Fig. 7.1

Schematic of the principles of Left ventricular reconstruction (As proposed by Dor in 1985)

Despite all this intuitive work on preserving left ventricular geometry, there was little interest in adopting these techniques into widespread clinical practice.

The 1980s were marked by two important steps in the knowledge of evolution and prevalence of ischemic failing ventricles:

1.

The mechanism of progressive ventricular dilatation following transmural myocardial infarction, also known as remodeling, was well analysed and characterized [8]. The role of neurohormonal activation was established and this helped to provide therapeutic targets [9]. Ischemic remodelling lead to progressive ventricular dilatation which then sets in motion the cascade of heart failure [10].

2.

Aggressive treatment of acute myocardial infarction, by revascularization of the occluded artery, has resulted in improved the survival rates. However, even after successful recanalization, the left ventricular wall of survivors, remains affected by scar in 80–100 % of cases; the infarct size varying from 6 to 60 % of the ventricular surface area as indicated by Christian [11].

Various imaging modalities such as cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) developed as accurate, reliable and reproducible tools [12] to assess both anatomy and performance of the ventricles after infarction. Use of contrast MRI further enhanced the utility of this imaging modality [13].

More recently, three dimensional echocardiography and volume rendered images with multi-detector CT scanning have shown particular promise in this arena.

Fate of the Left Ventricle after Infarction

Gorlin in 1967 observed that:

when 20 % to 25 % of LV area is asynergic, contraction of the myofibers to maintain stroke volume exceeds pathophysiological limits and cardiac enlargement (by the Frank-Starling mechanism) must ensue to maintain cardiac output.

There are two types of asynergy seen as consequence of ventricular aneurysms: regional akinesis (total lack of wall motion), and regional dyskinesis (paradoxical systolic expansive wall motion.

In spite of revascularization of the culprit artery altering the immediate prognosis, the left ventricular wall may remain diseased [14].

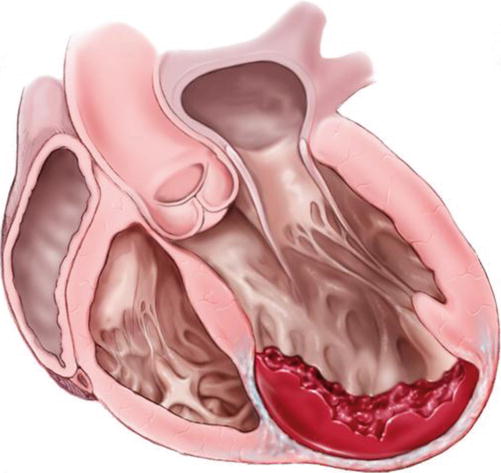

(A)

Evolution of the Infarcted Area: The infarcted wall undergoes changes that start with necrosis, progress to fibrosis and, eventually to calcification

1.

The typical left ventricular aneurysm is characterized by a transmural infarct (Fig. 7.2).

Fig. 7.2

Anteroseptal infarcts with extensive apical and septal involvement (a), Anterior infarct with predominantly septal involvement (b). Note adjacent mural thrombus formation

2.

The use of thrombolysis and/or revascularization in the acute phase may prevent transmural necrosis (Fig. 7.2b). Ventricular muscle adjacent to the epicardial artery is salvaged by recanalization, but the subendocardial muscle is necrotic, as described by Bogaert in 1997 [14]. The resultant ventricular wall may have viable myocardium which maybe evident at surgery (or during Thallium test) surrounding an akinetic, necrotic zone. The scarred asynergic ventricular wall may result in dyskinesia or akinesia. In both morphologies, it is important to know the extent of ventricular wall is abnormal, since this determines the indications and prognosis of surgical intervention.

3.

Location: The antero–apical and septal regions are most commonly involved in anterior infarctions caused by left anterior descending artery occlusion. Involvement of the septum is difficult to assess on ventriculography. The septum is best assessed by biplane angiography, echocardiography or cardiac MRI.

4.

The extent of asynery or abnormality governs the prognosis of the left ventricle after infartion. This can be assessed by a variety of imaging techniques. Traditionally angiography using the centerline method in the right oblique projection has been used. However, increasingly, other techniques such as contrast echocardiography, radionuclide ventriculography, multi-slice CT Scan, cardiac magnetic resonance (MRI), provide more information. Analysing the LV wall and the presence of a necrotic scar is very important. The extent of asynergy can be expressed as the ratio between the length of necrotic wall and the total length of the LV circumference. The progression towards severe heart failure is likely when this ratio reaches 50 %.

(B)

Fate of the Non-Infarcted Myocardium:

While normal at first, the undamaged myocardium undergoes hypertrophy to compensate for the lack of contractility of the necrotic wall, and finally dilates by a combination of mechanical forces and neurohormonal signaling. The Frank-Starling mechanism explains the early dilatation that temporarily improves the cardiac output and function. LaPlace’s Law described increased wall stress and this is the fundamental reason behind the deleterious effects on myocardial contractility due to increased wall tension. Left ventricular remodeling is the term used to describe the progressive dilatation of the heart, and is based on a set of complex inflammatory and neurohormonal processes. Gaudron suggested that the culmination of this process is progressive dilatation of the non-infarcted area with an ensuing spherical shape and akinesia, which occurs, in 20 % of patients treated for myocardial infarction [15].

Harvey White was an early proponent of using left ventricular volume as a sensitive marker of post-infarction ventricular dysfunction [16]. Yamaguchi used left ventricular end-systolic volume as an important predictor for prognosis after surgical repair [17]. Doubling of indices can be considered markers of severe dilatation (normal values are 25–30 ml/m2 for end-systolic volume index (ESVI) and 50/60 ml/m2 for end-diastolic volume index (EDVI).

Who Should Be Considered for Surgical Ventricular Restoration (SVR) or Left Ventricular Reconstruction (LVR)?

Currently SVR is largely established for patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy after myocardial infarction, although some have advocated a variant of the technique for patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy.

Presently, the “ideal” patient should have a dilated ventricle and NYHA class III to IV heart failure symptoms following infarction. As for patients with LV aneurysms, totally asymptomatic patients should not be considered. The SVR/LVR is advocated for patients with a prior left anterior descending artery territory infarct (anterior wall, septum region). Patients with both LAD and circumflex artery occlusions may not be suitable candidates. The infarcted segment can either be akinetic or dyskinetic.

The timing of surgery is also important. Conventional wisdom states that 6 weeks following infarction should elapse before SVR is considered. There is, however, one small series of seven patients that underwent surgery soon after a large anterior infarction with encouraging results [18]. Anecdoctal cases have been performed in the early post-infaction period (2–14 days), particularly in the setting of low cardiac output as salvage therapy.

Preparation for Surgery

1.

Pre–operative preparation: Patients that have been inpatients in cardiology for recurrent episodes of CHF and titration of medical therapy, often need tuning up. A variety of tests may be of benefit:

Measurement of pulmonary arterial pressure (PAP) by right heart catheterisation and the response to vasodilator therapy, and/or oxygen administration helps in stratifying patients.

Detailed echocardiographic assessment including three-dimensional echocardiography is of great benefit. Mitral regurgitation has to be assessed by pre-operative echocardiography or trans-esophageal echocardiography if necessary.

The extent of the scar and its location are important in planning the operation. Establishing viability of the remote non-infarcted segments is crucial because often there are regional wall motion abnormalities in these areas. Gadolinium enhanced magnetic resonance imaging is a good test of viability. Segments that are hypokinetic predictably improve if there is no hyperenhancement. If MRA is contraindicated due to implantation of a defibrillator or pacemaker, multi slice CT scan or 3-D echocardiography may be used. However, these tests may only assess contractility of the remote segments.

A coronary angiogram is mandatory to delineate the coronary anatomy.

2.

Preoperative medical treatment is continued except for cessation of anti-platelet and anticoagulant therapy.

The intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) should be used whenever there is hemodynamic compromise, such as evolving infarction without remission, CHF not improved by medical therapy, patients with a mechanical complication of myocardial infarction, or incipient renal failure. Some have found it useful in all SVR procedures as adjuvant therapy.

3.

Specific operative procedures: A femoral arterial line is inserted for monitoring purposes and to allow quick access for insertion of a balloon pump if required. The patient is prepared for saphenous vein harvest if required. Cannulation for cardiopulmonary bypass is routine, utilizing an aortic cannula and a dual stage right atrial cannula. Monitoring includes arterial line, central venous pressure and Swan Ganz catheter. Trans-esophageal echocardiography is used routinely.

For the management of cardiopulmonary bypass, we minimize crystalloid use. Retrograde autologous priming of the circuit helps remove the crystalloid that is added to prime the circuit. Hemofiltration during bypass in helpful in reducing myocardial edema.

Left ventricular reconstruction (LVR): (Fig. 7.3)

Fig. 7.3

Steps of surgery for Left Ventricular Reconstruction (LVR): Left Ventricular Reconstruction: (a) The antero septo apical aneurysm with mural thrombi: the dilatation also affects the non-scarred myocardium on septum (S) and lateral wall (L). (b) Intra-operative photograph showing dimpling of Left ventricular scar with use of vent. (c) Coronary revascularization accomplished first on arrested heart. (d) The continuous purse-string suture at the limit between fibrous and normal myocardium (Fontan “Trick”). (e) possible endocardectomy if needed. (f) The suture is tied on a rubber balloon inflated to 50 mm per square meter of the body surface area (normal diastolic volume). The shortening of the SL length illustrates the reorganization of the curvature. (g) The Dacron patch anchored on the suture. The right ventricle apex projects beyond the new LV apex

Sequence of surgical steps may depend on the acuity of the patient, the extent of ischemia, presence or absence of left ventricular thrombus, etc.

1.

The repair may be conducted utilizing the open-beating or cardioplegic arrest methods of myocardial protection (Fig. 7.4).

Fig. 7.4

Completed patch implant

2.

Grafting all coronary arteries with meticulous myocardial protective strategies is important. Retrograde cardioplegia preserves septal contractility as is crucial in preventing low output states postoperatively. Particular care is taken to revascularize the LAD, or diagonal if possible, thereby increasing septal blood flow.

What is the best resultant shape/volume of the operated left ventricle? What sort of patch should be used? These are interesting questions that are yet to be resolved conclusively. Although some authors have suggested that the LV can be “tailored” without a patch, this can be difficult, especially for the novice surgeon. This technique promoted by McCarthy is described in the next chapter. The size of the patch and the stiffness of the patch also may have a bearing on the outcome long-term, and these matters are addressed in the next chapter.

Management of Associated Mitral Regurgitation

Mitral regurgitation is found often in these patients, either due to the nature of the remodeling or due to involvement of the infero-basal wall of the left ventricle. Our personal preference to correct any degree of mitral regurgitation that is greater than moderate or 2+. Typically, this is done by utilizing a flexible posterior band or a remodeling annuloplasty ring. At times a simple Alferi stitch maybe resorted to as well. The mitral valve can be accessed and repaired through the ventriculotomy or via a separate incision in the left atrium or a trans-septal approach. The limitation of the ventricular approach is that access to the valve may be suitable only in very large scars that are more apico-septal in orientation (Fig. 7.5).

Fig. 7.5

Completed mitral valve repair. Note vein graft to inferior to a branch of the RCA and trans-septal approach to mitral valve

1.

The LVR technique: Dor reported the technique of endo-ventricular patch patch plasty in 1989 [19]. In this classic technique, the ventricular wall is opened at the center of the scarred area, which often appears as a dimpled area once a left ventricular vent is placed after aortic cross clamping (Fig. 7.3b). Any clots present are removed. It is important to note that some fragmented and friable small clots may not be seen on trans-esophageal or epicardial echocardiography, especially if the thrombus is non-homogenous or small. The endocardial scar is dissected and resected if the scar is calcified (Fig. 7.3e) or if there is evidence of ventricular tachycardia (VT). Ablative treatment at the edge of scar usually at the borderzone, with radio-frequency energy or cyoablation is a short adjunctive procedure shown to limit postoperative dysrrhythmias.

The reconstruction of the left ventricular cavity is started using a continuous suture 2-0 monofilament purse-string suture (Fig. 7.3d) with bites going into the muscle at the borderzone (the junction between the scar and normal myocardium). Typically, this suture is run as a continuous purse-string suture is tightened over a rubber balloon inflated within the cavity at the theoretical diastolic left ventricular volume (50–60 ml per sq.m. of BSA). This technique was introduced to avoid making the residual cavity too small [20]. This is a good guide to surgeons with limited experience. The endoventricular circular suture is also known as the “Fontan stitch” (Fig. 7.3d) and helps optimize orientation of the patch while selecting its shape and size.

The septum and apex are more involved than the lateral wall in the antero-septo-apical type of scarring. In these cases, the suture, thus placed deeply in the septum, totally excludes the apex and the posterior wall below the base of the posterior papillary muscle, and only a small portion of lateral wall above the base of the antero-lateral papillary muscle. Therefore, the orientation of this new neck (and of the patch) roughly follows the axis of the septum.

Dor described the use of a Dacron patch that is sutured to the Fontan Stitch. The excluded, redundant bits of scar are then sutured over the patch to aide in hemostasis. The traditional Dacron patch is quite stiff, and various modifications of the technique include use of Gortex, bovine pericardium or no patch at all.

2.

Wean off CPB: Typically, weaning from bypass is slow and gentle to allow complete recovery of both ventricles. Frequent use of antegrade and retrograde blood cardioplegia every 8–10 min helps preserve biventricular function and allows quicker recovery of the heart. Our choice of inotrope typically involves milrinone and dobutamine. Often, norepinephrine and/or vasopressin are required as an adjunct to counter the hypotension that is seen due to the effect of milrinone. Liberal use of the balloon pump has been found to be very useful. Prophylactic atrial and ventricular pacing wires are used to ensure a regular rhythm. If there is a history of atrial fibrillation or ventricular arrhythmia, prophylactic use of amiodarone helps reduce the risk of lethal arrhythmias.

3.

Specific modifications: (Fig. 7.6)

(a)

Changes based on alterations of the ventricular wall

Autologous tissue has been used for the patch: either a semicircle of the fibrous endocardial scar mobilized with a septal hinge if this scar is strong, or autologous pericardium.

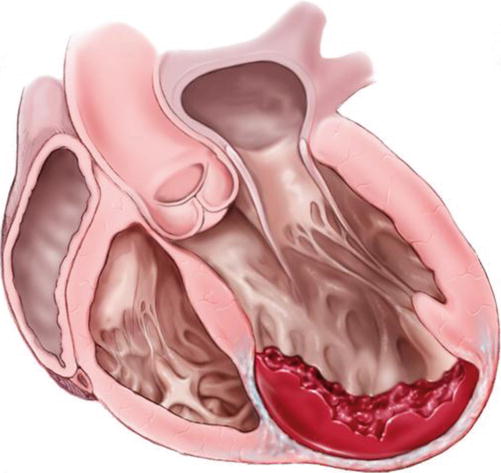

Fig. 7.6

This shows the left ventricle in longitudinal section with mural thrombus along the septum and antero-apical wall

Figure 7.7a, b show a septal hinge being used to patch the defect.

Fig. 7.7

Particular cases of Endoventricular patch reconstruction: (a) utilization of the septal scar as an autologous patch. A semicircular portion of the scar mobilized from the septum with a septal hinge is sutured on contractile muscle inside the left ventricle. (b) Septal Involvement after opening up the left ventricular scar. (c) Operative photograph of septal infarct and scar. (d) Septal Involvement. The patch is anchored above the septal repair, which is excluded from the left ventricular cavity

When the tissues are soft and necrotic, during the repair of an acute mechanical complication of myocardial infarction (exclusion of septal rupture or treatment of free wall fissures), the patch has to be inserted into healthy tissue by deep stitches reinforced with Teflon pledgets. The patch is anchored above the septal rupture which is excluded from the LV cavity (Fig. 7.7d).

Figure 7.7c, d show a septal infarct that has been excluded with a pledgetted plicating suture and subsequent implantation of a patch to exclude the septal infarct.

(b)

Amount of Scar Exclusion: In cases of a large amount of asynergy (above 50 % of LV cavity) surgery is accomplished with some modifications. These patients typically are in Class III or IV heart failure and on inotropes. Mean pulmonary artery pressure is often above 25 mmHg, ejection fraction (EF) below 30 %, EDVI above 150 ml/m2, and ESVI above 60 ml/m2. Ventricular tachycardia may be present in nearly 50 % of cases and this should preferably be addressed by ablative strategies and/or endocardectomy. Mitral insufficiency has to be repaired in the majority of cases. Mitral valve repair in this instance is performed as a remodelling annuloplasty, with Bolling and his followers advocating rigid, shaped rings. David and his group have shown good results with flexible posterior bands. If the presentation is acute or if there is difficulty in repairing the valve, a valve replacement with chordal preservation should be considered. Theoretically, the exclusion of all scarred areas may lead to a very small LV cavity with a high risk of immediate or delayed diastolic dysfunction. The Fontan stitch is placed slightly beyond the edge of healthy muscle at the transitional area. The use of a mandril or balloon inside the LV, inflated at the theoretical diastolic volume of the patient is a useful guide to optimize tension on the suture. The patch can be slightly more redundant (3–4 cm in diameter) than in the usual technique.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree