosophy.

Strict rules controlled access to human cadavers for dissection. To preserve anonymity, the unfortunate subject had to have been domiciled in an area distant from the place of dissection. He or she had to have been convicted of unpleasant crimes and not be a Catholic, but preferably of Jewish origin. The element of societal control was very important. Public dissections, which went on over several days, were highly ordered. In some cases, they were organized as the end phase of an execution. In such cases, the process was planned as two separate steps with significant ceremony. By such means was the sanctity of the human body managed and maintained.

Where Vesalius, and indeed Leonardo before him, broke with tradition was in their belief that the detailed structure of the human body should be studied for itself, independently of its relevance to the practice of medicine. Thus the study of anatomy as an independent scientific discipline began in the middle years of the sixteenth century. As a result of this new exploration of the anatomical universe of the human frame, there was an inevitable reevaluation of Galen’s ideas and an improved record of observations on anatomy. This change was at first more subtle than might have been expected. In Berengario da Carpi’s commentaries on the text of Mundinus,16 and also in Vesalius’s de Fabrica,17 neither man was explicitly critical of his forebears, but utilized their experience from dissection as a means to point out differences in their developing knowledge base from that of Galen and Mundinus.

In the same period, philosophers were using anatomical insight to provide indisputable evidence of the supreme authority of the principles that inform man and nature. These questions largely revolved around the female form and the process of conception. This philosophical stance has reverberations in the words of Leonardo in his reference to the marvelous works of nature and man: “And would that it might please our creator that I were able to reveal the nature of man and his customs as I describe his figure!”18

The legitimacy of dissection in this period is often questioned. It has been suggested that the Vatican had banned dissection. Pope Bonefacio VIII issued a Papal Bull in 1299, declaring that there should be no separation of the parts of the human body and no boiling of these separated parts. This has been taken as a prohibition of anatomical dissection, but in fact it was nothing of the kind. This Bull was declared in response to the attempts to preserve parts of the bodies of noblemen (and occasionally women) who died on the Crusades and whose relatives and friends did not want them buried in the unconsecrated ground of the Muslim homelands. The separation and boiling was to allow a degree of preservation of the tissues for repatriation of the parts for burial at home. Separation of the body into parts also allowed for several burial sites, allowing multiple opportunities for simultaneous prayer, thereby increasing the chance of the departed to pass from Purgatory and enter Heaven. In 1301, Cardinal Le Momier widened the Bull to “all desecration of the human body,” including cremation, but this was nothing more than a commentary and had no legal status. An anatomist at the time of Mundinus comments that as a result of the Bull, dissection of humans should not be practiced because of the revulsion that it would cause. Nevertheless, Mundinus pressed on with his dissections just a few years later.

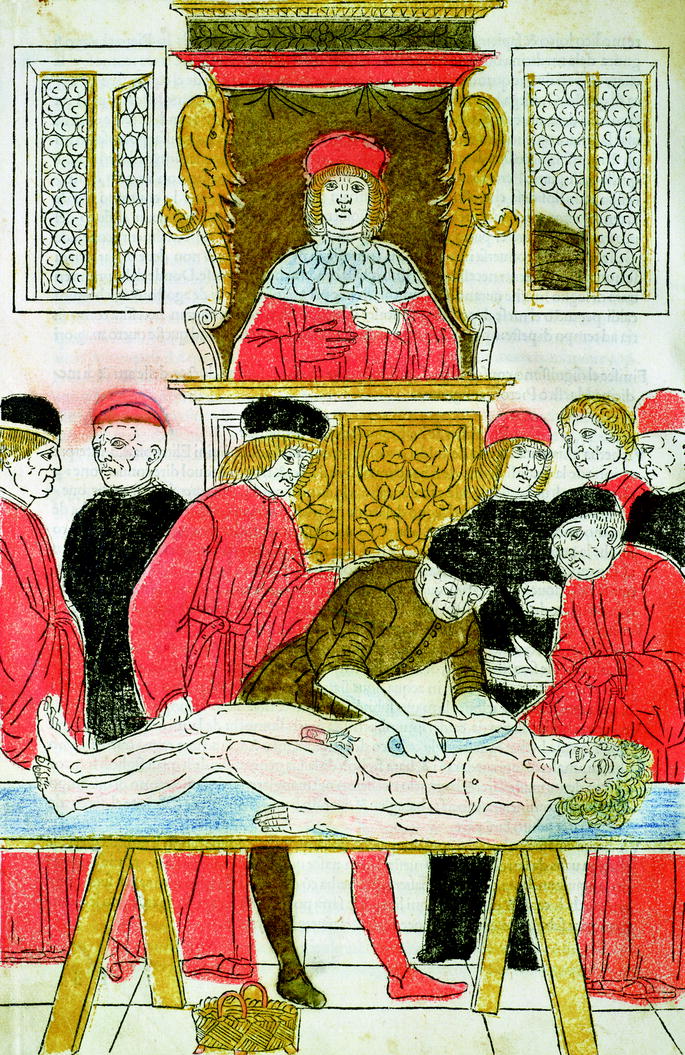

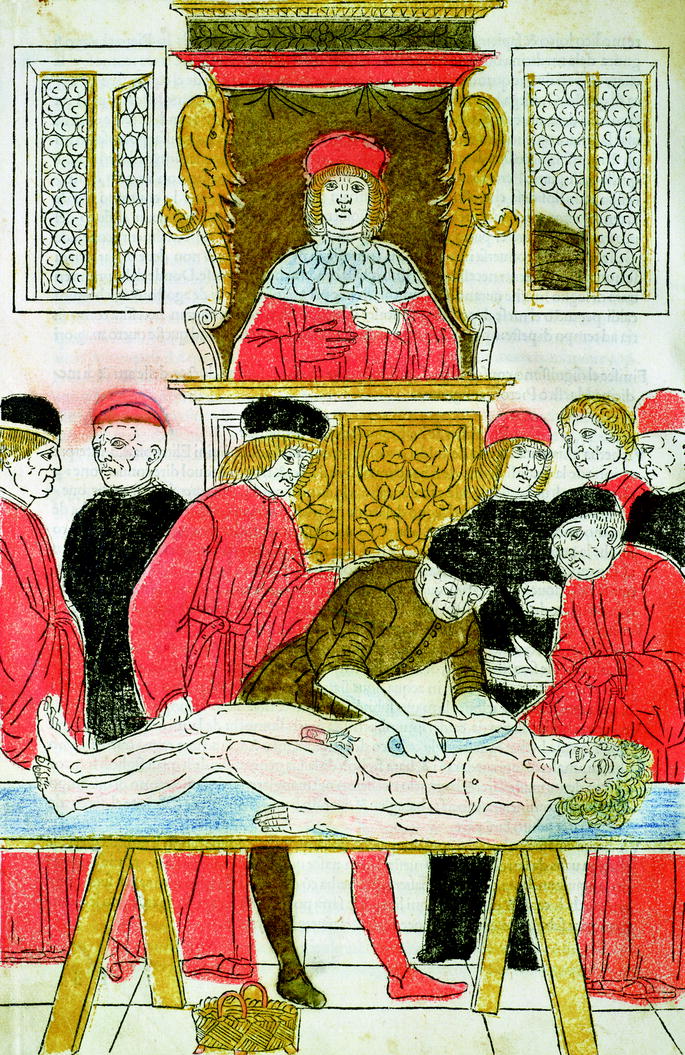

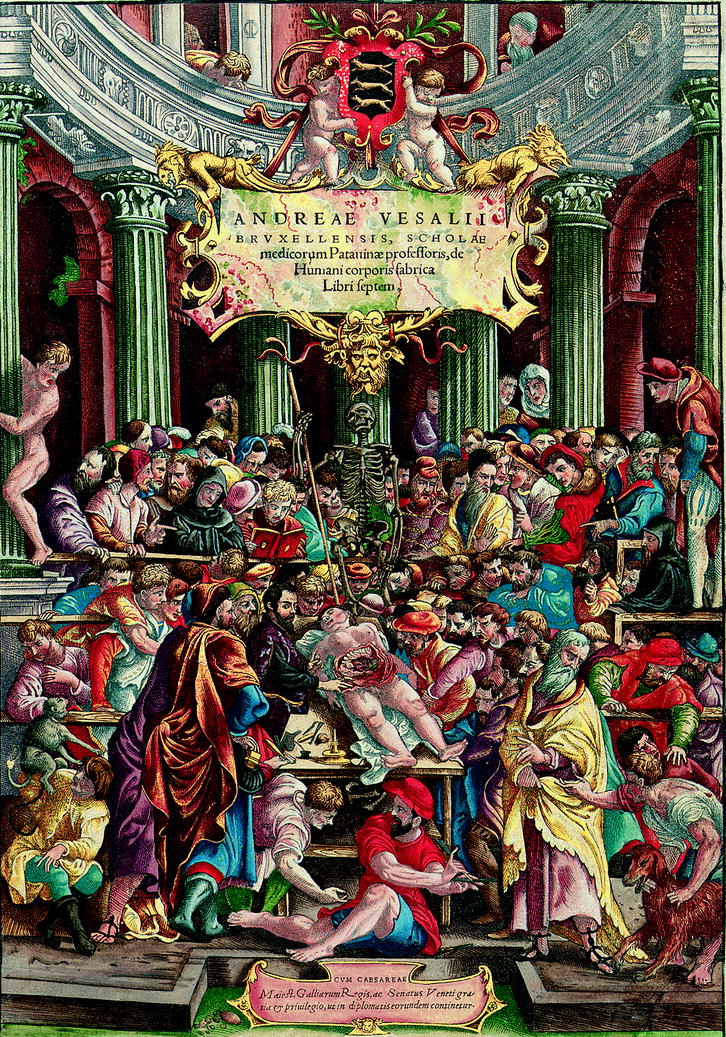

As Latin translations of the Arabic versions of Galenic texts became more available in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, factual verification of anatomical dissection was deemed necessary by the reading of the accepted texts. It was this “reading” by the Professor and the “demonstrating” of anatomy revealed by the “Prosector” that was the method of anatomical education in the time of Leonardo. This relationship is clearly depicted in “La lezione di anatomia” in the Fasciculus Medicinae of Johannes de’ Ketham (Fig. 2.2).

Fig. 2.2

Johannes de’ Ketham, The Dissection. ALG 178332. Illustration from Fasciculus Medicinae by Johannes de’ Ketham (d.c.1490) 1493 (woodcut), Italian School (fifteenth century)/Biblioteca Civica, Padua, Italy/Alinari/The Bridgeman Art Library

Despite Berengario’s words urging the anatomist to learn from his own experience, the same presentational relationship between Reader, Prosector, and Demonstrator is revealed in the frontispiece to his text Isagoge Breves.

It is from this teaching method that Vesalius really broke with tradition. In the frontispiece to his book de Fabrica Humana Corporis, he illustrates himself at the side of the corpse, personally carrying out the dissection and the demonstration of the parts. He has his quill pen and paper at his side to allow faithful recording of his findings as the dissection proceeds (Fig. 2.3). Here the paradigm has shifted very significantly: the Professor, or Reader, has become Prosector, Demonstrator, and Recorder, revealing the investigational approach to anatomy that put Vesalius apart from all of those between himself and Galen.

Fig. 2.3

Frontispiece of de Fabrica. CH 466697. Frontispiece to De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem by Andreas Vesalius (1514–64), published by Johannes Oporinus, Basel, June 1543 (colour woodcut) (see also 233019), Venetian School, (sixteenth century)/Private Collection/Photo © Christie’s Images/The Bridgeman Art Library

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree