Laparoscopic Partial Fundoplication for Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease

Marco E. Allaix

Marco G. Patti

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Several conditions, including irritable bowel syndrome, achalasia, gallbladder disease, coronary artery disease, or psychiatric disorders can present with heartburn as the main symptom.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Heartburn, regurgitation, and dysphagia are considered typical symptoms of GERD.

GERD can also cause atypical symptoms such as cough, wheezing, chest pain, hoarseness, and dental erosions.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Clinical history, based on symptoms only, has a low diagnostic accuracy of GERD in about 30% of patients.3

Upper endoscopy is often the first test performed to confirm the diagnosis of GERD. However, about 50% of patients with clinical symptoms of GERD do not have endoscopic sign of esophagitis.3 In addition, endoscopic evaluation is highly operator dependent, especially in the assessment of low-grade esophagitis.4 Therefore, the major role of endoscopy is to detect Barrett’s esophagus (usually present in 1% to 5% of patients with GERD) and to exclude gastric and duodenal pathology.

Barium swallow is useful for detecting and characterizing the type and size of a hiatal hernia; for determining the location and size of a stricture; and for evaluating length, diameter, and function of the esophagus. This test, however, is not diagnostic of GERD as a hiatal hernia or reflux of barium can be present in the absence of abnormal reflux or absent in the presence of clinically significant GERD.

Esophageal manometry provides information about the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) in terms of resting pressure, length, and relaxation and the amplitude and propagation of esophageal peristaltic waves. In addition, manometry is essential for proper placement of the pH probe for ambulatory pH monitoring (5 cm above the upper border of the LES).

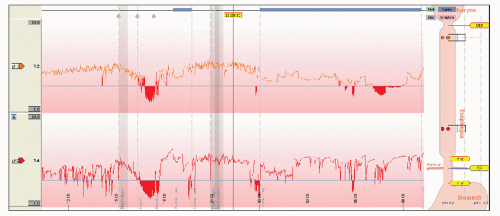

24-hour ambulatory pH monitoring is considered the gold standard for the diagnosis of GERD (FIG 1). Its role is key in the workup as it determines the presence and amount of abnormal reflux and it establishes a temporal correlation between symptoms and episodes of reflux (particularly important when cough or chest pain are present).5 An abnormal score not only confirms the diagnosis but also is an independent predictor for the successful outcome of antireflux surgery.6 Finally, pH monitoring is mandatory for the proper evaluation of patients who have recurrent symptoms after antireflux surgery.7

Combined multichannel intraluminal impedance and pH testing (MII-pH) detects episodes of reflux, regardless of the pH of the refluxate, by identifying changes inducted by the presence of liquids and gas in the esophagus. The episodes are classified as acid, weakly acid, or nonacid on the basis of concomitant pH monitoring. This test is useful in identifying bile reflux and does not require cessation of proton pump inhibitors for testing.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

A laparoscopic fundoplication is currently considered the procedure of choice for the treatment of GERD.

Even though several eponyms are used to describe different antireflux procedures, we believe that it is more important to focus on the technical elements that make a fundoplication effective and long lasting.

The type of fundoplication (total vs. partial) is tailored to the quality of esophageal peristalsis as documented by the preoperative manometry. In the United States, a partial fundoplication is proposed only to patients with very impaired or absent esophageal peristalsis in order to reduce the risk of postoperative dysphagia (FIG 2).

Preoperative Planning

A careful symptomatic evaluation testing is performed in every patient before surgical intervention.

Positioning

After induction of general endotracheal anesthesia, the patient is positioned in low lithotomy position with the lower extremities extended on stirrups with knees flexed 20 to 30 degrees. Alternatively, a split-leg table may be used.

To avoid sliding as a consequence of the steep reverse Trendelenburg position used during the entire procedure, a beanbag is inflated to create a “saddle” under the perineum.

Because increased abdominal pressure from pneumoperitoneum and the steep reverse Trendelenburg position decrease venous return, pneumatic compression stockings are always used as prophylaxis against deep venous thrombosis.

An orogastric tube is placed to keep the stomach decompressed during the procedure.

A Foley catheter is inserted at the beginning of the operation and removed at the end.

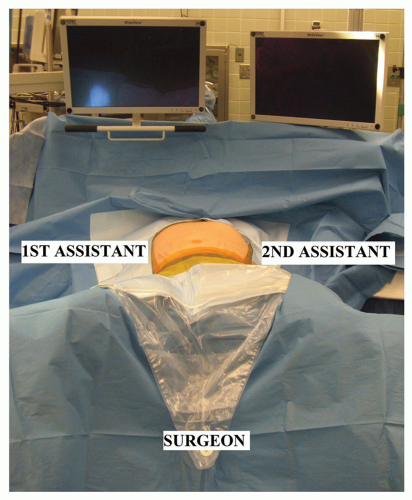

The surgeon stands between the patient’s legs. The first and second assistants stand on the right and left side of operative table (FIG 3).

PLACEMENT OF PORTS

Five 10-mm trocars are used for the procedure (FIG 4).

The first incision is made in the midline 14 cm distal to the xiphoid process and a Veress needle is introduced into the peritoneal cavity. The peritoneal cavity is initially insufflated to a pressure of 15 mmHg. Subsequently, under direct vision, an optical port with a 0-degree scope (port 1) is placed. Once this port is placed, the 0-degree scope is replaced with a 30-degree scope and the other trocars are inserted under laparoscopic vision.

Port 2 is placed in the left midclavicular line at the same level of port 1. It is used by the assistant for

traction on the gastroesophageal junction and to take down the short gastric vessels.

Port 3 is placed in the right midclavicular line at the same level of the other two ports. A retractor is used through this port to lift the left lateral segment of the liver to expose the gastroesophageal junction. The retractor is held in place by a self-retaining system fixed to the operating table.

Ports 4 and 5 are placed under the right and left costal margins so that their axes and the camera form an angle of about 120 degrees. These ports are used by the operating surgeon for the insertion of graspers, scissors, and dissecting and suturing instruments.

The instrumentation necessary for laparoscopic partial fundoplication is reported in Table 1.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree